Abstract

During Drosophila melanogaster oogenesis, a germline stem cell divides forming a cyst of 16 interconnected cells. One cell enters the oogenic pathway and the remaining 15 differentiate as nurse cells. Although directed transport and localization of oocyte differentiation factors within the single cell are indispensible for selection, maintenance, and differentiation of the oocyte, the mechanisms regulating these events are poorly understood. Mago Nashi and Tsunagi/Y14, core components of the exon junction complex (a multiprotein complex assembled on spliced RNAs), are essential for restricting oocyte fate to a single cell and for localization of oskar mRNA. Here we provide evidence that Mago Nashi and Tsunagi/Y14 form an oogenic complex with Ranshi, a protein with a zinc finger-associated domain and zinc finger domains. Genetic analyses of ranshi reveal that (1) 16-cell cysts are formed, (2) two cells retain synaptonemal complexes, (3) all cells have endoreplicated DNA (as observed in nurse cells), and (4) oocyte-specific cytoplasmic markers accumulate and persist within a single cell but are not localized within the posterior pole of the presumptive oocyte. Our results indicate that Ranshi interacts with the exon junction complex to localize components essential for oocyte differentiation within the posterior pole of the presumptive oocyte.

Keywords: Drosophila, oogenesis, exon junction complex, Mago Nashi, Tsunagi/Y14, localization

Introduction

In organisms as diverse as insects, frogs, and mammals, female germ cells develop and differentiate as clusters or cysts of clonally derived interconnected cells (Büning, 1994; de Cuevas et al., 1997; Pepling et al., 1999). Typically, primordial germ cells migrate from their site of origin to the developing gonad (Eddy, 1975; Extavour and Akam, 2003; Nieuwkoop and Sutasurya, 1979, 1981). Within the gonad, primordial germ cells form germline precursor cells known as cystoblasts. Cystoblasts undergo synchronous division with incomplete cytokinesis, resulting in cysts consisting of 2n cells (cystocytes) interconnected by intercellular bridges, called ring canals (Büning, 1994; de Cuevas et al., 1997; Pepling et al., 1999). For example, in Xenopus laevis and Drosophila melanogaster, cystoblasts divide four times to form 16-cell cysts (Gard et al., 1995; Klymkowsky and Karnovsky, 1994). Upon completion of the mitotic divisions, cystocytes enter meiosis synchronously and undergo processes that transform one or more cystocytes into an oocyte. In X. laevis, all 16 cystocytes differentiate as oocytes (al-Mukhtar and Webb, 1971; Coggins, 1973). While in D. melanogaster, 15 cystocytes form the nurse cells (polyploid germline cells that support the growth and differentiation of the oocyte) and one cystocyte differentiates as an oocyte (King, 1970; Spradling, 1993). How a single cell, the oocyte, is selected from a cyst of 16 cells all sharing a common cytoplasm is an intriguing and important problem in developmental biology.

Oocyte selection in D. melanogaster occurs in the anterior tip of the ovary, in a region designated as the germarium (King, 1970; Spradling, 1993). Within the anterior tip of the germarium, a germline stem cell (GSC) divides, producing a replacement GSC and a cystoblast (Wong et al., 2005). GSCs and cystoblasts both have a spherical cytoplasmic membranous structure, the spectrosome (Deng and Lin, 1997; Lin et al., 1994). In subsequent cystoblast and cystocyte divisions, spectrosomes become branched structures (fusomes) extending through the ring canals into each cell of the cyst. Fusome material is partitioned unequally at each cyst-forming division, resulting in a 16-cell cyst with two cells (pro-oocytes) containing more fusome material than the other cells (de Cuevas and Spradling, 1998). One of the two pro-oocytes differentiates as the oocyte, while the other pro-oocyte and cells within the cyst become nurse cells. The fusomes consist of membrane skeletal proteins (e.g., Adducin-like protein, Ankyrin, α-Spectrin and β-Spectrin) and are associated with microtubule motors (e.g., Dynein heavy chain 64C and Klp61F), microtubule-associated proteins (e.g., Deadlock, Lis1, Orbit/Mast and Spectraplakin) and other fusome-interacting proteins (de Cuevas et al., 1996; Lin et al., 1994; Liu et al., 1999; Máthé et al., 2003; McGrail and Hays, 1997; Petrella et al., 2007; Röper and Brown, 2004; Wehr et al., 2006; Wilson, 1999; Yue and Spradling, 1992). Mutations in genes encoding fusome components (e.g., α-Spectrin and hts; encoding the Adducin-like protein) disrupt fusome formation, producing cysts with abnormal numbers of cystocytes and lacking an oocyte (de Cuevas et al., 1996; Lin et al., 1994). Proteins and RNAs required for oocyte differentiation are transferred from the pro-nurse cells to the two pro-oocytes and ultimately accumulate, in association with the fusome, in one of the two pro-oocytes, the presumptive oocyte (Huynh and St Johnston, 2004). Microtubule depolymerizing drugs and mutations in genes encoding fusome-associated microtubule motors (e.g., Dynein heavy chain 64C; Dhc64C) disrupt fusome formation and the selective accumulation of proteins and RNAs within the two pro-oocytes and the presumptive oocyte, generating cysts without an oocyte (Bolivar et al., 2001; Huynh and St Johnston, 2000; Theurkauf et al., 1993). Considered together, the results from microtubule inhibitor studies and the genetic analyses of genes encoding microtubule motors or microtubule-associated proteins indicate that the fusome and fusome-associated proteins are essential for establishing a polarized microtubule network necessary for the directional transport of components from the pro-nurse cells to the pro-oocytes and eventually to a single pro-oocyte, resulting in oocyte selection and differentiation (Huynh and St Johnston, 2004).

Genetic and molecular analyses of Drosophila oogenesis reveal that progression of oocyte differentiation can be divided into at least four discrete steps. The first identifiable step in oocyte differentiation is the formation of the synaptonemal complex (SC) within the nuclei of the two pro-oocytes (germarial region 2a; R2a) (Carpenter, 1975; Huynh and St Johnston, 2000; King, 1970). During cyst maturation, SCs are next observed within four adjacent cells and, in anterior germarial region 2b (R2b), SCs are restricted to the pro-oocytes, and finally to the presumptive oocyte (posterior R2b and germarial region 3; R3) (Huynh and St Johnston, 2000; Page and Hawley, 2001). The second identifiable step in oocyte differentiation is the directed transport of mRNAs, proteins and centrioles to the two pro-oocytes of cysts within posterior R2a (Bolivar et al., 2001; Cox and Spradling, 2003; Grieder et al., 2000; Huynh and St Johnston, 2004; Mahowald and Strassheim, 1970). Proteins required for oocyte differentiation, such as Bicaudal-D (BicD), Egalitarian (Egl) and the homologue of the Cytoplasmic Polyadenylation Element Binding protein (Orb), are detected within the cytoplasm of all cells within each cyst in anterior R2a. As SCs become restricted to the pro-oocytes (posterior R2a), BicD, Egl, and Orb selectively accumulate within the cytoplasm of the two pro-oocytes (Lantz et al., 1994; Mach and Lehmann, 1997; Schüpbach and Wieschaus, 1991; Suter et al., 1989; Suter and Steward, 1991). The third identifiable step in oocyte differentiation is the accumulation of BicD, Egl, Orb and centrioles within the cytoplasm of one of the two pro-oocytes (R2b), the presumptive oocyte. Initially, BicD, Egl, Orb and centrioles localize within the anterior pole of the presumptive oocyte and subsequently translocate to the posterior pole of the presumptive oocyte, defining the fourth step in oocyte differentiation (Bolivar et al., 2001; Cox and Spradling, 2003; Grieder et al., 2000; Lantz et al., 1994; Mach and Lehmann, 1997; Mahowald and Strassheim, 1970; Schüpbach and Wieschaus, 1991; Suter et al., 1989; Suter and Steward, 1991). Mutant cysts in which any of these steps are disrupted produce 16-cell cysts consisting of 16 nurse cells, indicating that the steps are required for establishing and/or maintaining oocyte fate.

In a previous study (Parma et al., 2007), we showed that in germline clones lacking Tsunagi/Y14 (Tsu/Y14) the restriction of oocyte fate to a single cell within 16-cell cysts is disrupted. Tsu/Y14:Mago Nashi (Mago) heterodimers are core components of the exon junction complex (EJC), a protein complex assembled on spliced mRNAs (Gehring et al., 2009; Le Hir and Andersen, 2008; Tange et al., 2004). A complex of Mago and Tsu/Y14 is also required during oogenesis to establish the major axes of the oocyte, embryo, and adult, as well as for localizing oskar (osk) mRNA within the posterior pole of the oocyte (Hachet and Ephrussi, 2001; Micklem et al., 1997; Mohr et al., 2001; Newmark et al., 1997). The localization of osk mRNA within the oocyte posterior pole is essential for abdominal segmentation and for determination of primordial germ cells (Ephrussi et al., 1991; Ephrussi and Lehmann, 1992). During oogenesis, Mago and Tsu/Y14 co-localize within the nuclei of germline and follicle cells. In the germarium, Mago and Tsu/Y14 also co-localize within the cytoplasm of germline cells in a pattern that is indistinguishable from BicD, Egl, and Orb, components necessary for oocyte differentiation (Parma et al., 2007). Germline clones generated by employing a reduced function allele of mago are similar phenotypically to tsu null germline clones. Together, the co-localization of Mago and Tsu/Y14 within the cytoplasm of germarial germline cells and the similarity of the germline clonal phenotype of a reduced function mago allele and the tsu null allele suggest that Mago and Tsu/Y14 function jointly to restrict oocyte fate to a single cell.

Employing a shotgun proteomics approach, we identified at least 54 proteins that repeatedly co-immunoprecipitate (co-IP) with Mago (Bennett and Boswell, unpublished). One of the proteins is encoded by CG9793 and we designated the encoded protein as Ranshi (Japanese for oocyte). Here we show that Ranshi co-IPs with Mago and Tsu/Y14 from ovarian extracts, indicating that the proteins form an oogenic complex. To gain an understanding of Ranshi’s role during oogenesis, we also characterized the phenotypes of ovaries derived from homozygous and hemizygous ranshi females. Our phenotypic analyses of ranshi mutant females reveal that in ovaries deficient for Ranshi, components required for oocyte differentiation accumulate within the presumptive oocyte but fail to localize within the posterior pole, indicating that Ranshi forms a complex with EJC components that influences the posterior pole localization/anchoring of oocyte differentiation factors.

Materials and methods

Fly stocks, culturing, immunolocalization and immunoprecipitation

Standard methods were used for all crosses and culturing. Oogenic stages are according to Spradling (1993). Lines utilized to study ranshi were described previously (Parma et al., 2007). The following additional lines were used: (1) w1118; pBac(RB)CG9793e00091 (ranshi1); (2) w1118; pBac(RB)CG9793f03361 (ranshi2); (3) w1118; pBac(WH)CG8159f01126a; (4) w1118; pBac(WH)CG9797f06033; (5) y w hsFlp12; ranshi1/TM3, pp Sb e; (6) y w hsFlp12; pBac(WH)CG8223f02790; (7) w1118; +/CyO, p[w+; hs-pBac]; ranshi1/TM3, pp Sb e; and (8) p[w+, ubi-nlsGFP] p[ry+, FRT]40A.

The antibodies employed to analyze the ranshi oogenic phenotypes are described in Parma et. al. (2007). Ovaries were dissected from females 0-1 day after eclosion. Immunoprecipitation and immunohistochemistry were performed as described in previous studies (Mohr et al., 2001; Parma et al., 2007). Immunoprecipitated proteins were prepared for mass spectrometry as described by Andersen et. al. (2003) and the samples were analyzed by the University of Colorado, Mass Spectrometry, Central Analytical Lab. To identify proteins, we utilized the Mascot program (Matrix Science Inc.) to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information and Flybase databases. Immunoblotting of co-immunoprecipitated proteins and genetic interaction studies were employed to verify proteins found by mass spectrometry.

Transgenes

We generated two genomic rescue constructs, p[w+, ranshi+] and p[w+, CG8159+, ranshi+]. The constructs were made by PCR amplification of genomic DNA, following the manufacturer’s instructions using Pfx50 Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). To facilitate cloning primers contained the restriction sites EcoRI and XhoI: FranshiXhoI 5′-CTCCTCGAGCTGAAAGCCGAGATGAAACAGG-3′, and RranshiEcoRI 5′-CTCGAATTCCCGCGGATGCCTTTACGATAGA-3′ and F8159-ranshi 5′-CCTCGAGAGCTGTGCGACAAGTCCTTT-3′ and R8159-ranshi 5′-TGCGGCCGCAGCCCATGGACAAAACTCTG-3′. The transgenes were verified by DNA sequencing (Agencourt Biosience). The purified plasmids were injected into Drosophila embryos (BestGene, Inc.). Independent lines on the X, 2nd, and 3rd chromosome were recovered and tested for rescue of the ranshi phenotype.

Antibody generation and purification

Anti-Ranshi antibodies (α-Ranshi) were generated employing two unique peptides (amino acid residues 82-107, DEDFLRICQESPKSVLEQEELELDLA, and amino acid residues 137-162, SKINEDEPNNEDDIDYSEMDYLIYE). Oligonucleotides (for amino acid residues 82-107: 5′-AATTCgatgaagacttccttagaatctgccaggaatctcccaaaagtgtccttgagcaggaggagttggaactggatctggcatgaGG-3′ and 5′-TCGACCtcatgccagatccagttccaactcctcctgctcaaggacacttttgggagattcctggcagattctaaggaagtcttcatcG-3′; and for 137-162: 5′-AATTCtctaaaatcaacgaagacgagcccaataatgaggacgatattgattatagtgaaatggattaccttatttacgaaGG-3′ and 5′-TCGACCttcgtaaataaggtaatccatttcactataatcaatatcgtcctcattattgggctcgtcttcgttgattttagaG-3′) were synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc.) with terminal EcoRI and SalI restriction sites and used to amplify genomic DNA. The products were cloned into pMal-c2 (New England Biolabs) and pGEX 6p1 (GE Health) and correct inserts were verified by DNA sequencing (Agencourt Bioscience). The peptides were expressed in bacteria as maltose-binding protein (MBP)-Ranshi and glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-Ranshi fusion proteins. The resulting fusion proteins, GST-Ranshi (GST-Ranshi82 and GST-Ranshi137) and MBP-Ranshi (MBP-Ranshi82 and MBP-Ranshi137), were purified and characterized as described in Mohr et. al. (2001). Polyclonal antibodies against bacterially expressed GST-Ranshi82 and GST-Ranshi137 were raised by injection into rabbits (Pocono Rabbit Farm and Laboratory Inc., PRFL). The α-Ranshi antibodies were affinity-purified by PRFL from rabbit antisera, employing MBP-Ranshi82 and MBP-Ranshi137.

Immunoblot and RNA blot analyses

Total protein from females, female carcasses without ovaries, and ovaries was prepared, immunoblotted, and visualized as described in Mohr et. al. (2001). Anti-Ranshi (0.9 mg/mL) and α-GFP were used at 1:1000 (Invitrogen). Anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Santa Cruz) and anti-mouse HRP (Sigma) were used at 1:5000. As a loading control, after stripping the nitrocellulose membrane with Restore Western Stripping Buffer (Pierce) following recommendations of the supplier, the membranes were probed with the E7 anti-β-tubulin antibody (1:1000; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank).

To obtain poly(A) RNA, ovaries were dissected from females and RNA was isolated as described previously (Mohr et al., 2001). Blotting was performed as described in Mohr et. al. (2001) with the following modifications. To visualize ranshi transcripts, we generated digoxigenin (DIG)-11-UTP labeled single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) probes using the DIG Northern Starter Kit (Roche), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. A 671 bp in vitro transcription template for making RNA probes was generated by PCR from genomic DNA, employing the following PCR primers: 5′-TGGAAGTCCAAAGGGAGTTG-3′ and a reverse primer containing the T7 promoter 5′-taatacgactcactatagggTTAGTGTGAGTCCGCTCGTG-3′.

Results

Ranshi forms an oogenic complex with Mago and Tsu/Y14

In our investigations of Mago and Tsu/Y14, we employed a shotgun proteomics approach to detect proteins in ovarian extracts that co-IP with Mago fused to Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP-Mago), a protein that rescues all phenotypes associated with mago alleles and recapitulates the distribution of endogenous Mago (Newmark et al., 1997; Parma et al., 2007). We used mass spectroscopy to identify proteins in GFP-Mago complexes (Bennett and Boswell, unpublished). In addition to recovering components of the EJC in our immunoprecipitations of GFP-Mago (e.g., Aly/Ref, Tsu/Y14 and others) (Le Hir and Andersen, 2008; Tange et al., 2004), we also identified Ranshi and 53 other proteins that reproducibly co-immunoprecipitate with Mago. Ovarian extracts of wild-type flies constitutively expressing GFP with a nuclear localization signal (nlsGFP) were exploited as a negative control, verifying the specificity of the interactions of the 54 proteins with GFP-Mago complexes.

Since Ranshi co-immunoprecipitates with Mago, we verified that the piggyBac (pBac) transposable element in the ranshi1 allele is within intron 1 of ranshi, ~146 base pairs (bp) downstream of ranshi’s translational initiation site (ATG; see Fig. 1A, B), we constructed a deletion with defined breakpoints within the ranshi locus and a ranshi rescuing transgene (Fig. 1A). Because excision of pBac insertions is precise, we employed Flp recombinase to construct the deletion with defined molecular breakpoints within the ranshi locus (Parks et al., 2004). By inducing recombination between FRT-bearing insertions, ranshi1 and p(XP)d11678, we deleted ~18 kilobasepairs (kbp) of genomic DNA from the site of the ranshi1 insertion and extending distally on chromosome 3R, producing Df(3R)ranshi1 (see Fig. 1A). The deletion removes part of intron 1, exon 1 and the promoter of ranshi, and also deletes DNA from ranshi to CG8223. Sequence analysis was used to verify the deletion breakpoints and indicated that Df(3R)ranshi1 would be useful for phenotypic analysis of ranshi.

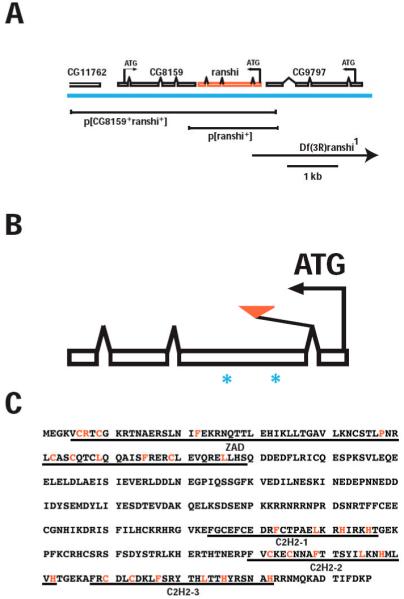

Figure 1.

Genomic organization of ranshi and amino acid sequence of Ranshi. (A) Genomic organization of ranshi showing its position relative to the flanking genes CG11762, CG8159 and CG9797. The centromere is to the left and telomere to the right. The blue horizontal line indicates genomic DNA and above the genomic DNA are predicted transcripts for the genes. For each gene the predicted translational start sites (ATG) and the direction of transcription (arrows) are indicated. Below the genomic DNA the rescuing transgenes and deletion (Df, indicated by the arrow to show that the deletion extends beyond the genomic region depicted) of the genomic region are illustrated. (B) The relative position of ranshi1 (red triangle) and of the regions chosen for generating peptides (*) employed for antibody production are shown. (C) The predicted Ranshi amino acid residues. The domains identified using Pfam to search databases are as follows: zing finger-associated motif (ZAD; amino acid residues 5-79) and the zinc-finger motifs in Ranshi are indicated (C2H2-1, C2H2-2 and C2H2-3).

Given that the ranshi1 allele disrupts the locus identified by mass spectroscopy as encoding Ranshi, we generated rabbit polyclonal antibodies immunoreactive with Ranshi (α-Ranshi). On blots of ovarian poly(A) RNA, we detect an ~1.3 kilobase (kb; see Fig. 2A) transcript potentially encoding a protein of 346 amino acid residues with a predicted Mr of 40.7 kiloDaltons (kDa). Utilizing α-Ranshi on immunoblots of ovarian protein extracts, we detect a single protein with an apparent Mr of ~60 kDa (see Fig. 2B), suggesting the possibility that Ranshi is modified post-translationally. To determine whether the protein identified by α-Ranshi is encoded by the ranshi locus, we immunoblotted ovarian proteins from extracts of wild-type and homozygous ranshi1 females. While α-Ranshi cross-reacts with immunoblotted protein, it is less effective in detecting protein in fixed whole-mount tissues. In ovarian extracts from homozygous ranshi1 females, we observe reduced amounts of Ranshi relative to wild-type ovarian extracts (see Fig. 2B), confirming that the protein detected by α-Ranshi is encoded by the ranshi locus, demonstrating that the pBac insertion alters ranshi expression, and suggesting that ranshi1 is a hypomorphic (reduced function) allele.

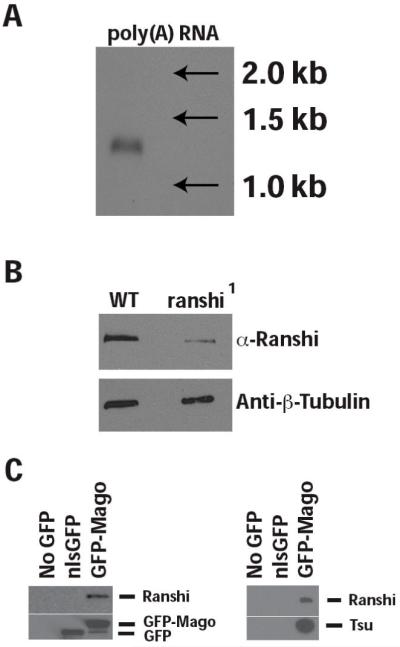

Figure 2.

The ranshi locus encodes a 1.3 kb RNA and an ~60 kDa protein that co-immunoprecipitates with Mago and Tsu/Y14. (A) RNA blot showing that a single ~1.3 kb transcript is detected in ovarian extracts of poly(A) RNA. (B) In ovarian extracts of protein isolated from wild type (WT), α-Ranshi identifies a single protein with an apparent Mr of ~60 kDa. However, in ovarian extracts of homozygous ranshi1 females the amount of Ranshi is reduced, indicating that the antibody is immunoreactive with Ranshi. (C) Immunoprecipitation with anti-GFP attached to beads preferentially immunoprecipitates GFP-Mago, Tsu/Y14 and Ranshi but not nlsGFP.

We next determined whether immunoprecipitation of GFP-Mago resulted in the co-immunoprecipitation of Ranshi and Tsu/Y14. As with the shotgun proteomics experiments, we employed flies carrying the GFP-mago+ transgene. As a negative control, flies carrying the ubi-nlsGFP transgene were utilized to determine whether GFP-Mago specifically co-IPs with Ranshi. To test the ability of Tsu/Y14 to co-IP with Ranshi, we utilized wild-type flies and flies carrying a FLAG-tsu/Y14 transgene (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 2C, when anti-GFP antibody is employed, nlsGFP and GFP-Mago are efficiently and specifically immunoprecipitated from ovarian extracts. When the same blots are reacted with α-Ranshi, Ranshi is undetectable in ovarian extracts lacking nlsGFP or GFP-Mago and preferentially immunoprecipitates with GFP-Mago. In a similar experiment (Fig. 2C), we detect Ranshi and Tsu/Y14 in immunoprecipitates of GFP-Mago but do not detect the proteins in extracts derived from ovaries that lack GFP-Mago or that express nlsGFP, demonstrating the existence of an ovarian complex containing Mago, Tsu/Y14 and Ranshi.

ranshi encodes a protein with a zinc finger-associated domain and zinc finger domains

Database searches, using Pfam 23.0 (Finn et al., 2008; Sonnhammer et al., 1997), reveal that Ranshi contains at least two distinct conserved motifs (Fig. 1C). Amino acid residues 5-79 form a zinc finger-associated domain (ZAD) within Ranshi. ZAD domains are characterized by a group of four conserved cysteines and ~28% of C2H2 zinc finger proteins (ZFP) in Drosophila contain an amino-terminal ZAD (Chung et al., 2002; Lespinet et al., 2002). Although the exact function of ZAD is unknown, the ZAD of Grauzone (a transcription factor specifically required during oogenesis) is known to coordinate zinc and to be involved in homodimerization of Grauzone (Jauch et al., 2003). Within the carboxy-terminus, Ranshi contains at least three C2H2 zinc finger domains (amino acid residues 224-246, 280-302 and 308-332). In addition to functioning as transcription factors, ZFPs are also known to bind RNA (e.g., TFIIIA binding to 5S rRNA), participate in protein-protein interaction through their zinc finger domains (e.g., GATA1 interaction with Friend of GATA-1) and, in some circumstances, the zinc finger domains confer enzymatic activity to proteins (e.g., Modulator of immune recognition; MIR-1) (Brayer and Segal, 2008; Brown, 2005; Coscoy and Ganem, 2003; Gamsjaeger et al., 2007), suggesting that further studies will be required to define the specific role of Ranshi in Mago:Tsu/Y14 complexes.

Ovaries of homozygous ranshi1 females contain 16-cell cysts without an oocyte

To investigate the requirement for ranshi+ function during development, we determined the viability and fertility of homozygous ranshi mutant flies. We found that homozygous ranshi1 males are viable and fertile and indistinguishable from wild type (n=1,012). However, although we found that the viability of homozygous ranshi1 females is identical to wild type, the mutant females fail to lay eggs. In wild-type female ovaries (n= 48), we observed a karyosome (a condensed region of chromosomes detected within the oocyte nucleus) in 98% of stage 3 (S3) egg chambers (Fig. 3A). In contrast, DAPI staining reveals that all egg chambers of homozygous ranshi1 females contain 16 germline cells but the egg chambers lack karyosomes (Fig. 3B; 0/82). Furthermore, the nuclei of all 16 germline cells of cysts derived from homozygous ranshi1 ovaries contain endoreplicated DNA typically observed in nurse cells (Fig. 3B). Our results indicate that homozygous ranshi1 germline cells undergo four mitotic divisions, that oogenesis is blocked prior to S3, and that all germline cells within mutant cysts behave as nurse cells.

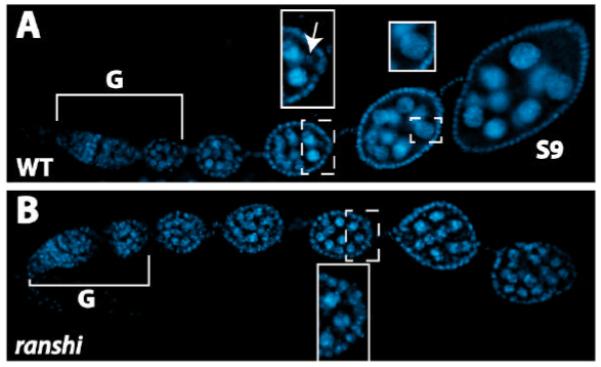

Figure 3.

Ovaries of homozygous ranshi1 females contain 16-cell cysts blocked prior to stage 3 and 16 germline nuclei containing endoreplicated DNA. In both panels anterior is to the left. Brackets define germaria (G) and S9 indicates a stage 9 egg chamber. (A) DAPI staining of a wild-type ovariole. The posterior end of an egg chamber (anterior stippled rectangular box) is magnified in the rectangular box to illustrate the karyosome (indicated by the arrow). A nurse cell nucleus (posterior, stippled, square box) is magnified in the posterior square box to illustrate dispersed chromosomes. (B) DAPI stained ovarioles dissected from homozygous ranshi1 females contain 16-cell cysts and egg chambers without identifiable karyosomes. A posterior pole of an egg chamber is a magnified within the box to illustrate the absence of a karyosome and the presence of nuclei with polytene chromosomes.

The sterility of ranshi1 females reverts to wild type upon excision of the transposable element and is complemented by a rescuing transgene

To determine whether the ovarian phenotype associated with the ranshi1 allele is due to the insertion of the pBac transposable element within the first intron of the gene (see Fig. 1A), we mobilized the pBac, collected independent excision lines, sequenced the ranshi genomic region in the independent excision lines and assessed the phenotypes of the flies. Four independent excision lines were recovered from ~2,500 flies. Sequence analysis revealed that the four independent excision lines are the result of precise excision of the pBac element. All four lines are also phenotypically wild type, indicating that the female sterility and the oogenic block are due to the original pBac insertion within the first intron of ranshi.

We employed P element-mediated transformation to construct flies carrying a ranshi rescuing transgene. The p[CG8159+ ranshi+] (see Fig. 1A) transgene is ~4.2 kbp and begins ~2.4 kbp upstream of the translational initiation site for CG8159 (within CG11762) and extends 436 bp upstream of the translation initiation site of ranshi (within CG9797). The p[CG8159+ ranshi+] transgene rescues the ovarian phenotypes observed in homozygous ranshi1 and hemizygous ranshi1 females, demonstrating that the oogenic block is due to lesions within the ranshi locus.

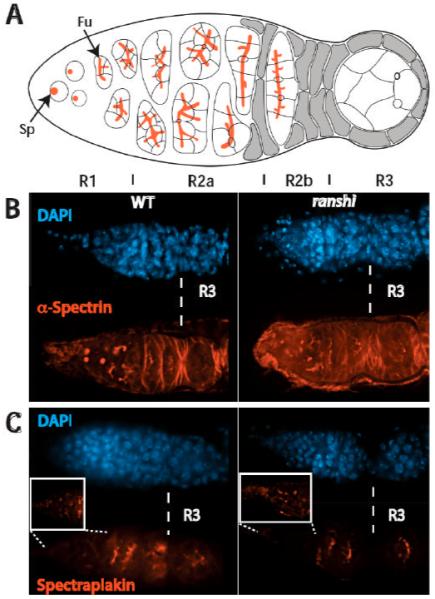

Spectrosome/fusome development is normal in ovaries of homozygous ranshi1 females

Because proper fusome formation and development are known to influence oocyte differentiation (de Cuevas et al., 1996; Grieder et al., 2000; Lin and Spradling, 1995), we compared spectrosome/fusome development in ovaries of wild-type and homozygous ranshi1 females. Two spectrosome/fusome components were examined, α-Spectrin and Spectraplakin. The α-Spectrin protein is a structural component of the spectrosome/fusome and Spectraplakin is a protein associated with spectrosomes/fusomes that is required to organize microtubules on fusomes (Grieder et al., 2000; Röper and Brown, 2004). In the anterior-most part of wild-type germarial region 1 (R1), anti-α-Spectrin detects spectrosomes within GSCs and cystoblasts (CB) (see Fig. 4A, B). At the posterior of R1, when CBs enter the oogenic pathway, anti-α-Spectrin reveals spectrosomes in CBs and branched structures (fusomes) in developing cystocytes. Fusomes persist within the germarium until R2b (Fig. 4A, B). Within germarial region 3 (R3), anti-α-Spectrin occasionally detects discontinuous structures, representing degenerating fusomes. When germaria of homozygous ranshi1 females are reacted with anti-α-Spectrin spectrosome/fusome development is indistinguishable from wild type (n= 210; Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Spectrosome/fusome development in ovaries of homozygous ranshi1 females is indistinguishable from wild type. In all panels, anterior is to the left. (A) Cartoon of a germarium. Spectrosomes (Sp) and fusomes (Fu) are illustrated in red. Vertical lines demarcate germarial regions 1 (R1), 2a (R2a), 2b (R2b) and 3 (R3). (B) Spectrosome/fusome development in wild-type (left) and homozygous ranshi1 females are similar. In both (B) and (C), R3 is to the right of the dotted vertical line. (C) The distribution of Spectraplakin in wild-type and homozygous ranshi1 germaria is indistinguishable. The boxes contain magnified photographs of the anterior tip of the germaria to show the presence of spectrosomes.

Spectrosomes and fusomes lacking functional Spectraplakin are similar to wild type when assessed employing anti-α-Spectrin (Röper and Brown, 2004). Although spectrosome/fusome development is apparently normal in Spectraplakin deficient germaria, 16-cell cysts without an oocyte are formed. In the presence of microtubule depolymerizing drugs Spectraplakin is detected on fusomes, suggesting that the association of Spectraplakin with fusomes is independent of dynamic microtubules (Röper and Brown, 2004). Spectraplakin contains a GAS2 domain, a microtubule-binding domain (Karakesisoglou et al., 2000; Lee and Kolodziej, 2002; Sun et al., 2001). Röper and Brown (2004) propose that Spectraplakin associates with fusomes through a domain other than the GAS2 domain, and that the GAS2 domain is utilized to recruit and to influence the polarization of microtubules and the transport of components to the oocyte. Therefore, we examined the distribution Spectraplakin in homozygous ranshi1 ovaries. The distribution of Spectraplakin in wild-type germaria is identical to α-Spectrin in R1-R2b (Fig. 4C) (Röper and Brown, 2004). In R3, where α-Spectrin is undetectable or only detected in fragments, Spectraplakin persists in what appear to be remnants of the fusome (Fig. 4C). In ovaries of homozygous ranshi1 females, the distribution of Spectraplakin is identical to wild-type germaria (n= 70; Fig. 4C), showing that Spectraplakin associates with fusomes in ovaries of homozygous ranshi1 females. Our results from the analysis of α-Spectrin and Spectraplakin accumulation within germaria of homozygous ranshi1 females show that spectrosome/fusome development is not obviously disrupted, and that a fusome component (Spectraplakin) required for recruiting and organizing microtubules within cysts is normal.

Restriction of meiosis to a single cell is aberrant in ranshi mutant germaria

SC formation is the first indicator of oocyte differentiation (Huynh and St Johnston, 2004). Mutations in genes required for oocyte specification (e.g., BicD and egl) and for oocyte maintenance (e.g., par-1) produce R2a cysts in which all cells contain SCs (Huynh and St Johnston, 2000; Huynh et al., 2001). To examine SC formation in wild-type and ranshi mutant germaria, we employed antibodies immunoreactive with the SC component C(3)G (Page and Hawley, 2001). In wild-type germaria, α-C(3)G first detects SCs in two adjacent cells within R2a and then four adjacent cells contain SCs (Fig. 5A). As wild-type cysts enter anterior R2b, SCs are lost from two of the four adjacent cells and are retained only within the two pro-oocytes. Once wild-type cysts enter posterior R2b, a single cell (n= 118), the presumptive oocyte, retains SC and the SC persists within the oocyte from R3 (stage 1 egg chamber; S1) until egg chambers reach oogenic stage 6 (S6).

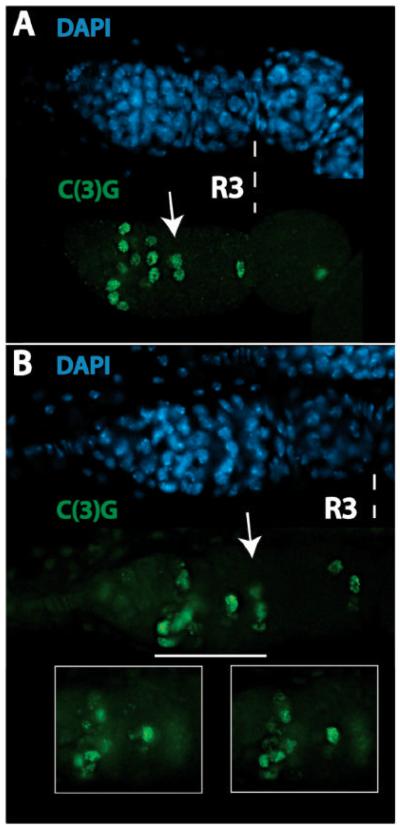

Figure 5.

Restriction of meiosis to a single cell requires ranshi+ function. In all panels, anterior is to the left and R3 indicates germarial region 3. (A) Synaptonemal complex formation and meiotic progression in a wild-type germarium. The arrow identifies a R2b cyst with two adjacent cells (pro-oocytes) that are C(3)G positive. (B) In ranshi mutant germaria meiosis is not restricted to a single cell, as assessed by the presence of synaptonemal complexes in two adjacent cells within R3. The arrow identifies a R2b cyst with at least 3 adjacent cells with synaptonemal complexes. The white horizontal line delineates the germarial region magnified in the boxes and shows synaptonemal complexes within different focal planes.

Meiotic progression in ranshi mutant germaria is distinct from wild type when examined employing α-C(3)G. Although homozygous ranshi1 and hemizygous ranshi1 ovaries are not distinguishable when analyzed for the presence of polyploid nuclei, for spectrosome/fusome development, or for the localization of a fusome-associated component (Spectraplakin), the development of homozygous and hemizygous mutant germline cells is different when examined for SC formation and meiotic progression. Employing α-C(3)G to assess meiotic progression in wild-type, homozygous ranshi1, and hemizygous ranshi1 cysts, we observe no differences within R2a (n= 313), suggesting that entry into meiosis is normal in ranshi mutant cysts. However, under our experimental conditions, ~60% (n= 83) of homozygous ranshi1 S1 egg chambers contain a single cell with SC. The remaining ~40% of homozygous ranshi1 S1 egg chambers have two adjacent cells with SCs. In contrast, ~83% (n= 100) of S1 egg chambers from hemizygous ranshi1 ovaries have two adjacent cells with SCs (Fig. 5B) when assessed for the presence of C(3)G positive cells. The remaining S1 egg chambers of hemizygous ranshi1 ovaries have either a single cell with SC (~10%) or 3-4 adjacent cells with SCs (~7%). Regardless of whether the S1 egg chamber has one or more C(3)G positive cells, ~80% (n= 49) of the egg chambers have a C(3)G positive cell within the posterior end. In wild-type cysts, positioning of the oocyte within the posterior pole requires oocyte-posterior follicle interactions (Godt and Tepass, 1998; González-Reyes and St. Johnston, 1998). The fact that, in the majority of ranshi egg chambers, a C(3)G positive cell is observed within the posterior pole suggests that at least one of the two pro-oocytes in these egg chambers is sufficiently oocyte-like to form proper interactions with posterior follicle cells, and to move from a central position within a cyst to a posterior position. In post-germarial stages, both homozygous and hemizygous ranshi1 egg chambers retain SC, showing that maintenance of meiosis is not altered. Consistent with the immunoblotting results (see Fig. 2B), the phenotypic difference we observe between homozygous ranshi1 and hemizygous ranshi1 ovaries indicates that ranshi1 is a reduced function allele and that impairing Ranshi+ function results in a failure to restrict oocyte fate to a single cell within the 16-cell cyst. Furthermore, these results also demonstrate that SC formation and meiotic progression in ranshi mutant germaria are different from mutant germaria with a block in oocyte specification (e.g., BicD, egl and others) or in oocyte maintenance (e.g., par-1), suggesting that Ranshi is not essential for restricting entry into meiosis to four cells in the 16-cell cyst or for maintaining meiosis in cysts and in post-germarial stages.

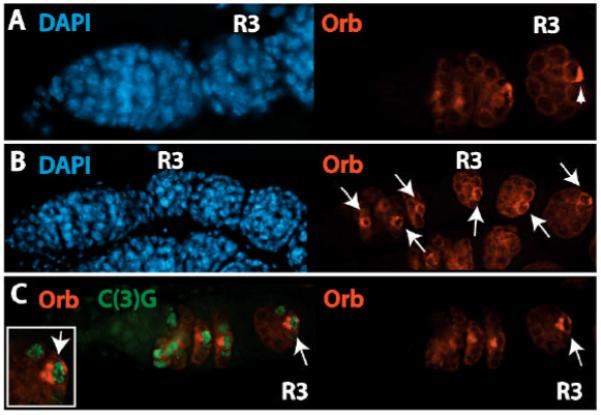

Ranshi is required to localize oocyte-specific markers within the oocyte’s posterior pole

We examined the distribution of the oocyte markers BicD, Egl, Orb and Tsu/Y14 within homozygous and hemizygous ranshi1 germaria in order to investigate whether mutations in ranshi produce a germarial phenotype similar to or distinct from mutations in genes required for oocyte specification and/or maintenance. In germaria lacking gene functions required for oocyte specification (e.g., BicD, egl, orb and tsu) the directed transport to and accumulation of Orb within the two pro-oocytes and oocyte is not observed, indicating that the second step in oocyte differentiation is abnormal (Lantz et al., 1994; Mach and Lehmann, 1997; Parma et al., 2007; Suter and Steward, 1991). Germaria deficient for gene functions essential for oocyte maintenance (e.g., par-1) accumulate oocyte-specific markers such as Orb within the pro-oocytes and the presumptive oocyte, but the markers fail to translocate from the anterior to the posterior pole of the presumptive oocyte and are lost from the presumptive oocyte in post-germarial stages (Huynh et al., 2001). Thus, the distribution of oocyte-specific markers within mutant germaria can be used to determine whether a gene function is indispensable for oocyte specification or oocyte maintenance. Therefore, we investigated the distribution of BicD (n= 68), Egl (n= 61), Orb and Tsu/Y14 (n= 74) within ovarioles of wild-type and ranshi mutant females. Because the accumulation of BicD, Egl, Orb and Tsu/Y14 within germline cells of ranshi mutant ovaries is identical (data not shown), we only present data for Orb accumulation in ranshi mutant ovarioles. Furthermore, the distribution of Orb is the same in ovaries of homozygous ranshi1 (n= 118) and hemizygous ranshi1 females (n= 119) and, thus, we employ the term ranshi to describe mutant ovarian tissues.

The distribution of BicD, Egl, Orb and Tsu/Y14 in ranshi cysts deviates from wild type within R2b (compare Fig. 6A and B). In ranshi R2b cysts, containing a single germline cell with SC, the cell with SC has detectable Orb but the protein is not localized within a pole of the cell. Instead, Orb is evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm of the cell, suggesting that transport of BicD, Egl, Orb and Tsu/Y14 to the pro-oocytes and oocyte is normal but that the localization of the proteins within the presumptive oocyte is anomalous. Employing ring canals as an additional marker of the oocyte (one of the two cells with four ring canals), in S1 egg chambers, we detect Orb only within germline cells with four ring canals (32/32) providing further support that Orb accumulates within the presumptive oocyte. In ranshi cysts containing two germline cells with SCs, one of the two cells with SCs accumulates BicD, Egl, Orb (41/41) and Tsu/Y14 and the proteins are evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm of the SC containing cell (see Fig. 6C). The formation of the SC and the distribution of BicD, Egl, Orb and Tsu/Y14 in ranshi germline cells indicate that the transport to and accumulation of oocyte markers within the pro-oocytes is normal, but that translocation of the markers from the anterior to the posterior pole of the presumptive oocyte is defective. Post-germarial ranshi egg chambers contain Orb positive cells (see Fig. 6B), suggesting that ranshi+ function is not required for maintaining Orb within the presumptive oocyte but is necessary for localization of Orb within the posterior pole.

Figure 6.

Accumulation of Orb within a single cell of 16-cell cysts is independent of ranshi+ but posterior pole localization of Orb requires Ranshi. In all panels, anterior is to the left and (R3) is germarial region 3. (A) Orb distribution within a wild-type germarium. The arrowhead indicates posterior localization of Orb in R3. (B) In ranshi ovaries Orb is detected within a single cell within 16-cell cysts but is evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm of the cell. Orb persists in post-germarial egg chambers (indicated by the arrows). (C) Although adjacent cells within ranshi germaria are C(3)G positive, only one cell contains Orb, indicated by the arrow and magnified in the inset.

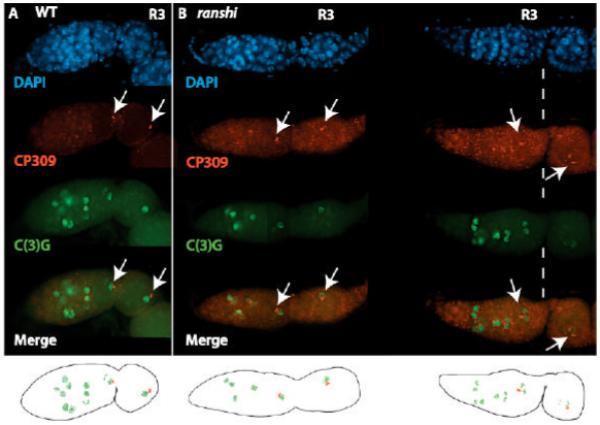

Ranshi is required for the posterior pole localization of centrosomes within the presumptive oocyte

Centrosome accumulation within 16-cell cysts serves as another marker of the progression of oocyte differentiation (Bolivar et al., 2001; Grieder et al., 2000). Unlike BicD, Egl and Orb, however, centrosomes concentrate within the oocyte in the presence of microtubule depolymerizing drugs (Bolivar et al., 2001). In Spectraplakin or Dhc64C deficient germaria (Bolivar et al., 2001), centrosomes are associated with fusomes in R1 and R2a but centrosomes fail to migrate to the oocyte in R2b and R3, indicating that Spectraplakin and Dhc64C are necessary for the directed transport of centrosomes to the oocyte and that the transport of centrosomes to the oocyte is dependent on microtubules resistant to microtubule depolymerizing drugs; i.e., stable microtubules. BicD and Egl, proteins that interact with one another and with Dynein/Dynactin to transport components to the oocyte, are not essential for the migration of centrosomes to the oocyte (Bolivar et al., 2001; Mach and Lehmann, 1997; Matanis et al., 2002; Navarro et al., 2004). To investigate whether the accumulation of centrosomes within the oocyte is dependent on ranshi+ function, we utilized antibodies against the Drosophila Pericentrin-like protein, α-CP309 (Kawaguchi and Zheng, 2004; Martinez-Campos et al., 2004). We observe centrosomes concentrated within the presumptive oocyte in wild-type R2b and, in wild-type R3, centrosomes are localized within the oocyte, posterior to the oocyte nucleus (n= 63; see Fig. 7A). In ranshi cysts (homozygous or hemizygous), containing a single cell with SC, centrosomes assemble within the C(3)G positive cell in R2b and R3 cysts (n= 89; see Fig. 7B). However, in ranshi cysts, centrosomes are not detected within the posterior of the cell with SC but are randomly placed within the cytoplasm of the SC containing cell. Centrosomes are associated with a single cell in ranshi R3 cysts containing two cells with SC (homozygous ranshi1, n= 33, and hemizygous ranshi1, n= 35). The accumulation of centrosomes within a single cell in R2b and R3 of ranshi ovaries provides further evidence that the association of Spectraplakin with fusomes is not disrupted and suggests that Dhc64C is functional in the mutant cysts, resulting in the directed transport of centrosomes to the presumptive oocyte.

Figure 7.

Centrosomes accumulate within one cell of ranshi 16-cell cysts but fail to localize within the posterior pole of the cell. In both panels, anterior is to the left, α-CP309 is employed to detect centrosomes, α-C(3)G detects synaptonemal complexes, arrows point to centrosomes and R3. (A) The progression of synaptonemal complex formation and the distribution of centrosomes in a wild-type germarium. (B) In ranshi germaria, centrosomes accumulate within the anterior pole of a single cell but fail to translocate to the posterior pole. In ranshi cysts containing two adjacent cells with synaptonemal complexes, centrosomes accumulate in one of the two cells with synaptonemal complexes. Below are cartoons of the merged CP309 and C(3)G images for wild-type and ranshi germaria.

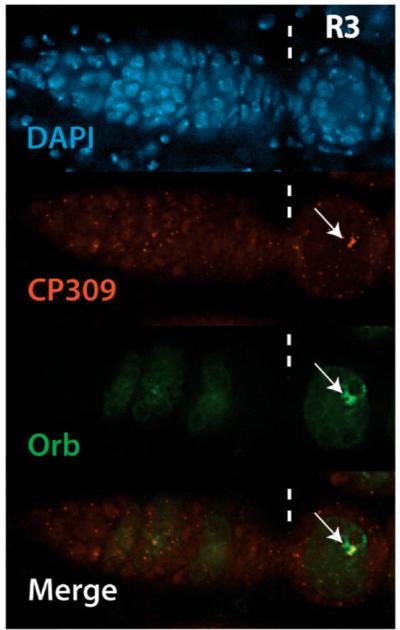

To investigate whether centrosomes and Orb accumulate within the cytoplasm of the same cell in ranshi cysts, we employed both α-CP309 and α-Orb. In all homozygous ranshi1 (n= 58) and hemizygous ranshi1 (n= 98) S1 egg chambers examined (Fig. 8), centrosomes are detected in the Orb positive cell. The restriction of BicD, Egl, Orb, Tsu/Y14 and centrosomes to a single cell, and our observation that Orb and centrosomes accumulate within the same cell suggest that a single cystocyte is specified as an oocyte in ranshi ovaries but that the cell fails to differentiate.

Figure 8.

Orb and centrosomes accumulate within the same cell in ranshi egg chambers. Illustrated is a ranshi germarium with posterior to the left and vertical dashed lines marking germarial region 3 (R3). The arrows indicate centrosomes (red) labeled with α-309 and Orb (green) labeled with α-Orb accumulating in one cell of a ranshi stage 1 egg chamber, indicating that an oocyte is specified in ranshi ovaries.

Discussion

Genetic analyses of core components of the EJC in Drosophila show that the proteins (Barentsz/MLN51, eIF4AIII, Mago and Tsu/Y14) are essential for the localization of mRNA during oogenesis (e.g., oskar mRNA within the posterior pole) (Hachet and Ephrussi, 2001; Mohr et al., 2001; Newmark et al., 1997; Palacios et al., 2004; van Eeden et al., 2001). Our studies of Mago and Tsu/Y14 show that the proteins function multiple times during oogenesis to influence discrete oogenic events (Mohr et al., 2001; Newmark et al., 1997; Parma et al., 2007). Here we used a shotgun proteomics and genetic approach to identify proteins in complexes with Mago and to determine the role of one of the proteins during oogenesis. Our biochemical and genetic analyses of females homozygous or hemizygous for ranshi1 demonstrate that the locus encodes a protein that forms an ovarian complex with core components of the EJC (Mago and Tsu/Y14) and that Ranshi is required for localizing factors essential for oocyte development within the posterior pole of the presumptive oocyte, indicating that Ranshi interacts with the EJC to influence oocyte differentiation.

Microtubule-based transport within ovarian cysts is not disrupted in homozygous and hemizygous ranshi1 females

In homozygous and hemizygous ranshi1 germaria, 16-cell cysts form but all nuclei contain endoreplicated DNA, suggesting that the cells have entered the nurse cell pathway. Thus far, this early oogenic phenotype has been observed in mutants of genes encoding components required for organizing the microtubule network and for microtubule-based transport within cysts (Huynh and St Johnston, 2004). Several results demonstrate that the microtubule-dependent polarized transport of components essential for oocyte selection and maintenance is functional in ranshi cysts. Fusomes and fusome-associated proteins are required for organizing the polarized microtubule network that transports components from the pro-nurse cells into the pro-oocyte and presumptive oocyte (de Cuevas and Spradling, 1998; Deng and Lin, 1997; Grieder et al., 2000; Huynh and St Johnston, 2000; Lin and Spradling, 1995; Röper and Brown, 2004; Theurkauf et al., 1993). The fusomes in ranshi germline cells appear identical to wild-type fusomes when examined employing antibodies immunoreactive with α-Spectrin (a structural component of fusomes) and Spectraplakin (a fusome-associated protein required for recruiting microtubules to fusomes), suggesting that fusome structure and development are normal in ranshi germline cells. Although synaptonemal complexes form in germline cells lacking Spectraplakin, within germarial regions 2b and 3 all cystocytes have exited meiosis (Röper and Brown, 2004). This is distinct from ranshi cysts in which entry into meiosis is identical to wild type but two cells remain in meiosis within germarial regions 2b and 3 and meiosis is maintained in the two cells during post-germarial stages. The migration of centrosomes to the presumptive oocyte is dependent on both Spectraplakin and Dhc64C (Bolivar et al., 2001; Röper and Brown, 2004). Within ranshi cysts Dhc6C localizes as in wild type (data not shown) and centrosomes migrate to a single cell, one of the two pro-oocytes. The normal structure and development of the fusomes, the proper localization of Dhc64C, and the migration of centrosomes to a single cell within ranshi cysts indicate that the polarization of germline cysts is unimpaired.

Once a polarized microtubule network is established in germline cysts, proteins such as BicD, Egl, Orb, Par-1 and Tsu/Y14 are first transported to the pro-oocytes and finally to the presumptive oocyte where the proteins influence oocyte selection, maintenance, and differentiation (Cox et al., 2001; Huynh and St Johnston, 2000; Huynh et al., 2001; Lantz et al., 1994; Mach and Lehmann, 1997; Parma et al., 2007; Suter et al., 1989; Suter and Steward, 1991; Vaccari and Ephrussi, 2002; Wharton and Struhl, 1989). BicD and Egl directly interact, forming an oogenic complex required for the polarized transport of factors to the pro-oocytes and oocyte. The complex is also essential for oocyte specification (i.e., in BicD and egl null germline cells, 16-cell cysts are formed but none remain in meiosis) (Dienstbier et al., 2009; Huynh and St Johnston, 2000; Mach and Lehmann, 1997; Navarro et al., 2004; Suter et al., 1989; Suter and Steward, 1991). Results from recent studies indicate that Egl is a RNA-binding protein that recognizes mRNA localization signals and that Egl can also form a complex with the Drosophila dynein light chain (Dlc) (Dienstbier et al., 2009; Navarro et al., 2004). Distinct domains of Egl are employed in its interaction with Dlc and with BicD. BicD is known to form a complex with dynein/dynactin motor complexes in mammalian cells and, in Drosophila, dynein-dependent directed transport of RNA requires both BicD and Egl to form an active complex (Dienstbier et al., 2009; Hoogenraad et al., 2001; Hoogenraad et al., 2003; Matanis et al., 2002). In mutant BicD and egl germaria, components necessary for oocyte differentiation fail to accumulate within the pro-oocytes or the presumptive oocyte. However, we found that in ranshi cysts, the transport of BicD, Egl, Orb and Tsu/Y14 to the pro-oocytes and presumptive oocyte is indistinguishable from wild type, indicating that BicD and Egl-dependent transport to the oocyte is functioning.

Because mutations in Dlc and within the Dlc interaction domain of Egl do not disrupt the restriction of synaptonemal complexes to a single cell, it is thought that BicD and Egl function independently of microtubule-directed transport in oocyte selection (Navarro et al., 2004). Our finding that ranshi cysts enter meiosis properly indicates that BicD and Egl are able to participate in the initial restriction of oocyte fate within the mutant cysts, providing evidence that entry into the oogenic pathway is normal in ranshi germaria. Considered together, our analyses of fusome structure and function and the transport of oocyte-specific factors within wild-type and ranshi cysts indicate that Ranshi is vital for an oogenic process that occurs after the establishment of a polarized microtubule network within cysts and after transport of components to the pro-oocytes.

Oocyte maintenance is normal in germaria of homozygous and hemizygous ranshi1 females

In mutant cysts lacking components required for oocyte maintenance (e.g., Par-1), oocyte markers (e.g., BicD, Egl, etc.) accumulate within the pro-oocytes and later are restricted to the presumptive oocyte (Cox et al., 2001; Huynh et al., 2001). However, in cysts devoid of components essential for oocyte maintenance (e.g., par-1 null), the translocation of oocyte markers from the anterior to the posterior pole of the presumptive oocyte is defective (germarial region 2b), oocyte markers are lost from the presumptive oocyte in germarial regions 2b and 3, and while the synaptonemal complex is restricted to a single cell in germarial region 3 egg chambers, in post-germarial stages the synaptonemal complex is undetectable. Within ranshi germarial region 2b cysts oocyte markers are restricted to a single cell, the same cell that contains the centrosomes (one of the two cells with four ring canals and synaptonemal complexes). Nevertheless, oocyte-specific markers fail to translocate from the anterior to the posterior pole of the cell and fill the cytoplasm of the presumptive oocyte. Although centrosomes are detected within a single cell in ranshi germarial region 2b and 3 cysts, the centrosomes appear to be randomly placed within the cytoplasm of the presumptive oocyte. Importantly, unlike par-1 null egg chambers, in post-germarial stages of ranshi ovaries, a single cell retains oocyte-specific cytoplasmic markers. The accumulation of oocyte-specific markers and centrosomes within a single cell and the persistence of the markers and centrosomes in post-germarial stages suggests that in ranshi germline cells, a single cell is selected and maintained in the oogenic pathway but differentiation is impaired. Thus, our analyses utilizing available ranshi alleles indicate that oocyte maintenance is not defective in ranshi cysts, but that posterior pole localization of factors crucial for oocyte differentiation is blocked.

The ranshi ovarian phenotype is distinct from ovaries defective in the cell-cycle program or meiotic progression

Oocyte selection is also dependent on the proper execution of the cell-cycle program and appropriate progression of meiotic events within germline cysts (Huynh and St Johnston, 2004). Mutations in genes encoding the cell-cycle regulators, cycE (encoding cyclin E, a cyclin that regulates replication and endoreplication) and p27cip/kip/dacapo (dap, encoding a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, a negative regulator of cyclin E), alter oocyte differentiation (Hong et al., 2003; Lilly and Spradling, 1996). In ovaries homozygous for a reduced function allele of cycE (cycE01672), 2-3 cells within the 16-cell cyst differentiate as oocytes, producing mature eggs with multiple germinal vesicles. Dacapo (Dap) protein specifically accumulates within the oocyte nucleus in germarial region 3 (stage 1 egg chambers), where Dap inhibits cyclin E activity, preventing the oocyte nucleus from entering the endocycle and maintaining the oocyte nucleus in prophase I of meiosis (de Nooij et al., 2000; Hong et al., 2003). In dap null germline cysts, all cells enter the endocycle and restriction of SC to a single cell is delayed until germarial region 3 (Hong et al., 2003). Initially, dap null cysts accumulate Orb and BicD within a single cell, and by germarial region 3 the mutant cysts no longer show detectable Orb or BicD. In dap null cysts, where the oocyte nucleus has undergone limited polyploidization, Orb and BicD are maintained within the oocyte and the egg chambers develop, but arrest during stage 6 or 7. These results led Hong et. al. (2003) to propose that the greater the endoreplication of the oocyte nucleus the less likely that oocyte differentiation would progress properly; i.e., the greater the polyploidy of the oocyte nucleus the less likely that Orb and other oocyte-specific markers would accumulate within the cytoplasm of the presumptive oocyte. Two phenotypic differences between dap null and ranshi cysts lead us to propose that the block in oocyte differentiation in Ranshi deficient ovaries might be due to disruption of a Dap-independent pathway. First, in the absence of Dap the polyploidy of the oocyte nucleus is variable. However, the polypoloidy of the 16 nuclei in ranshi cysts is invariant and indistinguishable from that of wild-type nurse cell nuclei, indicating that in ranshi cysts all germline cells have undergone endoreplication that is indistinguishable from cells that have entered the nurse cell pathway. Second, unlike dap null cysts, a single cell within ranshi cysts accumulates and retains oocyte-specific cytoplasmic markers and the markers are detectable within a single cell during post-germarial stages. Thus, in ranshi cysts, the extent of polyploidy does not interfere with the restriction of oocyte-specific cytoplasmic markers to a single cell. Therefore, our phenotypic analyses of ranshi cysts suggest that the block in oocyte differentiation observed in ranshi cysts is distinct from that observed in dap null cysts.

Mutations in genes encoding proteins required for meiotic exchange, the distribution of meiotic crossovers, and DNA double-stranded break (DSB) repair delay but do not block oocyte selection. For example, in spindle-B (spn-B, encoding the Drosophila homolog of yeast RAD51) and okra (okr, encoding the Drosophila homolog of yeast RAD54) mutant ovaries, DSBs are not repaired, synaptonemal complexes are retained in the two pro-oocytes until germarial region 3 or stage 2 egg chambers, and oocyte-specific markers concentrate in the two pro-oocytes instead of the presumptive oocyte. In later stage spn-B and okr mutant egg chambers, a single cell retains SC and oocyte-specific markers are not restricted to the cytoplasm of the presumptive oocyte (Ghabrial et al., 1998; Ghabrial and Schüpbach, 1999; González-Reyes et al., 1997). The Drosophila homolog of yeast SPO11 (an endonuclease that catalyzes the formation of DSBs) is encoded by mei-W68 (McKim and Hayashi-Hagihara, 1998). In ovaries doubly mutant for mei-W68 and spn-B or okr, the delay in oocyte selection is suppressed, suggesting that oocyte selection is perturbed in spn-B and okr mutant ovaries due to activation of a meiotic DNA-repair checkpoint (Ghabrial and Schüpbach, 1999). Activation of a DSB-independent checkpoint has also been shown to delay oocyte selection. Mutations in genes encoding components of the DSB-independent checkpoint produce phenotypes similar to those observed in spn-B and okr mutant ovaries (Joyce and McKim, 2009). To determine whether oocyte differentiation is blocked in ranshi ovaries due to a failure of meiotic progression or whether meiotic progression is blocked due to a disruption of events required for oocyte differentiation will require additional studies. However, the fact that null mutations in genes required for meiotic progression only delay oocyte differentiation suggests that in ranshi cysts additional oogenic processes are disrupted, resulting in a block in progression into the oogenic pathway.

Ranshi forms a complex with EJC components and influences posterior pole localization of oocyte differentiation factors within the presumptive oocyte

In Drosophila, the EJC is involved in nuclear export, translational regulation, and RNA localization (Gehring et al., 2009; Tange et al., 2004). The core components of the EJC are deposited on spliced RNAs within the nucleus (eIF4AIII, Mago and Tsu/Y14) and the proteins remain bound to mRNAs within the cytoplasm, until removed during translation (Dostie and Dreyfuss, 2002; Gehring et al., 2009; Giorgi and Moore, 2007; Le Hir and Andersen, 2008; Tange et al., 2004). Although some core components of the EJC bind RNA directly (eIF4AIII and Barentsz/MLN51), the binding appears to be independent of RNA structure or sequence (Le Hir et al., 2000). Given the absence of apparent secondary structure or sequence motif for RNA binding of the EJC, it has been proposed that the core components serve as a platform for the binding of additional proteins that provide specificity for mRNA localization within distinct sub-cellular compartments (Le Hir and Andersen, 2008).

Ranshi co-immunoprecipitates with Mago and Tsu/Y14, and oocyte differentiation is aberrant in magonull germline clones, tsunull germline clones and ranshi ovaries, suggesting that Ranshi interacts with the platform generated by the core components of the EJC to influence oocyte differentiation. Mago and Tsu/Y14 are predominantly nuclear in germline and ovarian somatic cells within germarial region 1 (Parma et al., 2007). In germarial regions 2b and 3, Mago and Tsu/Y14 are detected within nuclei and are also observed accumulating within the cytoplasm of the pro-oocytes and presumptive oocyte, and in germarial region 3 the proteins are localized within the oocyte’s posterior pole cytoplasm, presumably associated with mRNAs encoding proteins necessary for oocyte differentiation. Because the antibodies immunoreactive with Ranshi do not detect protein in whole-mount ovaries, we were unable to determine Ranshi’s sub-cellular distribution during oogenesis.

Ranshi contains two identifiable motifs, a zinc finger-associated domain and C2H2 zinc finger domain. Zinc finger domains are found in transcription factors, RNA-binding proteins and chromatin components (Brayer and Segal, 2008; Brown, 2005; Laity et al., 2001). In addition to participating in DNA and RNA binding, zinc finger domains can function in protein-protein interactions (Brayer and Segal, 2008). Structural analyses of the zinc finger-associated domain of the Drosophila transcription factor, Grauzone, reveal that the zinc finger-associated domain functions in homodimerization or as a protein-protein interaction module (Jauch et al., 2003). Additional studies will be required to determine the biochemical function of Ranshi in the EJC and the role of the zinc finger-associated domain and the zinc finger domains in Ranshi’s interactions with the EJC. Regardless of whether Ranshi is primarily a nuclear protein, cytoplasmic protein or both, the ranshi ovarian phenotype indicates that Ranshi interacts with the EJC to localize components required for oocyte differentiation. In homozygous and hemizygous ranshi1 ovaries, centrosomes, BicD, Egl, Orb and Tsu/Y14 are transported to and accumulate within a single cell of the 16-cell cyst, and their transport and accumulation are indistinguishable from wild type, indicating that nuclear export of RNA is not the likely defect in the mutant ovaries. Instead, our results are consistent with a model in which Ranshi interacts directly or indirectly with core components of the EJC to influence the (a) selective translation of mRNAs encoding components critical for localizing differentiation factors within the oocyte’s posterior pole or (b) posterior pole localization of mRNAs encoding oocyte differentiation factors within the oocyte.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by a NIH training grant to P.E.B. and a NIH grant (GM57989) to R.E.B.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- al-Mukhtar KA, Webb AC. An ultrastructural study of primordial germ cells, oogonia and early oocytes in Xenopus laevis. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1971;26:195–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolivar J, Huynh JR, Lopez-Schier H, Gonzalez C, St Johnston D, Gonzalez-Reyes A. Centrosome migration into the Drosophila oocyte is independent of BicD and egl, and of the organisation of the microtubule cytoskeleton. Development. 2001;128:1889–1897. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.10.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayer KJ, Segal DJ. Keep your fingers off my DNA: protein-protein interactions mediated by C2H2 zinc finger domains. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2008;50:111–131. doi: 10.1007/s12013-008-9008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RS. Zinc finger proteins: getting a grip on RNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2005;15:94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büning J. The Insect Ovary: Ultrastructure, Previtellogenic Growth and Evolution. Chapman & Hall; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter ATC. Electron microscopy of meiosis in Drosophila melanogaster females. I. Structure, arrangement, and temporal change of the synaptonemal complex in wild-type. Chromosoma. 1975;51:157–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00319833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HR, Schafer U, Jackle H, Bohm S. Genomic expansion and clustering of ZAD-containing C2H2 zinc-finger genes in Drosophila. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:1158–1162. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggins LW. An ultrastructural and radioautographic study of early oogenesis in the toad Xenopus laevis. J. Cell Sci. 1973;12:71–93. doi: 10.1242/jcs.12.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coscoy L, Ganem D. PHD domains and E3 ubiquitin ligases: viruses make the connection. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DN, Lu B, Sun TQ, Williams LT, Jan YN. Drosophila par-1 is required for oocyte differentiation and microtubule organization. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:75–87. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RT, Spradling AC. A Balbiani body and the fusome mediate mitochondrial inheritance during Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 2003;130:1579–1590. doi: 10.1242/dev.00365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cuevas M, Lee JK, Spradling AC. alpha-spectrin is required for germline cell division and differentiation in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 1996;122:3959–3968. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cuevas M, Lilly MA, Spradling AC. Germline cyst formation in Drosophila. Ann. Rev. Genet. 1997;31:405–428. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.31.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cuevas M, Spradling AC. Morphogenesis of the Drosophila fusome and its implications for oocyte specification. Development. 1998;125:2781–2789. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Nooij JC, Graber KH, Hariharan IK. Expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Dacapo is regulated by cyclin E. Mech. Dev. 2000;97:73–83. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00435-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Lin HF. Spectrosomes and fusomes anchor mitotic spindles during asymmetric germ cell divisions and facilitate the formation of a polarized microtubule array for oocyte specification in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 1997;189:79–94. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienstbier M, Boehl F, Li X, Bullock SL. Egalitarian is a selective RNA-binding protein linking mRNA localization signals to the dynein motor. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1546–1558. doi: 10.1101/gad.531009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostie J, Dreyfuss G. Translation is required to remove Y14 from mRNAs in the cytoplasm. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1060–1067. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy EM. Germ plasm and differentiation of the germ line. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1975;43:229–280. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ephrussi A, Dickinson LK, Lehmann R. oskar organizes the germ plasm and directs localization of the posterior determinant nanos. Cell. 1991;66:37–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90137-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ephrussi A, Lehmann R. Induction of germ cell formation by oskar. Nature. 1992;358:387–392. doi: 10.1038/358387a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Extavour CG, Akam M. Mechanisms of germ cell specification across the metazoans: epigenesis and preformation. Development. 2003;130:5869–5884. doi: 10.1242/dev.00804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, Tate J, Mistry J, Coggill PC, Sammut SJ, Hotz HR, Ceric G, Forslund K, Eddy SR, Sonnhammer EL, Bateman A. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D281–D288. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamsjaeger R, Liew CK, Loughlin FE, Crossley M, Mackay JP. Sticky fingers: zinc-fingers as protein-recognition motifs. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007;32:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard DL, Affleck D, Error BM. Microtubule organization, acetylation, and nucleation in Xenopus laevis oocytes: II. A developmental transition in microtubule organization during early diplotene. Dev. Biol. 1995;168:189–201. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring NH, Lamprinaki S, Kulozik AE, Hentze MW. Disassembly of exon junction complexes by PYM. Cell. 2009;137:536–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghabrial A, Ray RP, Schüpbach T. okra and spindle-B encode components of the RAD52 DNA repair pathway and affect meiosis and patterning in Drosophila oogenesis. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2711–2723. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.17.2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghabrial A, Schüpbach T. Activation of a meiotic checkpoint regulates translation of Gurken during Drosophila oogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:354–357. doi: 10.1038/14046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi C, Moore MJ. The nuclear nurture and cytoplasmic nature of localized mRNPs. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;18:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godt D, Tepass U. Drosophila oocyte localization is mediated by differential cadherin-based adhesion. Nature. 1998;395:387–391. doi: 10.1038/26493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Reyes A, Elliott H, St. Johnston D. Oocyte determination and the origin of polarity in Drosophila: the role of the spindle genes. Development. 1997;124:4927–4937. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.24.4927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Reyes A, St. Johnston D. The Drosophila AP axis is polarised by the cadherin-mediated positioning of the oocyte. Development. 1998;125:3635–3644. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.18.3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieder NC, de Cuevas M, Spradling AC. The fusome organizes the microtubule network during oocyte differentiation in Drosophila. Development. 2000;127:4253–4264. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachet O, Ephrussi A. Drosophila Y14 shuttles to the posterior of the oocyte and is required for oskar mRNA transport. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:1666–1674. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00508-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong A, Lee-Kong S, Iida T, Sugimura I, Lilly MA. The p27cip/kip ortholog dacapo maintains the Drosophila oocyte in prophase of meiosis I. Development. 2003;130:1235–1242. doi: 10.1242/dev.00352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenraad CC, Akhmanova A, Howell SA, Dortland BR, De Zeeuw CI, Willemsen R, Visser P, Grosveld F, Galjart N. Mammalian Golgi-associated Bicaudal-D2 functions in the dynein-dynactin pathway by interacting with these complexes. EMBO J. 2001;20:4041–4054. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenraad CC, Wulf P, Schiefermeier N, Stepanova T, Galjart N, Small JV, Grosveld F, de Zeeuw CI, Akhmanova A. Bicaudal D induces selective dynein-mediated microtubule minus end-directed transport. EMBO J. 2003;22:6004–6015. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh J, St Johnston D. The role of BicD, egl, orb and the microtubules in the restriction of meiosis to the Drosophila oocyte. Development. 2000;127:2785–2794. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.13.2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh JR, Shulman JM, Benton R, St Johnston D. PAR-1 is required for the maintenance of oocyte fate in Drosophila. Development. 2001;128:1201–1209. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh JR, St Johnston D. The origin of asymmetry: early polarisation of the Drosophila germline cyst and oocyte. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:R438–R449. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauch R, Bourenkov GP, Chung HR, Urlaub H, Reidt U, Jackle H, Wahl MC. The zinc finger-associated domain of the Drosophila transcription factor grauzone is a novel zinc-coordinating protein-protein interaction module. Structure. 2003;11:1393–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce EF, McKim KS. Drosophila PCH2 is required for a pachytene checkpoint that monitors double-strand-break-independent events leading to meiotic crossover formation. Genet. 2009;181:39–51. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.093112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakesisoglou I, Yang Y, Fuchs E. An epidermal plakin that integrates actin and microtubule networks at cellular junctions. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:195–208. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi S, Zheng Y. Characterization of a Drosophila centrosome protein CP309 that shares homology with Kendrin and CG-NAP. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:37–45. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-03-0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RC. Ovarian Development in Drosophila melanogaster. Academic Press; New York: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Klymkowsky MW, Karnovsky A. Morphogenesis and the cytoskeleton: studies of the Xenopus embryo. Dev. Biol. 1994;165:372–384. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laity JH, Lee BM, Wright PE. Zinc finger proteins: new insights into structural and functional diversity. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz V, Chang JS, Horabin JI, Bopp D, Schedl P. The Drosophila orb RNA-binding protein is required for the formation of the egg chamber and establishment of polarity. Genes Dev. 1994;8:598–613. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.5.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Hir H, Andersen GR. Structural insights into the exon junction complex. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Hir H, Izaurralde E, Maquat LE, Moore MJ. The spliceosome deposits multiple proteins 20-24 nucleotides upstream of mRNA exon-exon junctions. EMBO J. 2000;19:6860–6869. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Kolodziej PA. Short Stop provides an essential link between F-actin and microtubules during axon extension. Development. 2002;129:1195–1204. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.5.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lespinet O, Wolf YI, Koonin EV, Aravind L. The role of lineage-specific gene family expansion in the evolution of eukaryotes. Genome Res. 2002;12:1048–1059. doi: 10.1101/gr.174302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly MA, Spradling AC. The Drosophila endocycle is controlled by cyclin E and lacks a checkpoint ensuring S-phase completion. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2514–2526. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Spradling AC. Fusome asymmetry and oocyte determination in Drosophila. Dev. Genet. 1995;16:6–12. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020160104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HF, Yue L, Spradling AC. The Drosophila fusome, a germline-specific organelle, contains membrane skeletal proteins and functions in cyst formation. Development. 1994;120:947–956. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Xie T, Steward R. Lis1, the Drosophila homolog of a human lissencephaly disease gene, is required for germline cell division and oocyte differentiation. Development. 1999;126:4477–4488. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mach JM, Lehmann R. An Egalitarian-BicaudalD complex is essential for oocyte specification and axis determination in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1997;11:423–435. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahowald AP, Strassheim JM. Intercellular migration of centrioles in the germarium of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Biol. 1970;45:306–320. doi: 10.1083/jcb.45.2.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Campos M, Basto R, Baker J, Kernan M, Raff JW. The Drosophila pericentrin-like protein is essential for cilia/flagella function, but appears to be dispensable for mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 2004;165:673–683. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200402130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matanis T, Akhmanova A, Wulf P, Del Nery E, Weide T, Stepanova T, Galjart N, Grosveld F, Goud B, De Zeeuw CI, Barnekow A, Hoogenraad CC. Bicaudal-D regulates COPI-independent Golgi-ER transport by recruiting the dynein-dynactin motor complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:986–992. doi: 10.1038/ncb891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Máthé E, Inoue YH, Palframan W, Brown G, Glover DM. Orbit/Mast, the CLASP orthologue of Drosophila, is required for asymmetric stem cell and cystocyte divisions and development of the polarised microtubule network that interconnects oocyte and nurse cells during oogenesis. Development. 2003;130:901–915. doi: 10.1242/dev.00315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrail M, Hays TS. The microtubule motor cytoplasmic dynein is required for spindle orientation during germline cell divisions and oocyte differentiation in Drosophila. Development. 1997;124:2409–2419. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.12.2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKim KS, Hayashi-Hagihara A. mei-W68 in Drosophila melanogaster encodes a Spo11 homolog: evidence that the mechanism for initiating meiotic recombination is conserved. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2932–2942. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micklem DR, Dasgupta R, Elliot H, Gergely F, Davidson C, Brand A, González-Reyes A, St. Johnston D. The mago nashi gene is required for the polarisation of the oocyte and the formation of perpendicular axes in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:468–478. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr SE, Dillon ST, Boswell RE. The RNA-binding protein Tsunagi interacts with Mago Nashi to establish polarity and localize oskar mRNA during Drosophila oogenesis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2886–2899. doi: 10.1101/gad.927001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro C, Puthalakath H, Adams JM, Strasser A, Lehmann R. Egalitarian binds dynein light chain to establish oocyte polarity and maintain oocyte fate. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:427–435. doi: 10.1038/ncb1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark PA, Mohr SE, Gong L, Boswell RE. mago nashi mediates the posterior follicle cell-to-oocyte signal to organize axis formation in Drosophila. Development. 1997;124:3197–3207. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.16.3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop PD, Sutasurya LA. Primordial Germ Cells in Chordates. Cambridge University Press; London: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop PD, Sutasurya LA. Primordial Germ Cells in the Invertebrates. Cambridge University Press; London: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Page SL, Hawley RS. c(3)G encodes a Drosophila synaptonemal complex protein. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3130–3143. doi: 10.1101/gad.935001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios IM, Gatfield D, St Johnston D, Izaurralde E. An eIF4AIII-containing complex required for mRNA localization and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Nature. 2004;427:753–757. doi: 10.1038/nature02351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks AL, Cook KR, Belvin M, Dompe NA, Fawcett R, Huppert K, Tan LR, Winter CG, Bogart KP, Deal JE, Deal-Herr ME, Grant D, Marcinko M, Miyazaki WY, Robertson S, Shaw KJ, Tabios M, Vysotskaia V, Zhao L, Andrade RS, Edgar KA, Howie E, Killpack K, Milash B, Norton A, Thao D, Whittaker K, Winner MA, Friedman L, Margolis J, Singer MA, Kopczynski C, Curtis D, Kaufman TC, Plowman GD, Duyk G, Francis-Lang HL. Systematic generation of high-resolution deletion coverage of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:288–292. doi: 10.1038/ng1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parma DH, Bennett PE, Jr., Boswell RE. Mago Nashi and Tsunagi/Y14, respectively, regulate Drosophila germline stem cell differentiation and oocyte specification. Dev. Biol. 2007;308:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]