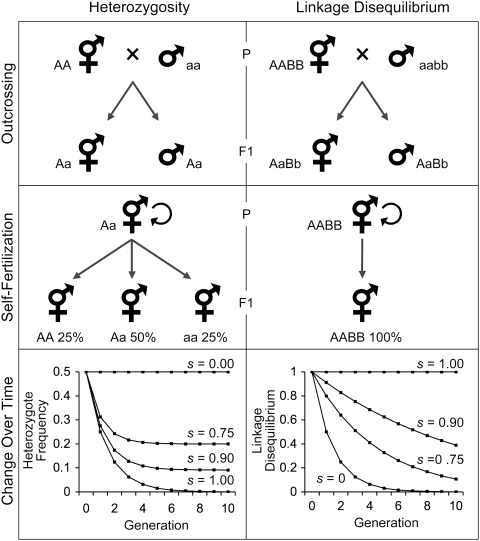

Figure 1.

Some genetic consequences of outcrossing and selfing. Left: outcrossing maintains heterozygosity, whereas self-fertilization creates an excess of homozygotes. Right: outcrossing can break linkage between alleles at different loci, whereas self-fertilization maintains linkage disequilibria over time. These patterns are generated by the coancestry within and between loci generated by selfing (middle) and are manifest within populations by changing levels of heterozygosity and linkage disequilibrium (bottom). Here, heterozygosity is determined by  , where s is the rate of self-fertilization and H0 is the initial heterozygosity before selfing (scaled here to its maximum value of 0.5; Crow and Kimura 1970). Linkage disequilibria at generation t are given by , where D0 is the amount of linkage disequilibrium at generation zero (scaled to 1.0 for convenience) and is the effective amount of recombination scaled by the rate of selfing within the population: (Nordborg 1997; Barrière and Félix 2005). The actual recombination rate, r, was set to 0.5 for this example.

, where s is the rate of self-fertilization and H0 is the initial heterozygosity before selfing (scaled here to its maximum value of 0.5; Crow and Kimura 1970). Linkage disequilibria at generation t are given by , where D0 is the amount of linkage disequilibrium at generation zero (scaled to 1.0 for convenience) and is the effective amount of recombination scaled by the rate of selfing within the population: (Nordborg 1997; Barrière and Félix 2005). The actual recombination rate, r, was set to 0.5 for this example.