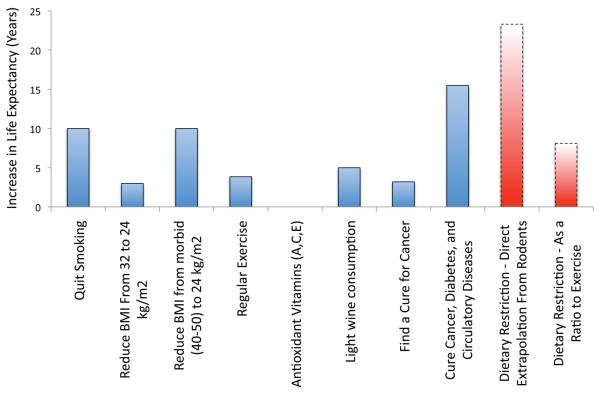

Figure 1.

Estimates of the effects of various interventions on human life expectancy. Note that data from unrelated studies on different populations are combined in this figure. The indicated effect for smoking is based on quitting at the age of 30, although there is a significant benefit to quitting even at advanced ages (Doll et al., 2004; Taylor et al., 2002). The estimated effects of body mass index (BMI) are based on observational studies, and may not accurately reflect the consequences of deliberate weight loss (Whitlock et al., 2009). The effect of exercise compares the highest tertile of physical activity to the lowest based on assessments conducted after the age of 50 years (Franco et al., 2005; Jonker et al., 2006). Vitamins A and E may actually be associated with increased mortality (Bjelakovic et al., 2008). Light wine consumption was defined as less than half a glass per day (Streppel et al., 2009). Only males were included in the study, and life expectancy was calculated at age 50. Of the 5-year increase, 2 years were attributed to alcohol per se, while 3 years were attributed to other components of wine, such as polyphenols (including resveratrol). Effects of disease cures are the estimates of Olshansky et al (Olshansky et al., 1990). Extrapolation of the effect of dietary restriction was based on a 30% increase in mean lifespan, which is typical of rodent studies (Weindruch et al., 1986), and the current Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimate of life expectancy in the US, 77.7 years. The influence of exercise appears to be greater in rodents than in humans, and this could reflect an inherent difference in the plasticity of lifespan between species. Therefore an alternate approach to estimating the effect of DR in humans is to assume it will be ~2.1 times as effective as exercise, as was the case for rats, albeit at a sub-optimal level of DR (Holloszy et al., 1985). Note that lifestyle changes, particularly the effects of smoking and obesity, are relevant to only a subset of the population. Thus, the changes in individual life expectancy presented here overestimate the potential impact of these interventions on average human lifespan.