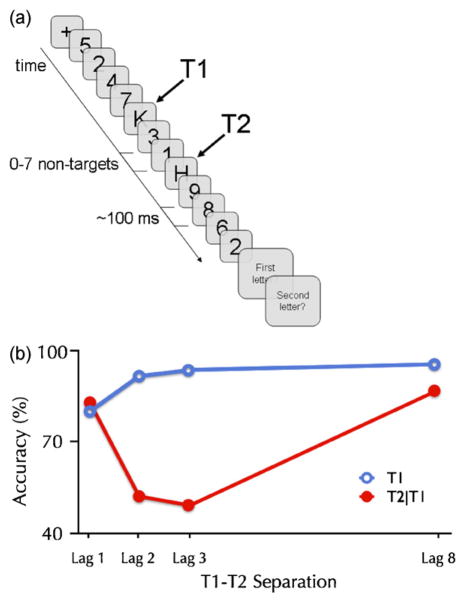

Fig. 1. The basic attentional-blink paradigm.

(a) The attentional-blink paradigm as it is most commonly used originates from a classic paper by Chun and Potter (1995). As shown in panel A, a rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP) stream of digits (the non-targets or distractors) is sequentially presented in the middle of the screen, typically at a rate of about 10 items/second. Subjects are instructed to identify two unspecified letters (the targets, referred to as T1 and T2, respectively) embedded within the stream. The paradigm requires subjects to give their responses after presentation of the stream, at their own pace, so that additional interference effects arising from speeded responses are avoided. The primary measure of interest is the percentage of correct T2 reports from trials in which T1 was accurately identified (T2|T1), thereby ensuring that T2s are not missed due to a coincidental lapse of attention. When subjects are instructed to ignore the T1 stimulus, T2 is usually reported accurately regardless of the lag between the two targets (Raymond et al., 1992). This suggests that the AB is the result of attending to T1 and consolidating it into working memory (Chun and Potter, 1995), rather than a perceptual deficit.

(b) Subjects often fail to report T2 when it is presented within 200–500 ms after T1, whereas when the interval is longer, both targets are usually reported in the order in which they were presented. Importantly, when T1 and T2 are presented within about 100 ms SOA, subjects quite often report both targets. This paradoxical finding, referred to as lag-1 sparing (Potter et al., 2002) and discussed later in this paper, has proven to be quite an important aspect of the AB.