Abstract

Aim:

During adolescence, some individuals with autism engage in severe disruptive behaviors, such as violence, agitation, tantrums, or self-injurious behaviors. We aimed to assess risk factors associated with very acute states and regression in adolescents with autism in an inpatient population.

Method:

Between 2001 and 2005, we reviewed the charts of all adolescents with autism (N=29, mean age=14.8 years, 79% male) hospitalized for severe disruptive behaviors in a psychiatric intensive care unit. We systematically collected data describing socio-demographic characteristics, clinical variables (severity, presence of language, cognitive level), associated organic conditions, etiologic diagnosis of the episode, and treatments.

Results:

All patients exhibited severe autistic symptoms and intellectual disability, and two-thirds had no functional verbal language. Fifteen subjects exhibited epilepsy, including three cases in which epilepsy was unknown before the acute episode. For six (21%) of the subjects, uncontrolled seizures were considered the main cause of the disruptive behaviors. Other suspected risk factors associated with disruptive behavior disorders included adjustment disorder (N=7), lack of adequate therapeutic or educational management (N=6), depression (N=2), catatonia (N=2), and painful comorbid organic conditions (N=3).

Conclusion:

Disruptive behaviors among adolescents with autism may stem from diverse risk factors, including environmental problems, comorbid acute psychiatric conditions, or somatic diseases such as epilepsy. The management of these behavioral changes requires a multidisciplinary functional approach.

Keywords: autism, adolescence, acute behavioral state, regression, intellectual disability

Résumé

Objectif:

À l’adolescence, certains autistes affichent des troubles graves du comportement tels que violence, agitation, colère ou auto-mutilation. Cette étude évalue les facteurs de risque associés aux états aigus et à la régression chez les adolescents autistes hospitalisés.

Méthodologie:

Nous avons étudié, de 2001 à 2005, le dossier d’adolescents souffrant d’autisme (n=29, âge moyen=14,8 ans, 79% de sujets de sexe masculin) hospitalisés pour troubles sévères du comportement dans un service psychiatrique de soins intensifs. Nous avons systématiquement recueilli les informations suivantes: données socio-démographiques des adolescents, variables cliniques (gravité, présence de langage, niveau cognitif), maladies organiques connexes, étiologie de l’épisode aigu et traitements reçus.

Résultats:

Tous les patients présentaient des symptômes autistiques et une déficience intellectuelle; deux tiers d’entre eux n’avaient pas de niveau du langage fonctionnel. Quinze sujets présentaient des symptômes épileptiques, et l’épilepsie n’avait pas été diagnostiquée chez trois de ces sujets avant l’épisode aigu. Les crises incontrôlées étaient considérées comme la cause principale des troubles sévères du comportement chez six sujets. Les autres facteurs de risque étaient notamment le trouble d’ajustement (n=7), le manque de traitement thérapeutique ou éducatif (n=6), la dépression (n=2), la catatonie (n=2) et les maladies physiques comorbides (n=3).

Conclusion:

Les troubles sévères du comportement des adolescents autistes peuvent être dus à divers facteurs de risque: facteurs environnementaux, comorbidités psychiatriques aigues ou maladies somatiques comme l’épilepsie. Ces comportements exigent une approche multidisciplinaire.

Keywords: autisme, adolescence, trouble sévère du comportement, régression, déficience intellectuelle

Introduction

Adolescence is a particularly important period in the course of development. Regarding neuropsychiatric disorders, adolescence is the period of onset for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and catatonia (Cohen et al., 2005). Adolescence is also one of the peak periods of seizure occurrence (Tuchman and Rapin, 2002). In the field of autism, some authors have observed that the onset of puberty is temporally associated with clinical deterioration (Gillberg and Schaumann, 1981; Billstedt et al., 2005). However, most children with autism grow up and become adolescents and then adults, without manifesting major adult psychiatric disorders. Indeed, the core symptoms of autism – deficiencies in social interaction, language delay and communication disabilities, and restricted and stereotyped behavior – tend to show improvement over time (Rutter and Lockyer, 1967; Rutter et al., 1967; Kobayashi and Murata, 1998; Seltzer et al., 2003), and only a few individuals with autism experience severe disruptive disorders during adolescence.

The literature on autism during adolescence and adulthood is sparser than that concerning autism during childhood despite some challenging behaviors that persist throughout adulthood. In a review of studies published before 1996, Nordin and Gillberg (1998) observed that cognitive or behavioral regression occurred in 12 to 22% of adolescents with autism. The largest study of this phenomenon, a survey conducted on 201 young adults with autism born in Japan, indicated that 32% of them showed marked deterioration during adolescence (Kobayashi et al., 1992). More recently, a prospective study conducted on 120 Swedish autistic subjects showed that behavioral and cognitive regression, catatonia, and “adult psychosis” occurred during adolescence in 16%, 12%, and 8% of those studied, respectively (Billstedt et al., 2005). Finally, Mouridsen et al. (2008) showed using a case-control method that adults with autism had a higher frequency of additional treatable psychiatric disorders than controls, in particular psychotic disorders and affective disorders.

Normal intellectual abilities seem to be protective: among individuals with autism, those without intellectual disability experience less deterioration than those with mental disabilities (Venter et al., 1992; Ballaban-Gil et al., 1996). Similarly, among individuals with intellectual disability, those with autism experience more deterioration than those without autism. From an epidemiological sample of subjects with intellectual disabilities in Ontario [Canada], Bradley and Bolton (2006) compared the prevalence of episodic psychiatric disorders in adolescents with intellectual disability with (N=36) and without (N=36) autism. They found that autism was significantly associated with the total number of episodes and with psychotropic prescriptions. At least one episode of psychiatric illness occurred in the 17 individuals with autism. These episodic illnesses were depressive disorders (N=8), bipolar disorders (N=2), adjustment disorders (N=3), and persistent and unclassifiable disorders (N=4) (Bradley and Bolton, 2006).

In summary, severe behavioral changes and mental health problems in adolescents with autism are poorly investigated and inadequately understood. In particular, no empirical guidelines are available regarding etiology and treatment, as there are very few studies concerning inpatient treatment of subjects with autism (Shattuck et al., 2007) and, to our knowledge, none focusing on adolescence. The present study aimed to screen all patients with autism hospitalized in a psychiatric intensive care unit for severe behavioral disturbances occurring during adolescence. Some guidelines for diagnosis and treatment are suggested based on this clinical experience.

Methods

Participants

By reviewing patient charts and staff reports, we systematically looked for all adolescents with autism who were hospitalized for an acute episode of disruptive behavior between January 2000 and December 2005 at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, a University teaching hospital that treats 30–40% of all child and adolescent psychiatry inpatients in the Paris area [10 million people]. It is the only hospital that has an adolescent Psychiatric Intensive Care Unit treating life-threatening treatment refusal (Jaunay et al., 2006), catatonic syndrome (Cohen et al., 2005; Cornic et al., 2009), severe mood disorders (Taieb et al., 2002), and severe behavioral regression. During the study period, 41 out of nearly 420 adolescent inpatients were hospitalized with a discharge diagnosis of autism, Asperger’s syndrome, or pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) not otherwise specified. Two experienced child and adolescent psychiatrists from the department (DP and CA) reviewed the charts and selected the cases (N=29) meeting the following criteria: (a) ICD-10 diagnosis of childhood autism confirmed by the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) (Shopler et al., 1980), which is used routinely in the department; (b) aged between 12 and 17 years old at the time of admission; (c) the main reason for admission was disruptive behavior or cognitive regression. No a priori exclusion criteria were used. The ICD-10 nosography is a criteria-based classification. For autism, the criteria are very similar to those used in the DSM-IV. It defines autism with three symptomatic domains (qualitative impairment in social interaction, qualitative abnormalities in communication, and restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities) and one developmental criterion (abnormal or impaired development is evident before the age of 3 years). We strictly checked for the presence of the required criteria, especially the age criterion. For example, one case was excluded because of his developmental history, which led to a diagnosis of childhood disintegrative disorder rather than autism.

Procedure and variables

We retrospectively reviewed charts, including clinician and nurse notes, from the hospitalization period. All information pertaining to the identity of the subjects was removed. Two co-authors (DP and CA) independently extracted the relevant data from the original selected reports and reviews. Contradictory data between the two co-authors were checked for improper extraction or consensus decision.

Selected data included socio-demographic data: age, gender, socio-economic status of the family based on income and parental work activity [classified into three groups: low, middle, and high], and composition of the family at the time of admission [number of siblings and marital status of the parents]. Special focus was placed on the type of care provided to the patients at the time of admission. The individuals were classified into three groups: those who received no institutional care or education [i.e., stayed at home all day], those who received care and education in non-specific institutions [mainly institutions dedicated to all types of intellectual disability], and those who received care and education in institutions dedicated to PDD.

Recorded data also included a detailed medical history that was based on past personal and family psychiatric history recorded at intake with a semi-structured interview (Taieb et al., 2002). A particular emphasis was placed on associated pathologies, such as epilepsy, genetic disorders, and other chronic illnesses associated with autism.

Due to the difficulties involved in testing individuals who exhibit such problematic behaviors, subjects were identified as having intellectual disability according to the definition of the American Association on Mental Retardation. The estimates of cognitive ability were based on performance before the onset of the acute state that required hospitalization. Information was obtained from case records and interviews with parents and caregivers. Individuals were classified into five groups: profound, severe, moderate, and mild intellectual disability, and borderline-normal cognitive ability. For the same reasons, a similar method was used to estimate the level of expressive language before the onset of the acute state. The individuals were classified into three groups: those with no expressive language at all, those with only a few words or with very impaired expressive language [a maximum of 15 words was chosen arbitrarily], and those with greater abilities in this domain.

Other clinical variables at admission included CARS scores and the symptoms listed for referral. For descriptive purposes, pathological behaviors were classified into eight groups: aggression or violence toward others, self-injurious behaviors, severe stereotypies, hyperactivity, tantrums, panic attacks, catatonia, and instinctual disorders [severe disturbance concerning sleep, alimentation, sexuality, or urinary/fecal control].

Other variables were collected regarding the hospitalization process. The team consensus best-estimate diagnostic method, which is usually used to ascertain clinical diagnoses or data, was used to define the etiology of the acute state retained at discharge (Klein et al., 1994). The team included the two co-authors that extracted the data, two senior psychiatrists with a large amount of experience in inpatient care (DC, AC), and a neurologist with expertise in epilepsy (IAG). The etiology was the primary explanation retained for the behavioral regression. Postulated etiologies were based on all available information, including direct interviews, family history data, and treatment records (Klein et al., 1994). Each case received only one major postulated etiology, whereas several contributing factors were present in some cases. Postulated organic etiologies were confirmed if the specific treatment for that etiology positively affected the disruptive behaviors.

Finally, several types of data regarding treatment were also collected, including the duration of the hospitalization, the type and number of prescribed medications, adverse effects of medications, and paraclinical investigations (i.e., EEG and neuroimaging). The effectiveness of the hospitalization was measured with the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (C-GAS), which is systematically used in the department at admission and discharge.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R software, version 2.7 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Univariate analyses were used to examine the importance of various variables in the explanation of short-term outcomes upon discharge, including the change in GAF score [¢GAF = GAF at discharge – GAF at admission] and duration of hospitalization. We tested the following explicative variables: age, sex, socio-economic status, family ethnic origin, episode causes [no treatment/maladaptive/organic/psychiatric], level of intellectual disability (ID), history of an organic developmental disorder, and CARS and GAF scores at intake. For quantitative explicative variables, Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to estimate the strength of the linear association with the ¢GAS and the duration of hospitalization. ANOVAs were performed with qualitative explicative variables. The assumption of homogeneity of variances was checked by Levene’s test, and the assumption of normality was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. In the case of the rejection of the hypothesis of equality of means, Tukey’s post-hoc tests were applied.

Results

Socio-demographic, personal history, and clinical characteristics at admission

Twenty-nine subjects were included (23 males, 6 females). The male-female ratio was 3.8/1. The mean age was 14.8 (±1.3) years. In total, 15 of the subjects’ parents lived as couples (52%), whereas 14 of the subjects’ parents were single without the presence of a stepfather or stepmother in the home (48%). The majority of patients (N=18, 62%) were from immigrant families. Socio-economic status was low for 12 individuals (41%) and middle or high for 17 individuals (59%). The mean number of siblings was three.

All subjects had severe autistic syndrome (CARS score: mean (±SD) = 41.9 (±3.2)) associated with intellectual disability: mild ID in 6 cases (21%), moderate ID in 8 cases (28%), severe ID in 14 cases (48%), and profound ID in 1 case (3%). The majority had poor language abilities: there was no language in 9 cases (31%), a few words in 11 cases (38%), and functional language in 9 cases (31%). All of the patients with a comorbid organic condition (N=15) also had seizures. Twelve patients had essential epilepsy, including three who were diagnosed during hospitalization. One patient had fragile X syndrome, one had tuberous sclerosis, and one had FG syndrome (a multiple congenital anomaly/intellectual disability syndrome). Three patients had syndromic epilepsy [West syndrome, continuous spikes and waves during slow sleep (CSWSS), Lennox-Gastaut syndrome]. Prior to admission to the hospital, only five patients (17.2%) received care in a specialized institution for PDD individuals. Eleven patients (38%) received institutional care in nonspecific psychiatric settings or in special programs for youths with intellectual disability. Thirteen patients (44.8%) received no specialized or institutional care and stayed at home. Furthermore, 16 patients (55.2%) had received no care during more than one year of their life.

Reasons for referral are listed in Table 1. The mean number of disruptive symptoms was 2.6. Only three subjects had one symptom. The mean GAS score at the time of admission was 19.2 (±7.9). The mean number of psychotropic drugs prior to admission was 1.4 [range: no medication to 5 compounds].

Table 1.

Disruptive symptoms and reasons for referral

| Disruptive symptom | N |

|---|---|

| Hetero-aggressivity | 19 |

| Hyperactivity | 17 |

| Instinctual disorder (severe disturbance in sleep, alimentation, urinary/fecal control, or sexuality) | 15 |

| Stereotypies | 7 |

| Self-Injurious Behaviors | 6 |

| Tantrums | 5 |

| Panic attacks | 5 |

| Catatonia | 2 |

Paraclinical examination, retained diagnosis, and inpatient care

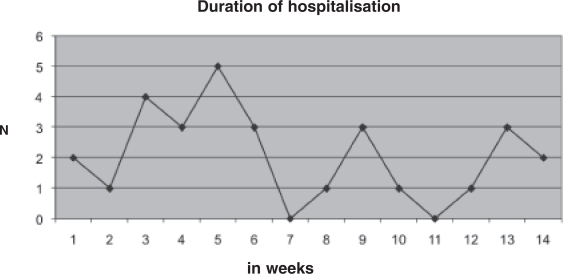

The mean duration of hospitalization was 44 (±28) days. The distribution of the duration was not unimodal; three peaks could be distinguished (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Duration of hospitalization (in weeks) for acute behavioral states in adolescents with autism.

The mean duration of hospitalization was six weeks and was similar to the median. This duration did not show a normal distribution, and three peaks could be distinguished. Adolescents with severe intellectual disability had significantly longer inpatient stays.

Paraclinical examinations, such as EEG and neuroimaging, were prescribed in 25 cases (87%) and 17 cases (59%), respectively. In many cases, however, behavioral disturbances prevented technicians from performing these examinations or made the results unusable. Nineteen patients underwent an EEG (76%) and 11 patients underwent neuroimaging (65%).

The retained etiologies are listed in Table 2. For each patient, only the principal etiology was retained. In summary, the acute state was caused by environmental causes in 13 patients (45%), an organic cause in 9 patients (31%), and a psychiatric cause in 4 patients (14%). In three cases, despite being sent to the inpatient unit from specific institutions dedicated to PDD, no apparent cause was found for the acute episode. For these three patients, we can hypothesize that they presented with a psychiatric diagnosis that was misdiagnosed due to their absence of language.

Table 2.

Best retained etiology for the acute state

| Diagnosis | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Environmental causes | |

| Lack of treatment | 7 (24) |

| Adjustment disorder | 6 (21) |

| Organic causes | |

| Seizures | 6 (21) |

| Other organic condition | 3 (10) |

| Psychiatric causes | |

| Catatonia | 2 (7) |

| Major depressive episode | 1 (3) |

| Bipolar disorder | 1 (3) |

| Unknown | 3 (10) |

Regarding psychiatric disorders, the diagnoses were made according to the ICD-10 criteria. In the current series, we listed four psychiatric comorbid conditions with acute states in autism (catatonia, major depression, bipolar disorder, and adjustment disorder). Although adjustment disorder is a psychiatric diagnosis according to the ICD-10 and DSM-IV, we considered it as an environmental cause that should be differentiated from the other specific psychiatric disorders found. As explained in the methods section, we did not consider adjustment problems associated with a change of routine in patients with autism. An adjustment disorder was diagnosed when a major modification or a breakdown of the patient’s environment was the explanation for the disruptive symptoms. It included severe maltreatment for one patient, the recent death of one patient’s father, the psychiatric hospitalization of two patients’ mothers, the hospitalization for cancer of one patient’s mother, and an unanticipated change of institution for one patient.

A lack of specific treatment was considered as the cause when both (a) a lack of appropriate care (including no care at all) was considered responsible for the acute state and (b) the inpatient setting was sufficient to reduce behavioral symptoms. Finally, we also observed organic conditions. The acute state was caused by uncontrolled seizures in six patients, and antiepileptic medications led to significant improvement. For three of them, this marked their first diagnosis of seizures. Other non-neurological organic causes were observed in three cases, including Helicobacter pylori gastritis, tooth decay, and urinary tract infection. In these three cases, the specific treatment of the condition led to a significant decrease in the disruptive behaviors.

The mean number of psychiatric medications at discharge was 1.7, and 27 patients (93%) were prescribed an antipsychotic. Most of them took one antipsychotic (N=22), and the remaining five took two. Fifteen patients received an anti-epileptic drug, and most of these patients had only one antiepileptic medication (N=8). Two patients took more than two drugs but had syndromic epilepsy [Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or CSWSS]. Short-term adverse effects of prescription medications were observed in 2/3 of the patients. They included extra-pyramidal effects (N=14), adverse endocrine effects (N=2), weight gain (N=2), paradoxical effects of benzodi-azepine (N=2), constipation (N=1), and seizures (N=1).

Treatments included milieu therapy, regular family visits and consultations, social support when necessary, and medication, as described above. At the end of the hospitalization, the mean GAS score was 26.9 (±8), which translates to an average of 40% improvement.

Explicative variables of improvement at discharge and length of hospitalization

We assessed whether independent variables (e.g., age, sex, socio-economic status, family ethnic origin, episode causes (no treatment/maladaptive/organic/psychiatric), level of ID, history of an organic developmental disorder, and CARS and GAS scores at intake) affected the length of hospitalization and improvement at the time of discharge from the hospital [¢GAS]. The variance analysis revealed that the psychiatric cause significantly affected the ¢GAS [F=3.42, p=0.024] and that the level of ID had a significant effect on the duration of hospitalization [F=3.93, p=0.032]. Tukey’s and Bonferroni’s tests were used to compare the different levels of the psychiatric causes and the ID. Patients with a psychiatric cause experienced better clinical improvement than did patients with another cause of the acute state. Furthermore, patients with profound or severe intellectual disability had longer inpatient stays than patients with moderate or mild intellectual disability.

Discussion

The current study provides a detailed clinical picture of a population of adolescents with autism who were hospitalized in a psychiatric setting for acute behavioral impairment or cognitive regression and documents the factors influencing the outcome.

The main limitations of this study are (a) the retrospective design, (b) the lack of standardized instruments to assess patients’ level of intellectual disability or language, and (c) the use of a limited number of clinical instruments [GAS, CARS]. The strengths of this study are (a) the multidisciplinary approach, including the use of experts in epilepsy and genetic/metabolic disease, (b) the free access to inpatient care regardless of patients’ socioeconomic background, and (c) the use of long inpatient stays in an intensive care unit to monitor outcomes of multiple therapeutic techniques for behavioral improvement.

It is noteworthy that the population studied is unique in terms of the severity of the problematic behaviors observed. Indeed, psychiatric hospitalization is quite unusual among people with autism and generally occurs after the failure of first-line interventions, such as behavioral management or an outpatient trial of a psychotropic drug.

Low IQ, absence of communication skills, and comorbid epilepsy are well-known factors leading to a poor prognosis, including an impaired course of development during adolescence (Gillberg and Steffenburg, 1987; Venter et al., 1992; Ballaban-Gil et al., 1996; Rapin, 1997; Howlin et al., 2004). In the current sample, all 29 individuals were severely impaired and had multiple challenging behaviors. This point is not surprising, as it has been shown in adults that these behaviors often co-occur (Matson et al., 2008). All had intellectual disability; all but one had severe autism as measured by the CARS; only a third had functional language; half of them had “syndromal or complex autism” (Cohen et al., 2005; Miles et al., 2005). However, this study also demonstrates that other factors, including specific care, family support, and socio-economic factors, appear to be crucial in the occurrence of these acute states. The male-female ratio was 3.8: 1 in the sample. Given the fact that all of the patients exhibited significant cognitive delay and severe autistic syndrome, the expected sex ratio should be closer to 2: 1 (Fombonne 2003, Amiet et al, 2008). This discrepancy can be explained by the fact that aggressivity and conduct disorders are more frequent among boys. Moreover, challenging behaviors are less tolerable among boys, leading to more frequent hospitalization requirement.

Absence of care was the retained diagnosis for the acute state in about 25% of the cases. This finding highlights two facts. First, adolescence is often a period when a new institution is needed, resulting in a higher risk of a break in the continuity of care (Fombonne et al., 1997). Individuals become too old for children’s institutions, but no adolescent institution exists. Second, as demonstrated in a large naturalistic study that described the follow-up of a cohort of 495 children with PDD, the major risk factor for the absence of appropriate care in France is a high degree of behavioral impairment (Thevenot et al., 2008). Therefore, despite free access to care in France, both adolescence and behavioral impairment may serve as exclusion factors in individuals with PDD. As a result, a vicious circle occurs as the absence of care may increase behavioral impairment.

In addition, the importance of family support is demonstrated by cases in which consequences occurred after major family events. In six cases, a diagnosis of adjustment disorder was retained for the acute state. Poor adaptive skills are a classical feature of both intellectual disability and autism. However, it is noteworthy that the life events implicated in our cases were very severe in nature (death, hospitalization of a parent for psychiatric illness or cancer, and maltreatment) and would also have affected ordinary adolescents.

In four cases, a psychiatric illness was diagnosed. Two adolescents exhibited a severe form of catatonia with akinesia, catalepsy, and mutism. Classically associated with schizophrenia when it occurs in youths (Cohen et al., 2005; Cornic et al., 2009), catatonia can be associated with bipolar disorders (Brunelle et al., 2009), somatic illness (Lahutte et al., 2008), and also autism (Wing and Shah, 2000; Ohta et al., 2006; Cohen et al., 2009). In a clinical follow-up study, Wing and Shah (2000) reported a 6% rate of catatonic episodes in a group of 506 adolescents and adults, especially when subjects had intellectual disability. Only one case of major depressive disorder was reported in our study, but this statistic could be underestimated. There is emerging evidence that depression is probably the most common psychiatric disorder that occurs in autistic people, but this disorder can be difficult to recognize in subjects with autism with intellectual disability and poor communication skills (Kobayashi et al., 1992; Ghaziuddin et al., 2002). It could be hypothesized that some subjects with a diagnosis of adjustment disorder were, in fact, depressed. Finally, one patient had bipolar disorder, a comorbidity that has been reported in association with complex differential diagnosis issues (Atals and Gerbino-Rosen, 1995; Brunelle et al., 2009).

The importance of somatic illness is probably the most significant result in this study. For one-third of the subjects (9 out 29), the acute behavioral state was a consequence of a treatable medical illness. A systematic approach is warranted, given the variety of possible conditions (see below). Among organic conditions, uncontrolled epilepsy should be the first-line hypothesis. Epilepsy was found to be responsible for the acute behavioral deterioration in six of our cases. Three of these received a diagnosis of epilepsy for the first time during the hospitalization. The high prevalence rate in this group is not surprising, given that epilepsy in autism is associated with intellectual disability (Amiet et al., 2008) and that early childhood and adolescence have been reported to be the peak periods for seizure onset (Tuchman and Rapin, 2002). However, the relationship between autism and epilepsy is complex, and their association may have different origins. Various seizure types and epileptic syndromes have been described in association with autism. Moreover, epileptic anomalies are frequently observed on the EEGs of autistic patients despite an absence of seizures, suggesting at least a low epileptic threshold (Tuchman and Rapin, 2002). It may also be true that autism and epilepsy share a genetic and/or neurodevelopmental cause, at least in the case of secondary autism (e.g., tuberous sclerosis). Epilepsy by itself may induce the development of autistic symptoms (Jambaqué et al., 1998). Two examples illustrate this point: (a) autistic regression may occur when the epileptic focus is located in a critical brain area, mainly in temporo-frontal locations, with substantial improvement after medication or even surgical treatment (Nass et al., 1999; Neville et al., 1997); (b) several epileptic encephalopathies are associated with intellectual disability and/or autistic traits, probably through a specific developmental impact. This association is especially true in West syndrome (Saemundsen et al., 2007). Finally, a coincidental association between autism and epilepsy cannot be ruled out in some cases, considering the high frequency of epilepsy in the general population. In terms of the diagnostic and therapeutic approach, we, like others, consider collaboration with an experienced neurologist to be crucial (Tuchman and Rapin, 2002).

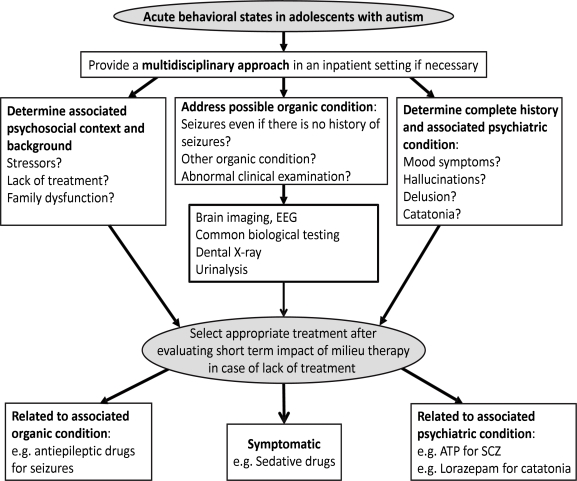

To formulate rational guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute behavioral states or regression in adolescents with autism, one cannot remain at the level of a symptomatic approach. Given the diversity of psychopathologies found in this study, we recommend a systematic integrative multidisciplinary approach that should include (a) a careful social and family evaluation, (b) a systematic search for frequent painful organic conditions, based on a clinical evaluation and a minimal screening [common blood tests, dental X-ray, urinalysis], (c) a neurological examination, with a specific focus on possible seizures, and an EEG, despite the technical issues in this population, and (d) a psychiatric evaluation, taking into account the particular profile of these adolescents [poor language skills, ID] and using adapted rating tools when available. This process should lead to a functional evaluation of each individual case and to the formulation of a principal hypothesis regarding the cause of the acute behavioral state. This step is crucial given the tendency to use too many medications in this field despite the minimal evidence available regarding their effectiveness for challenging behavior associated with autism (Matson and Neal, 2009). Considering alternative psychosocial-based interventions and careful functional assessments appear to be advisable. Figure 2 summarizes our view. Although this view is not a scientific fact and is essentially experience-based, this integrative approach can assist during the process of making treatment decisions.

Figure 2.

Acute behavioral states in adolescents with autism: a multimodal framework for evaluation and treatment.

EEG = electroencephalography; ATP = antipsychotic drug; SCZ = schizophrenia

Conclusion

Adolescents with autism who present with acute behavioral regression that compromises safety need to be examined with a multidisciplinary approach that includes organic, social, and psychiatric investigations. Given the complexity of these situations, hospitalization in psychiatric settings that collaborate with other disciplines is warranted. The adolescent psychiatrist plays a key role in coordinating investigations, giving a proper diagnosis, and treating the acute state.

Acknowledgements/Conflict of Interest

The authors have no financial relationships or conflicts to disclose.

References

- Amiet C, Gourfinkel-An I, Bouzamondo A, Tordjman S, Baulac M, Lechat P, Mottron L, Cohen D. Epilepsy in autism is associated with mental retardation and gender: evidence from a meta-analysis. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64:577–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atals JA, Gerbino-Rosen G. Differential diagnostics and treatment of an inpatient adolescent showing pervasive developmental disorder and mania. Psychological Report. 1995;77:207–210. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1995.77.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballaban-Gil K, Rapin I, Tuchman R, Shinnar S. Longitudinal examination of the behavioral, language, and social changes in a population of adolescents and young adults with autistic disorder. Pediatric Neurology. 1996;15:217–223. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(96)00219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billstedt E, Gillberg IC, Gillberg C. Autism after adolescence: population-based 13- to 22-year follow-up study of 120 individuals with autism diagnosed in childhood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder. 2005;35:351–60. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-3302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E, Bolton P. Episodic psychiatric disorders in teenagers with learning disabilities with and without autism. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;189:361–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.018127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelle J, Consoli A, Tanguy ML, Huynh C, Périsse D, Deniau E, Guilé JM, Gérardin P, Cohen D. Phenomenology, socio-demographic factors and short-term prognosis of acute bipolar disorder in adolescents: a chart review. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;18:185–193. doi: 10.1007/s00787-008-0715-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Nicolas JD, Flament M, Perisse D, Dubos PF, Bonnot O, Speranza M, Graindorge C, Tordjman S, Mazet Ph. Clinical relevance of chronic catatonic schizophrenia in children and adolescents: evidence from a prospective naturalistic study. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;76:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Nicoulaud L, Maturana A, Danziger N, Périsse D, Duverger L, Jutard C, Kloeckner A, Consoli A. The use of packing in adolescents with catatonia: a retrospective study with an inside view. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2009;6:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Pichard N, Tordjman S, Baumann C, Burglen L, Excoffier S, Lazar G, Mazet Ph, Pinquier C, Verloes A, Heron D. Specific genetic disorders and autism : clinical contribution towards identification. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder. 2005;35:103–116. doi: 10.1007/s10803-004-1038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornic F, Consoli A, Tanguy ML, Bonnot O, Périsse D, Tordjman S, Laurent C, Cohen D. (in press). Adolescent catatonia is associated with an increase in mortality and morbidity: evidence from a four-year prospective follow-up study Schizophrenia Research [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E, Du Mazaubrun C, Cans C, Grandjean H. Autism and associated medical disorders in a French epidemiological survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:1561–1569. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8567(09)66566-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E. Epidemiological surveys of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders: an update. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33(4):365–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1025054610557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaziuddin M, Ghaziuddin N, Greden J. Depression in persons with autism: implications for research and clinical care. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder. 2002;32:299–306. doi: 10.1023/a:1016330802348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillberg C, Schaumann H. Infantile autism and puberty. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder. 1981;11:365–71. doi: 10.1007/BF01531612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillberg C, Steffenburg S. Outcome and prognostic factors in infantile autism and similar conditions: a population-based study of 46 cases followed through puberty. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder. 1987;17:273–87. doi: 10.1007/BF01495061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M. Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:212–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jambaqué I, Mottron L, Ponsot G, Chiron C. Autism and visual agnosia in a child with right occipital lobectomy. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1998;65:555–560. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.4.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaunay E, Consoli A, Guile JM, Mazet P, Cohen D. Treatment Refusal in Adolescents with Severe Chronic Illness and Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;15:135–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Ouimette PC, Kelly HS, Ferro T, Riso LP. Test-retest reliability of team consensus best-estimate diagnoses of axis I and II disorders in a family study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1043–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi R, Murata T. Behavioral characteristics of 187 young adults with autism. Psychiatry Clinical Neuroscience. 1998;52:383–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.1998.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi R, Murata T, Yoshinaga K. A follow-up study of 201 children with autism in Kyushu and Yamaguchi areas, Japan. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder. 1992;22:395–411. doi: 10.1007/BF01048242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahutte B, Cornic F, Bonnot O, Soussan N, Amoura Z, Sedel F, Cohen D. Multidisciplinary approach of organic catatonia in children and adolescents may improve treatment decision making. Progress in Neuro–Psycho–pharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2008;32:1393–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson JL, Cooper C, Malone CJ, Moskow SL. The relationship of self-injurious behavior and other maladaptive behaviors among individuals with severe and profound intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disability. 2008;29:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson JL, Neal D. Psychotropic medication use for challenging behaviors in persons with intellectual disabilities: an overview. Research in Developmental Disability. 2009;30:572–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles JH, Takahashi TN, Bagby S, Sahota PK, Vaslow DF, Wang CH, et al. Essential versus complex autism: definition of fundamental prognostic subtypes. American Journal of Medical Genetic A. 2005;135:171–180. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouridsen SE, Rich B, Isager T, Nedergaard NJ. Psychiatric diagnosis in individuals diagnosed with infantile autism as children: a case-control study. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2008;14:5–12. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000308490.47262.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nass R, Gross A, Wisdoff J, Devinski O. Outcome of multiple subpial transections for autistic epileptiform regression. Pediatric Neurology. 1999;21:464–470. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(99)00029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville BG, Harkness WF, Cross JH, Cass HC, Burch VC, Lees JA, Taylor DC. Surgical treatment of severe autistic regression in childhood epilepsy. Pediatric Neurology. 1997;16:137–140. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(96)00297-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordin V, Gillberg C. The long-term course of autistic disorders: update on follow-up studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1998;97:99–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb09970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta M, Kano Y, Nagai Y. Catatonia in individuals with autism spectrum disorders in adolescence and early adulthood: A long-term prospective study. International Review in Neurobiology. 2006;72:41–54. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(05)72003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapin I. Autism. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337:97–104. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707103370206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Lockyer L. A five to fifteen year follow-up study of infantile psychosis. I. Description of sample. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1967;113:1169–82. doi: 10.1192/bjp.113.504.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Greenfeld D, Lockyer L. A five to fifteen year follow-up study of infantile psychosis. II. Social and behavioural outcome. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1967;113:1183–99. doi: 10.1192/bjp.113.504.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saemundsen E, Ludvigsson P, Hilmarsdottir I, Rafnsson V. Autism spectrum disorders in children with seizures in the first year of life – a population-based study. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1724–1730. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Krauss MW, Shattuck PT, Orsmond G, Swe A, Lord C. The symptoms of autism spectrum disorders in adolescence and adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder. 2003;33:565–81. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000005995.02453.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck PT, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Orsmond GI, Bold D, Kring S, Lounds J, Lord C. Changes in autism and maladaptive behaviors in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder. 2007;37:1735–1747. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0307-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shopler E, Reichler RJ, De Velis RF, Daly K. Toward objective classification of childhood autism: Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder. 1980;10:91–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02408436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taieb O, Flament M, Chevret S, Jeammet Ph, Allilaire JF, Mazet Ph, Cohen D. Clinical relevance of ECT in adolescents with severe mood disorder : evidence from a follow-up study. European Psychiatry. 2002;17:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(02)00668-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevenot JP, Philippe A, Casadebaig F.2008Suivi d’une cohorte d’enfants porteurs de troubles autistiques et apparentés en Ile-de-France de 2002 à 2007: situation des enfants lors de l’inclusionavailable online at <http://psydoc-fr.broca.inserm.fr/Recherche/Rapports/InclusionAutistes.pdf>

- Tuchman R, Rapin I. Epilepsy in autism. Lancet Neurology. 2002;1:352–358. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter A, Lord C, Shopler E. A follow-up study of high-functioning autistic children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1992;33:489–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing L, Shah A. Catatonia in autistic spectrum disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;176:357–62. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]