Abstract

The non-heme iron enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase from Chromobacterium violaceum has previously been shown to catalyze the hydroxylation of benzylic and aliphatic carbons in addition to the normal aromatic hydroxylation reaction. The intrinsic isotope effect for hydroxylation of 3-cyclochexylalanine by the enzyme was determined to gain insight into the reactivity of the iron center. With 3-[2H11-cyclohexyl]-alanine as substrate, the isotope effect on the kcat value was 1, consistent with an additional step in the overall reaction being significantly slower than hydroxylation. Consequently the isotope effect was determined as an intramolecular effect, measuring the amount of deuterium lost in the hydroxylation of 3-[1,2,3,4,5,6-2H6-cyclohexyl]-alanine. The ratio of 4-HO-cyclohexylalanine that retained deuterium to that which lost one deuterium atom was 2.8. This allowed calculation of 12.6 as the ratio of the primary deuterium kinetic isotope effect to the secondary isotope effect. This value is consistent with hydrogen atom abstraction by an electrophilic Fe(O) center and a contribution of quantum mechanical tunneling to the reaction.

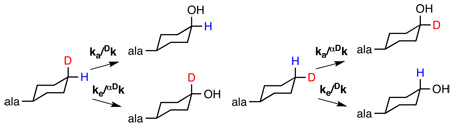

Phenylalanine hydroxylase (PheH) is a non-heme iron dependent monooxygenase that catalyzes the hydroxylation of the amino acid phenylalanine to yield tyrosine (Scheme 1)1. PheH is found in organisms ranging from bacteria to humans. In mammals, the enzyme is responsible for catabolism of dietary phenylalanine, and mutations in PheH are linked to the disorder phenylketonuria2. Among the bacterial enzymes, that from Chromobacterium violaceum (CvPheH) is the most studied3–6. PheH is a member of the family of aromatic amino acid hydroxylases, along with tyrosine hydroxylase (TyrH) and tryptophan hydroxylase1. Each of these enzymes catalyzes the hydroxylation of the corresponding aromatic amino acid using molecular oxygen and the electrons from a tetrahydropterin7. In addition to aromatic hydroxylation, the aromatic amino acid hydroxylases can catalyze the hydroxylation of benzylic and aliphatic substrates8–10. Previously, the isotope effect on benzylic hydroxylation was used to compare the reactivity of the eukaryotic enzymes and that of CvPheH6,10,11. These studies showed a similar reactivity for all the enzymes and suggested a common hydroxylating intermediate for all the family members.

Scheme 1.

Crystal structures of the three eukaryotic enzymes and CvPheH reveal a common fold for the catalytic domain12–14. The active sites are characterized by a ferrous iron coordinated on one face by two histidines and a glutamate. Three water molecules complete an octahedral geometry. When a tetrahydropterin and an amino acid substrate are present the geometry around the iron changes from six to five coordinate, presumably opening a site for oxygen to directly coordinate the iron15,16. The proposed hydroxylating intermediate is an Fe(IV)O species; direct evidence for such an intermediate has been obtained for TyrH17. Such a reactive intermediate could explain the rich chemistry displayed by these enzymes. Here we report the use of an intramolecular kinetic isotope effect as a probe of the chemical mechanism of aliphatic hydroxylation by CvPheH. The results shed light on the reactivity of the hydroxylating intermediate for the family of aromatic amino acid hydroxylases.

The hydroxylation of cyclohexylalanine by prokaryotic or eukaryotic PheH yields 4-HO-cyclohexylalanine as the only amino acid product, and amino acid hydroxylation is fully coupled to tetrahydropterin oxidation18. With 6-methyltetrahydropterin as the pterin substrate, we obtain kcat and kcat/Km values for cyclohexylalanine as substrate for CvPheH of 2.8 ± 0.1 s−1 and 45 ± 6 mM−1s−1, respectively, at 25 °C and pH 7, compared to values of 12 s−1 and 180 ± 20 mM−1 s−1 with phenylalanine as substrate6. In order to gain insight into the chemical mechanism of this reaction we measured deuterium kinetic isotope effects using 3-[2H11-cyclohexyl]-alanine18. The isotope effect on kcat was 0.99 ± 0.1 with 6,7-dimethyltetrahydropterin and 1.03 ± 0.1 with 6-methyltetrahydropterin. This result suggests that a step that does not involve hydrogen atom abstraction is rate-limiting with this substrate.

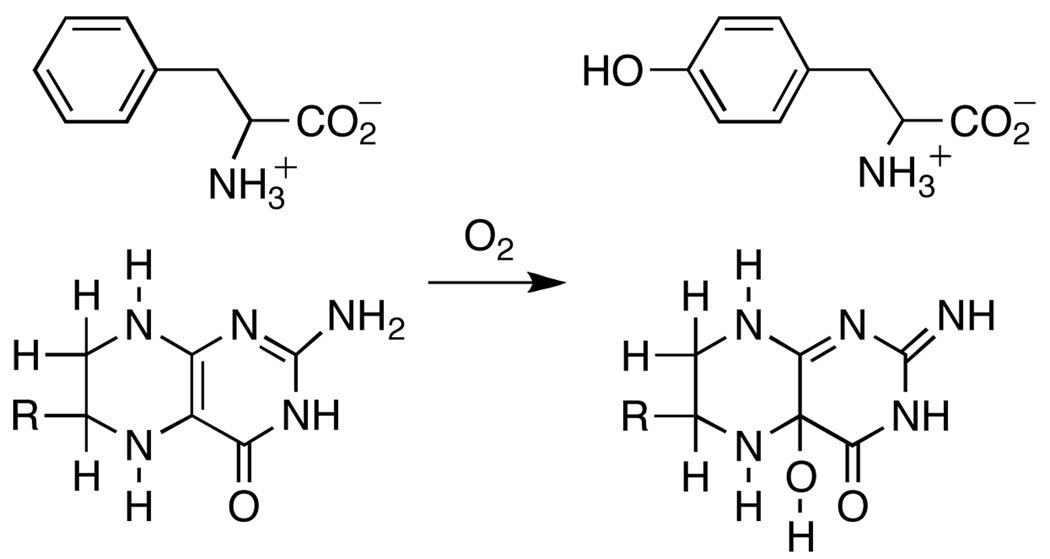

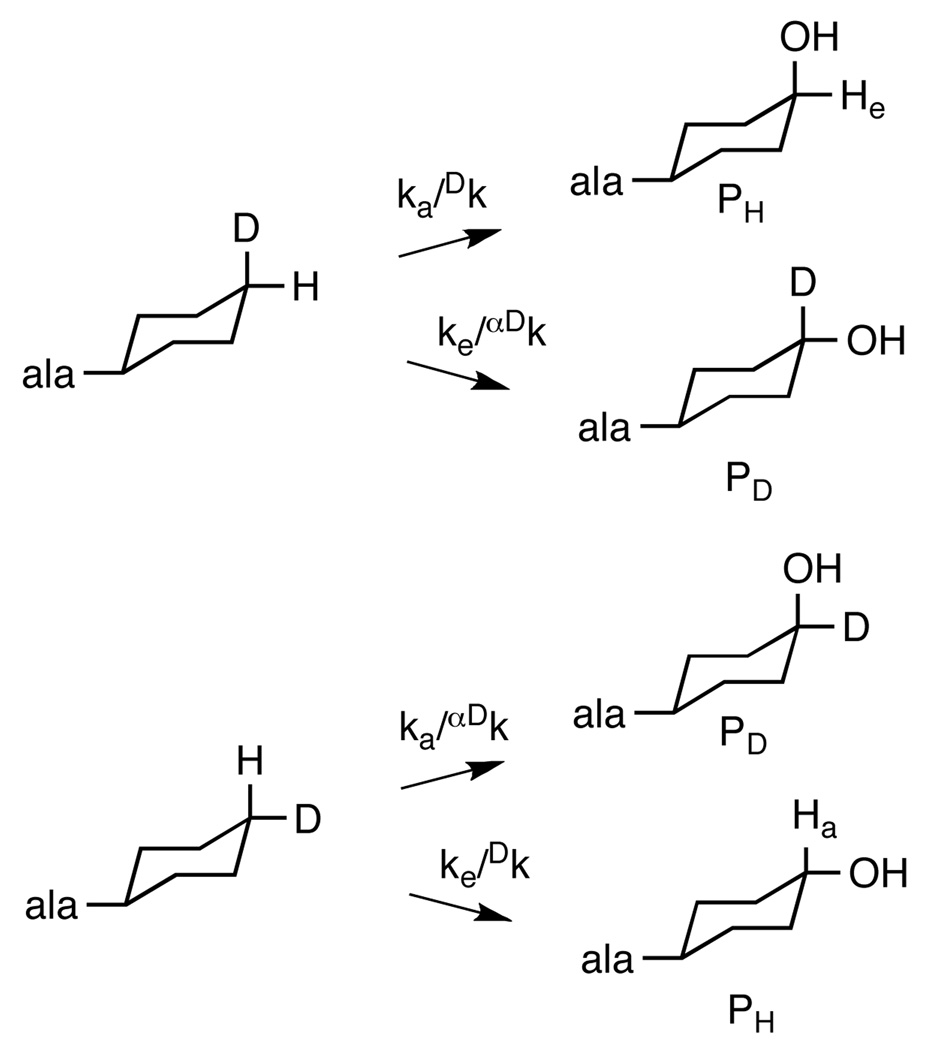

As an alternative approach, the isotope effect on the hydroxylation of cyclohexylalanine was analyzed as an intramolecular isotope effect. Such an approach can avoid the problem of slow, non-chemical steps19. To do so, 3-[1,2,3,4,5,6-2H6-cyclohexyl]-alanine18 was used as the substrate, so that the carbon of interest contained one deuterium and one hydrogen. The amount of deuterium in the 4-HO-cyclohexylalanine formed from 3-[1,2,3,4,5,6-2H6-cyclohexyl]-alanine was then determined by mass spectrometry of the isolated product11. If the 3-[1,2,3,4,5,6-2H6-cyclohexyl]-alanine was synthesized by reduction of phenylalanine with D2, the ratio of product with six deuteriums to that with five was 2.5 ± 0.1. When similar experiments were carried out with 3-[1,2,3,4,5,6-2H6-cyclohexyl]-alanine obtained by reduction of L-[ring-2H5]-phenylalanine with H2, the ratio of products was 3.03 ± 0.1.

The isotope effect for CH bond cleavage can be obtained from the partitioning between H and D abstraction if one makes two reasonable assumptions: 1) CH bond cleavage is irreversible, and 2) the cyclohexyl ring cannot flip in the active site more rapidly than CO bond formation occurs. The first assumption is reasonable for a hydroxylation reaction. The second is supported by the structure of human PheH with bound amino acid 15 and by the stoichiometric coupling of tetrahydropterin oxidation to amino acid hydroxylation with cyclohexylalanine as a substrate for CvPheH. The position of the hydroxyl group in the product is the result of the partitioning between hydroxylation of C4 at the axial position and hydroxylation at the equatorial position (Scheme 2). The ratio of the two products (Pa/Pe) is then described by eq 1. The monodeuterated substrate can be bound with deuterium in the axial or the equatorial position. If deuterium is in the axial position, the rate constant for cleavage of the axial CH bond, ka, will be subject to the primary kinetic isotope effect Dk and the rate constant for cleavage of the equatorial CH bond, ke, will be subject to the secondary isotope effect αDk. In this case the ratio of the product which has lost deuterium, PH, to that which retains deuterium, PD, is given by eq 2. If deuterium is in the equatorial position the isotope effects are on the opposite steps (Scheme 2), and the ratio of products is given by eq 3. No preference is anticipated for binding the substrate with deuterium in the equatorial versus the axial position. Thus, the isotopic content of the product will be the average of the contents from the two binding orientations (eq 4). Previously Carr et al.18 reported that 90% of the hydroxylation occurred at the axial position with cyclohexylalanine, so that ka/ke = 9. Combining this value with the average value of 0.36 ± 0.02 for PH/PD reported here yields a value for Dk /αDk of 12.6 ± 1.0. If an upper limit of 1.2 is used for the secondary isotope effect, Dk has an upper limit of 15.1 ± 1.2.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Scheme 2.

Intramolecular isotope effects on cyclohexylalanine hydroxylation.

The isotope effect on hydroxylation of cyclohexylalanine by CvPheH is slightly larger than that on benzylic hydroxylation by the enzyme of 10 ± 16. Given its magnitude, the intermolecular isotope effect of 12.6–15.1 is likely to be the intrinsic one. This value is comparable to the deuterium isotope effects on aliphatic hydroxylation by the α-ketoglutarate-dependent non-heme enzyme TauD (Dk = 16)20, which utilizes a Fe(IV)O center similar to that in PheH21, and by the heme-dependent cytochrome P450 (Dk =12)22,23. The magnitude of the value with CvPheH is consistent with a mechanism involving hydrogen atom abstraction by the Fe(IV)O center followed by rebound of the hydroxyl radical, a mechanism also suggested for the other enzymes. The large isotope effect also suggests the involvement of tunneling in this reaction24,25. Evidence of tunneling has also been demonstrated for the hydroxylation of benzylic carbons by all the aromatic amino acid hydroxylases6,10. The lack of an isotope effect on the kcat value with 3-[2H11-cyclohexyl]-alanine establishes that hydrogen atom abstraction is much faster than other steps in turnover, even though this enzyme is not evolved to carry out this reaction. Hydroxylation is similarly not the rate-limiting step in the hydroxylation of phenylalanine by CvPheH6. In the case of TyrH, product release has been shown to be substantially slower than hydroxylation of the normal substrate26.

The results presented here are consistent with the involvement of a highly reactive Fe(IV)O as the hydrogen atom abstracting species for the aliphatic hydroxylation carried out by CvPheH. The comparable magnitudes of the isotope effects on aliphatic hydroxylation by the aromatic amino acid hydroxylases and by α-ketoglutarate and heme-dependent enzymes and the ability of all three systems to catalyze aliphatic hydroxylation suggests that their hydroxylating intermediates have comparable reactivities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (GM47291) and The Welch Foundation (AQ-1245).

REFERENCES

- 1.Fitzpatrick PF. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:355–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisensmith RC, Woo SLC. Mol. Biol. Med. 1991;8:3–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onishi A, Liotta LJ, Benkovic SJ. J.Biol.Chem. 1991;266:18454–18459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carr RT, Benkovic SJ. Biochemistry. 1993;32:14132–14138. doi: 10.1021/bi00214a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen D, Frey PJ. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:25594–25601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panay AJ, Fitzpatrick PF. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11118–11124. doi: 10.1021/bi801295w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzpatrick PF. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14083–14091. doi: 10.1021/bi035656u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegmund H-U, Kaufman S. J.Biol.Chem. 1991;266:2903–2910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hillas PJ, Fitzpatrick PF. Biochemistry. 1996;35:6969–6975. doi: 10.1021/bi9606861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pavon JA, Fitzpatrick PF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:16414–16415. doi: 10.1021/ja0562651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frantom PA, Pongdee R, Sulikowski GA, Fitzpatrick PF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:4202–4203. doi: 10.1021/ja025602s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erlandsen H, Kim JY, Patch MG, Han A, Volner A, Abu-Omar MM, Stevens RC. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;320:645–661. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodwill KE, Sabatier C, Marks C, Raag R, Fitzpatrick PF, Stevens RC. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1997;4:578–585. doi: 10.1038/nsb0797-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Erlandsen H, Haavik J, Knappskog PM, Stevens RC. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12569–12574. doi: 10.1021/bi026561f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen OA, Stokka AJ, Flatmark T, Hough E. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;333:747–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chow MS, Eser BE, Wilson SA, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Fitzpatrick PF, Solomon EI. J. Amer. Chem Soc. 2009;131:7685–7698. doi: 10.1021/ja810080c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eser BE, Barr EW, Frantom PA, Saleh L, Bollinger JM, Jr, Krebs C, Fitzpatrick PF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11334–11335. doi: 10.1021/ja074446s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carr RT, Balasubramanian S, Hawkins PCD, Benkovic SJ. Biochemistry. 1995;34:7525–7532. doi: 10.1021/bi00022a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzpatrick PF. In: Isotope effects in Chemistry and Biology. Kohen A, Limbach H, editors. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 2005. pp. 861–873. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffart LM, Barr EW, Guyer RB, Bollinger JM, Jr, Krebs C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14738–14743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604005103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price JC, Barr EW, Tirupati B, Bollinger JM, Krebs C. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7497–7508. doi: 10.1021/bi030011f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groves JT, McClusky GA, White RE, Coon MJ. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1978;81:154–160. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91643-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones JP, Rettie AE, Trager WJ. Med. Chem. 1990;33:1242–1246. doi: 10.1021/jm00166a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pu J, Gao J, Truhlar DG. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3140–3169. doi: 10.1021/cr050308e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Limbach H-H, Lopez JM, Kohen A. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., Ser. B: Biol. Sci. 2006;361:1399–1415. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eser BE, Fitzpatrick PF. Biochemistry. 2010;49:645–652. doi: 10.1021/bi901874e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]