Abstract

Objective

Damaged articular cartilage does not heal well and can progress to osteoarthritis (OA). Human bone marrow stem cells (BMC) are promising cells for articular cartilage repair, yet age- and sex-related differences in their chondrogenesis have not been clearly identified. The purpose of this study is to test whether the chondrogenic potential of human femoral BMC varies based on the sex and/or age of the donor.

Design

BMC were isolated from 21 males (16–82 y.o.) and 20 females (20–77 y.o.) during orthopaedic procedures. Cumulative population doubling (CPD) was measured and chondrogenesis was evaluated by standard pellet culture assay in the presence or absence of TGFβ1. Pellet area was measured, and chondrogenic differentiation was determined by Toluidine Blue and Safranin O-Fast Green histological grading using the Bern score and by glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content.

Results

No difference in CPD was observed due to donor sex or age. The increase in pellet area with addition of TGFβ1 and the Bern score significantly decreased with increasing donor age in male BMC, but not in female BMC. A significant reduction in GAG content per pellet was also observed with increasing donor age in male BMC. This was not observed in female BMC.

Conclusions

This study showed an age-related decline in chondroid differentiation with TGFβ1 stimulation in male BMC, but not in female BMC. Understanding the mechanisms for these differences will contribute to improved clinical use of autologous BMC for articular cartilage repair, and may lead to the development of customized age- or sex-based treatments to delay or prevent the onset of OA.

Keywords: bone marrow cells, chondrogenesis, differentiation, age, sex, cartilage repair

Introduction

Articular cartilage is an avascular tissue with limited intrinsic healing capacity. Due to its inability to heal efficiently, focal cartilage injuries of the knee have an increased risk of progressing to osteoarthritis (OA), a leading cause of disability [1]. Current treatment modalities for articular cartilage repair include debridement, osteochondral grafting, autologous chondrocyte implantation, and microfracture [2–4]. While good to excellent clinical outcome scores have been reported for each technique, the repaired cartilage is biomechanically dissimilar to the surrounding native cartilage. This can lead to degradation of the cartilage over time, which would set the stage for the progression of OA. Thus, there is an urgent need to improve articular cartilage repair, as it may delay, or even prevent the onset of debilitating OA.

Microfracture is minimally invasive and the simplest of the treatment techniques, as it involves penetrating the subchondral bone to access repair cells from the bone marrow to infiltrate the defect. Microfracture is, however, inconsistent [4–6]. A high degree of variability in the amount of repair cartilage that fills the defect has been reported, indicating that there may be a subpopulation of patients that do not produce sufficient repair tissue after microfracture, leading to early failure [4]. Age has also been shown to affect the clinical outcome of microfracture, with younger patients (<40 years old) showing better clinical outcome scores [6]. Since bone marrow cells are the main repair cells recruited to the defect during microfracture, it suggests an important and continued role for the autogenous application of bone marrow stem cells (BMC) in articular cartilage repair. The variability seen in clinical outcome measures suggests that BMC from different individuals could differ in their capacity for chondrogenic differentiation.

While it has been well established that BMC are capable of chondrogenic differentiation in vitro and in vivo [7–15], few studies have focused on comparing the chondrogenesis of BMC obtained from a large number of individuals [10, 11, 13]. This comparison is important to determine whether there is inherent variability at the BMC level between individuals for chondrogenic repair, so that this can be taken into account to develop efficient BMC-based therapies for articular cartilage repair. Since OA and injuries to articular cartilage affect men and women of all ages, it is important to determine whether the chondrogenic capacity of BMC differs based on the sex and/or age of the donor. Sexual dimorphism in the prevalence of OA has been reported, with women being diagnosed more frequently than men, especially over the age of 50 [1, 16]. Recent studies have shown that cell sex can affect the differentiation potential of both mouse and human progenitor cells [17–20]. As well, aging has been shown to affect the osteogenic differentiation of BMC [21–23], although this was not conclusive in all studies [24–26]. Our understanding of age- and sex-related differences in the chondrogenic capacity of BMC has not been clearly defined.

Cells isolated from bone marrow procured from the distal femur are promising cells for articular cartilage repair, since this site could be accessed as an autologous cell source, and these cells are similar to those typically accessed during microfracture. Sex- and age-related differences in the chondrogenic potential of femoral BMC should be investigated to better develop BMC-based therapies for articular cartilage repair. Such studies may also provide information predictive of the outcome of microfracture, which may affect patient selection and treatment chosen. For this reason, this study was performed to test the hypothesis that the chondrogenic potential of femoral human BMC varies based on the sex and/or age of the donor. The findings obtained will be important to improving articular cartilage repair, a strategy for potentially delaying the onset of disabling OA.

Methods

Cell isolation and expansion

Femoral bone marrow reamings were obtained from males and females undergoing orthopaedic surgery for fracture stabilization or joint replacement according to an exempt IRB-approved protocol at the University of Pittsburgh for discarded tissue. A total of 41 femoral bone marrow reamings were obtained. The donors ranged in age from 16 to 82 years old and included 21 males (16 to 82, mean donor age 39 ± 22) and 20 females (20 to 77, mean donor age 53 ± 17). Freshly harvested bone marrow was minced, washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and vortexed. The cell suspension was then passed through a 70 μm cell strainer. Thirty-five milliliters of cell suspension was loaded onto 15 ml Histopaque®-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo., USA) and fractioned by centrifugation (400 × g) for 30 minutes. Mononucleated cells were recovered from the Histopaque-supernatant interface and cultured in α-MEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 16.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; lot selected for rapid growth of BMC, Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA, USA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen). Cells were allowed to adhere for 5–7 days at 37°C and 5% CO2 before the first medium change, which would remove any non-adherent cells. Visible colonies were seen after 8–10 days of initial plating and were detached from the tissue culture plastic with 0.25% trypsin (Invitrogen). BMC were replated at 100 cells/cm2, trypsinized when they reached 70% confluence, and either used for experiments or replated at the same cell density for further expansion. Medium was refreshed every 3–4 days.

Cumulative population doublings

At passage 2, cells were placed in a T25-flask at a density of 100 cells/cm2. After 7 days, cells were trypsinized, counted, and replated at 100 cells/cm2. This was repeated until passage 8. Population doubling was calculated as the log2 (N/No), where No and N are the number of cells originally plated and the number of cells at the end of the expansion, respectively.

Chondrogenic differentiation

Chondrogenesis was tested on BMC at passage 3 or 4 using a previously described pellet culture assay [8]. A total of 2.5 × 105 cells were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 minutes in 15-ml conical polypropylene tubes. The cell pellets were cultured in 0.5 ml chondrogenic medium (CM) that contained high-glucose DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 10−7 M dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 μg/ml L-ascorbic acid-2-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich), 40 μg/ml proline (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA), and 1% BD™ ITS+Premix (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), in the presence or absence of TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). All pellets were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 21 days, and the CM was refreshed every 2–3 days.

Area measurement of pellets

After 21 days of culture, macroscopic images of the pellets were captured using a stereomicroscope (MVX-10 MacroView Systems, Olympus, Japan) equipped with a DP71 camera (Olympus), and the area was calculated using DP2-BSW software (Olympus). The change in pellet area was calculated by dividing the area measurement of pellets cultured in CM + TGFβ1 by that of pellets cultured in CM only.

Histological analysis

Pellets were fixed in 10% buffered formalin followed by paraffin embedding. Cross-sections (6 μm thick) were stained with Toluidine Blue for sulfated polysaccharides and Safranin O-Fast Green for sulfated glycosaminoglycans (GAG). Standard protocols for each of these stains were followed. Images were captured with DP2-BSW software (Olympus) using a Nikon TE-2000U Eclipse microscope equipped with a DP71 camera (Olympus). Safranin O-Fast Green histology was graded by two blinded observers using the Bern score [27]. Table 1 indicates the criteria used to grade Safranin O-Fast Green staining of pellets according to the Bern score.

Table 1.

The Bern Score: For the Evaluation of Safranin O-Fast Green Stained Cartilagenous Pellet Cultures (Minimum Score: 0; Maximum Score: 9)

| Scoring categories | Score |

|---|---|

| Category A: Uniformity and darkness of Safranin O-Fast green stain (10X objective) | |

| No stain | 0 |

| Weak staining of poorly formed matrix | 1 |

| Moderately even staining | 2 |

| Even dark stain | 3 |

| Category B: Distance between cells/amount of matrix accumulated (20X objective) | |

| High cell densities with no matrix in between (no spacing between cells) | 0 |

| High cell densities with little matrix in between (cells <1 cell-size apart) | 1 |

| Moderate cell density with matrix (cells approx. 1 cell-size apart) | 2 |

| Low cell density with moderate distance between cells (>1 cell) and an extensive matrix | 3 |

| Category C: Cellular morphologies represented (40X objective) | |

| Condensed/necrotic/pycnotic bodies | 0 |

| Spindle/fibrous | 1 |

| Mixed spindle/fibrous with rounded chondrogenic morphology | 2 |

| Majority rounded/chondrogenic | 3 |

Source: 27Grogan SP. et al., Tissue Eng 2006; 12(8):2141–9.

Biochemical analysis

To measure total GAG content from BMC pellets, pellets cultured for 21 days were washed with PBS and each dry pellet was frozen at −80°C until all pellets were ready to be assayed. Each frozen pellet was placed in 0.2 ml papain buffer [50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5), 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM cysteine HCL and 0.5 mg/ml papain] in a 60°C water bath overnight. The pellets were then vortexed and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 21,000 × g at room temperature. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, followed by GAG quantification. GAG was quantified using the standard dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) assay [28] with shark chondroitin-6-sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich) as the standard.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean ± SEM and analyzed using SPSS software version 17.0. Comparisons between 2 groups were performed using unpaired t-tests. Linear regression was performed to model the effect of age and/or sex on all measured outcomes (pellet area change, histological grading using the Bern score, and GAG content). P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Isolation and expansion of BMC

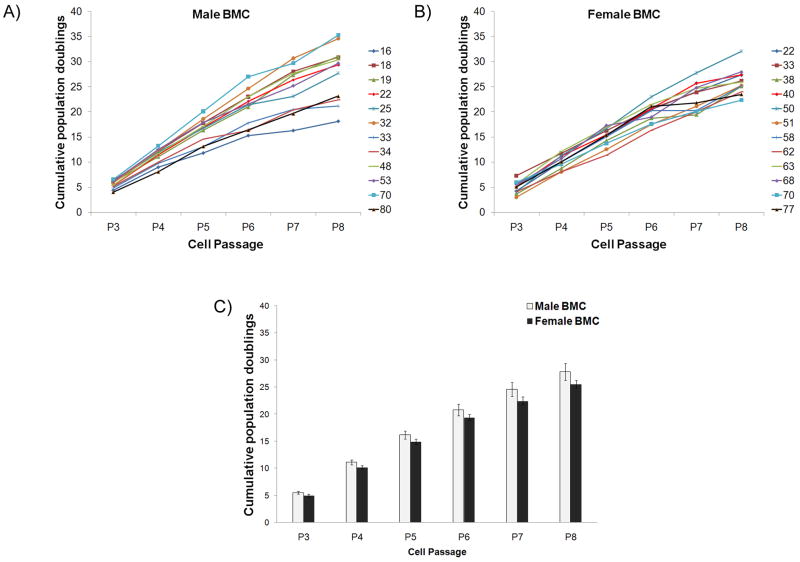

Mononuclear cells were obtained from all bone marrow specimens. Cell colonies were visible 8 to 10 days after initial plating, at which time the cells were trypsinized for the first time. The average cell yield (% of cells that adhered to tissue-culture plastic from the total number of mononuclear cells originally in flask) for males was 6.76 ± 2.37% and that for females was 7.36 ± 1.57%. No difference was observed based on donor age. The ability of the isolated BMC to be expanded in culture over several passages was investigated by plating them at 100 cells/cm2 followed by trypsinization and counting every 7 days, for a total of 8 passages. All populations tested were capable of expansion up to Passage 8 (Fig. 1A, B, numbers in legend indicate donor age). From the data presented in Figures 1A and 1B, the proliferation rate of BMC was found to be independent of bone marrow donor age. The expansion up to passage 8 results in 27.83 ± 1.57 cumulative population doublings per initial male BMC and 25.56 ± 0.70 cumulative population doublings per initial female BMC (Fig. 1C). No statistically significant difference was observed between males and females at all passages.

Figure 1. Cumulative population doublings of male and female BMC.

(A) Cumulative population doublings of male and (B) female BMC from Passage 3 to 8. Numbers in the graph legend represent the age of the bone marrow donor. (C) The average cumulative population doublings for male and female BMC from Passage 3 to 8. n=12 male BMC and 12 female BMC.

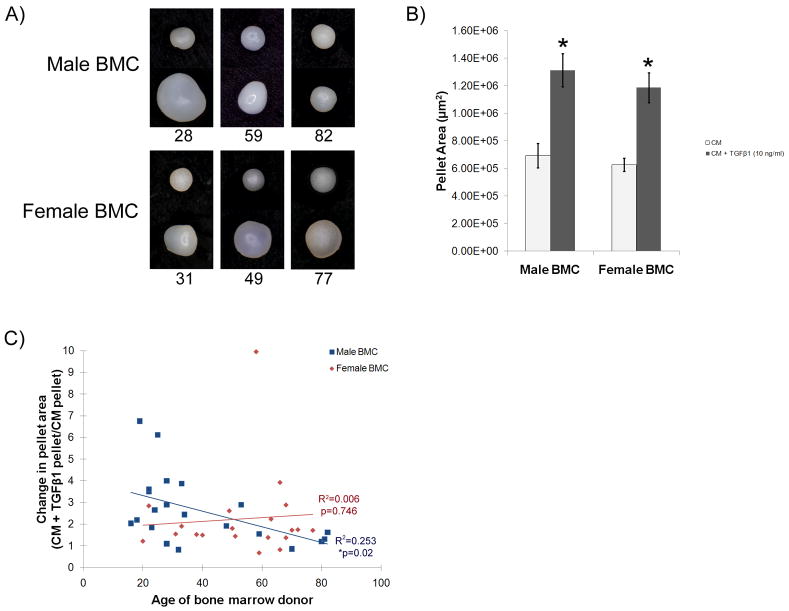

Change in pellet area in response to TGFβ1

Macroscopic images of the BMC pellets were taken after 21 days of culture in CM in the presence or absence of TGFβ1 (Fig. 2A, top row of Male BMC panel and Female BMC panel includes representative pellets cultured in CM, and bottom row of each panel shows representative pellets cultured in CM + TGFβ1). An increase in pellet size was evident with the addition of TGFβ1 to the CM for all female BMC shown. The increase in pellet size with addition of TGFβ1 was less evident with increasing age in the male BMC pellets shown (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Macroscopic appearance of BMC pellets and change in pellet area with addition of TGFβ1.

(A) Macroscopic images of representative male and female BMC pellets cultured in CM (top row) or CM + TGFβ1 (bottom row) for 21 days. Numbers below the image indicate the age of the bone marrow donor. (B) Pellet area measured from the macroscopic images of male and female BMC pellets cultured in CM and CM + TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml). *p<0.05 compared to CM. (C) Change in pellet area due to addition of TGFβ1 to CM for all populations tested. Male BMC showed a decrease in pellet area change with increasing donor age (R2= 0.253, *p=0.02), while females did not (R2= 0.006, p=0.746). n=21 male BMC and 20 female BMC.

Overall, with the exception of 2 male and 2 female populations, all BMC tested increased in size with the addition of TGFβ1 to the CM (Fig. 2B, *p<0.05 vs. CM). No difference in pellet area was observed between male and female BMC (Fig. 2B). The change in pellet area due to addition of TGFβ1 to the CM was calculated by dividing the area of the pellets that received TGFβ1 by the area of the pellets that received CM only, for every BMC donor. The change in pellet area for male BMC ranged from 0.82 to 6.75 (Table 2 and Fig. 2C). Female BMC were in the range of 0.68 to 3.93, except for a 58-year old female that displayed an increase in pellet area of 9.96 ± 0.47 (Table 2 and Fig. 2C). Regression analysis of all data points indicated that neither sex nor age significantly affected the change in pellet area (age: p=0.124, sex: p=0.856). However, when the analysis was performed on male and female data separately, a significant decrease in the change in pellet area with increasing donor age was found in BMC obtained from males (Fig. 2C, R2=0.253, *p=0.02), but not from females (Fig. 2C, R2= 0.006, p=0.746).

Table 2.

Data for change in pellet area and for Bern score and GAG content of pellets cultured in CM+TGFβ1 for each BMC population.

| Age | Change in pellet area | Bern Score | GAG content/pellet (μg) | Age | Change in pellet area | Bern Score | GAG content/pellet (μg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MALE | 16 | 2.04±0.37 | 6.3±0.9 | N/D | FEMALE | 20 | 1.22±0.08 | 3±2 | 0.31±0.10 |

| 18 | 2.19±0.13 | 7.3±0.7 | 46.74 | 22 | 2.85±0.44 | 7±1 | 33.95±0.56 | ||

| 19 | 6.75±0.14 | 7±0 | 27.23±4.63 | 31 | 1.55±0.27 | 3.3±0.9 | 15.91±0.26 | ||

| 22 | 3.62±0.05 | 9±0 | 28.78±0.46 | 33 | 1.91±0.07 | 8±1 | 15.7±1.50 | ||

| 22 | 3.50±0.31 | 4.5±0.5 | 24.21±1.55 | 38 | 1.53±0.12 | 3.3±0.7 | 27.13±0.86 | ||

| 23 | 1.84±0.19 | 8.5±0.5 | 13.13±0.63 | 40 | 1.50±0.03 | 4±0 | 1.41±0.06 | ||

| 24 | 2.65±0.69 | 7±1 | 9.47±0.35 | 49 | 2.62±0.07 | 6±0 | 26.37±1.25 | ||

| 25 | 6.12±0.31 | 9±0 | 25.30±1.66 | 50 | 1.81±0.52 | 2.3±0.9 | 0.91±0.11 | ||

| 28 | 2.90±0.20 | 8±0 | 48.54±5.42 | 51 | 1.45±0.15 | 4.7±0.3 | 34.3±0.38 | ||

| 28 | 4.00±0.08 | 7.7±0.7 | 46.14±9.38 | 58 | 9.96±0.47 | 8±0 | 19.43±3.37 | ||

| 28 | 1.10±0.08 | 2.5±0.5 | N/D | 59 | 0.68±0.02 | 4.5±0.5 | 2.05±0.39 | ||

| 32 | 0.82±0.19 | 4.5±0.5 | 14.64±1.10 | 62 | 1.39±0.04 | 2±0 | 4.73±1.18 | ||

| 33 | 3.87±0.12 | 4.7±0.3 | 19.76±0.46 | 63 | 2.24±0.01 | 7.7±0.3 | 54.86±2.80 | ||

| 34 | 2.44±0.08 | 5±0.6 | 22.63±5.02 | 66 | 3.93±0.08 | 7.7±0.7 | 10.7 | ||

| 48 | 1.92±0.18 | 6±0 | 33.34±2.69 | 66 | 0.83±0.09 | 4.3±0.3 | 2.29±0.20 | ||

| 53 | 2.90±0.15 | 7.7±0.3 | 25.67±3.10 | 68 | 1.38±0.05 | 3±0 | 0.58±0.07 | ||

| 59 | 1.55±0.07 | 4.5±0.5 | 1.69±0.06 | 68 | 2.89±0.18 | 4.3±0.3 | 16.07±7.78 | ||

| 70 | 0.86±0.05 | 3±0 | 13.36±1.41 | 70 | 1.73±0.14 | 2.5±0.5 | 1.89±0.25 | ||

| 80 | 1.20±0.05 | 2.3±0.3 | 1.67±0.14 | 72 | 1.75±0.02 | 6±0.6 | 0.17±0.14 | ||

| 81 | 1.31±0.07 | 2±1 | N/D | 77 | 1.72±0.19 | 5±0 | 30.04±1.08 | ||

| 82 | 1.62±0.27 | 5.3±0.7 | 10.89±2.83 | ||||||

| Mean | 39.3 | 2.63 | 5.8 | 22.96 | Mean | 53.1 | 2.25 | 4.8 | 14.94 |

| SEM | 4.9 | 0.35 | 0.5 | 3.35 | SEM | 3.84 | 0.44 | 0.4 | 3.44 |

All data are reported as the mean ± SEM.

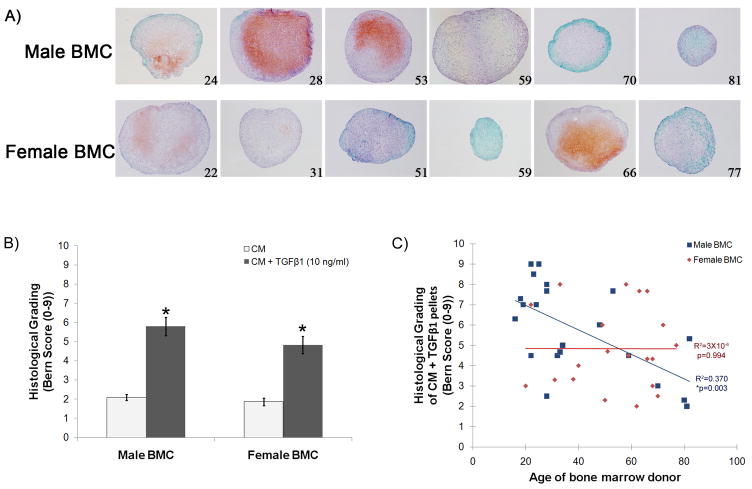

Chondrogenesis

Toluidine Blue staining of chondrogenic pellets provided information on the extent of matrix formation and presence of sulfated polysaccharides. Addition of TGFβ1 to the CM increased chondroid appearance in all populations tested when compared to those in CM only (Fig. 3). However, cells with lacunae, indicative of chondrocyte-like morphology, were more numerous in younger (<30 years old) males than in elderly (>70 years old) males (Fig. 3, arrows). A similar result of more chondrocyte-like cells in pellets containing BMC from younger donors was also seen in the female populations tested (Fig. 3, <30 years old compared to >70 years old). Although some pellets containing BMC from elderly females displayed chondrocyte-like cells and matrix formation, it was not throughout the entire pellet, such as seen in the younger females.

Figure 3. Toluidine blue staining of BMC pellets after 21 days of culture.

Representative images of Toluidine blue staining in pellets containing male or female BMC <30 years old and >70 years old cultured in CM (top row) or CM + TGFβ1 (bottom row). A greater number of chondrocyte-like cells (arrows) were present in younger males than elderly males. The chondrocyte-like cells could be found in elderly females, but they did not span the entire pellet.

Safranin O-Fast Green staining was also investigated as a marker of chondrogenic differentiation. Representative images of male and female BMC pellets cultured in CM supplemented with TGFβ1 are shown in Figure 4A (numbers in lower right hand corner of image indicate the age of the donor). A reduction in the amount of Safranin O-Fast Green staining was observed with increasing donor age in pellets containing male BMC, while pellets containing female BMC did not show a decrease with age. To systematically compare all BMC populations tested for chondrogenesis, histological grading was performed using the Bern score [27]. The histological grading of Safranin O-Fast Green stained pellets is based on the uniformity and darkness of the staining, the amount of matrix formed, and the morphology of the cells within the pellets. The Bern score ranges from 0–9, with higher scores indicative of greater chondrogenic differentiation. Addition of TGFβ1 to the CM resulted in significantly higher Bern scores for both male and female BMC pellets (Fig. 4B, *p<0.05 vs. CM). No significant difference was observed between the scores obtained with male BMC pellets compared to female BMC pellets (Fig. 4B). The effect of age on chondrogenesis was also evaluated. A decrease in chondrogenesis with increasing donor age was found when all BMC populations were analyzed together (Fig. 4C, R2= 0.170, *p=0.007). When the data was separated by donor sex, the chondrogenesis was found to decrease with increasing donor age in male BMC (Fig. 4C, R2=0.370, *p=0.003), but not in female BMC (Fig. 4C, R2= 3×10-6, p=0.994), which displayed a greater degree of variability within all age groups. Measurements obtained from all BMC populations tested in this study can be found in Table 2.

Figure 4. Safranin 0-Fast Green staining of male and female BMC pellets and histological grading.

(A) Representative images of Safranin O-Fast Green staining of pellets containing male or female BMC of increasing donor age that were cultured in CM + TGFβ1 for 21 days. (B) Histological grading of male and female BMC pellets cultured in CM or CM + TGFβ1 using the Bern score. *p<0.05 compared to CM. (C) Bern score for all populations tested. Male BMC showed a declining Bern score with increasing donor age (R2= 0.370, *p=0.003), while females did not (R2= 3×10−6, p=0.994). n=21 male BMC and 20 female BMC.

Quantification of GAG content per pellet provided a quantitative measure of chondrogenic potential (Table 2, Fig. 5). Analysis of all data points revealed that the age of the bone marrow donor had a significant effect on GAG content (Fig. 5, R2= 0.150, *p=0.016). When this effect of donor age on GAG content was analyzed on data acquired from male BMC and female BMC separately, it was determined that an increase in age significantly decreased GAG content in male BMC (Fig. 5, R2= 0.304, *p=0.018), but not in female BMC (Fig. 5, R2= 0.010, p=0.678).

Figure 5. GAG quantification of male and female BMC pellets cultured in CM + TGFβ1 for 21 days.

GAG content per pellet (μg) for all populations tested. Male BMC showed a declining GAG content with increasing donor age (R2= 0.304, *p=0.018), while females did not (R2= 0.010, p=0.678). n=18 male BMC and 20 female BMC.

Discussion

BMC isolated from bone marrow obtained from the distal femur during orthopaedic surgery are similar to the BMC that would be typically accessed during microfracture, a commonly performed cartilage repair procedure. This study showed that femoral BMC can be isolated and expanded from both men and women, regardless of age. However, their degree of in vitro chondroid differentiation following stimulation with TGFβ1 varied by sex. Histological and biochemical analysis indicated an age-related decline in chondroid differentiation with TGFβ1 stimulation in males, but not in females.

Reports on the feasibility of BMC isolation and whether the cell yield is associated with the sex and/or age of the donor are at times conflicting. While some studies have reported a decrease in BMC yield with increasing age [21, 23], others have not found such a relationship [10, 11, 13, 26]. In the present study, BMC were isolated from all samples obtained and the cell yield was similar for all samples, regardless of sex and age. This indicates that it is feasible to isolate femoral BMC for articular cartilage repair in both men and women, regardless of age.

The ability of femoral BMC to proliferate for 8 passages suggests that they have the potential to be expanded for autogenous applications. A decline in proliferation with age was not seen in our study. The results suggest that BMC obtained from the femur of older patients also have the capacity to be expanded for articular cartilage repair and this is consistent with a recent study on femoral BMC isolated from OA patients [13]. Our results are also in accordance with those published on fibrous synovium-, adipose synovium-, and subcutaneous fat-derived mesenchymal cells, which did not show a change in proliferation between young and elderly donors [29].

The increase in pellet area as a result of TGFβ1 stimulation was the first indication that femoral BMC can respond to a chondrogenic stimulus. By area measurement, it was determined that pellets containing cells from older males did not show the same increase in size with addition of TGFβ1 to the CM, as younger male BMC pellets. The increase in pellet area with TGFβ1 stimulation was not affected by donor age in female BMC populations. Positive Safranin O-Fast Green staining suggests extracellular matrix (ECM) development and is a strong indicator of chondrogenesis in vitro. None of the BMC tested displayed positive Safranin O staining when cultured as pellets in CM only, consistent with studies showing the need for TGFβ for BMC chondrogenesis [7–10, 15]. Upon addition of TGFβ1 to the CM, many populations displayed varying intensities of positive Safranin O stain. By combining the Safranin O-Fast Green staining with the Bern score, we were able to systematically compare all the BMC populations tested in this study, and better define the variability seen. This allowed us to determine that male BMC showed a decreased chondrogenic differentiation with increasing donor age, while female BMC showed a similar mean for all age groups. Quantitative measurement of GAG content in pellets further confirmed that a decreased ability to undergo chondrogenesis with increasing age was found to occur in male BMC, but not in female BMC. These results suggest that male BMC may have a diminished responsiveness to TGFβ1 as age increases. A similar finding has been reported in human chondrocytes, where there was a decline in growth factor responsiveness, measured by proliferation rate, with increasing donor age [30]. Another interesting finding is that some populations of BMC isolated from older females undergoing surgery for joint replacement stained highly for Safranin O and had high GAG content per pellet, suggesting that female BMC with a high potential for chondrogenesis may be isolated from elderly females, regardless of their disease state. This finding indicates that BMC therapy could potentially be applied in OA.

The effect of age on chondrogenesis has been previously reported with conflicting results [11, 13, 31–34]. While an age-related decline in chondrogenesis has been reported for rat BMC [31], for undifferentiated BMC in the periosteum [32], for BMC isolated from the iliac crest of normal donors [34], and for human chondrocytes [33], BMC obtained from the open femur shaft of OA patients undergoing hip replacement were found to be independent of age [13]. In comparing our results to these previous studies, it should be noted that all results, including our own, indicated that BMC stimulated with a chondrogenic factor, such as TGFβ1, displayed some degree of chondrogenesis. Our study was designed to analyze a wide range of ages, with a particular interest in the younger patient population, since it has been reported that there is an age threshold between 30 and 40 years of age where the success of microfracture decreases [6]. For this reason, the current study contains many BMC from donors under the age of 40, in addition to BMC from older males, and this allowed us to better determine the effect of age on chondrogenesis. As well, separating the data by the sex of the donor, using the Bern histological grading system, and a quantitative measure such as GAG content, provided a more stringent comparison between the populations tested. This permitted the identification of sex- and age-related differences in the chondrogenesis of femoral BMC when stimulated with TGFβ1.

A variety of growth factors have been reported to induce chondrogenesis in BMC. Members from the TGFβ family have been used extensively, with early reports employing TGFβ1 [8, 10] or TGFβ3 [9, 15] in addition to dexamethasone to promote chondrogenesis in BMC. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) have also been used either individually or in combination to induce chondrogenesis in BMC [35–39]. All have induced some degree of chondroid differentiation, although not necessarily to the same extent [36, 38]. The current study has focused on the response of male and female BMC of various ages to TGFβ1. Age- and sex-related differences in the chondrogenesis of BMC stimulated with other proven growth factors may lead to different outcomes, and is an interesting area to investigate in future studies.

In the case of BMC-based therapies that require expansion ex vivo, it will be important to promote the differentiation potential of all populations, including those with lower observed chondrogenesis to standard chondrogenic stimuli, such as TGFβ1. A potential approach to overcome the decreased differentiation ability of certain BMC populations is the addition of growth factors during cell expansion. This has previously been shown with chondrocytes and BMC [33, 40, 41]. Addition of FGF-2 to the culture medium of human trabecular bone mesenchymal stromal cells from elderly patients led to better osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation potential, yet it did not consistently improve chondrogenesis in all populations tested [40]. Barbero et al. also observed that expansion of chondrocytes with a combination of TGFβ1, FGF-2 and platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) improved the chondrogenic ability of chondrocytes from younger donors, but not donors over the age of 40 [33]. Further studies with similar or different combinations of growth factors are thus warranted to help improve the chondrogenesis of cells with lower differentiation potential.

Overall, this study demonstrated that femoral BMC obtained during orthopaedic surgery are a promising cell source for articular cartilage repair. It indicated that there exists an age-related loss in the chondrogenic potential of male femoral BMC, but not in female femoral BMC. The pellet culture system used in this study is a controlled environment, where TGFβ1 was the main chondrogenic factor. This suggests that with increasing age, the ability of male BMC to respond to TGFβ1 may be impaired. Finding ways to stimulate cartilage repair in older males may require bypassing the TGFβ1 pathway by using other proven chondrogenic growth factors. As well, within the same age group, there were populations that did not undergo chondrogenesis to the same extent. This variability between individuals may explain the different clinical outcomes seen with the microfracture technique. Our findings thus justify further studies on the effect of cell sex and age on chondrogenesis and on the identification of the underlying mechanisms responsible for the differences seen in the BMC that are low-TGFβ1 responders versus the BMC that are high-TGFβ1 responders. Understanding the mechanisms for these observed differences will contribute to improved clinical use of autologous human BMC for articular cartilage repair, and may lead to the development of customized age- or sex-based treatments to delay or prevent the onset of OA.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs. Tarkin, Gruen, and Yates for providing human bone marrow reamings, and Drs. Bear and Seshadri for their help in acquiring the samples. The authors would also like to thank Elise Pringle and Kimberlee Rankin for histological processing. Funding for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health (1 RO1 AR051963) to CRC and by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Arthritis Foundation to KAP.

Funding for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health (1 RO1 AR051963) to CRC and by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Arthritis Foundation to KAP.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brittberg M. Autologous chondrocyte implantation--technique and long-term follow-up. Injury. 2008;39 (Suppl 1):S40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gudas R, Stankevicius E, Monastyreckiene E, Pranys D, Kalesinskas RJ. Osteochondral autologous transplantation versus microfracture for the treatment of articular cartilage defects in the knee joint in athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:834–842. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mithoefer K, McAdams T, Williams RJ, Kreuz PC, Mandelbaum BR. Clinical Efficacy of the Microfracture Technique for Articular Cartilage Repair in the Knee: An Evidence-Based Systematic Analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2009 doi: 10.1177/0363546508328414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bae DK, Yoon KH, Song SJ. Cartilage healing after microfracture in osteoarthritic knees. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreuz PC, Erggelet C, Steinwachs MR, Krause SJ, Lahm A, Niemeyer P, et al. Is microfracture of chondral defects in the knee associated with different results in patients aged 40 years or younger? Arthroscopy. 2006;22:1180–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barry F, Boynton RE, Liu B, Murphy JM. Chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow: differentiation-dependent gene expression of matrix components. Exp Cell Res. 2001;268:189–200. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnstone B, Hering TM, Caplan AI, Goldberg VM, Yoo JU. In vitro chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Exp Cell Res. 1998;238:265–272. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackay AM, Beck SC, Murphy JM, Barry FP, Chichester CO, Pittenger MF. Chondrogenic differentiation of cultured human mesenchymal stem cells from marrow. Tissue Eng. 1998;4:415–428. doi: 10.1089/ten.1998.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoo JU, Barthel TS, Nishimura K, Solchaga L, Caplan AI, Goldberg VM, et al. The chondrogenic potential of human bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1745–1757. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199812000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy JM, Dixon K, Beck S, Fabian D, Feldman A, Barry F. Reduced chondrogenic and adipogenic activity of mesenchymal stem cells from patients with advanced osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:704–713. doi: 10.1002/art.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pagnotto MR, Wang Z, Karpie JC, Ferretti M, Xiao X, Chu CR. Adeno-associated viral gene transfer of transforming growth factor-beta1 to human mesenchymal stem cells improves cartilage repair. Gene Ther. 2007;14:804–813. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scharstuhl A, Schewe B, Benz K, Gaissmaier C, Buhring HJ, Stoop R. Chondrogenic potential of human adult mesenchymal stem cells is independent of age or osteoarthritis etiology. Stem Cells. 2007;25:3244–3251. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakitani S, Goto T, Pineda SJ, Young RG, Mansour JM, Caplan AI, et al. Mesenchymal cell-based repair of large, full-thickness defects of articular cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:579–592. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199404000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tosi LL, Boyan BD, Boskey AL. Does sex matter in musculoskeletal health? A workshop report. Orthop Clin North Am. 2006;37:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corsi KA, Pollett JB, Phillippi JA, Usas A, Li G, Huard J. Osteogenic potential of postnatal skeletal muscle-derived stem cells is influenced by donor sex. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1592–1602. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deasy BM, Lu A, Tebbets JC, Feduska JM, Schugar RC, Pollett JB, et al. A role for cell sex in stem cell-mediated skeletal muscle regeneration: female cells have higher muscle regeneration efficiency. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:73–86. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto T, Kubo S, Meszaros LB, Corsi KA, Cooper GM, Li G, et al. The influence of sex on the chondrogenic potential of muscle-derived stem cells: implications for cartilage regeneration and repair. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3809–3819. doi: 10.1002/art.24125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aksu AE, Rubin JP, Dudas JR, Marra KG. Role of gender and anatomical region on induction of osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;60:306–322. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3180621ff0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Ippolito G, Schiller PC, Ricordi C, Roos BA, Howard GA. Age-related osteogenic potential of mesenchymal stromal stem cells from human vertebral bone marrow. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1115–1122. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.7.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Majors AK, Boehm CA, Nitto H, Midura RJ, Muschler GF. Characterization of human bone marrow stromal cells with respect to osteoblastic differentiation. J Orthop Res. 1997;15:546–557. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muschler GF, Nitto H, Boehm CA, Easley KA. Age- and gender-related changes in the cellularity of human bone marrow and the prevalence of osteoblastic progenitors. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:117–125. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(00)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Justesen J, Stenderup K, Eriksen EF, Kassem M. Maintenance of osteoblastic and adipocytic differentiation potential with age and osteoporosis in human marrow stromal cell cultures. Calcif Tissue Int. 2002;71:36–44. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-2059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stenderup K, Rosada C, Justesen J, Al-Soubky T, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Kassem M. Aged human bone marrow stromal cells maintaining bone forming capacity in vivo evaluated using an improved method of visualization. Biogerontology. 2004;5:107–118. doi: 10.1023/B:BGEN.0000025074.88476.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oreffo RO, Bennett A, Carr AJ, Triffitt JT. Patients with primary osteoarthritis show no change with ageing in the number of osteogenic precursors. Scand J Rheumatol. 1998;27:415–424. doi: 10.1080/030097498442235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grogan SP, Barbero A, Winkelmann V, Rieser F, Fitzsimmons JS, O’Driscoll S, et al. Visual histological grading system for the evaluation of in vitro-generated neocartilage. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2141–2149. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farndale RW, Buttle DJ, Barrett AJ. Improved quantitation and discrimination of sulphated glycosaminoglycans by use of dimethylmethylene blue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;883:173–177. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(86)90306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mochizuki T, Muneta T, Sakaguchi Y, Nimura A, Yokoyama A, Koga H, et al. Higher chondrogenic potential of fibrous synovium- and adipose synovium-derived cells compared with subcutaneous fat-derived cells: distinguishing properties of mesenchymal stem cells in humans. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:843–853. doi: 10.1002/art.21651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guerne PA, Blanco F, Kaelin A, Desgeorges A, Lotz M. Growth factor responsiveness of human articular chondrocytes in aging and development. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:960–968. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng H, Martin JA, Duwayri Y, Falcon G, Buckwalter JA. Impact of aging on rat bone marrow-derived stem cell chondrogenesis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:136–148. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Driscoll SW, Saris DB, Ito Y, Fitzimmons JS. The chondrogenic potential of periosteum decreases with age. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:95–103. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(00)00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barbero A, Grogan S, Schafer D, Heberer M, Mainil-Varlet P, Martin I. Age related changes in human articular chondrocyte yield, proliferation and post-expansion chondrogenic capacity. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stolzing A, Jones E, McGonagle D, Scutt A. Age-related changes in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells: consequences for cell therapies. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;129:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Indrawattana N, Chen G, Tadokoro M, Shann LH, Ohgushi H, Tateishi T, et al. Growth factor combination for chondrogenic induction from human mesenchymal stem cell. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:914–919. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawamura K, Chu CR, Sobajima S, Robbins PD, Fu FH, Izzo NJ, et al. Adenoviral-mediated transfer of TGF-beta1 but not IGF-1 induces chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in pellet cultures. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:865–872. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sekiya I, Colter DC, Prockop DJ. BMP-6 enhances chondrogenesis in a subpopulation of human marrow stromal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:411–418. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sekiya I, Larson BL, Vuoristo JT, Reger RL, Prockop DJ. Comparison of effect of BMP-2, -4, and -6 on in vitro cartilage formation of human adult stem cells from bone marrow stroma. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;320:269–276. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-1075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sekiya I, Vuoristo JT, Larson BL, Prockop DJ. In vitro cartilage formation by human adult stem cells from bone marrow stroma defines the sequence of cellular and molecular events during chondrogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4397–4402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052716199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coipeau P, Rosset P, Langonne A, Gaillard J, Delorme B, Rico A, et al. Impaired differentiation potential of human trabecular bone mesenchymal stromal cells from elderly patients. Cytotherapy. 2009;11:584–594. doi: 10.1080/14653240903079385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jakob M, Demarteau O, Schafer D, Hintermann B, Dick W, Heberer M, et al. Specific growth factors during the expansion and redifferentiation of adult human articular chondrocytes enhance chondrogenesis and cartilaginous tissue formation in vitro. J Cell Biochem. 2001;81:368–377. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(20010501)81:2<368::aid-jcb1051>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]