Abstract

ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) is required for the lipidation of apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I), although molecular mechanisms supporting this process remain poorly defined. In this study, we focused on the role of cytosolic Ca2+ and its signaling and found that cytosolic Ca2+ was required for cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. Removing extracellular Ca2+ or chelating cytosolic Ca2+ were equally inhibitory for apoA-I lipidation. We provide evidence that apoA-I induced Ca2+ influx from the medium. We further demonstrate that calcineurin activity, the downstream target of Ca2+ influx, was essential; inhibition of calcineurin activity by cyclosporine A or FK506 completely abolished apoA-I lipidation. Furthermore, calcineurin inhibition abolished apoA-I binding and diminished JAK2 phosphorylation, an established signaling event for cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. Finally, we demonstrate that neither Ca2+ manipulation nor calcineurin inhibition influenced ABCA1's capacity to release microparticles or to remodel the plasma membrane. We conclude that this Ca2+-dependent calcineurin/JAK2 pathway is specifically responsible for apoA-I lipidation without directly modifying ABCA1 activity.

Keywords: macrophage, cyclosporine A, Janus Kinase 2

ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) belongs to a large family of evolutionarily conserved transmembrane proteins that transport a wide variety of substrates across the plasma membrane, including ions, drugs, peptides, and lipids. In particular, ABCA1 is a member of the ABC-A subfamily, of which many members transport lipids in multicellular organisms (1). ABCA1 is required to transfer cellular cholesterol to apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I), leading to the production of HDL. The molecular details of how ABCA1 and apoA-I interact to induce lipidation are largely unknown. In vitro, either lipid-free or lipid-poor apoA-I can induce rapid efflux of both cholesterol and phospholipid from all cell types that express ABCA1. Also, plasma membrane expression of ABCA1 is positively correlated with lipid-free apoA-I association with cells. ABCA1 dysfunctional mutations, which occur in Tangier disease, abolish cholesterol efflux and the cell association of lipid-free apoA-I, clinically resulting in low HDL levels in the circulation (2).

Recent studies have implicated many signaling proteins in ABCA1 function and apoA-I lipidation. For example, no less than 10 kinase pathways have been proposed to modulate posttranslational ABCA1 activity (3–10). The key signaling molecules in these kinase pathways include protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase C (PKC), Cdc42, protein kinase 2 (CK2), and Janus Kinase 2 (JAK2). Among these pathways, apoA-I has frequently been implicated as the candidate to initiate signaling processes required for cholesterol efflux. Although several possible mechanisms have been suggested, a clear consensus on which pathway acts as the critical regulator of apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux is still lacking.

Takahashi and Smith (11) reported that extracellular Ca2+ was required for cellular association with apoA-I and apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux. It was proposed that Ca2+ was acting as a structural requirement for apoA-I to bind to cell surface receptors, not entirely dissimilar to LDL binding to the LDL receptor (12). Curiously, Ca2+ is the most ubiquitous and pluripotent signaling molecule and a well-known second messenger that can initiate a diverse array of intracellular signaling events across different spatial and temporal domains. In resting cells, the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration is maintained at low levels (100 nM) relative to the extracellular medium (1–2 mM). This enables cells to rapidly increase cytosolic Ca2+ levels through Ca2+ influx, often in conjunction with Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. The rise in cytosolic Ca2+ then triggers Ca2+ binding to regulatory proteins, such as calmodulin (CaM). Upon binding of Ca2+, CaM undergoes a conformational change that drastically increases its binding affinity for a wide array of downstream target proteins (13). Many target proteins of CaM are kinases or phosphatases; these include myosin light chain kinase, CaM-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) I, II, and IV, and calcineurin.

In light of an early study that documented enhanced anion flux in ABCA1-expressing Xenopus oocytes (14), we attempted to determine whether Ca2+, particularly Ca2+ influx, plays an intracellular role in facilitating apoA-I lipidation through signaling events. We found that, in both BHK cells and RAW macrophages, cytosolic Ca2+ was required for cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. We provide evidence that apoA-I induced Ca2+ influx into cells. We further demonstrate that calcineurin signaling, the downstream target of Ca2+ influx and CaM activation, was also essential for ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. Furthermore, inhibition of calcineurin interfered with JAK2 phosphorylation, an established signaling event for cholesterol efflux to apoA-I, and abolished apoA-I binding. Finally, we demonstrated that neither Ca2+ manipulations nor calcineurin inhibition affected ABCA1 expression, cellular distribution, basal cholesterol efflux, or its ability to remodel the plasma membrane. The Ca2+-dependent CaM/calcineurin/JAK2 pathway is therefore specifically responsible for apoA-I lipidation without directly modifying ABCA1 activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and reagents

Cell culture growth media, antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin), and fetal calf serum (FCS) were purchased from Invitrogen. BHK cells were the generous gift from Drs. Oram and Vaughan (University of Washington, Seattle). These cells carry a mifepristone inducible vector with or without an ABCA1 gene insert. The RAW 264.7 cell line was purchased from the ATCC. Mifepristone was from Invitrogen, and 8-Br-cAMP from Sigma-Aldrich. Ca2+-free DMEM medium (cat no. 21068) was purchased from Invitrogen, which contains all the components of normal DMEM including Mg2+ except no Ca2+. The following antibodies were acquired from several vendors: rabbit polyclonal anti-ABCA1 (Novus Biological Inc.), Alexa Fluo 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes), Ecl anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase linked whole antibody from donkey (GE Healthcare), anti-JAK2 rabbit polyclonal IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), and rabbit polyclonal anti-phosphorylated-JAK2 [pYpY1007/1008] (Invitrogen). Our protease inhibitor cocktail was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The following chelators and modulators of ion flux were purchased from a variety of sources: 4,4'-diisothiocyano-2,2'-stilbene disulphonic acid hydrate disodium salt (DIDS; Sigma-Aldrich), sodium thiocyanate (Sigma-Aldrich), sodium gluconate (Sigma-Aldrich), EDTA (Fisher Scientific), EGTA (Fisher Scientific), thapsigargin (Calbiochem), ryanodine (Tocris Bioscience), 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate (2-APB; Sigma), and BAY-K8644 (Alexis Biochemicals). The pharmacological inhibitors of cellular signaling pathways were from the following vendors: W-7 hydrochloride (Calbiochem), cyclosporine A (CsA; Sigma-Aldrich), FK506 (A.G. Scientific), and PKI (Calbiochem). The two phosphatase inhibitors, sodium fluoride (NaF) and sodium vanadate (NaVO4), were purchased from Fisher Scientific. The Cy2 bis-reactive dye and the ECL Western blotting system were from GE Healthcare. [45Calcium] was from GE Healthcare, and cholesterol, [1,2-3H(N)]cholesterol was from Perkin Elmer. Human apoA-I was acquired from Biodesign international.

Cell cultures

Both baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells and RAW 267.4 macrophage cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. ABCA1 expression was induced during 16–18 h incubation in DMEM with 1 mg/ml BSA, which included either 5 nM mifepristone or 250 μM 8-Br-cAMP, for BHK and RAW cells, respectively. Mock-transfected cells were used as negative controls in experiments with BHK cells, whereas 8-Br-cAMP was withheld for negative controls in experiments with RAW cells.

Cy2-apoA-I cell surface association

Purified apoA-I was conjugated to the Cy2 fluorophore according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, apoA-I was dialyzed with 0.1 M Na2CO3, pH 9.5, and then combined with the Cy2 bis-reactive reagent. Following conjugation, labeled Cy2-apoA-I was separated from unlabeled dye on a P10 BioGel column (Bio-Rad). The concentration of Cy2-apoA-I was determined using the Lowry protein assay. Cy2-apoA-I (5 μg/ml) was incubated with cells for 2 h at 37°C to determine cell association. During each experiment, cells were preincubated with different exogenous compounds for 15 min before the addition of Cy2-apoA-I. After the incubation period (2 h), adherent cells were detached from the plate surface using 4 mM EGTA and 4 mM EDTA in PBS (the use of trypsin was avoided to prevent digestion of surface proteins that may be required for apoA-I cell association). In RAW cells, the cells were suspended before the 2 h treatment, because induction with 8-Br-cAMP reduces the adherence of RAW cells. Finally, degree of Cy2-apoA-I cell association was determined by flow cytometry. The amount of Cy2-apoA-I association was expressed relative to negative and positive (ABCA1-expressing) controls. Similarly treated cells were also incubated with Cy2-apoA-I on ice for 2 h and Cy2-apoA-I binding was assessed by flow cytometry.

Cholesterol efflux

BHK and RAW 264.7 cells were grown with 1 µCi/ml [1,2-3H(N)]cholesterol with DMEM/10% FCS for 2 days to label cells to equilibrium. After 2 days, the growth medium was replaced with DMEM + 1 mg/ml BSA. ABCA1 expression was induced with either 5 nM mifepristone or 250 μM 8-Br-cAMP, as indicated above. After expression of ABCA1 (16–18 h), the growth medium was replaced with fresh DMEM + 1 mg/ml BSA to act as the efflux assay medium. A variety of modulators were included in the medium for 2 or 4 h to measure their effects on cholesterol efflux. During apoA-I-dependent efflux, apoA-I (5 μg/ml) was included in the efflux medium. After the duration of the efflux (2 or 4 h), medium was collected and centrifuged at 500 × g to remove cell debris. The cell-free supernatant was then combined with scintillation liquid and total counts per minute (cpm) were measured. The remaining adherent cells were lysed in 0.5 N NaOH, and the total cpm of the lysate was measured. Cholesterol efflux was expressed as the ratio between the cpm from the efflux medium and the total cpm found in the cell lysate and efflux medium. In some experiments, cholesterol efflux was expressed as a percentage relative to the negative controls (without apoA-I) and positive controls (with apoA-I alone).

Immunofluorescent staining

BHK cells were plated and grown in glass-coverslip-bottom microscopy dishes to 50–70% confluency. Cells were washed with PBS then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min, followed by permeabilization with 0.1 mg/ml saponin in PBS for 30 min. Cells were blocked with 5% calf serum and 50 mM NH4Cl in PBS for 20 min. The primary ABCA1-specific antibody was then added at a concentration of 1:500 in a solution of 5% calf serum/PBS for 30 min. After washing with PBS and incubating with 5% calf serum/PBS for 20 min, secondary antibody (Alexa Fluo 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG) was then added at a concentration of 1:200 for 30 min, followed by a 45 min incubation in 5% calf serum/PBS. The cellular localization of immunofluorescence was observed and recorded using a C1 confocal module on a Nikon TE2000-E inverted fluorescent microscope with a 60× objective. Images from ABCA1 and mock cells were taken using identical settings.

45Ca influx into BHK cells

BHK cells were grown to approximately 75% confluency in 24-well plates. The culture plates were placed in a 37°C water bath and incubated in 500 μl of prewarmed DMEM + 1 mg/ml BSA for 5 min. In some of wells, 5 μg/ml apoA-I was included in the medium. DMEM (50 μl) with 55 μCi/μl [45Ca] was then added to triplicate wells for 4 min. Immediately after 4 min incubation, cells were washed with ice cold DMEM + 5 mM EGTA to stop channel activity and remove surface bound [45Ca]. Cells were lysed with 0.5 N NaOH and the total cell associated 45Ca cpm was measured using a β-counter to determine the total cellular influx of [45Ca]. To determine the amount of nonspecific [45Ca] association with cells, the same experiments were carried out in ice-cold buffers to prevent channel activity. This nonspecific association was subtracted from the total cell associated cpm to produce values for 45Ca influx. Finally, the total protein content of each well was determined using the Lowry assay and all values were presented as a ratio of [45Ca] cpm/μg protein.

Methylthiazol tetrazolium assay

After overnight induction with various concentrations of mifepristone, BHK cells in 12-well dishes were rinsed and returned to DMEM + 10% FCS before treating with various reagents for 2 h. Then 20 μl of methylthiazol tetrazolium (MTT) solution (5 mg/ml) was added directly into each well. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Medium was carefully removed with a syringe to avoid disturbing formazan crystals formed during the incubation. DMSO (100 μl) was added to dissolve the crystals. The absorbance was then measured at 550 nm.

Statistics

Statistical comparisons between groups were performed with PRISM software (GraphPad). Data are mostly presented as mean ± SD. The statistical significance of differences between groups was analyzed by Student's t-test. Differences were considered significant at a P-value < 0.05.

RESULTS

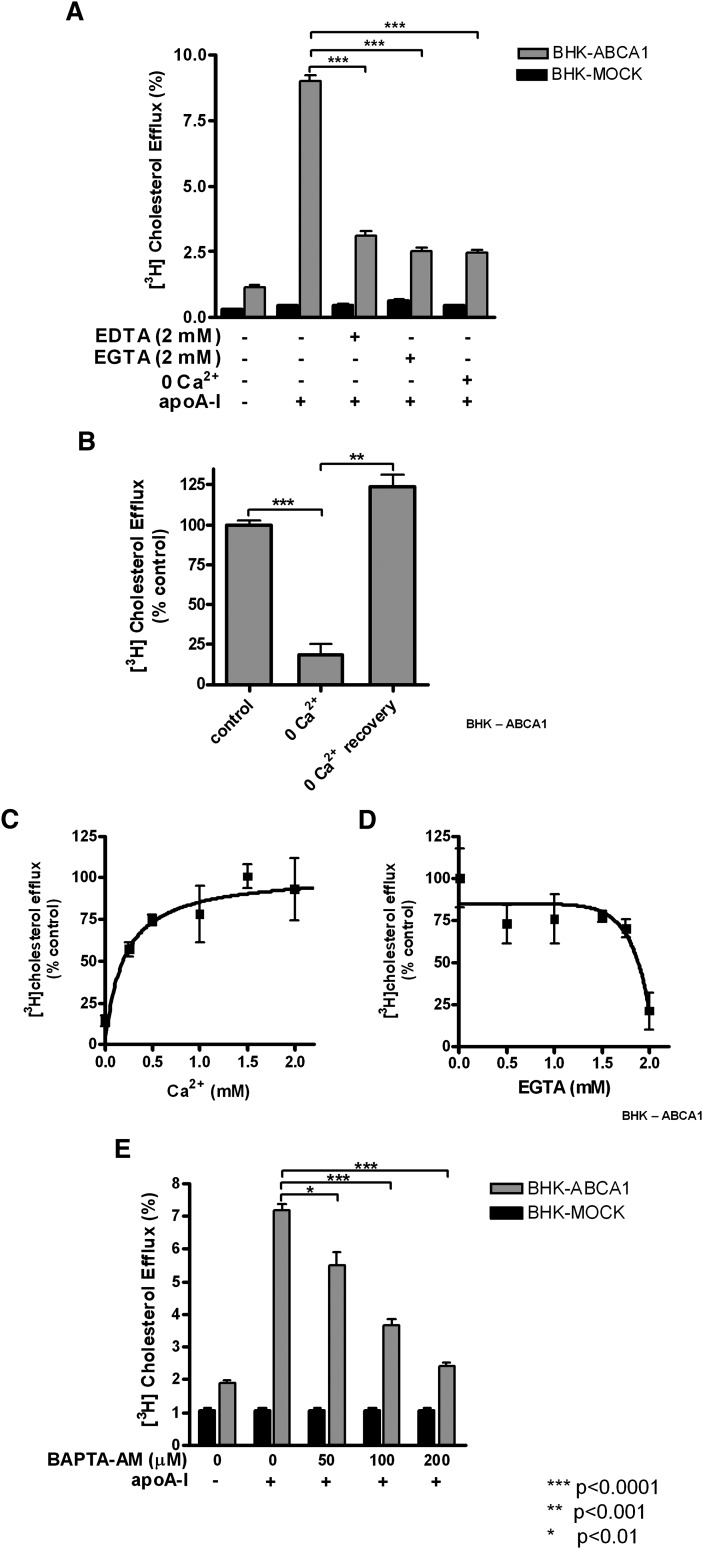

An early study revealed that ABCA1 expression on the plasma membrane of Xenopus oocytes increases anion flux (14). Also, Smith et al. (11) reported that extracellular Ca2+ is required for apoA-I lipidation. Thus, we were interested in potential intracellular Ca2+ signaling in cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. Extracellular Ca2+ was removed by adding Ca2+ chelators to the medium or using Ca2+-free medium during cholesterol efflux. EDTA broadly chelates divalent cations (i.e. Mg2+ and Ca2+), whereas EGTA is much more specific for Ca2+. Both molecules caused a drastic reduction in cholesterol efflux, although EGTA was more effective (80% inhibition) (Fig. 1A). Efflux was similarly inhibited when Ca2+-free medium was used (Fig. 1A). The Ca2+-free medium used here (DMEM 21068, Invitrogen) contains normal concentration of Mg2+, indicating that the effect of EGTA is specific for Ca2+. Also, the inhibition can be readily relieved as soon as a normal amount of Ca2+ (1.8 mM) is reintroduced to the medium (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effect of Ca2+ on ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux to apoA-I in ABCA1-expressing BHK cells. ABCA1 and mock BHK cells were labeled with [3H]cholesterol for 1–2 days and induced with 5 μM mifepristone overnight. Cholesterol efflux to apoA-I (5 μg/ml) was measured under the following conditions. A: Extracellular Ca2+ was removed using the cation chelator EDTA or the Ca2+-specific chelator EGTA. Cholesterol efflux was also measured in Ca2+-free medium. B: Cells were incubated in Ca2+-free medium for 2 h and then switched back to normal medium containing Ca2+. C, D: The dose dependency of extracellular or intracellular Ca2+ on efflux was determined by increasing medium Ca2+ (C) or EGTA (D) concentrations. E: Cells were treated with increasing doses of BAPTA-AM. Both medium and cell associated 3H radioactivity were counted and presented as percentage of cholesterol in the medium relative to the total cholesterol (medium and cell-associated). In B, cholesterol efflux was presented as a percentage relative to untreated cells (control). Data is presented as mean ± SD of triplicate wells, representative of at least three experiments performed.

We also characterized the dose-dependence relationship between extracellular Ca2+ concentrations and cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. We found that the Ca2+ concentration required for half maximal efflux was approximately 200 μM (Fig. 1C). It is particularly interesting that this value is relatively small compared with the normal extracellular concentration of 1.8 mM, suggesting that only a very low concentration of extracellular calcium is necessary for cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. A similar trend was observed when EGTA was supplemented into the growth medium at increasing concentrations (Fig. 1D); the efficacy of cholesterol efflux was only dramatically affected at high concentrations of EGTA (>1.75 mM), as it chelates almost all Ca2+ ions. Together, these findings confirm the importance of extracellular calcium during efflux to apoA-I, as previously observed by Smith et al. (11).

Although removing extracellular Ca2+ could influence protein-protein interaction at the cell surface or endocytosis (11), it also eliminates Ca2+ influx, a key event for many intracellular signaling processes. To test whether intracellular Ca2+ is specifically required, ABCA1-expressing BHK cells were preloaded with increasing concentrations of BAPTA-AM (0–200 μM) for 15 min. BAPTA-AM is a membrane permeable precursor of a Ca2+ chelator that does not bind Ca2+ in its native form. However, once inside cells, the AM ester is hydrolyzed by esterases, which traps BAPTA inside cells and also enables BAPTA to chelate Ca2+. BAPTA-AM, therefore, provides a means to specifically buffer intracellular Ca2+ without compromising extracellular Ca2+ levels. We found that BAPTA-AM abolished cholesterol efflux in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1E). Significantly, cholesterol efflux was completely inhibited at the highest concentration of BAPTA-AM (200 μM) used. Cells remained viable under these conditions (not shown). Also, by increasing the extracellular Ca2+ concentration (thus increasing Ca2+ influx), we could partially rescue the cholesterol efflux from BAPTA-AM treated cells (data not shown). This demonstrates for the first time that intracellular Ca2+ is critically required for ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. It also implies that removing extracellular Ca2+ most likely affects intracellular Ca2+ levels, thus altering cholesterol efflux.

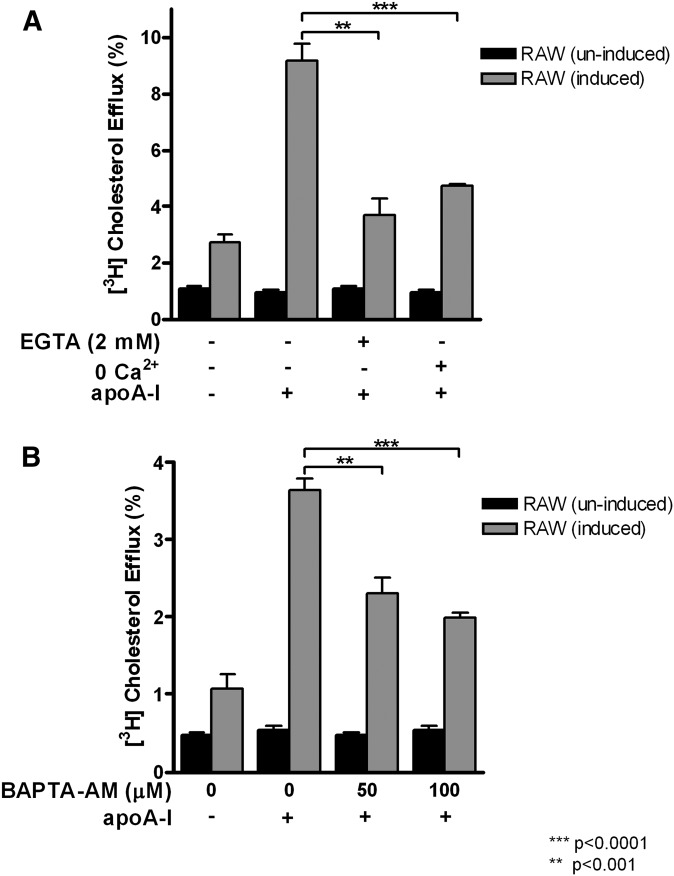

Importantly, we found that ABCA1-expressing RAW macrophages also require Ca2+ in cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. Cholesterol efflux from these macrophages shared the same sensitivity to EGTA and Ca2+ free condition (Fig. 2A) or to BAPTA-AM (Fig. 2B). The minimal requirement for extracellular Ca2+ was also in the low-micromolar range, similar to what was observed in BHK cells (data not shown). These results suggest that Ca2+, particularly intracellular Ca2+, is a common factor required for cholesterol efflux to apoA-I, regardless of cell types.

Fig. 2.

Effect of intracellular and extracelluar Ca2+ on cholesterol efflux to apoA-I in RAW macrophages. RAW macrophages were induced to express ABCA1 with 250 μM Br-cAMP or uninduced overnight. Cholesterol efflux was analyzed under following conditions: 2 mM EGTA or 0 Ca2+ (A); 50 μM and 100 μM BAPTA-AM (B). Data is presented as mean ± SD of triplicate wells, representative of at least three experiments performed.

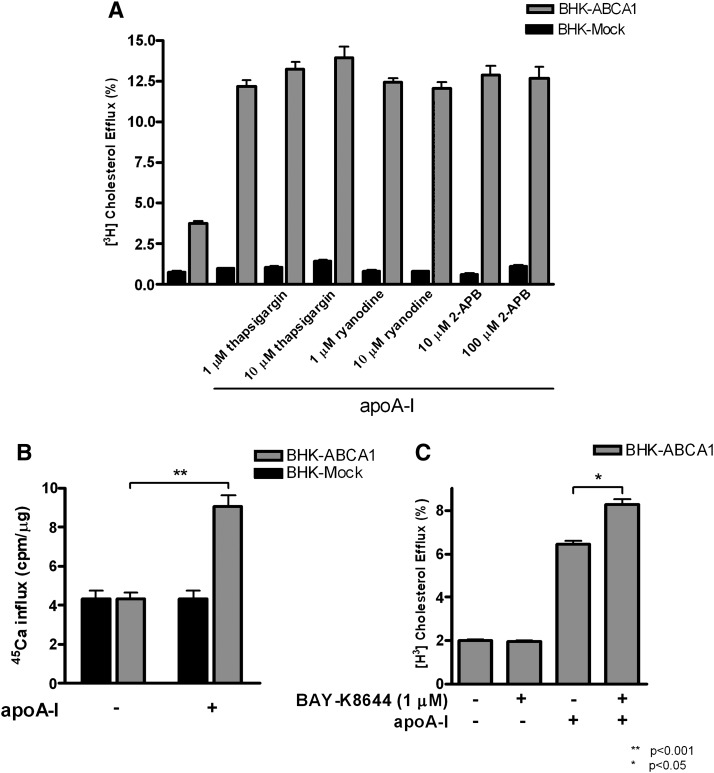

Together, the above results suggest that cholesterol efflux to apoA-I requires Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane and consequently induces a rise in cytosolic Ca2+. Alternatively, such a rise could be initiated by Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores. The sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) is a Ca2+ pump that loads the ER in an ATP-dependent manner, whereas the ryanodine receptor (RyR) and the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate-gated Ca2+ release channel (InsP3R) control the release of Ca2+ from the ER. Thus, we used thapsigargin as a specific inhibitor of the SERCA pump. Thapsigargin binds SERCA irreversibly and prevents refilling of the ER with Ca2+. Under this condition, the ER cannot be replenished with Ca2+ after it is released through the RyR and InsP3R channels. Therefore, thapsigargin inhibits the contribution of ER stores to the cytoplasmic pool of Ca2+. We found that cholesterol efflux to apoA-I was not inhibited by thapsigargin at concentrations (100 nM to 10 μM) effectively used by others (15–18) (Fig. 3A). Ryanodine and 2-APB, which inhibit RyR and InsP3R, respectively, also did not inhibit cholesterol efflux to apoA-I at well-established inhibitory concentrations (19, 20) (Fig. 3A). Combinations of thapsigargin, ryanodine, and/or 2-APB were also tested with no measurable effects (data not shown). Therefore, we conclude that ER Ca2+ stores did not contribute to the intracellular BAPTA-sensitive pool of Ca2+ that participates in ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. The BAPTA-sensitive pool of Ca2+ most likely comes from the extracellular medium.

Fig. 3.

Effect of Ca2+ flux from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stores and across the plasma membrane on cholesterol efflux to apoA-I in ABCA1-expressing BHK cells. ABCA1 and Mock BHK cells were labeled with [3H]cholesterol and induced with mifepristone overnight. Cholesterol efflux to apoA-I (5 μg/ml) was measured under the following conditions. A: Cells were treated with indicated concentrations of thapsigargin, ryanodine, and 2-APB, respectively. B: The amount of radiolabeled [45Ca2+] influx into cells was determined in mock and ABCA1-expressing cells with or without the presence of 10 μg/ml apoA-I over 4 min. C: The effect of a Ca2+ channel agonist, BAY-K8644, on cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. The results in each graph show the mean ± SD of triplicate wells, representative of at least three experiments performed.

We next tested whether apoA-I stimulates Ca2+ influx from the extracellular medium. We initially attempted to measure changes in intracellular free Ca2+ using the cell permeable fluorescent probe, Fura 2-AM, but did not detect any significant changes in intracellular free Ca2+ (supplementary Fig. I). We took this as a sign that the magnitude of Ca2+ influx triggered by apoA-I could be relatively low such that fluorescent probes may not be sensitive enough to detect it. Consequently, we resorted to a highly sensitive 45Ca2+ method to analyze the net influx of Ca2+ into the cells from the extracellular medium. In these experiments, cells were briefly exposed to 45Ca2+ containing medium either in the presence or in the absence of apoA-I. The short duration of 45Ca2+ pulse was to ensure that Ca2+ efflux does not significantly contribute to the analysis (21). Also, extra care was taken to strip off Ca2+ bound on the cell surface to ensure true measurement of Ca2+ influx to the cytoplasm. Specifically, the net 45Ca2+ influx was measured by cell-associated 45Ca2+ radioactivity after 4 min incubation in the medium containing 45Ca2+. We found that 45Ca2+ influx into ABCA1-expressing BHK cells was nearly doubled in the presence of apoA-I, whereas apoA-I did not alter 45Ca2+ influx in mock-BHK cells (Fig. 3B). This demonstrates that apoA-I induced Ca2+ influx in ABCA1-expressing cells. Such Ca2+ influx from the extracellular medium could be critical for cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. To test this, we used BAY-K8644, an agonist of plasma membrane L-type Ca2+ channels (22), to further increase Ca2+ influx. BAY-K8644 (1 μM) was indeed able to increase cholesterol efflux to apoA-I by 35% (Fig. 3C). Together, these findings demonstrate that apoA-I stimulates Ca2+ influx in ABCA1-expressing cells. This influx likely initiates intracellular signaling events required for cholesterol efflux to apoA-I.

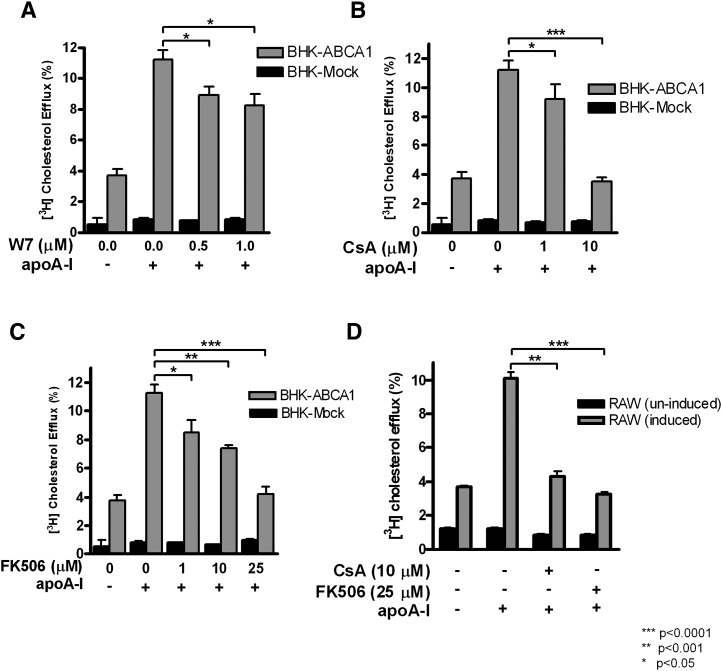

We next looked into the potential target of intracellular Ca2+ in the process of cholesterol efflux. Intracellular Ca2+ is commonly employed as a second messenger to regulate a variety of signaling pathways (23). For example, CaM is the primary target of Ca2+ signaling in eukaryotic cells (23). We therefore first examined whether CaM is involved in cholesterol efflux process. Cells were treated with W-7 during cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. W-7 is a CaM antagonist and prevents the binding of Ca2+-bound CaM with its downstream substrates (24). W-7 indeed caused a significant inhibition of cholesterol efflux to apoA-I at relative low concentrations (0.5 and 1 μM) (Fig. 4A). Both BHK cells and macrophages were highly sensitive to W-7, which prevented us from testing the effect of higher W-7 concentrations.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of CaM and calcineurin reduces cholesterol efflux to apoA-I in ABCA1-expressing cells. BHK cells and RAW macrophages were induced with mifepristone or Br-cAMP, respectively. Cholesterol efflux to apoA-I (5 μg/ml) was measured under the following conditions: the indicated concentrations of the CaM inhibitor, W-7 (A); calcineurin inhibitors CsA (B) and FK506 (C). D: CsA and FK506 were also used with RAW macrophages expressing ABCA1. The results in each graph show the mean ± SD of triplicate wells, representative of at least three experiments performed.

Activation of CaM by Ca2+ is known to modulate the function of various downstream targets, including CaMKII, myosin light chain kinase, and calcineurin (23). Although CaM is a relatively abundant protein, the pool of free CaM is limited due to a wide range of CaM targets in cells. There is likely intense competition among CaM targets for the Ca2+-CaM complex, and the action of these targets may be at least partially determined by their respective affinity to Ca2+-CaM (25). Among these targets, calcineurin has the highest affinities to Ca2+-CaM [dissociation constant (Kd) = ∼0.1 nM] (26) and therefore should be most sensitive to Ca2+ fluctuations or CaM activation. Given our observation described above that Ca2+ influx triggered by apoA-I is of low amplitude (thus could not be detected by Fura-2), we considered calcineurin as a likely candidate in cholesterol efflux to apoAI. Interestingly, earlier studies reported that CsA abrogates ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux (27, 28). Best known as an immune-suppressor in vivo, CsA mechanistically inhibits calcineurin by forming a complex with cyclophilins, the effector protein of calcineurin (29). When CsA was included in the medium with apoA-I, cholesterol efflux to apoA-I was potently inhibited with complete inhibition at 10 μM (Fig. 4B). To further verify the specificity of CsA on calcineurin, we used another unrelated specific calcineurin inhibitor, FK506. FK506 binds to FKBP12, another effector protein that interacts with calcineurin at a slightly different site from that of cyclophilins (30). Fig. 4C shows that FK506 also functioned as a potent inhibitor. Cholesterol efflux to apoA-I was dose dependently inhibited and was completely abolished at 25 μM of FK506. Moreover, both CsA and FK506 were equally efficient at inhibiting efflux to apoA-I in RAW cells (Fig. 4D). Thus, by using two highly specific calcineurin inhibitors that are structurally and mechanistically distinct, we conclude that the Ca2+-dependent CaM/calcineurin signaling pathway is essential for cholesterol efflux to apoA-I.

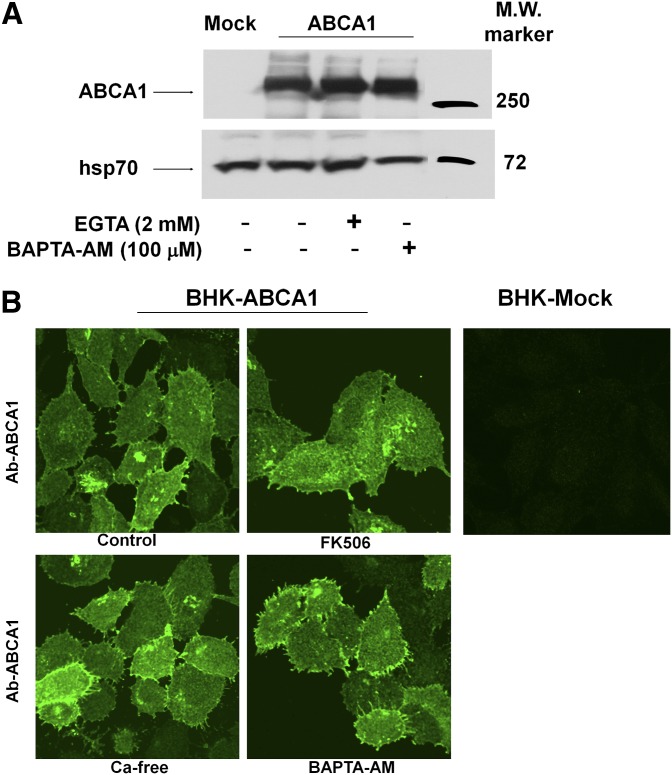

The CaM/calcineurin signaling pathway is known to activate nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) to initiate gene regulations (23). Because all the experiments reported here were performed within 2 h, gene regulation is not likely to be a significant factor. We nevertheless wanted to rule out the possibility of ABCA1 downregulation. We found that ABCA1 protein expression levels and cellular distribution remained unchanged after Ca2+ manipulation or calcineurin inhibition (Fig. 5A, B). This is largely consistent with an earlier conclusion made by Smith et al. (11, 27) that inhibition of cholesterol efflux to apoA-I by either Ca removal or CsA is not due to ABCA1 downregulation. However, we did not detect increased ABCA1 expression as observed by earlier studies (11, 27), which could be due to the short duration of our experiments (2 h vs. 4 h) or cell type differences.

Fig. 5.

Altering intracellular or extracelluar Ca2+ distribution had no effect on ABCA1 expression or localization. A: The level of ABCA1 protein expression in BHK cells was determined by immunoblotting after 2 h incubation with EGTA or BAPTA-AM. B: Immunofluorescent detection of ABCA1 in mock and ABCA1-expressing cells BHK cells under different Ca2+ treatment conditions. Images were taken using a confocal fluorescent microscope focused on the plasma membrane and displayed identically.

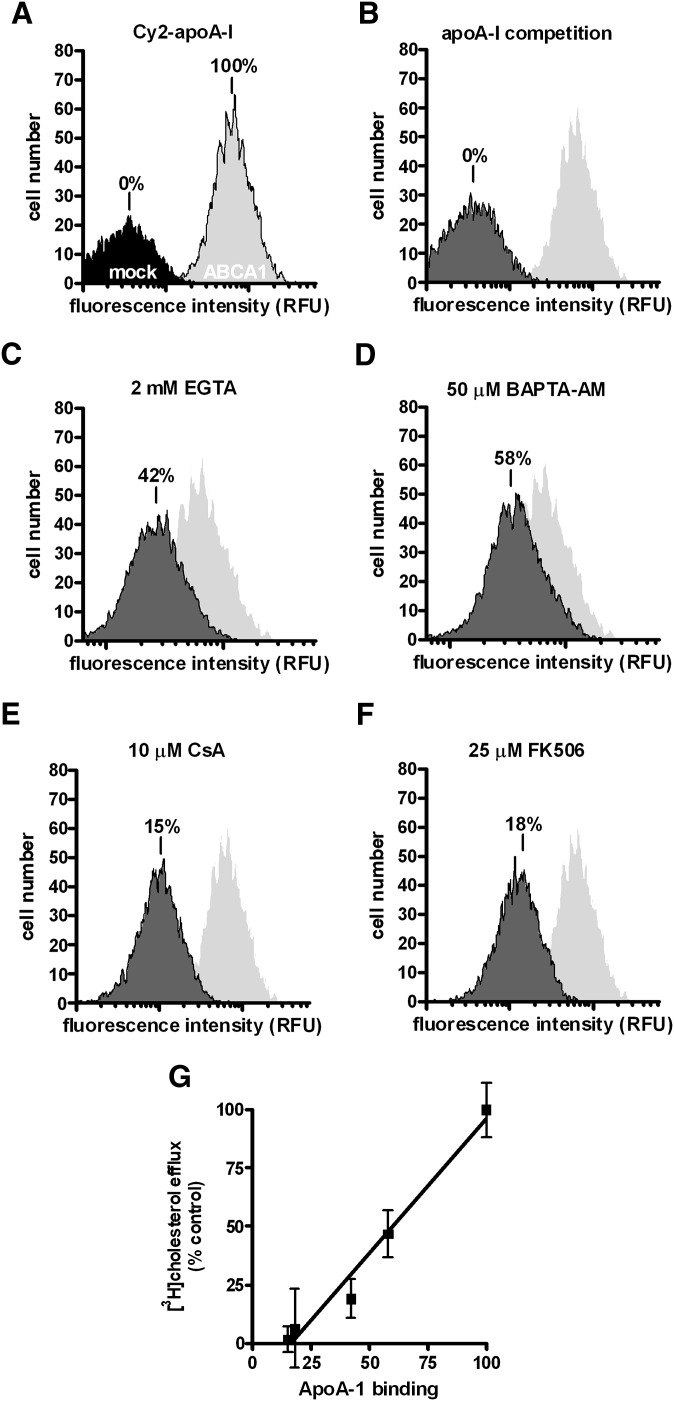

The successful lipidation of apoA-I is known to require prolonged interaction between plasma membrane and apoA-I, which generates a measurable apoA-I association with cells. We therefore examined whether apoA-I cell association was affected. This was achieved by flow cytometry detection of fluorescent-labeled apoA-I (Cy2-apoA-I). Cy2-apoA-I retained its potency in inducing cholesterol efflux as native apoA-I (data not shown). As expected, ABCA1 expression induced high levels of apoA-I cell association, whereas Cy2-apoA-I did not significantly bind mock-BHK cells (Fig. 6A). Excess unlabeled apoA-I completely abrogated Cy2-apoAI binding to ABCA1-expressing cells (Fig. 6B), further confirming the specificity of Cy2-apoA-I. We found that EGTA (2 mM) significantly reduced Cy2-apoA-I cell association to 42% relative to cells bathed in normal Ca2+ medium (Fig. 6C). The addition of 50 μM BAPTA-AM to ABCA1-expressing cells similarly reduced Cy2-apoA-I cell association. The representative apoA-I binding is shown in Fig. 6D. Because BAPTA-AM does not alter extracellular Ca2+ concentrations, diminished apoA-I cell association could not be simply due to disruptions in ligand-receptor binding on the cell surface. Buffering intracellular Ca2+ by BAPTA-AM must have perturbed intracellular processes required for apoA-I binding. Consistent with this notion, we found that both calcineurin inhibitors abolished apoA-I cell association (Fig. 6E, F). Importantly, we found that apoA-I cell association under the experimental conditions described here is positively correlated with the efficiency of cholesterol efflux to apoA-I (Fig. 6G), consistent with the interdependence between apoA-I association and cholesterol efflux observed among ABCA1 mutants (31). This relationship suggests that the Ca2+-dependent CaM/calcineurin signaling pathway is directly responsible for maintaining apoA-I interaction with ABCA1-expressing cells. Finally, specific inhibition of calcineurin signaling with CsA and FK506, respectively, did not alter ABCA1 expression or localization (data not shown). Furthermore, none of the treatments, i.e., EGTA, Ca2+, CsA, or FK506, affected cell viability, as evidenced by the MTT test (supplementary Fig. II). Also, consistent with previous observations by Takahashi et al. (11), removal of Ca2+ from the medium did not affect apoA-I binding at 4°C. In fact, 4°C apoA-I binding was intact under all treatment conditions (supplementary Fig. III).

Fig. 6.

Reducing intracellular and extracelluar Ca2+ caused an inhibition of Cy2-apoA-I cell association in BHK cells. Cy2-apoA-I was incubated with cells for 2 h under various conditions and the degree of cell association was determined by flow cytometry. The results are expressed relative to control cells that express ABCA1 (100%) and cells that do not express ABCA1 (mock) (0%). A: Mock- and ABCA1-expressing BHK cells incubated with Cy2-apoA-1. B: ABCA1-expressing cells were incubated with Cy2-apoA-1 plus unlabeled apoA-I. ABCA1-expressing cells were incubated with Cy2-apoA-1 in the presence of 2 mM EGTA (C); 50 μM BAPTA-AM (D); 10 μM CsA (E); 25 μM FK506 (F). The representative experiments are shown from at least three trials. G: The correlation between apoA-I cell association and efflux efficiency is presented.

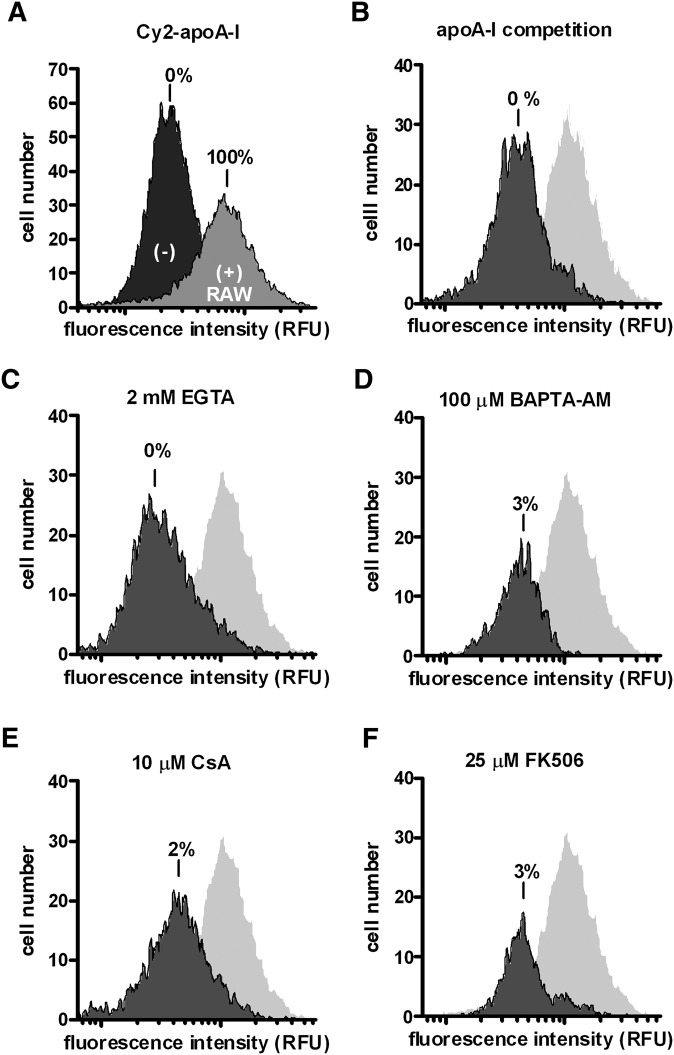

Similarly, we tested Cy2-apoA-I cell association in RAW macrophages. Control conditions indicated that Cy2-apoA-I interacts preferentially with ABCA1-expressing RAW cells (Fig. 7A), and effective competition occurred in the presence of unlabeled apoA-I (Fig. 7B). Removal of either intracellular or extracellular Ca2+ caused significant reductions in apoA-I association (Fig. 7C, D). Again, specific inhibition of calcineurin signaling with CsA and FK506 abolished apoA-I association in macrophages (Fig. 7E, F). We therefore conclude that the CaM/calcineurin signaling pathway is essential for both apoA-I cell-association and cholesterol efflux to apoA-I in ABCA1-expressing cells.

Fig. 7.

Manipulating Ca2+ and CaM/calcineurin signaling reduces Cy2-apoA-I cell association in RAW macrophages. Cells were incubated with Cy2-apoA-I for 2 h under various conditions and the degree of cell association was determined by flow cytometry. A: Cy2-apoA-I cell association in cells induced to express ABCA1 (+) (100%) and uninduced cells (−) (0%) is presented. B: ABCA1-expressing cells were incubated with Cy2-apoA-1 plus unlabeled apoA-I. ABCA1-expressing cells were incubated with Cy2-apoA-1 in the presence of 2 mM EGTA (C); 100 μM BAPTA-AM (D); 10 μM CsA (E); 25 μM FK506 (F). The representative experiments are shown from at least three trials.

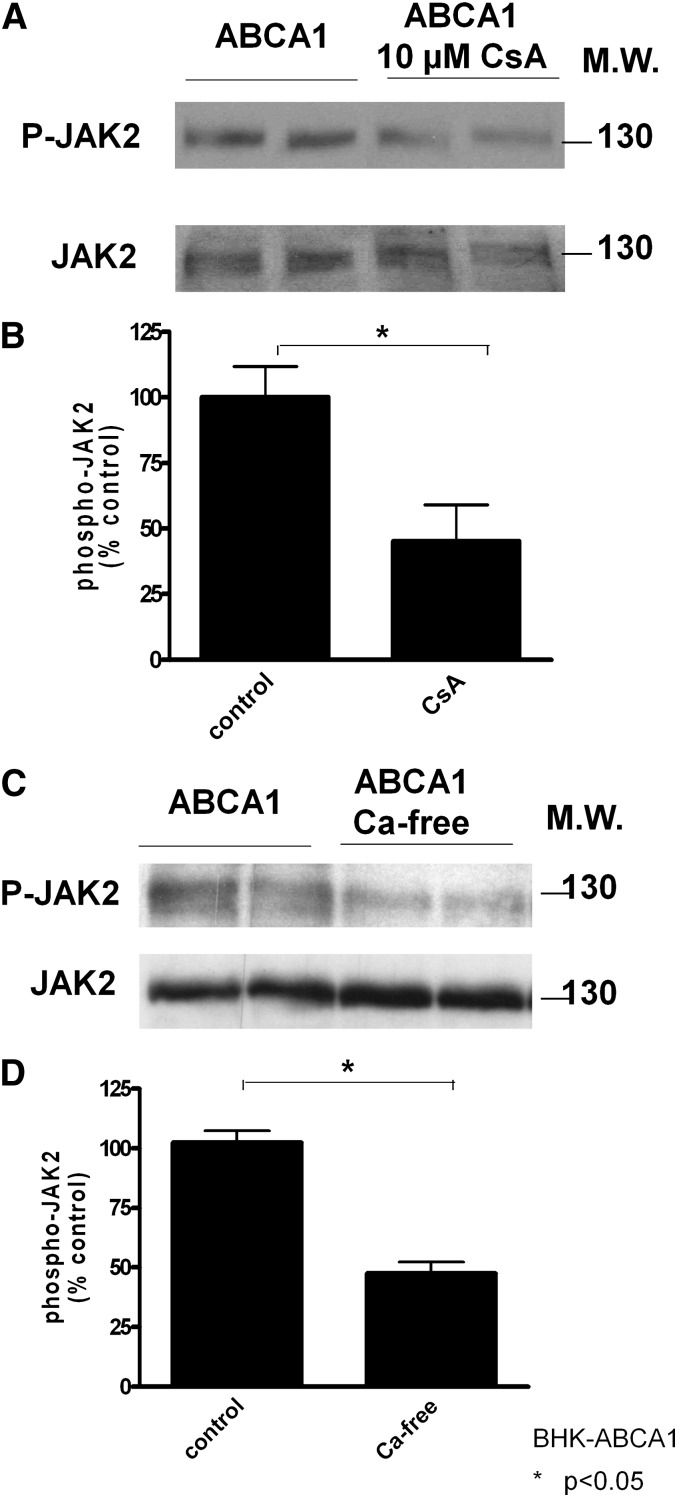

Interestingly, Oram et al. reported that JAK2 signaling is also necessary for apoA-I cell-association and cholesterol efflux to apoA-I (7). JAK2 becomes phosphorylated rapidly after ABCA1-expressing cells interact with apoA-I (7, 32), and JAK2 phosphorylation positively correlates with apoA-I cell association or cholesterol efflux to apoA-I (31). Also, cells lacking JAK2 were defective in cholesterol efflux to apoA-I (7). Therefore, we analyzed JAK2 phosphorylation in cells treated with calcineurin inhibitor CsA. CsA at 10 μM significantly inhibited JAK2 phosphorylation (Fig. 8A). Also, if the effect of CsA is to prevent calcineurin activation via Ca2+ influx, removal of extracellular Ca2+ should also jeopardize JAK2 activation. We indeed found similarly decreased JAK2 phosphorylation when extracellular Ca2+ was removed (Fig. 8B). Our results thus suggest that CaM/calcineurin likely operates upstream of JAK2 signaling and, together, they act to enhance apoA-I interactions with ABCA1-expressing cells and thus facilitate cholesterol efflux.

Fig. 8.

Inhibition of calcineurin impairs JAK2 phosphorylation. The expression levels of phosphorylated Jak2 (P-Jak2) and total Jak2 was determined by immunoblotting. A: Duplicates of ABCA1-BHK cells were induced with mifepristone overnight and then incubated with or without 10 μM CsA for 2 h before cell lysis and immunoblotting. B: ABCA1-expressing BHK cells were also incubated with Ca2+-free medium for 2 h before immunoblotting. The optical density of the immunoblots was quantified and expressed as mean ± SD. Untreated cells served as control (100%). Results are representative of three experiments with identical conditions.

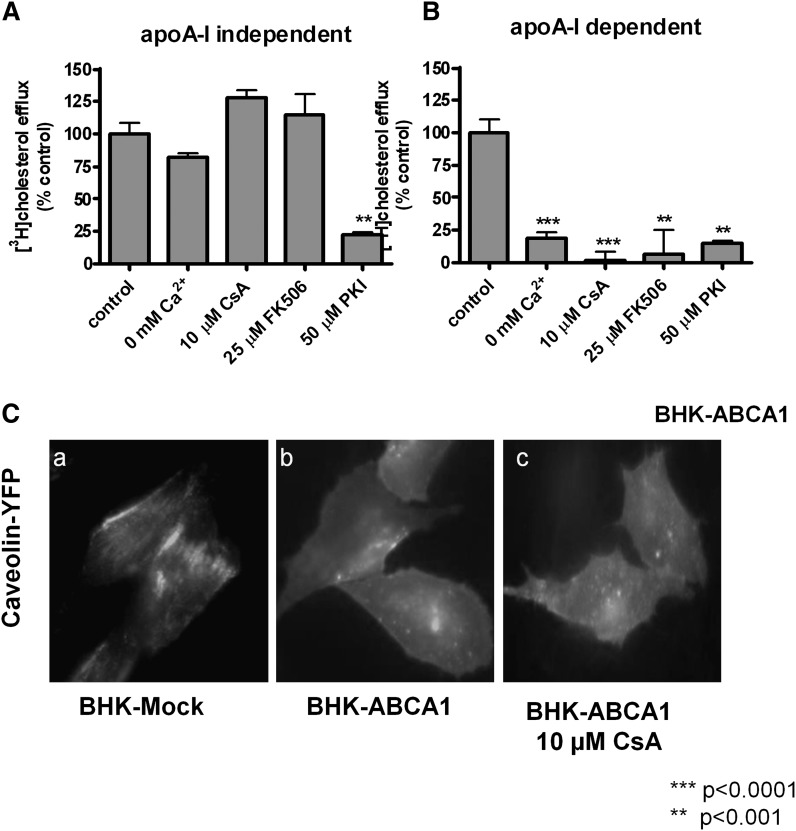

Finally, because disrupting the Ca2+-dependent CaM/calcineurin signaling pathway appeared to specifically perturb apoA-I binding to ABCA1-expressing cells but not ABCA1 protein expression or distribution, we wondered whether other ABCA1 functions also require Ca2+-dependent CaM/calcineurin signaling. We and others reported recently that ABCA1 expression leads to basal cholesterol efflux, independent of apoA-I, to produce microparticles (33, 34). Also, functional ABCA1 remodels the plasma membrane, also independent of apoA-I (36, 37). For the purpose of clarity, we collectively term these effects as “basal ABCA1 activity.” We treated cells with the various reagents described above and analyzed microparticle production and membrane remodeling. We found that apoA-I-independent efflux is completely insensitive to the perturbations of Ca2+-dependent CaM/calcineurin pathway (Fig. 9A), whereas the same perturbations abolished cholesterol efflux to apoA-I (Fig. 9B). Interestingly, the only shared pathway is PKA, because PKA inhibitor PKI inhibited both processes. It is also noteworthy that CsA seemed to increase apoA-I-independent efflux (Fig. 9A), which may reflect the trapping effect of CsA. CsA was reported to inhibit ABCA1 turnover on the plasma membrane, resulting in increased ABCA1 on the cell surface (27). The largely unperturbed basal activity in ABCA1-expressing cells also suggests that the manipulations used here did not cause general cytotoxicity. Cells indeed remained perfectly viable as judged by the MTT test (supplementary Fig. II).

Fig. 9.

Manipulating Ca2+ and calcineurin activity affects apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux, but not basal ABCA1 activity. ABCA1 BHK cells were labeled with [3H]cholesterol and induced with mifepristone overnight. Cholesterol efflux was conducted in the presence of apoA-I (A) or without (B) under the following conditions: Ca2+-free medium, calcineurin inhibitors (CsA and FK506), and PKI (a PKA inhibitor). Cholesterol efflux from untreated cells served as control (100%). Each panel presents data compiled from two experiments performed in triplicate and the standard error of the mean is shown. C: BHK cells were transfected with YFP-caveolin and induced with mifepristone overnight. Representative images of YFP-caveolin are shown in mock BHK cells, ABCA1-expressing BHK cells, and ABCA1-expressing BHK cells treated with 10 μM CsA.

We next tested ABCA1's capacity to remodel the plasma membrane. Functional ABCA1 causes caveolin to redistribute from largely clustered structures, presumably caveolae, to the general area of the plasma membrane (Fig. 9C, panels A and B), due mainly to generating more nonraft membrane microdomains (36). Disrupting Ca2+-dependent CaM/calcineurin signaling had little effect on this basal ABCA1 function; caveolin still diffusely decorated the plasma membrane in CsA-treated cells, undistinguishable from untreated ABCA1-expressing cells (Fig. 9C, panel C). These observations demonstrate that apoA-I specifically requires the CaM/calcineurin signaling pathway and, in the situation where calcineurin activity is inhibited, only apoA-I-related activities are diminished. ABCA1 still retained its capability to remodel the plasma membrane or generate microparticles. Together, we conclude that the CaM/calcineurin signaling pathway is a part of the cellular machinery that ABCA1 employs to specifically execute cholesterol efflux to apoA-I.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report that Ca2+ plays a critical role in ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. We provide evidence that either removal of extracellular Ca2+ or buffering intracellular Ca2+ severely impaired ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. apoA-I initiated Ca2+ influx from the extracellular medium in ABCA1-expressing cells, which potentially triggers intracellular signaling events. Indeed, we found that the Ca2+-activated CaM/calcineurin signaling pathway was required in cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. Both CsA and FK506, two structurally distinct and highly specific inhibitors of calcineurin, completely abolished cholesterol efflux to apoA-I and blocked apoA-I association with ABCA1-expressing cells. We also provide evidence that calcineurin signals through JAK2, an established signaling event required for cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. Interestingly, the CaM/calcineurin pathway influences only apoA-I lipidation and not the basal activity of ABCA1. Together, our results establish a novel signaling pathway that ABCA1 employs specifically to transfer cholesterol on to apoA-I.

Although the link between ion flux and ABCA1 activity has not been firmly established, many studies have used the chloride channel inhibitor, DIDS, as an ABCA1 antagonist. We found that either chloride channel inhibition with DIDS or chloride anion replacement with gluconate− and SCN− moderately inhibited cholesterol efflux (data not shown). This suggested that the chloride channel might only be indirectly involved and the modest inhibition may reflect disruptions to other plasma membrane ion channels. Indeed, we found Ca2+ channels played a much more pronounced role than chloride channels. This is supported by the following observations: a) apoA-I triggered Ca2+ influx, and b) manipulations that prevent this influx (removal of extracellular Ca2+) or dampen intracellular Ca2+ rise (BAPTA-AM) impaired cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. The dose response of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 1C, D) also indicates that a relatively low concentration of extracellular Ca2+ is sufficient to produce efficient cholesterol efflux. Consistent with this, a relatively high concentration of BAPTA-AM was needed to completely inhibit efflux (Fig. 1E). These observations collectively suggest that the Ca2+ flux that initiates the CaM/calcineurin pathway is of low aptitude, unlike what is often required with excitable cells or cells stimulated by hormones (23). It explains why we were only able to detect apoA-I-stimulated Ca2+ influx using 45Ca2+ (Fig. 3B). This is also consistent with the fact that calcineurin has the highest affinity for Ca2+-CaM (Kd = ∼0.1 nM), whereas many other targets, such as CaMKII (Kd = 50 nM), require much higher concentrations of Ca2+-CaM (26). It is tempting to suggest that low aptitude Ca2+ influx may serve to specifically activate the CaM/calcineurin pathway without significantly affecting other Ca2+-CaM activated processes, which may offer an explanation as to why a general CaM inhibitor, W-7, can only partially block cholesterol efflux to apoA-I (Fig. 4A).

The antagonists of the two ER Ca2+ channels, RyR and IP3R, and the SERCA pump had no effect on efflux (Fig. 3A). This was in contrast to our observations that BAY-K8644, which opens L-type Ca2+ channels, increased cholesterol efflux to apoA-I by 35% (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, the Ca2+ ionophore, A23187, did not further enhance cholesterol efflux (data not shown). Unlike influx through regulated channels, A23187 binds Ca2+ and shields it against the hydrophobicity of the lipid bilayer, causing unregulated entry of Ca2+ into cells. This lack of effect from A23187 may indicate that low aptitude Ca2+ influx induced by apoA-I alone is sufficient to activate calcineurin or, alternatively, only regulated influx of Ca2+ through specific plasma membrane channels can facilitate cholesterol efflux to apoA-I.

Extracellular Ca2+ is known to be necessary for cholesterol efflux to apoA-I (11). We now attribute this requirement to Ca2+ influx that activates the calcineurin pathway. In support of this view, intracellular Ca2+ buffering by BAPTA-AM was equally potent as removal of extracellular Ca2+. Interestingly, the effect of CsA in cholesterol efflux to apoA-I has also been documented previously (27), although the link to calcineurin was not defined. Because both CsA and FK-506, two unrelated and highly specific calcineurin inhibitors, completely blocked ABCA1-mediated cholesterol to apoA-I (Fig. 4), calcineurin activity is likely one of the essential components that enables apoA-I lipidation. This conclusion was further supported by the finding that blocking calcineurin activation by inhibitors or Ca2+ removal inhibited JAK2 phosphorylation (Fig. 8). JAK2 phosphorylation is a well-documented essential component for cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. Thus, our findings here place Ca2+ influx and calcineurin activation upstream of JAK2 phosphorylation.

It is intriguing to see that both Ca2+ manipulation and calcineurin inhibition abolish apoA-I cell association (Fig. 6) yet preserve 4°C apoA-I binding (supplementary Fig. III). This further supports our conclusion that Ca2+ and calcineurin function along the same pathway. It also suggests that initial binding of apo-A-I to ABCA1 is not sufficient to lipidate apoA-I and subsequent steps have to take place to produce effect cholesterol efflux.

Perhaps most interestingly, this Ca2+-activated calcineurin pathway is highly specific for ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. Interrupting this pathway has no influence on ABCA1 basal function, i.e., basal cholesterol efflux and plasma membrane remodeling (Fig. 9). Calcineurin, a phosphatase by nature, most likely exerts its function by regulating the phosphorylation status of other cellular proteins; this potentially includes ABCA1. However, because basal function of ABCA1 is totally insensitive to calcineurin activity, it is not likely that ABCA1 itself is a direct target of calcineurin. Consistent with this view, JAK2 does not directly phosphorylate ABCA1 or contribute to membrane remodeling (7). This is in sharp contrast with PKA. ABCA1 can be directly phosphorylated by PKA, and preventing PKA-dependent phosphorylation of ABCA1 by point mutations partially impairs phospholipid efflux to apoA-I (38). PKA is also essential for ABCA1 basal function (Fig. 9). We speculate that calcineurin regulates the phosphorylation of downstream target proteins, other than ABCA1, to support apoA-I lipidation. This also implies that apoA-I lipidation on the plasma membrane is not merely a biophysical event where apoA-I interacts with membrane bilayers. In addition to ABCA1, a cohort of proteins, made ready by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation by JAK2, calcineurin, and others, is required to participate in lipidating apoA-I. Disruption on this apoA-I activated cellular machinery could lead to premature release of apoA-I, thus diminished apoA-I cell-association, and failure of apoA-I lipidation.

In conclusion, we show for the first time that apoA-I induces Ca2+ influx from the extracellular medium. This rise in intracellular Ca2+ activates the CaM/calcineurin/JAK2 pathway to maintain apoA-I cell association, resulting in efficient cholesterol efflux to apoA-I.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- 2-APB

- 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate

- apoA-I

- apolipoprotein A-I

- CaM

- calmodulin

- CaMK

- calmodulin-dependent protein kinase

- cpm

- counts per minute

- CsA

- cyclosporine A

- DIDS

- disulphonic acid hydrate disodium salt

- FCS

- fetal calf serum

- InsP3R

- inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate-gated Ca2+ release channel

- Kd

- dissociation constant

- MTT

- methylthiazol tetrazolium

- RyR

- ryanodine receptor

- SERCA

- sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase

This work is supported by a grant-in-aid from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario (T6384). J. Karwatsky is supported by a Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada-AstraZeneca postdoctoral fellowship. L. Ma acknowledges an Ontario Scholarship in Science and Technology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Higgins C. F. 2001. ABC transporters: physiology, structure and mechanism–an overview. Res. Microbiol. 152: 205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nofer J. R., Remaley A. T. 2005. Tangier disease: still more questions than answers. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62: 2150–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haidar B., Denis M., Krimbou L., Marcil M., Genest J., Jr 2002. cAMP induces ABCA1 phosphorylation activity and promotes cholesterol efflux from fibroblasts. J. Lipid Res. 43: 2087–2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiss R. S., Maric J., Marcel Y. L. 2005. Lipid efflux in human and mouse macrophagic cells: evidence for differential regulation of phospholipid and cholesterol efflux. J. Lipid Res. 46: 1877–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nofer J. R., Feuerborn R., Levkau B., Sokoll A., Seedorf U., Assmann G. 2003. Involvement of Cdc42 signaling in apoA-I-induced cholesterol efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 53055–53062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roosbeek S., Peelman F., Verhee A., Labeur C., Caster H., Lensink M. F., Cirulli C., Grooten J., Cochet C., Vandekerckhove J., et al. 2004. Phosphorylation by protein kinase CK2 modulates the activity of the ATP binding cassette A1 transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 37779–37788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang C., Vaughan A. M., Oram J. F. 2004. Janus kinase 2 modulates the apolipoprotein interactions with ABCA1 required for removing cellular cholesterol. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 7622–7628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y., Oram J. F. 2007. Unsaturated fatty acids phosphorylate and destabilize ABCA1 through a protein kinase C delta pathway. J. Lipid Res. 48: 1062–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamauchi Y., Hayashi M., Abe-Dohmae S., Yokoyama S. 2003. Apolipoprotein A-I activates protein kinase C alpha signaling to phosphorylate and stabilize ATP binding cassette transporter A1 for the high density lipoprotein assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 47890–47897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez L. O., Agerholm-Larsen B., Wang N., Chen W., Tall A. R. 2003. Phosphorylation of a pest sequence in ABCA1 promotes calpain degradation and is reversed by ApoA-I. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 37368–37374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi Y., Smith J. D. 1999. Cholesterol efflux to apolipoprotein AI involves endocytosis and resecretion in a calcium-dependent pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96: 11358–11363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basu S. K., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. 1978. Characterization of the low density lipoprotein receptor in membranes prepared from human fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 253: 3852–3856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finn B. E., Forsen S. 1995. The evolving model of calmodulin structure, function and activation. Structure. 3: 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becq F., Hamon Y., Bajetto A., Gola M., Verrier B., Chimini G. 1997. ABC1, an ATP binding cassette transporter required for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells, generates a regulated anion flux after expression in Xenopus laevis oocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 2695–2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen L. H., Gromada J., Bouchelouche P., Whitmore T., Jelinek L., Kindsvogel W., Nishimura E. 1998. Glucagon-mediated Ca2+ signaling in BHK cells expressing cloned human glucagon receptors. Am. J. Physiol. 274: C1552–C1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofer A. M., Schlue W. R., Curci S., Machen T. E. 1995. Spatial distribution and quantitation of free luminal [Ca] within the InsP3-sensitive internal store of individual BHK-21 cells: ion dependence of InsP3-induced Ca release and reloading. FASEB J. 9: 788–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofer A. M., Curci S., Machen T. E., Schulz I. 1996. ATP regulates calcium leak from agonist-sensitive internal calcium stores. FASEB J. 10: 302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomez-Viquez L., Guerrero-Serna G., Garcia U., Guerrero-Hernandez A. 2003. SERCA pump optimizes Ca2+ release by a mechanism independent of store filling in smooth muscle cells. Biophys. J. 85: 370–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White C., McGeown J. G. 2003. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors modulate Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ store content in vas deferens myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 285: C195–C204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji G., Barsotti R. J., Feldman M. E., Kotlikoff M. I. 2002. Stretch-induced calcium release in smooth muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 119: 533–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borle A. B. 1990. An overview of techniques for the measurement of calcium distribution, calcium fluxes, and cytosolic free calcium in mammalian cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 84: 45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schramm M., Thomas G., Towart R., Franckowiak G. 1983. Novel dihydropyridines with positive inotropic action through activation of Ca2+ channels. Nature. 303: 535–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berridge M. J., Lipp P., Bootman M. D. 2000. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1: 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hidaka H., Inagaki M., Nishikawa M., Tanaka T. 1988. Selective inhibitors of calmodulin-dependent phosphodiesterase and other enzymes. Methods Enzymol. 159: 652–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song Q., Saucerman J. J., Bossuyt J., Bers D. M. 2008. Differential integration of Ca2+-calmodulin signal in intact ventricular myocytes at low and high affinity Ca2+-calmodulin targets. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 31531–31540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis B. A., Schwartz A., Samaha F. J., Kranias E. G. 1983. Regulation of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium transport by calcium-calmodulin-dependent phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 258: 13587–13591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Goff W., Peng D. Q., Settle M., Brubaker G., Morton R. E., Smith J. D. 2004. Cyclosporin A traps ABCA1 at the plasma membrane and inhibits ABCA1-mediated lipid efflux to apolipoprotein A-I. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24: 2155–2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorenzi I., von Eckardstein A., Cavelier C., Radosavljevic S., Rohrer L. 2008. Apolipoprotein A-I but not high-density lipoproteins are internalised by RAW macrophages: roles of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 and scavenger receptor BI. J. Mol. Med. 86: 171–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J., Farmer J. D., Jr., Lane W. S., Friedman J., Weissman I., Schreiber S. L. 1991. Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes. Cell. 66: 807–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ke H., Huai Q. 2003. Structures of calcineurin and its complexes with immunophilins-immunosuppressants. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 311: 1095–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaughan A. M., Tang C., Oram J. F. 2009. ABCA1 mutants reveal an interdependency between lipid export function, apoA-I binding activity, and Janus kinase 2 activation. J. Lipid Res. 50: 285–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang C., Vaughan A. M., Anantharamaiah G. M., Oram J. F. 2006. Janus kinase 2 modulates the lipid-removing but not protein-stabilizing interactions of amphipathic helices with ABCA1. J. Lipid Res. 47: 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duong P. T., Collins H. L., Nickel M., Lund-Katz S., Rothblat G. H., Phillips M. C. 2006. Characterization of nascent HDL particles and microparticles formed by ABCA1-mediated efflux of cellular lipids to apoA-I. J. Lipid Res. 47: 832–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nandi S., Ma L., Denis M., Karwatsky J., Li Z., Jiang X. C., Zha X. 2009. ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux generates microparticles in addition to HDL through processes governed by membrane rigidity. J. Lipid Res. 50: 456–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landry Y. D., Denis M., Nandi S., Bell S., Vaughan A. M., Zha X. 2006. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 expression disrupts raft membrane microdomains through its ATPase-related functions. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 36091–36101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaughan A. M., Oram J. F. 2003. ABCA1 redistributes membrane cholesterol independent of apolipoprotein interactions. J. Lipid Res. 44: 1373–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.See R. H., Caday-Malcolm R. A., Singaraja R. R., Zhou S., Silverston A., Huber M. T., Moran J., James E. R., Janoo R., Savill J. M., et al. 2002. Protein kinase A site-specific phosphorylation regulates ATP-binding cassette A1 (ABCA1)-mediated phospholipid efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 41835–41842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]