Abstract

Studies of the spatio-temporal distribution of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) in a neuron have been limited by the spatial information that can be obtained by electrode recordings. We describe a method that overcomes these limitations by imaging IPSPs with voltage-sensitive dyes. CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons from brain slices were loaded with the voltage-sensitive dye JPW-1114 from a somatic patch electrode in whole-cell configuration. After removal of the patch electrode, we found that neurons recover their physiological intracellular chloride concentration. Using an improved voltage-imaging technique, dendritic GABAergic IPSPs as small as 1 mV could be resolved optically from multiple sites with spatial averaging. We analyzed the sensitivity of the technique, in relation to its spatial resolution. We monitored the origin and the spread of IPSPs originating in different areas of the apical dendrite and reconstructed their spatial distribution. We achieved a clear discrimination of IPSPs from the dendrites and from the axon. This study indicates that voltage imaging is a uniquely suited approach for the investigation of several fundamental aspects of inhibitory synaptic transmission that require spatial information.

Introduction

Fast inhibitory synapses use chloride (Cl−) permeable channels to generate inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) in different regions of the postsynaptic neuron (1). These signals, from different classes of interneurons, play various functional roles in the brain (2). The analysis of the spatial and temporal distribution of IPSPs in neuronal processes is therefore critical to understanding the mechanisms of inhibition. To carry out this analysis, one must measure IPSP signals from processes of individual neurons at high spatial resolution and under minimal perturbation of the intracellular Cl− concentration ([Cl−]i). Whereas standard electrode measurements do not provide adequate spatial resolution and also interfere with [Cl−]i, it became possible recently to successfully carry out multisite optical measurements of relatively large subthreshold excitatory synaptic potentials using voltage-sensitive dyes and signal averaging (3). In recording optically membrane potential signals from processes of individual neurons, the required sensitivity could be achieved only if single cells were stained selectively by diffusion of a voltage-sensitive dye from a patch electrode. The major challenge in extending this approach to the study of synaptic inhibition was to advance the sensitivity of recording to a level that would allow monitoring small amplitude IPSPs at the required spatial resolution. This critical improvement has been achieved by using single wavelength laser excitation at 532 nm in epi-illumination, wide-field microscopy mode.

Materials and Methods

Slice preparation and electrophysiology

Experiments, approved by Basel cantonal authorities, were done in 250 μm thick transversal slices of the hippocampus from 24–32 days old mice (C57BL/6), decapitated after isoflurane anesthesia (according to the Swiss regulation). Slices were prepared in ice-cold solution using a HM 650 V vibroslicer (Microm, Volketswil, Switzerland), incubated at 35°C for 40 min and maintained at room temperature. The solution used for slicing was the modified recording extracellular solution with reduced CaCl2 concentration (0.5 mM instead of 2 mM). Somatic whole-cell recordings were done using a Multiclamp 700A amplifier (Axon Instruments) and an upright microscope (Olympus BX51-WI). The recording extracellular solution contained (in mM): 125 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 20 glucose, 3 KCl, 1 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, and 1 MgCl2, pH 7.4 when bubbled with a gas mixture containing 95% O2, 5% CO2. The basic intracellular solution contained (mM): 5 Na-ATP, 0.3 Tris-GTP, 14 Tris-phosphocreatine, 20 HEPES, and either 125 KMeSO4, 5 KCl, or 90 KMeSO4, 40 KCl. Solutions were adjusted to pH 7.35 with potassium hydroxide. During whole-cell recordings, the real membrane potential was estimated after correcting for the junction potential (−11.0 mV for the 5 mM Cl− and −9.4 mV for the 40 mM Cl− intracellular solution calculated using JPCalc software (4)). Local stimulation of presynaptic fibers was carried out with patch pipettes filled with extracellular solution positioned under transmitted light using hydraulic manipulators (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). Somatic electrode recordings were acquired at 16 kHz and filtered at 4 kHz using the A/D board of the Redshirt imaging system.

Neuronal loading

Individual neurons were loaded with the voltage sensitive dye JPW-1114 (0.2–0.5 mg/mL) as described previously (5,6). The dye was purchased from Molecular Probes-Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Intracellular staining was accomplished by free diffusion of the dye from a patch-electrode. To avoid extracellular deposition of the dye and the resulting large background fluorescence, the tip of the electrode was filled with dye-free solution and the positive pressure was kept at the minimum before reaching the cell. For this study, we used 4–5 MΩ electrodes obtained by pulling borosilicate pipettes with 1.5 mm external diameter and 1.17 mm internal diameter without filament to a tip diameter of ∼1 μm. We back-filled the tip of these electrodes with dye-free solution using negative pressure from a 10 mL syringe for 10–20 s and we applied a positive pressure of ∼30 mbar for ∼10 s as measured with a manometer (Model 840081; Sper Scientific, Scottsdale, AZ) while approaching the cell in the slice. The patch electrode used for dye loading was attached to the neuron in whole-cell configuration for 25–30 min. The amount of staining was determined by measuring the resting fluorescence from the cell body at reduced excitation light intensity (∼0.1% of the laser light). The staining did not cause pharmacological effects (5–8). After loading was completed, the patch electrode was carefully detached from the cell by forming an outside-out patch. In the experiments where we needed to carry out measurements during the loading process the temperature was set to 32–34°C. Otherwise, loading at room temperature (24°C) resulted in better preservation of neurons in experiments that lasted for >2 h after loading termination.

Optical recording

Optical recordings were carried out by exciting the voltage-sensitive fluorescence with a 532 nm-300 mW solid state laser (model MLL532; CNI, Changchun, China). The laser beam was directed to a light guide coupled to the microscope via a single-port epifluorescence condenser (TILL Photonics GmbH; Gräfelfing, Germany) designed to overfill the back aperture of the objective. In this way, near uniform illumination of the object plane was attained. The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) in light intensity measurement is a linear function of the product of the relative fluorescence change (ΔF/F) in response to membrane potential changes and the square root of the resting florescence light intensity. Thus, compared to previous studies using the light from a xenon lamp filtered by a bandpass interference filter (525 ± 25 nm) (5,6), laser excitation improved the sensitivity of recordings, in terms of S/N in two ways. First, the ΔF/F for a given change in membrane potential is ∼2.5 times larger with the laser than with the lamp (see Supporting Material). Second, the excitation light intensity provided by the laser (as measured with a power meter from LaserCheck, Coherent, Santa Clara, CA) was >10 times higher than the excitation light intensity from the arc-lamp. In the shot-noise limited measurements, the higher excitation light intensity improves the S/N but also increases the probability of photodynamic damage. We kept the photodynamic damage under control by limiting the light intensity and the exposure time. We established that 6–12.5% of the full laser light output was sufficient to resolve Cl−-mediated synaptic potentials at 500 Hz. At this light level, it was possible to obtain 40–80 intermittent recording trials of 100 ms, separated by 30-s dark periods between consecutive exposures. In some measurements, we recorded action potentials and synaptic potentials at the frame rate of 2 kHz, using 25% full laser light output and 50 ms intermittent exposures separated by 1-min dark periods between consecutive exposures. In imaging action potentials signals in the axon at the frame rate of 10 kHz, we used the full laser light output and 25-ms exposures with 1-min dark periods between consecutive exposures. In experiments using 25–100% of the laser light, we limited the number of recording trials to the maximum of 10 to avoid possible phototoxic effects. Under these conditions, repetitive light exposures did not cause any detectable change in the kinetics of the action potential recorded electrically from the soma and optically from the dendrite (see Supporting Material).

Optical signals were captured with a high-speed, 80 × 80 pixels CCD camera NeuroCCD-SM (RedShirtImaging LLC, Decatur, GA). The excitation light was directed to a water immersion objective, either Olympus 60×/1.1 NA or Nikon 60×/1 NA (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The fluorescent image of the cell was projected via a 0.25× or a 0.1× optical coupler onto the CCD camera. Depending on optical magnification, the imaged field in our measurements was either ∼125 μm × 125 μm or ∼300 μm × 300 μm. The excitation light was directed to the preparation using a 570 nm dichroic mirror and the emission light was filtered with a 610 nm long-pass filter. Optical and electrophysiological recordings were done at 32–34°C. Recordings at frame rates of 0.5–2 kHz were done at full-frame readout (80 × 80 pixels). Recordings at 10 kHz were done at partial readout (80 × 12 pixels). Optical signals corresponding to GABAergic synaptic potentials were typically averages of 4–16 trials. Optical signals corresponding to action potentials were either single recording trials or averages of four trials.

Anatomical reconstruction and data analysis

Anatomical reconstruction of neurons was carried out from a stack of two-photon excitation fluorescence images obtained using a tunable, mode-locked titan-sapphire laser (MaiTai HP, Spectra Physics, Germany) set to 850 nm and a laser scanning system (FV300, Olympus Switzerland) with a high-aperture 20× water-immersion lens (Olympus LUMPLAN 20×).

Images and electrophysiological recordings were analyzed with dedicated software written in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). Optical signals were analyzed as fractional changes of fluorescence (ΔF/F). In this analysis, the ΔF/F decrease due to bleach was subtracted using one-exponential fits of trials without electrical stimulation. Results from t-tests were considered significantly different for p < 0.01. Supporting movies were done using Windows Movie Maker.

Results

Staining procedure and IPSP optical recordings

Individual CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons from mouse brain slices were loaded with the voltage sensitive dye JPW-1114 by diffusion from a patch-electrode as described previously (5,6). IPSPs were evoked by extracellular stimulation (5–20 μA, 100 μs duration) of presynaptic axons in the presence of AMPA receptor antagonist NBQX (10 μM) and NMDA receptor antagonist D-AP5 (50 μM). The polarity of an IPSP is determined by the Cl− reversal potential (VCl) as described by the Nernst equation:

| (1) |

where [Cl−]i and [Cl−]o are the intracellular and extracellular Cl− concentrations, R is the thermodynamic gas constant, T is the temperature, and F is the Faraday constant. Because the whole-cell recording involves dialysis of the cytoplasm with the solution in the patch pipette, the [Cl−]i shifts toward the Cl− concentration of the patch pipette. We used intracellular solutions containing either 40 or 5 mM Cl−. In the experiment shown in Fig. 1 A the cell was loaded with the voltage-sensitive dye from the patch electrode with the intracellular solution containing 40 mM Cl−, leading to VCl ∼ −31 mV. Thus, the Cl−-mediated synaptic potential evoked at the baseline potential of −84 mV and recorded with the somatic electrode during the loading period had large positive polarity (Fig. 1 A, top trace). Noticeably, the polarity of the Cl−-mediated synaptic potential was positive within seconds after establishing the whole-cell configuration. After the electrode was removed, the cell was left undisturbed for 30–60 min to allow for the diffusion of the dye into distal dendrites and possible [Cl−]i reequilibration. After this period, we recorded optically from the dendritic branches contained within an area of ∼125 μm × 125 μm (Fig. 1 A). The Cl−-mediated synaptic potential evoked by a ∼10 μA stimulus and recorded optically as the spatial average from all dendritic branches had negative polarity (Fig. 1 A, middle left trace), suggesting substantial reduction of the [Cl−]i after resealing of the neuron. To test for the stability of the resting membrane potential and the overall health of the cell, we repatched it with the same 40 mM Cl− containing intracellular solution without the dye. Application of the same stimulus evoked a synaptic potential, recorded optically from the dendrites and electrically from the soma, which, again, had positive polarity (Fig. 1 A, bottom left trace).

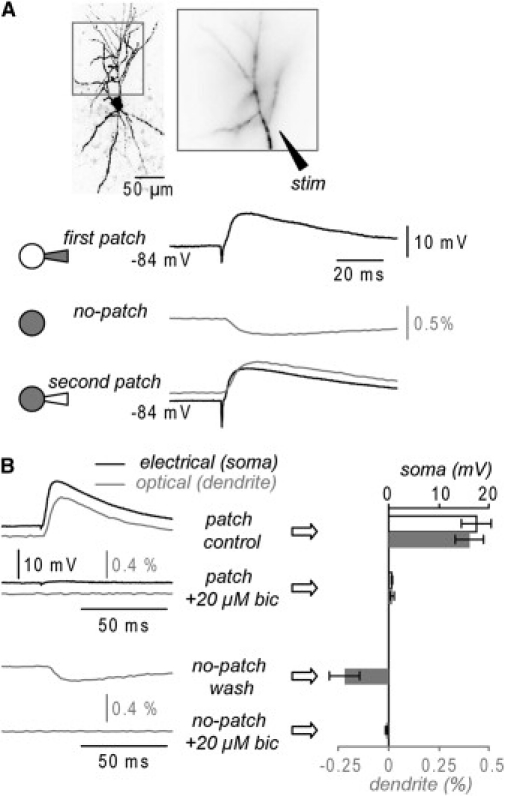

Figure 1.

Optical measurements of GABA-mediated synaptic potentials (A) (Top) Fluorescence image of a CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neuron (left). Dendritic region in recording position (right). (Upper trace) Electrical somatic recording (black) of a depolarizing evoked synaptic potential during dye loading with 40 mM Cl− internal solution (first patch). (Middle trace) Hyperpolarizing synaptic potential evoked by the same stimulus and recorded optically as spatial average from all dendrites after electrode removal (no-patch). (Bottom trace) Superimposed electrical somatic (black) and optical dendritic (gray) recordings of the synaptic potential after repatch with an electrode containing 40 mM Cl− (second patch). Synaptic potentials are averages of nine trials. (B) (Left/top) Electrical (black) and optical (gray) dendritic synaptic potential recordings during loading (40 mM Cl−) before and after addition of 20 μM bicuculline. (Left/bottom) optical dendritic recordings 30 min after patch termination and bicuculline washout before (upper trace) and after (lower trace) reapplication of bicuculline. (Right/top) Synaptic potential peak amplitude (mean ± SD; n = 5 cells) for electrical (white) and optical (gray) signals during loading before and after addition of 20 μM bicuculline. (Right/bottom) Optical synaptic potential signal peak amplitude (mean ± SD; n = 5 cells) after electrode removal before and after addition of bicuculline. Effects statistically significant (p < 0.01, paired t-test).

To confirm that the electrically and optically recorded synaptic potentials were mediated by GABAA receptors, somatic synaptic potentials were recorded with the patch electrode whereas the proximal part of the dendrite was monitored optically. In these recordings, made ∼20 min after the start of the staining procedure, both the electrical and the optical synaptic potentials signals were blocked by addition of 20 μM of the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline (Fig. 1 B, top traces). After electrode removal, bicuculline was washed out and the hyperpolarizing signal was recorded optically and blocked again in bicuculline solution (Fig. 1 B, bottom traces). The summary result from five experiments (Fig. 1 B, graph) shows that bicuculline effects were robust and statistically significant (p < 0.01 paired t-test).

Estimate of intracellular Cl− concentration ([Cl−]i) without use of electrodes

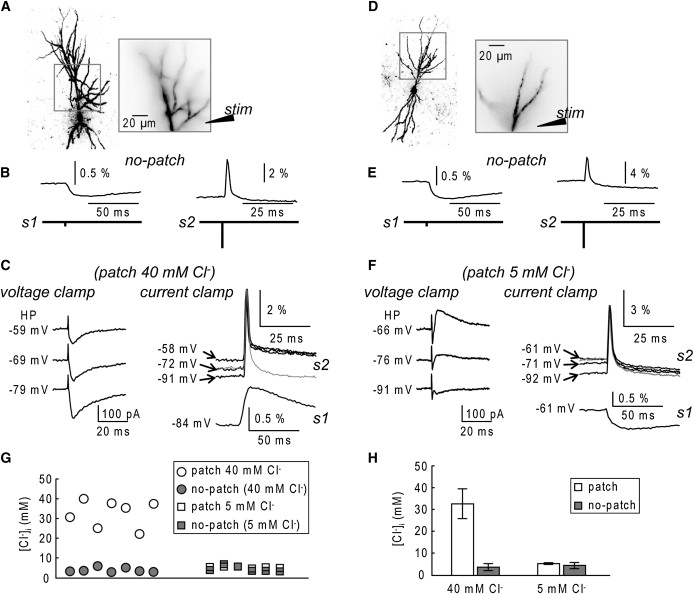

A critical requirement in studying synaptic inhibition is the preservation of the physiological gradient of Cl−. The substantial hyperpolarizing shift after resealing observed in experiments with high Cl− internal solutions indicates that the cells can restore a physiological Cl− homeostasis in a surprisingly short time. Our experiments therefore can provide not only a measurement of GABAergic potentials under physiological conditions, but also the direct measurement of the physiological [Cl−]i in the neuron. Thus, in a series of experiments, we investigated the effect of the staining protocol on the [Cl−]i in more detail. The change in the [Cl−]i after establishing the whole cell is very quick and we could not obtain a reliable estimate of the [Cl−]i from patch electrode measurements. Instead, we estimated the [Cl−]i without the use of electrodes with the procedure illustrated in Fig. 2. In the experiment shown in Fig. 2 A, the neuron was loaded with the voltage sensitive dye from an electrode containing 40 mM Cl-. After the electrode was removed, the cell was left undisturbed for 30 min to allow the diffusion of the dye into distal dendrites. We then optically recorded dendritic signals in response to extracellular stimulation, in the presence of glutamate receptor antagonists, at two different intensities. The weak stimulus (s1; 10 μA), evoked a hyperpolarizing synaptic potential signal as shown in Fig. 2 B (left trace). The strong stimulus (s2; ∼100 μA), excited the cell directly eliciting an action potential that was also recorded optically from the same dendritic area (Fig. 2 B, right traces). The evidence that an action potential could be evoked indicated that the resting membrane potential (Vrest) was below the firing threshold. Thus, a hyperpolarizing synaptic potential indicated that the corresponding [Cl−]i after the recovery period was much lower than the [Cl−]i during dye-loading. After these measurements, the neuron was repatched with the dye-free electrode containing 40 mM Cl− and the following sequence of measurements was carried out.

-

1.

We estimated VCl for the cell dialyzed with 40 mM Cl− solution (VCl(40 mM)) by linearly fitting the amplitude of the synaptic currents measured under voltage clamp at different holding potentials (Fig. 2 C, left traces, fit not shown).

-

2.

In current clamp configuration, the baseline membrane potential (BP) was set to a desired value, (−84 mV in the experiment shown in Fig. 2 C) and a synaptic potential was evoked by a weak stimulus (s1) and optically recorded from the dendritic area indicated in Fig. 2 A.

-

3.

In current clamp configuration, an action potential, evoked at BP levels using the strong extracellular stimulation (s2) was recorded optically from the same dendritic area. The amplitude of the optically recorded spike varied predictably as a function of BP (Fig. 2 C; top right traces) and, thus, could be used to estimate Vrest from optical recordings of spike signal amplitude in cells without an intracellular electrode.

Figure 2.

Optically recorded Cl−-mediated synaptic potentials are independent of the Cl− concentration in the patch pipette used for dye loading. (A) (Left) Fluorescence image of a CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neuron: intracellular solution for dye loading contained 40 mM Cl−. (Right) Dendritic region in recording position (∼125 μm × 125 μm, apical dendrite). (B) (Left) Cl−-mediated synaptic potential in response to low-intensity (s1) stimulation recorded optically (average of nine trials) after patch termination and after cell recovery obtained as the spatial average from all dendritic branches. (Right) Action potential signal evoked by high-intensity (s2) stimulation and recorded from the same area as the IPSP signal. (C) (Left) Synaptic currents under voltage-clamp obtained at different holding potentials during second recording with 40 mM Cl− internal solution. (Right) Optical recording of membrane potential signals under current-clamp conditions after s2 and s1 stimulations (second patch-electrode recording). (Upper traces) Action potential signals evoked at different baseline potentials. Gray trace is the action potential signal recorded before the patch-pipette was attached; estimated Vrest in B = −72 mV. (Lower trace) Response to s1 stimulations evoked at a baseline membrane potential of −84 mV. (D–F) Same as A–C for a cell dialyzed from an electrode with 5 mM Cl− intracellular solution; estimated Vrest in E = −61 mV. (G) Estimates of [Cl−]i plotted for neurons dialyzed from patch electrode containing 40 mM Cl− (n = 7) and 5 mM Cl− (n = 6). The values obtained after recovery period after patch-electrode removal are included. (H) Summary result (mean ± SD) for the data shown in G; The [Cl−]i after recovery period for two groups did not differ significantly (p = 0.38, two-populations t-test).

The membrane potential transient (ΔVm) corresponding to Cl−-mediated synaptic potential in an intact neuron is proportional to the driving force for Cl− and can be expressed as

| (2) |

where σ is a constant and VCl is unknown. If the neuron is dialyzed from the patch pipette, the [Cl−]i and the VCl are known and the expression becomes

| (3) |

Thus, the estimate of VCl and of the corresponding [Cl−]i can be obtained from the ratio of Eq. 2 and Eq. 3 without a need for intracellular electrode. This estimate is accurate under the assumption that [Cl−]i is uniform over the part of the neuron where the optical signal is spatially averaged. In the example of Fig. 2, A–C, the estimate of [Cl−]i was 30.68 mM with the patch electrode attached and 3.42 mM without patch electrode. In seven cells loaded with an internal solution containing 40 mM Cl−, the estimated intracellular Cl− concentration was 32.6 ± 6.8 mM (mean ± SD) with the patch electrode attached and 3.90 ± 1.15 mM without the patch electrode. To assess whether this value was independent of the Cl− concentration in the loading patch pipette, we repeated the same experiment using an internal solution containing 5 mM Cl−. The same sequence of measurements, as carried out for internal solution containing 40 mM Cl− (Fig. 2, A–C), is illustrated in Fig. 2, D–F. In six cells we found that [Cl−]i was 5.33 ± 0.37 mM with the patch electrode attached and 4.55 ± 1.40 mM without patch electrode (Fig. 2, G and H). The summary data showed that the values of [Cl−]i in neurons without attached patch electrode, obtained after dye-loading using an internal solution containing either 40 mM or 5 mM Cl−, were not different (p > 0.1, two-populations t-test). The results show that neurons restored their physiological [Cl−]i after dye loading from the patch pipette and that voltage imaging can be used to estimate this important biophysical parameter.

Resolution of optical IPSP measurements

The excellent S/N in the recordings shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 is typical for ∼10 mV synaptic potential signals averaged spatially over large portions of the dendritic arbor and further improved by temporal averaging of nine trials. For signals of this size, however, it was possible to obtain adequate S/N by averaging signals over 2–4 pixels, with a pixel size of 1.56 × 1.56 μm. In the example shown in Fig. 3 A, ΔF/F signals from regions 1–5 associated with an IPSP of ∼8 mV are reported. Each region is formed by two pixels and the signals were obtained by averaging nine trials.

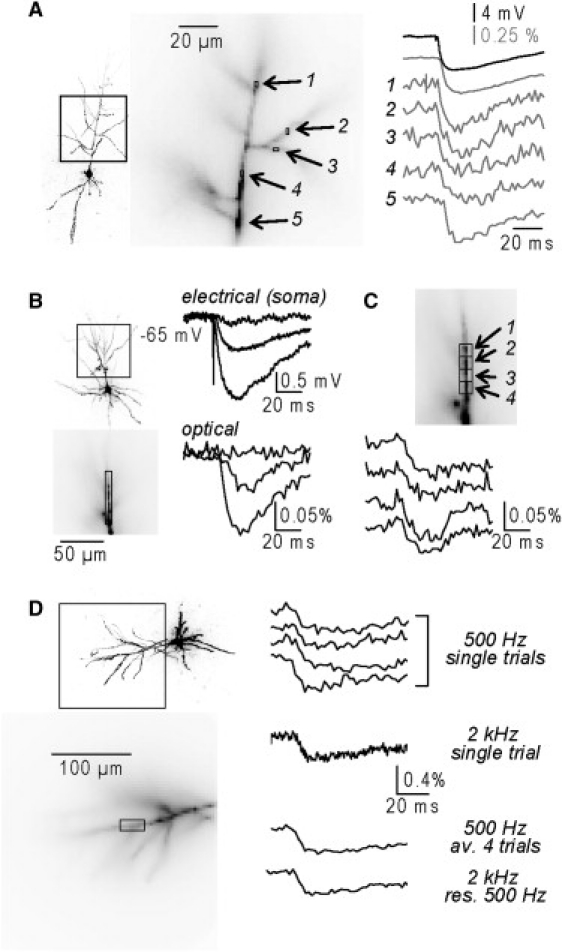

Figure 3.

Spatial resolution and sensitivity. (A) Fluorescence image of a neuron (left) and dendritic region in recording position (middle); regions 1–5 are ∼1.56 μm × 3.12 μm (2 pixels). (Right) Electrical somatic recording (black trace) and optical dendritic recordings (gray) of an IPSP ∼8 mV in amplitude from regions 1–5. Signals are averages of nine trials. (B) (Left) Image of a neuron (top) and apical dendrite in recording position (bottom); ∼75 μm long region of interest outlined. Right: electrical somatic recordings (top) and optical recording from the region of interest (bottom) of IPSPs ([Cl−]i∼5 mM) in response to three stimulus intensities (4 μA, 5 μA, and 10 μA). Signals are averages of 16 trials. Four μA stimulation fails to evoke an IPSP. Stimulations of 5 μA and 10 μA evoke IPSPs of ∼800 μV and ∼2 mV in amplitude respectively. (C) Optical recording of the ∼800 μV IPSP in B from the ∼6.5 μm long regions of interest 1–4. (D) (Left) Image of a neuron (top) and an apical dendrite in recording position (bottom); one region of interest indicated. (Right) Optical recordings from the region of interest; (top traces) four single trials recorded at 500 Hz at 6% of the laser power; (middle trace) a single trial recorded at 2 kHz at 25% of the laser power; (bottom traces) the average of the four trials at 500 Hz and the trial at 2 kHz resampled at 500 Hz.

IPSPs of 5–10 mV in amplitude shown above are typically associated with stimulation of more than one interneuron under physiological [Cl−]i. IPSPs of smaller amplitude, evoked by the stimulation of a single interneuron (unitary IPSPs), are still resolvable under our experimental conditions, but at a lower spatial resolution. The fluorescence intensity traces in Fig. 3 B (bottom traces) are averages of 16 trials from a set of pixels covering a length of ∼75 μm of the apical dendrite (Fig. 3 B, bottom image). The neuron was patched with an electrode containing 5 mM Cl− internal solution, approaching the physiological condition, so that the amplitude of the optically recorded IPSP in the very proximal dendrite could be calibrated using the electrical recording from the soma (Fig. 3 B, top traces). Three different stimulation intensities were tested. The weakest intensity failed to evoke an IPSP. The two higher intensities evoked IPSPs of ∼800 μV and ∼2 mV respectively. The results showed clearly that an IPSP of <1 mV in amplitude can be resolved at this spatial resolution (Fig. 3 B, bottom traces). The same signal could be still detected, but with a worse S/N, from regions 1–4, covering lengths of ∼6.5 μm (Fig. 3 C). In summary, by averaging 9–16 recordings, IPSPs of 1–2 mV and 5–10 mV can be reliably resolved with a spatial resolution of ∼50 μm and ∼2 μm, respectively.

The experiments shown above were carried out by illuminating the preparation with 6–12.5% of the total power of the laser. The S/N can be further improved by increasing the intensity of illumination while increasing the frame rate to avoid saturation of the CCD. In the experiments Fig. 3 D, IPSPs at a given stimulation intensity were first recorded at 500 Hz using 6% of the laser power and at 2 kHz using 25% of the laser power. Top traces in Fig. 3 D are ΔF/F signals, from the dendritic region indicated in the bottom image, corresponding to four trials recorded at a frame rate of 500 Hz and one trial recorded at a frame rate of 2 kHz. The average of four trials at 500 Hz has a S/N comparable to the single trial at 2 kHz resampled at 500 Hz (Fig. 3 D). The advantage of increasing the S/N by increasing the light is however counterbalanced by the increased photodynamic damage. Thus, fewer recordings can be done at stronger illumination intensity. As shown in the Supporting Material, the use of moderate illumination intensity (6–12.5%) allows for >40 recordings with no detectable photodynamic damage. The increased illumination is therefore especially advantageous in applications that require very short recording periods and few recordings.

Spatial distribution of IPSPs from different classes of interneurons

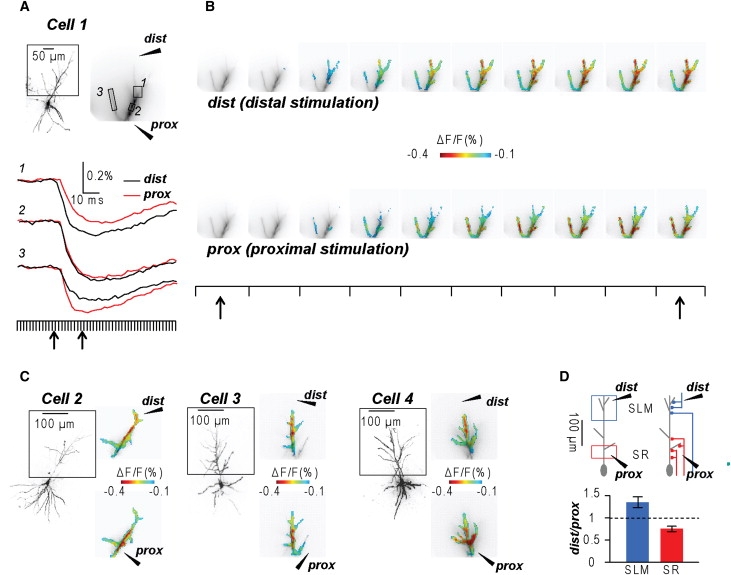

In the next series of experiments we compared the spatial distribution of IPSP signals evoked by localized electrical stimulation in different areas of the hippocampus. One stimulating electrode was positioned near the proximal part of the apical dendrite in the stratum pyramidale or in the stratum radiatum and another stimulating electrode in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare, at a distance of ∼300 μm from the soma. As predicted from morphological data, these two stimulations are likely to excite different subpopulations of interneurons (9–12). Indeed, stimulation in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare is likely to excite a subpopulation of interneurons that target pyramidal neurons distally from the soma whereas stimulation in the stratum pyramidale or in the stratum radiatum may excite cells that form contacts in different areas of the postsynaptic neuron (13). To compare IPSP signals from distal and proximal areas of the dendrite, we recorded from the larger field of view corresponding to the area of ∼300 μm × 300 μm in the object plane.

In the experiment shown in Fig. 4, A and B, the stimulating electrodes were positioned near the proximal part of the apical dendrite (prox) and distally, in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare (dist). The signals from three subcellular regions (Fig. 4 A, top right, locations 1–3), generated in response to extracellular stimulation via the two electrodes were analyzed and compared. In region 1 (distal area of the apical dendrite) the IPSP signal associated with distal stimulation was larger and with a faster rise than the IPSP signal associated with proximal stimulation (Fig. 4 A, traces). In contrast, in region 3 (proximal oblique dendrite) the IPSP signal was larger and with a faster rise for proximal stimulation than for distal stimulation. The two signals were nearly identical in the intermediate region 2. This result identified two distinct spatio-temporal patterns of IPSPs after stimulation of the two different hippocampal areas. This spatio-temporal pattern is shown Fig. 4 B and in Movie S1. The consistent difference in the spatial distribution of the IPSP related optical signal associated with distal and proximal stimulation is shown for three additional neurons as a color-coded map in Fig. 4 C. To quantify the spatial patterns of IPSPs after stimulation of the two different hippocampal areas, we analyzed ΔF/F signals over large dendritic regions >200 μm from the soma, mostly in the stratum lacunosum moleculare (SLM), and within 100 μm from the soma in the stratum radiatum (SR) (Fig. 4 D, left-drawing). In these two regions (SLM and SR), we calculated the ratio of the peak signals after distal and proximal stimulation (dist/prox). In six cells tested, the mean ± SE of this ratio was 1.35 ± 0.12 for the stimulus applied to SLM region, significantly different (p < 0.001, two-sample t-test) from the ratio calculated for the measurements after stimulation of the SR region (0.75 ± 0.06). These results show the ability of multisite optical recording to reliably detect specific spatial distribution of relatively small input signals on the dendritic arbor. In addition, they show that the spatial distribution of dendritic inhibition in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons is different for classes of interneurons that make contacts in the proximal and distal parts of the dendrite.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of IPSPs along the apical dendrite. (A) (Top) Image of a neuron with an area of ∼300 μm × 300 μm projected onto the CCD camera outlined; position of a distal (dist) and a proximal (prox) stimulating electrode shown schematically. (Bottom) Optical recordings of IPSPs evoked by dist (black) or prox (red) stimulation. Signals are averages of nine trials from locations 1–3. Frame sequence indicated below. (B) Sequence of frames between the two arrows in A showing a color-coded display of the spatio-temporal pattern of IPSP initiation and spread after distal and proximal stimulation. See Movie S1. (C) (Left) Images of three additional neurons analyzed. (Right) Spatial distribution of the IPSPs in the dendritic tree shown by color-coded representation of signal peak amplitude. The IPSP peak corresponds to red. (D) (Top left) Schematic drawing of a CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neuron with dist and prox stimulating electrodes. The location of two separate areas (SLM and SR) indicated by blue and red rectangles, respectively. (Top right) Schematic drawing of interneurons excited by dist and prox electrodes based on anatomical information. (Bottom) Mean ± SE of the ratio of peak signals associated with dist and prox stimulation from six cells. Values from SLM and SR regions are significantly different (p < 0.001, two-sample t-test).

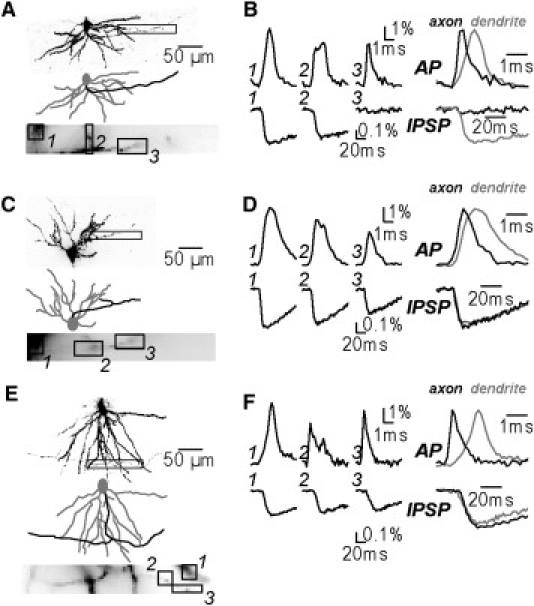

IPSP recordings from axons and basal dendrites

In another series of experiments we tested if IPSPs can be measured selectively from the axon. We recorded IPSP signals from the axon and from the neighboring basal dendrites, by monitoring regions of ∼125 μm X 125 μm in the stratum oriens. Imaging fluorescence from the initial segment of a CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neuron axon is complicated by the spatial overlap with dendrites. Thus, axonal signals can be contaminated by out-of focus fluorescence from the dendrites and vice versa. A way to discriminate between the two fluorescence sources is to image an action potential that in the axon is characterized by considerably faster kinetics compared to the dendritic action potential (8,14). In the three experiments shown in Fig. 5 the action potential signals recorded from locations 1 and 3 at a frame rate of 10 kHz had a single peak and kinetics that could be associated with the dendrite and with the axon respectively. In contrast, the action potential signal from location 2, exhibited two peaks suggesting that it was a mixture of axonal and dendritic signals. Similar results were obtained in all cells. Following these measurements, the IPSP signals evoked by stimulation in the stratum pyramidale were recorded from the same location and different results were obtained from different cells. In the experiment shown in Fig. 5, A and B, ΔF/F signals indicated clearly that the evoked IPSP was present in the dendrite (location 1) but absent in the axon (location 3; see also Movie S2). In the other two cells in Fig. 5, C–F, and in additional two neurons (not shown) the evoked IPSP was detected both in the dendrite and in the axon. Because it is well established that the charge-shift voltage-sensitive dye used here tracks the membrane potential precisely, different results obtained in different neurons suggest that different types of interneurons were stimulated in different experiments. These recordings unambiguously show the possibility to analyze in detail the spatial segregation of IPSPs from identified functionally different regions of the neuron.

Figure 5.

IPSPs recorded simultaneously in the axon and in the basal dendrite. (A) Image of a part of a CA1 pyramidal neuron in the stratum oriens with drawing of basal dendrites (gray) and axon (black). Part of a neuron projected onto a subset of pixels of the CCD camera for voltage-imaging (bottom image). Three recording locations are labeled 1–3. (B) (Left traces) Optical signals associated with an evoked action potential (top) and an IPSP (bottom) from locations 1–3 shown in C; location 1: dendritic signal; location 2: mixed signal; location 3: axonal signal. (Right traces) Optical signals from location 1 (dendrite, gray trace) and location 3 (axon, black trace) normalized in amplitude and superimposed. Action potential signal is present in the axon and in the dendrite. IPSP signal is absent in the axon (see also Movie S2). (C and E and D and F) Same sequence of measurements as in A and B from two additional neurons; IPSP observed both in the dendrite and in the axon. Action potential and IPSP signals were averages of 4 and 16 trials, respectively.

Discussion

The study of GABAergic signals is particularly challenging because these signals are generally small and localized to distinct areas of the neuron. Therefore, a new technique is needed for monitoring small changes of membrane potential with high spatial resolution. Direct patch clamp recordings provide high sensitivity and high temporal resolution, but poor spatial resolution. This limitation is critical in many studies. In addition, the dialysis of neurons with electrode solutions may introduce substantial distortions in the electrical behavior of target structures. These limitations are overcome by the described optical methodology that permits multiple site measurements of voltage signals from relatively small portions of dendrites and axons. We have shown here that illumination with stable solid state lasers, the use of high numerical aperture lenses, and detection with fast and large well capacity CCD cameras currently provide optimal conditions for these measurements.

The ions mediating the response of GABAA receptors, Cl− and bicarbonate, and therefore the polarity and the size of GABAergic synaptic potentials vary during development (15,16). The technique of perforated patch recording using gramicidin (17,18), that introduces negligible perturbation to the physiological [Cl−]i, has been used to show the presence of subcellular gradients of Cl− resulting in GABAergic synaptic potentials of different polarity (19–21). This method, however, lacks the spatial resolution necessary to record synaptic potentials at the site of origin. In contrast, voltage imaging seems to be an uniquely suited technique to investigate local inhibitory signals and a tool to provide reliable estimates of physiological [Cl−]i. The evidence that after termination of patch recordings cells recovered to a low Cl− concentration within minutes indicates that functioning transporter systems can restore physiological conditions. In our experiments, all the responses we measured were hyperpolarizing, regardless of the subcellular location or of the site of stimulation. This important result suggests that [Cl−]i is low in all areas of mature CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons confirming the conclusions from another study where noninvasive techniques were used (22). In addition, our results show the ability of multisite optical recording to consistently detect specific spatial distribution of IPSP input signals in the dendritic arbors and in the axon. This kind of information, uniquely available from high spatial resolution optical recordings, will likely facilitate further studies of the role of inhibition in determining the input-output transform carried out by individual nerve cells.

In summary, we believe this study shows a significant advance in the sensitivity of voltage imaging allowing detection of ∼1 mV IPSP signals at multiple subcellular sites. This approach overcomes important limitations of electrode measurements opening the gate to the spatial analysis of synaptic inhibition from individual nerve cells. The spatial distribution of IPSPs at physiological [Cl−]i can be now investigated in many other types of neurons using the experimental protocols presented here. A current limitation is the use of extracellular stimulation that, in general, precludes the precise identification of the stimulated interneurons and of the postsynaptic area where synaptic contacts are formed. Future work must overcome this limitation by coupling voltage imaging with selective presynaptic stimulation.

Supporting Material

References, one figure, and two movies are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(10)00157-8.

Supporting Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the University of Basel, the Swiss National Science Foundation (3100A0_122000 to M.C. and 3100A0-118352 to K.V.), and by the Swiss National Science Foundation travel grant IZKOBO-121641 to D.Z.

Footnotes

Marco Canepari's present address is Research Group 3, Calcium Channels, Functions, and Pathologies, Unité Inserm 836, Grenoble Institute of Neuroscience, Site Santé, BP 170, 38042 Grenoble cedex 09, France.

Contributor Information

Marco Canepari, Email: marco.canepari@unibas.ch.

Kaspar E. Vogt, Email: kaspar.vogt@unibas.ch.

References

- 1.Somogyi P., Klausberger T. Defined types of cortical interneurone structure space and spike timing in the hippocampus. J. Physiol. 2005;562:9–26. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.078915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mody I., Pearce R.A. Diversity of inhibitory neurotransmission through GABA(A) receptors. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Djurisic M., Antic S., Zecevic D. Voltage imaging from dendrites of mitral cells: EPSP attenuation and spike trigger zones. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:6703–6714. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0307-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry P.H. JPCalc, a software package for calculating liquid junction potential corrections in patch-clamp, intracellular, epithelial and bilayer measurements and for correcting junction potential measurements. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1994;51:107–116. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canepari M., Djurisic M., Zecevic D. Dendritic signals from rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons during coincident pre- and post-synaptic activity: a combined voltage- and calcium-imaging study. J. Physiol. 2007;580:463–484. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.125005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canepari M., Vogt K., Zecevic D. Combining voltage and calcium imaging from neuronal dendrites. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2008;58:1079–1093. doi: 10.1007/s10571-008-9285-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antic S., Major G., Zecevic D. Fast optical recordings of membrane potential changes from dendrites of pyramidal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1999;82:1615–1621. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.3.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer L.M., Stuart G.J. Site of action potential initiation in layer 5 pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:1854–1863. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4812-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vida I., Halasy K., Buhl E.H. Unitary IPSPs evoked by interneurons at the stratum radiatum-stratum lacunosum-moleculare border in the CA1 area of the rat hippocampus in vitro. J. Physiol. 1998;506:755–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.755bv.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price C.J., Cauli B., Capogna M. Neurogliaform neurons form a novel inhibitory network in the hippocampal CA1 area. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:6775–6786. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1135-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buhl E.H., Halasy K., Somogyi P. Diverse sources of hippocampal unitary inhibitory postsynaptic potentials and the number of synaptic release sites. Nature. 1994;368:823–828. doi: 10.1038/368823a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuentealba P., Begum R., Klausberger T. Ivy cells: a population of nitric-oxide-producing, slow-spiking GABAergic neurons and their involvement in hippocampal network activity. Neuron. 2008;57:917–929. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klausberger T., Somogyi P. Neuronal diversity and temporal dynamics: the unity of hippocampal circuit operations. Science. 2008;321:53–57. doi: 10.1126/science.1149381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shu Y., Duque A., McCormick D.A. Properties of action-potential initiation in neocortical pyramidal cells: evidence from whole cell axon recordings. J. Neurophysiol. 2007;97:746–760. doi: 10.1152/jn.00922.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherubini E., Gaiarsa J.L., Ben-Ari Y. GABA: an excitatory transmitter in early postnatal life. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:515–519. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90003-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivera C., Voipio J., Kaila K. Two developmental switches in GABAergic signaling: the K+-Cl− cotransporter KCC2 and carbonic anhydrase CAVII. J. Physiol. 2005;562:27–36. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.077495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhee J.S., Ebihara S., Akaike N. Gramicidin perforated patch-clamp technique reveals glycine-gated outward chloride current in dissociated nucleus solitarii neurons of the rat. J. Neurophysiol. 1994;72:1103–1108. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.3.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kyrozis A., Reichling D.B. Perforated-patch recording with gramicidin avoids artifactual changes in intracellular chloride concentration. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1995;57:27–35. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)00116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gulledge A.T., Stuart G.J. Excitatory actions of GABA in the cortex. Neuron. 2003;37:299–309. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szabadics J., Varga C., Tamás G. Excitatory effect of GABAergic axo-axonic cells in cortical microcircuits. Science. 2006;311:233–235. doi: 10.1126/science.1121325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khirug S., Yamada J., Kaila K. GABAergic depolarization of the axon initial segment in cortical principal neurons is caused by the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter NKCC1. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:4635–4639. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0908-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glickfeld L.L., Roberts J.D., Scanziani M. Interneurons hyperpolarize pyramidal cells along their entire somatodendritic axis. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:21–23. doi: 10.1038/nn.2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.