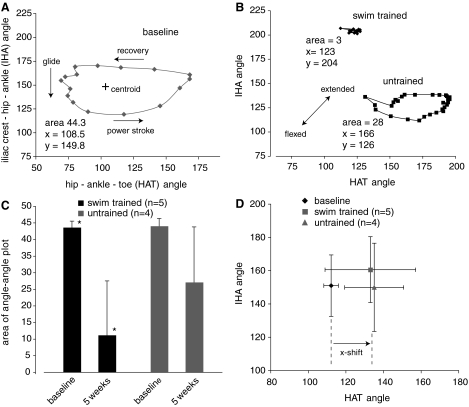

FIG. 3.

(A) The angle-angle plot from a single normal swimming stroke is shown as an example. The iliac crest–hip–ankle (IHA) angle is plotted against the hip–ankle–toe (HAT) angle, with each point representing one frame of a digital video made at 60 Hz. The main power stroke involves the extension first of the HAT (x-axis), followed by extension of the IHA angle (y-axis). This is followed by a recovery stroke involving HAT flexion and period of glide with the limb flexed (glide). (B) Single strokes from a swim-trained and an untrained animal, at 5 weeks post-injury, are shown to illustrate the extremes of limb position and activity for this study. The angle-angle plot areas and centroids are shown. (C) The mean angle-angle plot areas for the trained and untrained groups are shown. The mean area for the swim-trained group was found to be significantly smaller at 5 weeks post-injury as compared to baseline (mean ± SD, p < 0.05). The mean areas for the untrained animals were found to be not different from baseline (mean ± SD). (D) The mean centroids for the angle-angle plots from both trained and untrained groups were shifted on the x-axis, indicating an overall more extended limb position that was not positively influenced by acute swim training with supplementary cutaneous feedback (mean ± SD).