Abstract

Problem

Retaining physicians in remote settings can be challenging owing to the heavy workload and harsh environmental conditions and to the lack of opportunities for professional development. In Norway, poor physician distribution between urban and rural areas has been persistent, particularly in the north, where in 1997 a total of 28% of the primary care physician positions were vacant.

Approach

Several corrective measures have been tried over the years. One was the establishment of a medical school in the northern city of Tromsø, which proved effective but did not avert new crises. A 1998 survey among primary care physicians signalled the need for new interventions conducive to professional development in rural areas. The existing medical internship and in-service training model for general practice were systematically adopted as tools for retaining physicians.

Local setting

In Finnmark – Norway’s northernmost and most sparsely-populated county – medical practice is challenging, especially at the primary care level. In 1997, a 38% shortage of general practitioners (30 positions) threatened primary care safety.

Relevant changes

Almost twice as many medical interns as expected now take their first fully licensed job in the north of Norway. The post-training retention of primary care physicians after 5 years currently stands at 65%.

Lessons learnt

Postgraduate medical training can be conducted in remote areas in a manner that ensures professional development, counteracts professional isolation, and allows trainees and their families to grow roots in rural communities. Rural practice satisfies modern principles of adult learning (problem-based and attached to real-life situations) and offers excellent training conditions.

ملخص

المشكلة

يتسبب استبقاء الأطباء في المواقع البعيدة التحدِّيات بسبب عبء العمل الثقيل والظروف البيئية القاسية وفقدان الفرص للتنمية المهنية. ويستمر في النرويج سوء توزيع الأطباء بين المناطق الحضرية والريفية، ولاسيَّما في الشمال، حيث كان 28% من وظائف الأطباء في الرعاية الصحية الأولية شاغرة عام 1997.

الأسلوب

جرَّب الباحثون إجراءات تصحيحية متعدِّدة على مدى سنوات طويلة. وقد كان أحد هذه الإجراءات تأسيس كلية طب في المدينة الشمالية ترمسو، وقد بدا هذا الإجراء فعَّالاً ولكنه لم يستطع تفادي الأزمات الجديدة. وقد أظهر مسح أجري عام 1998 على أطباء الرعاية الصحية الأولية مدى الحاجة لتداخلات جديدة تؤدِّي لتطوُّر المهنة في هذه المناطق. وقد تم التبنِّي المنهجي للإقامة الداخلية المتوافرة حالياً للأطباء ولنموذج التعليم أثناء الخدمة في الممارسة العامة، باعتبار ذلك من أدوات استبقاء الأطباء.

الموقع المحلي

تعد الممارسة الطبية من التحدِّيات في فينمارك، وهي أقصى المناطق الشمالية في النرويج وأكثرها تبعثراً من حيث السكان، ولاسيما على مستوى الرعاية الصحية الأولية. ففي عام 1997 كان هناك نقص مقداره 38% في الأطباء العامين يتهدَّد سلامة الرعاية الصحية الأولية.

التغيرات ذات الصلة

استلم ضعف العدد المتوقَّع من الأطباء المقيمين أعمالهم بعد حصولهم على الإجازة الكاملة في شمال النرويج . ويصل الاستبقاء التالي للتدريب لأطباء الرعاية الصحية الأولية بعد مرور خمسة سنوات 65% في الوقت الحالي.

الدروس المستفادة

يمكن القيام بالتدريب الطبي بعد التخرُّج (الدراسات العليا) في المناطق النائية بأسلوب يضمن تطوير المهنة ويقاوم انعزال الأطباء، ويسمح للمتدربين ولأسرهم بالتغلغل في جذور المجتمعات الريفية. إن الممارسة الريفية تفي بالمبادئ المعاصرة لتعلم البالغين (مستندة على حل المشكلات وتتصل بأوضاع الحياة الحقيقية) وتقدم ظروفاً تدريبية ممتازة.

Résumé

Problématique

Retenir les médecins dans des endroits reculés peut être difficile compte tenu de la lourde charge de travail, des conditions environnementales rigoureuses et du manque de possibilités d'évolution professionnelle qui les y attendent. En Norvège, on constate la persistance d'une répartition déséquilibrée des médecins entre zones rurales et zones urbaines, notamment dans le Nord, où en 1997, 28 % des postes de médecins de soins de santé primaires étaient vacants.

Démarche

Plusieurs mesures correctives ont été testées au cours des années. L'une d'elles consistait à établir une école de médecine dans la ville septentrionale de Tromsø, mesure qui s'est révélée efficace, mais n'a pas empêché de nouvelles crises. Une enquête réalisée en 1998 chez les médecins de soins de santé primaires, a fait ressortir la nécessité de nouvelles interventions en faveur du développement professionnel dans les zones rurales. L'internat médical existant et le modèle de formation en continu dont bénéficient les généralistes ont été systématiquement adoptés comme outils pour retenir les médecins.

Contexte local

Au Finnmark - conté norvégien le plus septentrional et le plus faiblement peuplé- la pratique de la médecine représente un défi, en particulier pour les soins de santé primaire. En 1997, une pénurie de généralistes atteignant 38 % (30 postes) a menacé la pérennité des soins de santé primaire.

Modifications pertinentes

On s'attend maintenant à ce que le nombre d'internes en médecine prenant leur premier poste de médecin pleinement autorisé dans le Nord de la Norvège soit multiplié par deux. Au bout de 5 ans, le taux de rétention des médecins de soins de santé primaires formés se situe actuellement à 65 %.

Enseignements tirés

Une formation médicale postdoctorale peut être délivrée dans les zones reculées de manière à assurer le développement professionnel, à remédier à l'isolement professionnel et à permettre aux personnes en formation et à leurs familles à cultiver des racines dans les communautés rurales. La pratique rurale satisfait aux principes modernes de la formation pour adultes (enseignement par résolution de problèmes et proche des situations réelles) et offre d'excellentes conditions de formation.

Resumen

Problema

No es fácil garantizar la permanencia de los médicos en las zonas remotas, debido a la gran carga de trabajo y las duras condiciones ambientales que deben afrontar, así como a la falta de oportunidades de desarrollo profesional. En Noruega, la desigual distribución de los médicos entre las zonas urbanas y las rurales es un problema persistente, sobre todo en el norte del país, donde en 1997 un 28% de los puestos de médico de atención primaria estaban vacantes.

Enfoque

A lo largo de los años se han ensayado varias soluciones posibles. Una de ellas consistió en crear una escuela de medicina en la ciudad septentrional de Tromsø, medida que pese a resultar eficaz no evitó nuevas crisis. Una encuesta realizada en 1998 entre los médicos de atención primaria reveló la necesidad de llevar a cabo nuevas intervenciones de fomento del desarrollo profesional en las zonas rurales. Como medio para fidelizar a los médicos, se adoptó de forma sistemática el modelo que había de formación de residentes y formación en el servicio orientado a la medicina general.

Contexto local

En Finnmark, la región más septentrional y menos poblada de Noruega, el ejercicio de la medicina es una actividad ardua, especialmente en el nivel de atención primaria. En 1997, un déficit de un 38% de médicos generalistas (30 puestos) puso en peligro la atención dispensada en ese nivel.

Cambios destacables

Actualmente el número de residentes que aceptan su primer trabajo como licenciados en el norte de Noruega casi duplica la cifra prevista. La permanencia posformación de los médicos de atención primaria al cabo de cinco años es hoy del 65%.

Enseñanzas extraídas

Es posible implantar en las zonas remotas una formación médica de posgrado que garantice el desarrollo profesional, contrarreste el aislamiento profesional, y permita a los profesionales y a sus familiares echar raíces en las comunidades rurales. La medicina rural satisface los principios modernos de la formación de adultos (basada en problemas y relacionada con situaciones de la vida real) y ofrece excelentes condiciones para la capacitación.

Introduction

The health-care system in Norway – a rich country covering a relatively large area for its population of only 4.8 million – is predominantly public and provides tax-based universal coverage. Its comprehensive primary care is organized at the municipal level. Specialized care is organized at the national level through regional health enterprises directly accountable to the Ministry of Health.

In Norway, the density of physicians and other health professionals is one of the highest in Europe. Health professionals enjoy a high income and good working conditions. Higher education is free for all, but domestic capacity for physician training is insufficient. Hence, the government offers students scholarships and loans to study abroad.

Norway has a strong policy for rural development and grants citizens in both rural and urban areas the same legal rights to good health services. However, providing sufficient qualified health professionals, particularly physicians, has been a major challenge for health service delivery in the northern part of Norway for decades.1

The rural crisis

For five decades Norway has faced a fluctuating shortage of physicians at the national level, mostly driven by an increasing demand for advanced specialized care.2 Since 1984 primary care and the recruitment and retention of health workers have been organized at the municipal level. The small, northern municipalities have neither the funds nor the skills to compete with specialized care in urban municipalities in the south.

In the mid-1990s northern Norway experienced a critical shortage of primary care physicians. In 1997 the percentage of vacant physician positions was 28 on average3 and as high as 37 in some of the smaller municipalities. To mitigate the crisis, municipalities had to engage short-term replacements, most of them flown in from Sweden and Denmark at a considerable cost.

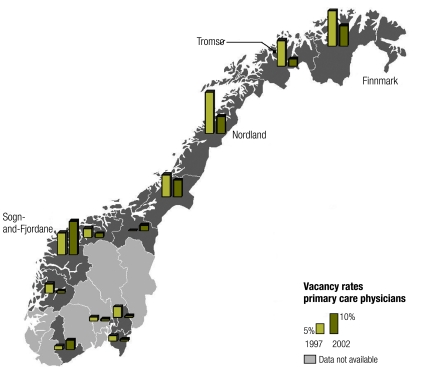

Norway’s uneven distribution of health workers between rural and urban areas is longstanding. As illustrated in Fig. 1, northern Norway and some areas on the west coast have been particularly affected by shortages, while areas in the central eastern portion are well staffed. Several strategies have been implemented to attract health workers to northern Norway and retain them there. The most comprehensive one was the establishment of a medical school in Tromsø, the capital of northern Norway, favouring students from the region and providing rural rotations in the curriculum. The measure has had a large positive effect on the region’s supply of physicians.4

Fig. 1.

Primary care physician vacancies across Norwegian counties, 1997 and 2002

Image produced by national authorities in Norway using a geographical information system and data from: Annual report of Country Medical Officers (1997), National General Practitioner Register (2002).

The crisis in Finnmark

Covering an area larger than Switzerland, Finnmark county has only 73 000 inhabitants, most of whom reside in fishing villages along the coast and in inland settlements dominated by the semi-nomadic indigenous Sami population. Only three municipalities have more than 10 000 inhabitants, two of them hosting a small hospital (with 60 and 100 beds, respectively). The nearest city, Tromsø, in the neighbouring county (Fig. 1), hosts a university hospital and a medical school.

Medical practice in Finnmark is challenging, especially at the primary care level. Long distances and the harsh climate make transporting patients to higher-level facilities very difficult. In remote communities, health workers at the primary care level must often treat conditions normally dealt with in hospitals in other parts of the country.

Finnmark’s health workforce crisis peeked in 1997. In the autumn of that year, 19 (23%) primary care physician posts were vacant, and 12 (15%) others were occupied by physicians on long-term leave. To manage this shortage, the municipalities had to hire foreign substitutes on short-term, very expensive contracts. Furthermore, the substitutes had not been trained for the challenges of practising in the area.

Information gathering

Finnmark was granted the funds by the Ministry of Health to address the crisis. In 1998, a survey was conducted to explore the factors influencing primary care physicians’ decision to remain in or abandon northern Norway.5 Lack of opportunities for professional development were found to be the most common reason for leaving – more common than wage- and workload-related factors. On the other hand, the enjoyable aspects of rural living and working conditions were the most important reasons for staying.

Interventions

The results of the survey prompted new interventions aimed to facilitate sustainable professional development in Finnmark. Efforts centred on finding interventions that could be sustained under the existing training system.

In keeping with Norway’s strong national rural development policy, specialist training programmes in general practice (family medicine) and in public health (community medicine) were designed as decentralized models that could be implemented anywhere in the country.6 These programmes are based on in-service training and group tutorials, in contrast to the traditional didactic models, which are centralized to larger training facilities and rely on one-to-one tutorials. Though this new training model had been effective since 1985, it had not been fully explored as a tool for retention.

Medical internship was another intervention that had not been used to full potential. In Norway, medical graduates must intern for 18 months (including 6 months in general practice) before being fully licensed as physicians. Rural areas have a high proportion of all internships, and interns are their primary source of physician recruitment. However, this recruitment failed during the health worker crises of the 1990s.

The new primary care internship initiative in Finnmark was launched in 1998. Interns were gathered into tutorial groups and encouraged to discuss the challenges to their demanding roles and their potential solutions. The meetings also provided opportunities to overcome professional and social isolation by networking with peers from neighbouring municipalities.7

Interns who agree to take up vacant positions in Finnmark after internship are guided into groups for training in general practice and public health, with all specialist training expenses covered.8 The county medical association also arranges for courses and professional fellowships twice a year. Hence it is possible to fully specialize in general practice and public health largely without leaving Finnmark. Both internship and postgraduate training take place in all the small municipalities in the county, not only in the towns.

Results

The results of the internship project have been reported annually to the Ministry of Health and have recently been more thoroughly evaluated. The training groups in general practice and family medicine and in public health and community medicine were first evaluated in 2003 and again in 2009.

The main results are encouraging: Of the 267 medical graduates who interned in Finnmark from 1999 to 2006, almost twice as many as expected have accepted their first fully licensed job in the region. Of the 53 physicians who completed training in general practice and family medicine or in public health and community medicine in Finnmark from 1995 to 2003, 34 (65%) were still working in the county 5 years later.

To assess the impact of these results, a simple before–and–after analysis of vacancy rates is misleading, since the workforce market for physicians is influenced by several other factors and fluctuates over time. In 1997 the county of Nordland was appointed as a “control group,” but because of a critical physician shortage in 1998, it was allowed to implement some of the same strategies. As seen from Fig. 1, the remote county of Sogn-and-Fjordane, on the west coast, constitutes the best comparison over the same period of time.

During the 1990s, the shortage of physicians received less attention in Sogn-and-Fjordane than in Finnmark. As a result, after interventions were implemented, vacancy rates continued to increase in Sogn-and-Fjordane, whereas in Finnmark they began to drop (Table 1). Nordland also experienced a marked reduction in vacancy rates after implementing similar measures. In 2002 the problem in Sogn-and-Fjordane was seriously addressed using approaches similar to Finnmark’s, and vacancy rates then started to drop.9

Table 1. Primary care physician vacancies in two comparable rural Norwegian counties from 1997 to 2004, as reported by the county medical officers.

| Year | Finnmark | Sogn-and-Fjordane | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | VPa | TP | VPa | ||||||

| No. | No. | % | No. | No. | % | ||||

| 1997 | 81 | 13 | 16.0 | 100 | 12 | 12.0 | |||

| 1998 | 81 | 14 | 17.3 | 99 | 18.5 | 18.7 | |||

| 1999 | 83 | 13 | 15.6 | 99 | 13.5 | 13.6 | |||

| 2000 | 83 | 16 | 19.3 | 99 | 13 | 13.1 | |||

| 2001 | 86 | 16 | 18.8 | 102 | 19 | 18.6 | |||

| 2002 | 86 | 8 | 9.3 | 104 | 17 | 16.3 | |||

| 2003 | 86 | 6 | 6.9 | 104 | 10 | 9.6 | |||

| 2004 | 86 | 7 | 8.1 | 104 | 13 | 12.5 | |||

TP, total positions for primary health physicians in the county; VP, vacant positions for primary health physicians in the county.

a Vacancy figures are for the end of each year.

Discussion

The professional support interventions described were not solely responsible for improved physician retention, which has been hampered over the years by multiple factors, such as labour market flows. However, they have contributed substantially to the improvements noted and should be considered by other countries facing rural health workforce retention challenges. In most countries, postgraduate training is carried out in central areas and physicians are recruited to remote areas as fully trained specialists. By allowing for training in remote areas, the Norwegian model makes it possible for trainees and their families to grow roots in rural communities during the training period.

This training model does not produce “second class” doctors. In fact, rural medical practice poses unique challenges and provides excellent conditions for learning when supported by appropriate tutelage. The training curriculum, which adheres to modern principles of adult learning, is flexible enough to meet the learning need of trainees. Tutorials in rural areas can cover clinical topics of special relevance for rural practice, and tutorial groups also offer an opportunity to create a professional network in the region as a way to counteract professional isolation over ensuing years. The Norwegian model also includes continuous medical education that can be carried out in remote areas (Box 1). It is not a “special offer” for rural and remote areas; it follows the same methods applied throughout Norway and the specialist accreditation is valid everywhere in the country.

Box 1. Summary of main lessons learnt.

Postgraduate medical training can be successfully carried out in remote areas in a manner that ensures professional development and counteracts professional isolation, resulting in improved health workforce retention in rural settings.

By allowing for postgraduate medical training in remote areas, the Norwegian model makes it possible for trainees and their families to grow roots in rural communities during training.

Rural practice satisfies modern principles of adult learning (problem-based training attached to real-life situations) and offers excellent learning conditions for physicians in training.

Transferability of the model

Any country facing a poor distribution of health professionals between rural and urban areas should consider adapting its training systems to rural areas, in the interest of improving rural recruitment and retention.1 According to modern principles of adult learning, training should be problem-based and attached to real-life situations, and rural practice satisfies these conditions while offering excellent learning conditions.

Unfortunately, in many countries postgraduate training is in the hands of conservative professional bodies that favour a centralized approach. In the interests of an improved health-care system, convention should be challenged. This Norwegian example is not unique in countering traditional academicism: under quite different conditions, in southern Africa a large-scale masters programme in public health with participants from different cadres and several countries in the region has successfully been carried out as an in-service distance education model.10 Other recent reviews show that rural health workforce retention can often be improved through innovative, yet often relatively simple, solutions.11

When implementing interventions to improve rural retention and recruitment, the local context must be considered. This is made clear by similar interventions in differing settings that have had varying success.12–15 Nevertheless, although working conditions vary widely around the world, health professionals share common features: they are highly educated and eager to continue their professional development throughout their working lives. Providing the opportunities for them to do so in rural areas, as elsewhere, is crucial for retaining them in remote rural posts.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Dolea C, Braichet JM, Shaw DMP. Health workforce retention in remote and rural areas: call for papers. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:486. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.068494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haugsbø A.Legemangelen i Nord-Norge gjennom tre tiår [Shortage of physicians in Northern Norway over three decades]Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 19881081809–10.Norwegian [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen F, Forsdahl A. Kommunelegetjenesten i Nord-Norge 1995-97. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1999;119:1296–8. [Primary care physicians in Northern Norway 1995-97] Norwegian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magnus JH, Tollan A. Rural doctor recruitment: does medical education in rural districts recruit doctors to rural areas? Med Educ. 1993;27:250–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1993.tb00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsen AG. Hvilke faktorer får leger til å velge seg bort fra Nord-Norge? [Factors influencing physicians to abandon Northern Norway]. Tromsø: University of Tromsø, Institute for Public Health; 1998. Norwegian.

- 6.Westin S, Østensen AI, Lövslett K, Prytz J, Telje J, Telstad W, et al. A group-based training programme for general practitioners: a Norwegian experience. Fam Pract. 1988;5:244–52. doi: 10.1093/fampra/5.4.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Straume K, Shaw DMP. Internship at the ends of the Earth – a way to recruit physicians? Rural Remote Health J. 2010 Forthcoming. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Straume K, Søndenå M, Prydz P. Post-graduate training at the ends of the Earth – a way to retain physicians? Rural Remote Health J. 2010 Forthcoming. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Øgar P. Regular GP scheme in Sogn and Fjordane – success or failure? Annual report of the County Medical Officer of Sogn and Fjordane. County Medical Officer; 2002. Available from: www.helsetilsynet.no [accessed on 16 March 2010]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander L, Igumbor EU, Sanders D. Building capacity without disrupting health services: public health education for Africa through distance learning. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolea C, Stormont L, Shaw DMP, Zurn P, Braichet JM. Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/migration/background_paper.pdf [accessed 16 March 2010]. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Omole OB, Marincowitz G, Ogunbanjo GA. Perceptions of hospital managers regarding the impact of doctors' community service. South Afr Fam Pract. 2005;47:55–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wibulpolprasert S, Pengpaibon P. Integrated strategies to tackle the inequitable distribution of doctors in Thailand: four decades of experience. Hum Resour Health. 2003;1:12. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nestman NA. The retention of physicians in rural areas: the case of Nova Scotia. Kingston: Industrial Relations Centre, Queen's University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavender A, Albán M. Compulsory medical service in Ecuador: the physician’s perspective. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:1937–46. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]