Abstract

The purpose of this research was to develop a sensitive and reproducible UPLC–MS/MS method to analyze matrine, an anticancer compound, and to use it to investigate its biopharmaceutical and pharmacokinetic behaviors in rats. A sensitive and fast UPLC–MS/MS method was successfully applied to determine matrine in rat plasma, intestinal perfusate, bile, microsomes, and cell incubation media. The absolute oral bioavailability of matrine is 17.1 ± 5.4% at a dose of 2 mg/kg matrine. Matrine at 10 μM was shown to have good permeability (42.5 × 10−6 cm/s) across the Caco-2 cell monolayer, and the ratio of PA–B to PB–A was approximately equal to 1 at two different concentrations (1 and 10 μM). Perfusion study showed that matrine displayed significant differences (P < 0.05) in permeability at different intestinal regions. The rank order of permeability was ileum (highest, Pw = 6.18), followed by colon (Pw = 2.07), duodenum (Pw = 0.61) and jejunum (Pw = 0.52). Rat liver microsome studies showed that CYP and UGTs were not involved in matrine metabolism. In conclusion, a sensitive and reliable method capable of measuring matrine in a variety of matrixes was developed and successfully used to determine absolute oral bioavailability of matrine in rats, transport across Caco-2 cell monolayers, absorption in rat intestine, and metabolism in rat liver microsomes.

Keywords: Matrine, Caco-2 cells, Rat intestine perfusion, Pharmacokinetics, Microsomes, UPLC–MS/MS

1. Introduction

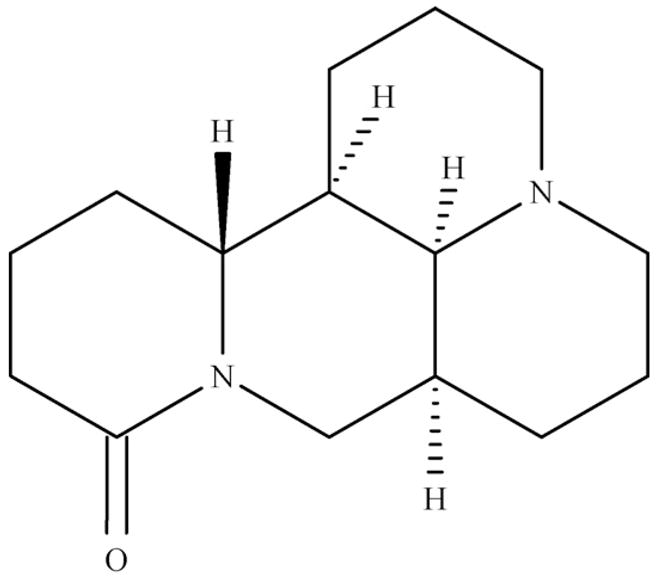

Matrine (Fig. 1), an alkaloid purified from the Chinese herb Sophora flavescens Ait (Chinese Pharmacopoeia 2005), is used as a quality control marker in anti-tumor B mixture. Anti-tumor B (ATB) is a Chinese traditional medicine, and contains a proprietary mixture of six plants including Sophora tonkinensis, Polygonum bistorta, Prunella vulgaris, Sonchus brachyotus, Dictamnus dascycarpus, and Dioscorea bulbifera. Previous clinical studies have shown significant chemopreventive efficacy of ATB against human esophageal and lung cancers. A clinical human trial of ATB is under investigation in BC Cancer Agency (Vancouver, BC, Canada) [1,2]. Matrine itself also has a wide spectrum of pharmacological actions including hepatoprotective activity on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice [3], proapoptotic activity in gastric carcinoma cells [4], and leukemia cells [5].

Fig. 1.

The structure of matrine.

In order to enhance the development potentials of matrine as a chemopreventative agent, there is a need to further understand the in vitro and in vivo absorption and clearance characteristics of matrine. There are several papers on matrine pharmacokinetics studies using oral administration of matrine alone and as a part of an herbal mixture [6–8]. But information on matrine’s absolute oral bioavailability and its intestinal absorption mechanism were not found in the published literatures. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to (1) develop a sensitive and reliable UPLC–MS/MS method to determine matrine concentration in different matrixes; (2) study matrine pharmacokinetic behavior in rats; and (3) investigates the utility of the present method in defining matrine’s biopharmaceutical characteristics (e.g., absorption/metabolism).

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Cloned Caco-2 cells (TC7) cells were a kind gift from Dr. Monique Rousset of INSERM U178 (Villejuit, France). Matrine, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP), glucose-6-phosphate sodium (6-DP), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (6-DPD), saccharolactone, alamethicin, magnesium chloride, phosphoric acid, Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS; powder form), sodium citrate, potassium phosphate dibasic, testosterone, rutin, 6β-hydroxytestosterone were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Genistein was purchased from LC laboratories (Woburn, MA). Genistein 7-O-glucuronide was extracted and separated from rat intestine perfusate sample, and was confirmed by mass spectrometer. Oral suspension vehicle was obtained from Professional Compounding Centers of America (Houston, TX). All other materials (typically analytical grade or better) were used as received.

2.2. Instruments and conditions

An API 3200 Qtrap triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystem/MDS SCIEX, Foster City, CA, USA) was used to determine matrine’s concentration in aqueous and plasma medium by MRM (Multiple Reaction Monitoring) method in the positive ion mode. The main working parameters for mass spectrum were set as follows: ionspray voltage, 5.5 kV; ion source temperature, 400 °C; gas1, 30 psi; gas2, 40 psi; curtain gas, 10 psi.

Testosterone was used as an internal standard to analysis matrine in plasma, cell culture medium, intestinal perfusate and bile samples. Conversion of genistein to genistein-7-O-glucuronide by UGT, and conversion of testosterone to 6-hydroxytestosterone by CYP were measured and used as positive controls in matrine’s metabolism study. Genistein and genistein 7-O-glucuronide were determined by MRM method in negative mode. Because rutin can be determined both in positive and negative mode, it was used as an internal standard in matrine’s metabolism study as testosterone was used as the substrate for phase I metabolism via Cytochrome P4503A (or CYP3A). The quantification was performed using MRM method with the transitions of m/z 249 → m/z 148 for matrine, m/z 289 → m/z 97 for testosterone (IS), m/z 611 → m/z 303 (positive mode) and m/z 609 → m/z 300 (negative mode) for rutin (IS), m/z 269 → m/z 133 for genistein, m/z 445 → m/z 269 for genistein 7-O-glucoronide and m/z 305 → m/z 269 for 6-hydroxytestosterone. The Compound dependent parameters in MRM mode for matrine and other compounds are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Compound dependent parameters for matrine and other compounds in MRM mode for UPLC–MS/MS analysis.

| Analyte | Q1 mass (U) | Q3 mass (U) | Dwell time (ms) | DP (V) | CEP (V) | CE (V) | CXP (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matrine | 249 | 148 | 100 | 96 | 23 | 49 | 2 |

| Testosterone | 289 | 97 | 100 | 60 | 20 | 33 | 2 |

| Rutin | 611 | 303 | 100 | 30 | 37 | 28 | 4 |

| 6β-hydroxytestosterone | 305 | 269 | 100 | 39 | 26 | 18 | 4 |

| Genistein | 269 | 133 | 100 | −80 | −22 | −40 | −3 |

| Genistein 7-O-glucuronide | 445 | 269 | 100 | −30 | −34 | −40 | −3 |

| Rutin | 609 | 300 | 100 | −50 | −31 | −49 | −2 |

UPLC conditions for analyzing matrine in plasma, HBSS, intestine perfusate, and bile samples were: system, Waters Acquity™ with diode array detector (DAD); column, Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (50 × 2.1 mm I.D., 1.7 μm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA); mobile phase A, 0.1% formic acid; mobile phase B, 100% acetonitrile; gradient, 0–0.4 min, 0–1% B, 0.4–0.8 min, 1–5% B, 0.8–1.6 min, 5–40% B, 1.6–2 min, 40–90% B, 2–2.4 min, 90–95% B, 2.4–3 min, 95% B, 3–3.7 min, 95–0%, 3.7–3.8 min, 0% B; flow rate, 0.45 ml/min; column temperature, 45 °C; and injection volume, 10 μl.

UPLC conditions for analyzing matrine in microsome samples were: mobile phase A, 0.1% formic acid; mobile phase B, 100% acetonitrile; gradient, 0–0.4 min, 0–1% B, 0.4–0.8 min, 1–5% B, 0.8–1.6 min, 5–40% B, 1.6–2 min, 40–90% B, 2–2.4 min, 90–95% B, 2.4–2.8 min, 95% B, 2.8–3.4 min, 95–0% B. All the other conditions were the same as the above one.

Mass spectrometer and UPLC conditions for analyzing testosterone, 6β-hydroxytestosterone and genistein, genistein 7-O-glucuronide in microsome samples were slightly different from the above method (details not shown since the paper is focused on matrine).

2.3. Pharmacokinetic study in vivo

2.3.1. Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (250–300 g, 8–10 weeks old) were from Harlan Laboratory (Indianapolis, IN) and kept in an environmentally controlled room (temperature: 25 ± 2 °C, humidity: 50 ± 5%, 12 h dark–light cycle) for at least 1 week before the experiments. The rats were fasted overnight before the day of the experiment.

2.3.2. Experimental design

The animal protocols used in this study were approved by the University of Houston’s Institutional Animal Care and Uses Committee. Rats were fasted for 12 h with free access to water prior to the pharmacokinetic study. Two groups of rats were treated as following: i.v. injection of matrine in saline was administrated through lateral tail vein at dose of 2 mg/kg. An oral gavage of matrine dispersed in oral suspension vehicle was given to rats at the same dose. After a rat was anesthetized with isoflurane gas, its tail was snipped near the tip of the tail to allow the collection of blood samples. Blood samples (100–150 μl) were collected in heparinized tubes at 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, 120, 240, 360, 480, 600 and 1440 min, respectively, after an i.v. administration, or 15, 30, 45, 60, 120, 180, 240, 360, 480, 600 and 1440 min, respectively after an oral administration. The blood samples were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min and the plasma samples obtained were stored at −20 °C until analysis.

2.3.3. Plasma sample preparation

The plasma (50 μl) was spiked with 10 μl of I.S. (testosterone, 10 μg/ml). The mixture was then extracted with 200 μl acetonitrile by vortex for 1 min. After centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 15 min, the supernatant were transferred to a new tube and evaporated to dryness under a stream of nitrogen. The residue was reconstituted in 200 μl of 30% acetonitrile aqueous solution and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 min. 10 μl of supernatant was injected into the UPLC–MS/MS system for quantitative analysis.

2.3.4. Preparation of standard and quality control samples

Stock solution of matrine was prepared in acetonitrile at a concentration of 2 mg/ml. The stock solution of testosterone (I.S.) was prepared in acetonitrile at a concentration of 100 μg/ml. Calibration standard samples for matrine were prepared in blank rat plasma at concentrations of 1.22, 2.44, 9.75, 39, 78, 156, 625, 1250, 2500 ng/ml. The quality control (QC) samples were prepared at low (2.44 ng/ml), medium (78 ng/ml), and high (1250 ng/ml) concentrations in the same way as the plasma samples for calibration, and QC samples were stored at −20 °C until analysis.

2.3.5. Method validation

2.3.5.1. Calibration curve and LLOQ

Calibration curves were prepared according to Section 2.3.3. The linearity of each calibration curve was determined by plotting the peak area ratio of matrine to I.S. in rat plasma. 1/χ2 least-squares linear regression method was used to determine the slope, intercept and correlation coefficient of linear regression equation. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was determined based on the signal-to noise ratio of 10:1.

2.3.5.2. Precision and accuracy

The “Intra-day” and “Inter-day” precision and accuracy of the method were determined with three different concentrations QC samples on the same day or on three different days.

2.3.5.3. Extraction recovery and matrix effect

The extraction recovery of matrine was determined by comparing (a) the peak areas obtained from blank plasma spiked with analytes before the extraction with (b) those from samples to which analytes were added after the extraction. Matrix effect was assayed to compare (a) the peak areas of blank plasma extracts spikes with analytes with (b) those of the standard solutions dried and reconstituted with mobile phase.

2.3.5.4. Stability

Short-term (25 °C for 4 h), long-term (−20 °C for 14 days) and three freeze-thaw cycle stabilities were determined.

2.3.6. Data analysis

WinNonlin 3.3 was used for pharmacokinetic analysis of the matrine concentrations. The noncompartmental approach was applied for analysis of the data following i.v. and oral administration of matrine.

2.4. Caco-2 cell model

2.4.1. Cell culture

Caco-2 transport study has been routinely done by our lab for almost two decades. The culture conditions for growing Caco-2 cells had been described previously [9,10]. To seed the cells, we used 3 μm porous polycarbonate cell culture inserts from Nunc (distributed by VWR International), which has a surface area of 4.2 cm2. The seeding density (60,000 cells/cm2), growth media (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum), and quality control criteria were all implemented according to previous published reports [9,10]. Caco-2 TC7 cells were fed every other day, and cell monolayers were ready for experiments from 19 to 22 days postseeding.

2.4.2. Transport experiments in the Caco-2 cell culture model

Experiments in triplicate were performed in HBSS [9,10]. The protocol for performing cell culture experiments was the same as described previously [10]. Briefly, the cell monolayers were washed three times with HBSS at 37 °C. The transepithelial electrical resistance values were measured and those with transepithelial electrical resistance values less than 420 Ω/cm2 difference compared with the blank were discarded. The monolayers were incubated with the HBSS buffer for 1 h, and the incubation medium was then aspirated. Afterwards, 2.5 ml of matrine solution (of appropriate concentration) in HBSS was loaded onto the apical side and 2.5 ml blank HBSS solution onto the basolateral side. Five sequential samples (0.5 ml) were taken at different times (0, 30, 60, 90, 120 min) from the apical and basolateral sides. The same volume of donor solution (matrine solution) and receiver medium (HBSS solution) was replaced after each sampling. 50 μl of internal standard solution (10 μM testosterone in 100% acetonitrile) was immediately added to 200 μl of samples to stabilize them until analysis. The mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was analyzed by UPLC–MS/MS.

2.4.3. Data analysis in the Caco-2 cell culture model

The apparent unidirectional permeability was obtained according to the following equation (Eq. (1)):

| (1) |

where Bt is the apparent appearance rate of drug molecules in the receiver side, S is the surface area of the monolayer (4.2 cm2), and C is the starting concentration in the donor side. Rate of transport (Bt) was obtained using rate of change in concentration of transported matrine as a function of time and volume of the sampling chamber (V) (Eq. (2)).

| (2) |

2.5. In situ four segments rat intestinal perfusion model

2.5.1. Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats of similar age and weight as those used in the pharmacokinetics studies were obtained from Harlan Laboratory.

2.5.2. Animals surgery

The perfusion protocol was approved by University of Houston’s Institutional Animal Care and Uses Committee. The intestinal surgical procedures were described in many of our previous publications [11–13]. Four segments of intestine, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon (8–12 cm for each of them) were simultaneously cannulated and a bile duct cannulation was added with no disruption of circulation to the liver and intestine. The perfusion was performed by an infusion pump (Model PHD 2000; Harvard Apparatus, Cambridge, MA) at a flow rate of 0.191 ml/min with 10 μM matrine in pH 7.4 HBSS iso-osmotic solution. To keep the temperature of the perfusate constant, the inlet cannulate was insulated and kept warm by a 37 °C circulating water bath.

2.5.3. Transport experiments in perfused rat intestinal model

A single-pass perfusions method described previously was used to perfuse four segments of the intestine (duodenum, upper jejunum, terminal ileum, and colon) [11]. A flow rate of 0.191 ml/min was used, and after a 30 min washout period with perfusate, four-site perfusates and bile samples were collected every 30 min (30, 60, 90, 120, 150 min). After perfusion, the length of the each segment of intestine was measured and each tube containing sample was weighted as described previously [11]. The perfusate samples were immediately processed at the same way as the Caco-2 samples were analyzed, and bile samples were diluted (1:20) with HBSS solution before determination. The outlet concentration of matrine was determined by UPLC–MS/MS.

2.5.4. Data analysis in the rat intestinal perfusion model

In the intestinal model, the wall permeability (Pw) was calculated at steady state using the following equations:

| (3) |

where

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

In Eqs. (4)–(6), Cm and C0 are outlet and inlet concentrations, respectively; while Gz, or Graz number, is the same as previously defined [14].

The Pw values are a much better representation of the intestinal membrane permeability and compounds with a Pw larger than one are generally well absorbed (≥75%) [15].

2.6. Metabolism of matrine in phase I and II reaction systems

To determine whether matrine is extensively metabolized via CYP or UGT enzymes, rat liver microsome studies were used.

2.6.1. Rat liver microsomes preparation

Male Rat liver microsomes were prepared as described previously [16]. The resulting microsomes were suspended in 250 mM sucrose, separated into microcentrifuge tubes (0.2 ml), and stored at −80 °C until use.

2.6.2. CYP reaction system

The incubation procedures for CYP reaction using liver microsomes were the same as those published previous by our laboratory [17,18]. The conditions were as follows: (1) mix microsomes (final concentration ≈ 0.36 mg protein/ml), NADP (2.61 mM), 6-DP (6.6 mM), MgCl2 (6.6 mM), 10 μM matrine in a 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and 6-DPD in 5 mM sodium citrate solution (40 U/ml, add last); (2) incubate the mixture (final volume = 200 μl) at 37 °C for 1 h; (3) end the reaction with the addition of 50 μl rutin (as the internal standard) solution in acetonitrile. The samples were vortexed for 30 s, centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min, and 10 μl of supernatant was injected into UPLC–MS/MS system for analysis (see Section 2.2). EMS (enhanced mass spectrometer) mode was used to search for possible CYP metabolites of matrine. Positive control experiment was done by determining the concentrations of 6β-hydroxytestosterone and testosterone after 10 μM testosterone was incubated in the same conditions.

2.6.3. UGT reaction system

The incubation procedures for UGT (UDP-glucuronosyltransferases) reaction using liver microsomes were the same as those published previous by our laboratory [16,19]. The conditions were as follows: (1) mix microsomes (final concentration ≈ 0.36 mg protein/ml), magnesium chloride (0.88 mM), saccharolactone (4.4 mM), alamethicin (0.022 mg/ml), 10 μM matrine in a 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and UDPGA (3.5 mM, add last); (2) incubate the mixture (final volume = 200 μl) at 37 °C for 1 h; (3) end the reaction with the addition of 50 μl rutin (as the internal standard) solution in acetonitrile. The samples were vortexed for 30 s, centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min, and 10 μl of supernatant was injected into UPLC–MS/MS system for analysis (see Section 2.2). EMS mode was used to search for possible UGT metabolites of matrine. Positive control experiment was done by determining the concentrations of genistein and genistein 7-O-glucuronide after 10 μM genistein was incubated under the same conditions.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The data in this paper were presented as means ± RSD, if not specified otherwise. Significance differences were assessed by using unpaired Student’s t-test. A P value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Chromatography and mass spectrometry

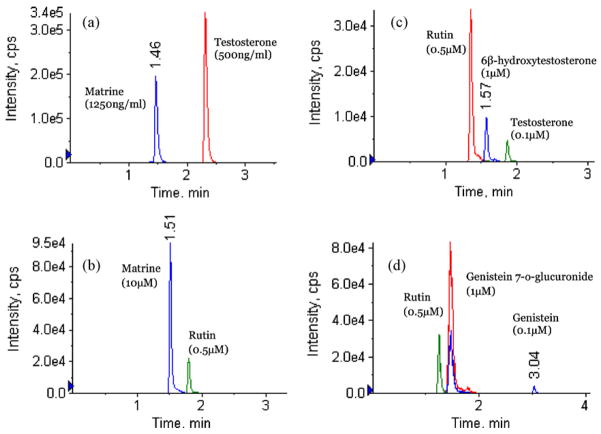

A specific, reliable and sensitive method to determine matrine concentration had been established. The LLOQ of this UPLC–MS/MS method was 0.305 ng/ml, which was more than 10 times lower than the published method by Zhang et al. [6,20]. In that paper, isopropanol: ethyl acetate (5: 95) was used to extract human plasma sample and LLOQ was determined to be 5 ng/ml [8]. In this study, acetonitrile was used to precipitate rat plasma protein directly, which improved recovery. The matrix effect observed in Zhang et al.’s paper when using acetonitrile to extract samples was not observed in this study. This difference may be due to the use of UPLC in our method or different plasma or both. This newly established method enabled us to determine the concentration of matrine in vivo after administration of a low dose of matrine, which is moderately toxic. Typical chromatograms of spiked matrine in rat plasma sample and blank microsome samples are shown in Fig. 2a and b, respectively. Typical chromatograms of spiked testosterone, 6β-hydroxytestosterone and genistein, genistein 7-O-glucuronide in blank microsome samples are shown in Fig. 2c and d, respectively. There were no significant interference substances observed at the retention time of matrine in plasma or microsome samples. This method also afforded us to determine matrine concentration in Caco-2 cell medium, rat intestine perfusate and bile samples.

Fig. 2.

Sample chromatograms of different analytes in current UPLC system with MS/MS detection. (a) A blank plasma sample spiked with matrine (2500 ng/ml) and testosterone (500 ng/ml). (b) A blank microsome sample spiked with matrine (10 μM) and rutin (0.5 μM). (c) A blank microsome sample spiked with rutin (0.5 μM), 6β-hydroxytestosterone (1 μM) and testosterone (0.1 μM). (d) A blank microsome sample spiked with rutin (0.5 μM), genistein 7-O-glucuronide (1 μM) and genistein (0.1 μM).

3.2. Linearity, precision and accuracy, recovery, matrix effect, stability

Considering that plasma is the most complex matrix among all the samples (Caco-2 medium, intestine perfusate and bile) collected from various studies, the method validation was conducted in rat plasma. The standard curves for matrine in plasma was linear in the concentration range of 0.61–2500 ng/ml with correlation coefficient values >0.997 (the weight is 1/χ2). The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was 0.305 ng/ml, defined as a signal-to-noise ratio of ≥10. The standard curve for matrine in other matrix were all linear in the concentration range of 0.61–2500 ng/ml with correlation coefficient values >0.99 (the weight is 1/χ2).

Intra-day and Inter-day precision and accuracy were determined by measuring six replicates of QC samples at three concentration levels in rat plasma. The precision and accuracy are shown in Table 2. These results demonstrated that the precision and accuracy values were well within the 15% acceptance range.

Table 2.

Intra-day and Inter-day precision and accuracy for matrine in MRM mode of UPLC–MS/MS analysis.

| Analyte | Concentration (ng/ml) | Intra-day (n = 6) |

Inter-day (n = 6) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (bias, %) | Precision (CV, %) | Accuracy (bias, %) | Precision (CV, %) | ||

| 2.44 | 91.14 | 3.89 | 89.76 | 7.13 | |

| Matrine | 78.0 | 106.44 | 4.62 | 103.08 | 3.31 |

| 1250 | 101.98 | 4.83 | 104.66 | 7.11 | |

The mean extraction recoveries determined using three replicates of QC samples at three concentration levels in rat plasma were found 74.2 ± 5.9%, 74.8 ± 2.1%, and 77.2 ± 2.4% for 2.44, 78 and 1250 ng/ml, respectively.

As for ionization, the peak areas of matrine after spiking evaporated plasma samples at three concentration levels were comparable to similarly prepared aqueous standard solutions (ranged from 93.8% to 109.2%), suggesting that there was no measurable matrix effect that interfered with matrine determination in rat plasma. Rat intestine perfusate and Caco-2 medium had no significant matrix effect after comparing the standard curve of these two matrixes with their respective aqueous samples. Bile sample was diluted 20 times with mobile phase before analysis, and matrix effect appeared to be minimal.

The stability of matrine in plasma and HBSS medium were evaluated by analyzing three replicates of quality control samples containing 2.44, 78 and 1250 ng/ml matrine after short-term storage (25 °C, 4 h), long-term cold storage (−20 °C, 14 days) and within three freeze-thaw cycles. All the samples displayed 90–110% recoveries after various stability tests, which were similar to those reports previously [6,20].

Taken together, the above results showed that a sensitive, reproducible, and robust method for the analysis of matrine in multiple sample matrixes has been developed, and validated for us in the analysis of matrine in blood, bile, and Caco-2 transport media.

3.3. Pharmacokinetic studies

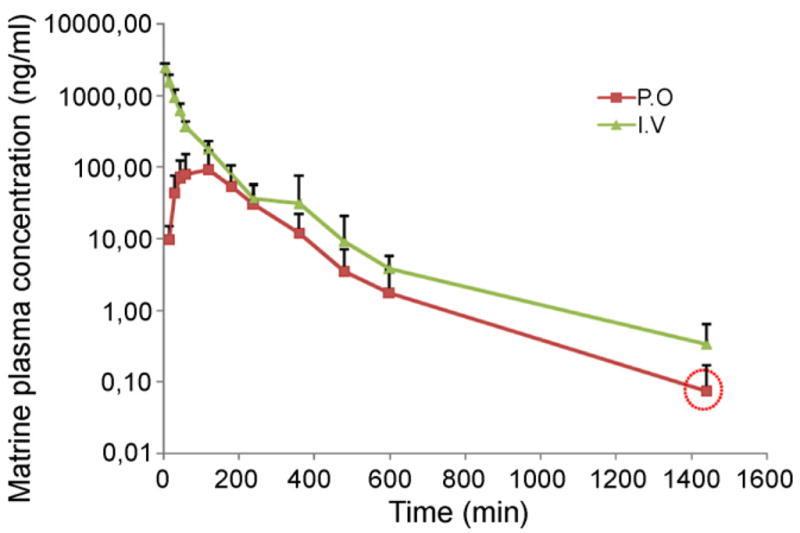

The validated analytical method was first employed to study the pharmacokinetic behaviors of matrine in rat. The mean plasma concentration-time curves of matrine after i.v. and p.o. administration are presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Plasma concentration–time curves of matrine after i.v. and p.o. administration of matrine (2 mg/kg). Each point represents an average of four determinations and the error bars are standard deviations of the mean. The point in the circle represents the average concentration, which is an approximate value since not all samples contained quantifiable matrine.

Matrine pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated by the noncompartmental method, using WinNonlin 3.3 (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, California). The fitted pharmacokinetic parameters are shown in Table 3. The oral bioavailability was calculated by using AUCoral/dose divided by AUCiv/dose.

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of matrine in rat plasma (n = 4) after i.v. and oral administration of matrine.

| Parameter | i.v. | p.o. |

|---|---|---|

| Cmax (ng/ml) | – | 94.6 ± 38.6 |

| Tmax (min) | – | 105 ± 30 |

| AUC0–t (min ng/ml) | 108,637 ± 11,801 | 18,453 ± 5885 |

| AUC0–∞ (min ng/ml) | 108,794 ± 11,712 | 18,593 ± 5931 |

| t½ (min) | 142 ± 79 | 92 ± 32 |

| Ke (1/min) | 0.0060 ± 0.0030 | 0.0081 ± 0.0023 |

| V (ml/kg) | 3704 ± 1874 | 2433 ± 1668 |

| CL (ml/min/kg) | 18.6 ± 2.0 | 19.7 ± 5.5 |

| Bioavailability (%) | – | 17.1 ± 5.4 |

After 2 mg/kg intravenous bolus injection, matrine concentration reached a maximum of 2412 ± 362 ng/ml and then declined rapidly. After oral administration of the same dose, matrine was readily absorbed and reached Cmax 92.4 ± 77.7 ng/ml at approximately 105 min (Fig. 3). These Cmax and Tmax values (following oral adminstration) were not significantly different from those reported by Wu et al. and Zhang et al. after we accounted for the differences in dose [6,7]. Wu et al. performed a pharmacokinetic study of pure matrine in rat after oral dose of 40 mg/kg, the Cmax was approximately 3900 ng/ml and Tmax was approximately 50 min [7]. Zhang, et al. published a pharmacokinetic study of matrine in rats after oral administration of Sophora flavescens Ait extraction (0.56 g/kg). The Cmax was 2529 ng/ml and Tmax was 2.08 h [6].

The absolute bioavailability of matrine by oral route was only 17.1 ± 5.4% (Fig. 3). Since this is the first paper to determine matrine’s absolute oral bioavailability in any species, no comparison was possible even though there were several papers publishing matrine pharmacokinetic studies in rats [6,7], beagle dogs [21] and humans [22]. On the other hand, Wu et al. found that approximatly 44% of matrine was absorbed by using a deconvolution method in a rat oral pharmacokinetic study at the dose of 40 mg/kg [7].

Because the current pharmacokinetic study suggested that matrine’s bioavailability is signficantly less than 44%, several possible reasons for its poor bioavailability were examined. One reason was that matrine could be accumulated in liver after oral administration especially after low oral dose. Gao et al. showed that matrine had a high tissue distribution in liver after oral administration (plasma:liver = 1:5) [1]. Another possible reason was that lower dose we used (2 mg/kg) may cause low bioavailability due to non-linear dose response. Lastly, matrine may have undergone first-pass metabolism in vivo.

We observed a relatively short t½ (2.3 and 1.5 h for i.v and oral dose respectively) in our pharmacokinetics result, although the difference between oral and iv administration was not significant (Fig. 3). The reported t½ of matrine from Wu et al. was 100–120 min [7], consistent with the current studies. But t½ of matrine was much longer in the report of Zhang et al. (9.75 h) [6]. The explanation was that pure matrine was given to rats in this study while an herb extract from Sophora flavescens Ait was given to rats in the study by Zhang et al. [6]. Oxymatrine is a major constituent in Sophora flavescens Ait extract and can be metabolized to matrine in vivo [6,21].

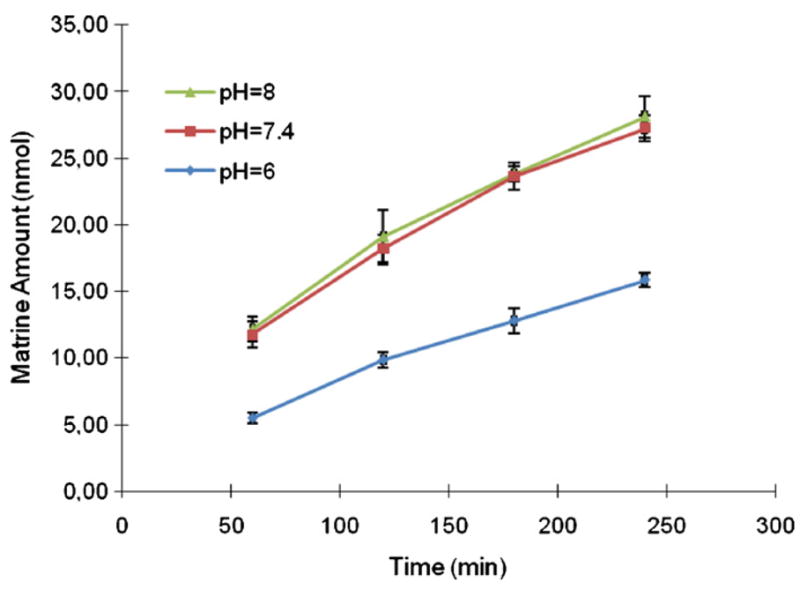

3.4. Transport of matrine across Caco-2 cell monolayer

The Caco-2 cell culture model is recognized by FDA as a useful model system to classify a compound’s absorption characteristics [9,10,16,23]. Caco-2 transport model was used to estimate the absorption characteristics of matrine using the same analytical method. Transport of 10 μM matrine from apical side to basolateral side (A–B) was firstly studied in the Caco-2 cell model at pH 7.4. The results showed that matrine had a high absorptive permeability (P = 42.5 × 10−6 cm/s >10−5 cm/s). This permeability did not change when the concentration was lowered to 1 μM (not shown). The permeability was decreased approximately 50% when pH was decreased to pH 6 but did not increase when pH was raised to pH 8 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect of different pH on transport of matrine across Caco-2 cell monolayer. Each data point is the average of three determinations and the error bar is the standard deviation of the mean.

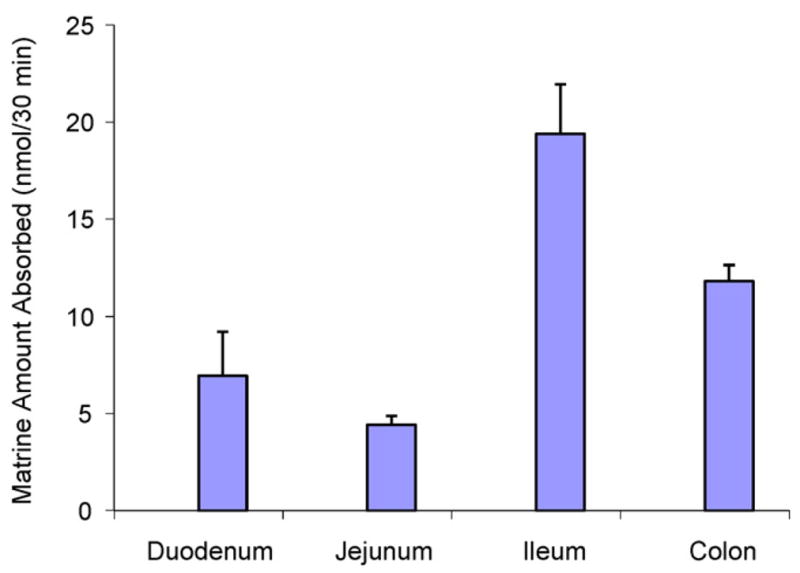

3.5. Regional absorption of matrine in the rat intestinal perfusion model

Rat intestinal perfusion model, an in situ model with intact circulation, is suitable to study regional intestinal absorption [11–13]. Therefore, rat intestinal perfusion model was used to investigate matrine absorption in situ because the perfusion model could more accurately reflect matrine absorption in rats [9,16]. The results showed that there were significant difference in the amounts of matrine absorbed in four segments of the intestine (Fig. 5). The amounts of matrine absorbed in ileum (34%, Pw = 6.18) and colon (21%, Pw = 2.07) were significantly higher (P < 0.01) than that in duodenum (12%, Pw = 0.61) and jejunum (7.8%, Pw = 0.52). The results showed that matrine had the highest permeability in ileum segment and lowest permeability in the jejunum segment.

Fig. 5.

Amounts of matrine absorbed in a four-site rat intestinal perfusion model (n = 3). Each bar is the average of three determinations and the error bar is the standard deviation of the mean.

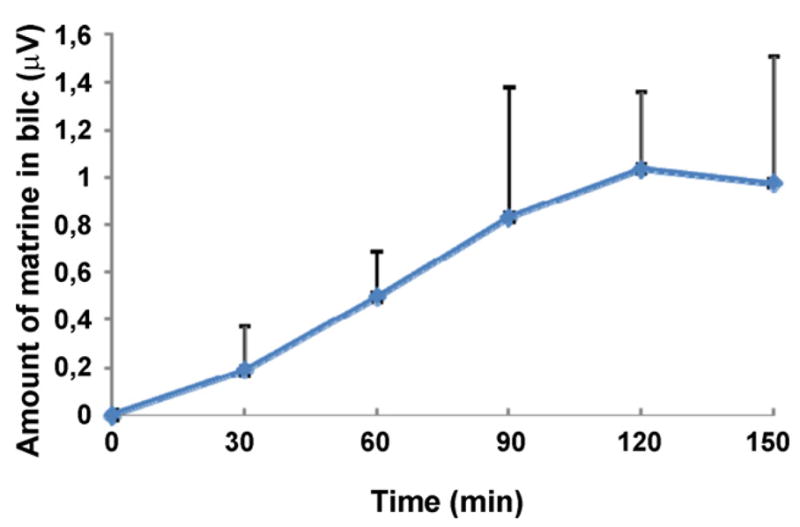

The amounts of matrine measured in bile sample were shown in Fig. 6. Based on an average of 0.5 ml per sample, the amount excreted was 0.5 nmol. The average amount absorbed from the intestine (all four segments added together) was about 45 nmol per 30 min. The amounts found in bile was about 1% of the absorbed amount, which is pretty small in comparison to dose absorbed.

Fig. 6.

Concentrations of matrine in bile sample in a four-site rat intestinal perfusion model (n = 3). The average volume of bile is 0.5 ml every 30 min, which means that at steady state conditione, a bile concentration of 1 μM will be equivalent to 0.5 nmol/30 min.

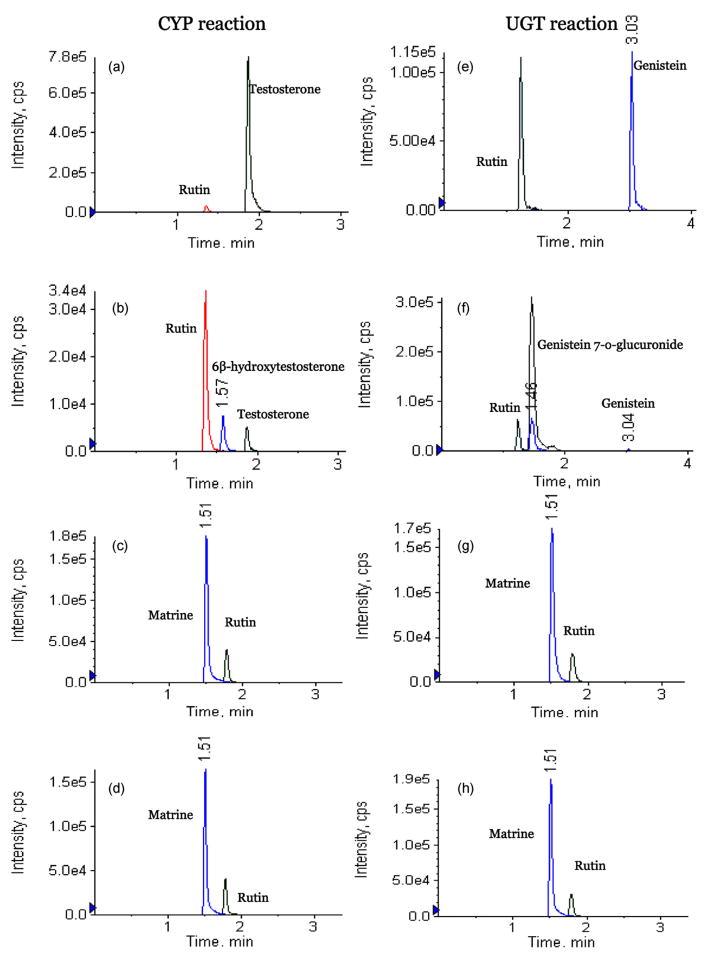

3.6. Metabolism of matrine in CYP and UGT reaction systems

In vitro metabolism could be used to determine whether matrine went through extensive first-pass metabolism in liver after oral administration. The results of matrine metabolism in rat liver microsomes studies showed that matrine could not be metabolized by CYP450 and UGT enzymes (Fig. 7), even though two positive control experiments showed that 10 μM testosterone (CYP control) and genistein (UGT control) had been thoroughly metabolized in the appropriate reaction systems (Fig. 7). Two positive controls, testosterone and genistein, were used in liver microsome study because they are well known substrates for CYP and UGT reaction, respectively [9,24]. These results suggested that matrine could not be extensively metabolized by CYP and UGT enzymes, which are two of the most common metabolism pathways. A review of data in literature showed that no metabolites of matrine were found in two previous studies [1,7], and this was consistent with our result.

Fig. 7.

Chromatograms of various CYP and UGT reaction substrates before and after incubation with rat liver microsomes for 1 h. The detector used was MS/MS and the methods were described in details in the Method section. (a) MRM chromatograms of testosterone after 1 h incubation in a CYP reaction system lacking NADPH (negative control); (b) MRM chromatograms of testosterone after 1 h incubation in a CYP reaction system; (c) MRM chromatograms of matrine after 1 h incubation in a CYP reaction system lacking NADPH (negative control); (d) MRM chromatograms of matrine after 1 h incubation in a CYP reaction system; (e) MRM chromatograms of genistein after 1 h incubation in a UGT reaction system lacking UDP-GA (negative control); (f) MRM chromatograms of genistein after 1 h incubation in a UGT reaction system; (g) MRM chromatograms of matrine after 1 h incubation in a UGT reaction system lacking UDP-GA (negative control); (h) MRM chromatograms of matrine after 1 h incubation in a UGT reaction system.

3.7. Solubility

Matrine is water soluble and it was completely dissolved in saline and oral suspension vehicle (>2 mg/ml). The determination of matrine in i.v dose and oral dose demonstrated that matrine were stable and uniform in saline and oral suspension vehicle for 3 months at −20 °C (data not shown). Therefore, this low bioavailability of matrine was not caused by its poor solubility.

4. Conclusion

A rapid, sensitive and specific UPLC–MS/MS method had been developed and successfully applied for analyzing matrine in aqueous media, rat intestine perfusate, rat bile, rat microsome, and plasma samples. The precision, extraction recovery, matrix effect and stability of this method had been validated. This is the first time that bioavailability of matrine after oral administration in rat is determined (17.1%). This is also the first paper to systematically characterize biopharmaceutical properties of matrine in Caco-2 transport model, in situ rat intestine perfusion model and rat microsomal model, which demonstrated the robustness of the current analytical method.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by NIH AT005522 to MH at University of Houston (Houston, TX) and to MY at Washington University (St. Louis, MO).

References

- 1.Gao G, Law FC. Physiologically based pharmacokinetics of matrine in the rat after oral administration of pure chemical and ACAPHA. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:884–891. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.023788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Z, Wang Y, Yao R, Li J, Yan Y, La Regina M, Lemon WL, Grubbs CJ, Lubet RA, You M. Cancer chemopreventive activity of a mixture of Chinese herbs (antitumor B) in mouse lung tumor models. Oncogene. 2004;23:3841–3850. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wan XY, Luo M, Li XD, He P. Hepatoprotective and anti-hepatocarcinogenic effects of glycyrrhizin and matrine. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;181:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai ZJ, Gao J, Ji ZZ, Wang XJ, Ren HT, Liu XX, Wu WY, Kang HF, Guan HT. Matrine induces apoptosis in gastric carcinoma cells via alteration of Fas/FasL and activation of caspase-3. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;123:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu XS, Jiang J. Molecular mechanism of matrine-induced apoptosis in leukemia K562 cells. Am J Chin Med. 2006;34:1095–1103. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X06004557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L, Liu W, Zhang R, Wang Z, Shen Z, Chen X, Bi K. Pharmacokinetic study of matrine, oxymatrine and oxysophocarpine in rat plasma after oral administration of Sophora flavescens Ait. extract by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2008;47:892–898. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu X, Yamashita F, Hashida M, Chen X, Hu Z. Determination of matrine in rat plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography and its application to pharmacokinetic studies. Talanta. 2003;59:965–971. doi: 10.1016/S0039-9140(03)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang XL, Xu HR, Chen WL, Chu NN, Li XN, Liu GY, Yu C. Matrine determination and pharmacokinetics in human plasma using LC/MS/MS. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009;877:3253–3256. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, Hu M. Absorption and metabolism of flavonoids in the caco-2 cell culture model and a perused rat intestinal model. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:370–377. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.4.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu M, Chen J, Tran D, Zhu Y, Leonardo G. The Caco-2 cell monolayers as an intestinal metabolism model: metabolism of dipeptide Phe-Pro. J Drug Target. 1994;2:79–89. doi: 10.3109/10611869409015895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu M, Roland K, Ge L, Chen J, Li Y, Tyle P, Roy S. Determination of absorption characteristics of AG337, a novel thymidylate synthase inhibitor, using a perfused rat intestinal model. J Pharm Sci. 1998;87:886–890. doi: 10.1021/js970251e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu ZQ, Jiang ZH, Liu L, Hu M. Mechanisms responsible for poor oral bioavailability of paeoniflorin: role of intestinal disposition and interactions with sinomenine. Pharm Res. 2006;23:2768–2780. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jia X, Chen J, Lin H, Hu M. Disposition of flavonoids via enteric recycling: enzyme-transporter coupling affects metabolism of biochanin A and formononetin and excretion of their phase II conjugates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:1103–1113. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.068403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu M, Sinko PJ, deMeere AL, Johnson DA, Amidon GL. Membrane permeability parameters for some amino acids and beta-lactam antibiotics: application of the boundary layer approach. J Theor Biol. 1988;131:107–114. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(88)80124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amidon GL, Sinko PJ, Fleisher D. Estimating human oral fraction dose absorbed: a correlation using rat intestinal membrane permeability for passive and carrier-mediated compounds. Pharm Res. 1988;5:651–654. doi: 10.1023/a:1015927004752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu M, Chen J, Lin H. Metabolism of flavonoids via enteric recycling: mechanistic studies of disposition of apigenin in the Caco-2 cell culture model. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:314–321. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu M, Krausz K, Chen J, Ge X, Li J, Gelboin HL, Gonzalez FJ. Identification of CYP1A2 as the main isoform for the phase I hydroxylated metabolism of genistein and a prodrug converting enzyme of methylated isoflavones. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:924–931. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.7.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, Halls SC, Alfaro JF, Zhou Z, Hu M. Potential beneficial metabolic interactions between tamoxifen and isoflavones via cytochrome P450-mediated pathways in female rat liver microsomes. Pharm Res. 2004;21:2095–2104. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000048202.92930.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang SW, Kulkarni KH, Tang L, Wang JR, Yin T, Daidoji T, Yokota H, Hu M. Disposition of flavonoids via enteric recycling: UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1As deficiency in Gunn rats is compensated by increases in UGT2Bs activities. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:1023–1031. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu XL, Hang TJ, Shen JP, Zhang YD. Determination and pharmacokinetic study of oxymatrine and its metabolite matrine in human plasma by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006;41:918–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Ma Y, Li X, Qin F, Lu X, Li F. Simultaneous determination and pharmacokinetic study of oxymatrine and matrine in beagle dog plasma after oral administration of Kushen formula granule, oxymatrine and matrine by LC–MS/MS. Biomed Chromatogr. 2007;21:876–882. doi: 10.1002/bmc.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang PQ, Lu GH, Zhou XB, Shen JF, Chen SX, Mei SW, Chen MF. Pharmacokinetics of matrine in healthy volunteers. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 1994;29:326–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu M, Chen J, Zhu Y, Dantzig AH, Stratford RE, Jr, Kuhfeld MT. Mechanism and kinetics of transcellular transport of a new beta-lactam antibiotic loracar-bef across an intestinal epithelial membrane model system (Caco-2) Pharm Res. 1994;11:1405–1413. doi: 10.1023/a:1018935704693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magnusson MO, Sandstrom R. Quantitative analysis of eight testosterone metabolites using column switching and liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:1089–1094. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]