Abstract

Background: Fentanyl buccal soluble film (FBSF) has been developed as a treatment of breakthrough pain in opioid-tolerant patients with cancer. The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of FBSF at doses of 200–1200 μg in the management of breakthrough pain in patients with cancer receiving ongoing opioid therapy.

Patients and methods: This was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-crossover study that included opioid-tolerant adult patients with chronic cancer pain who experienced one to four daily episodes of breakthrough pain. The primary efficacy assessment was the sum of pain intensity differences at 30 min (SPID30) postdose.

Results: The intent-to-treat population consisted of 80 patients with ≥1 post-baseline efficacy assessment. The least-squares mean (LSM ± SEM) of the SPID30 was significantly greater for FBSF-treated episodes of breakthrough pain than for placebo-treated episodes (47.9 ± 3.9 versus 38.1 ± 4.3; P = 0.004). There was statistical separation from placebo starting at 15 min up through 60 min (last time point assessed). There were no unexpected adverse events (AEs) or clinically significant safety findings.

Conclusions: FBSF is an effective option for control of breakthrough pain in patients receiving ongoing opioid therapy. In this study, FBSF was well tolerated in the oral cavity, with no reports of treatment-related oral AEs.

Keywords: breakthrough cancer pain, clinical study, fentanyl buccal soluble film

introduction

Pain related to chronic conditions such as cancer is often characterized by two components. The first component is persistent pain, and the recommended treatment is long-acting opioid products. The second component is often referred to as ‘breakthrough pain’. Breakthrough pain is defined as the ‘transient exacerbation of pain occurring in a patient with otherwise controlled persistent pain’ [1]. An international survey of 58 clinicians in 24 countries evaluated a total of 1095 patients with cancer pain of an intensity that needed treatment with opioid analgesics to determine the prevalence of breakthrough pain [2]. Breakthrough pain was reported in 64.8% of these patients and was associated with higher pain scores and functional impairment on the Brief Pain Inventory [2].

Breakthrough pain episodes have been routinely treated with oral short-acting opioids, including hydrocodone, hydromorphone, morphine, and oxycodone [3]. Although these treatments are widely used, the variable absorption of oral opioids from the gastrointestinal tract may result in delayed pain relief (PR) (up to 40 min after administration) [4] and may lead to variability in the therapeutic effect. In a Pan-European survey [5], it was reported that 63% of patients with cancer receiving prescription analgesics reported breakthrough pain or inadequate PR. Of those patients, 58% reported that they had inadequate PR at all times.

As an alternative to oral administration, transdermal and transmucosal routes of administration have been used to deliver pain medication. With transmucosal delivery, absorption through the oral mucosa from either the buccal cavity or sublingually is more rapid than oral absorption [6]. Other benefits of oral transmucosal delivery include minimization of first-pass metabolism and better tolerance for patients with dysphagia (especially dysphagia due to conditions such as head and neck cancer [7]) or those who have experienced nausea or vomiting [8].

Fentanyl is a potent opioid analgesic that is well absorbed via the oral mucosa. Currently, there are various formulations approved by regulatory authorities. Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate (OTFC) (United States and Europe: Actiq®; Cephalon, Inc., Frazer, PA) is a buccal formulation composed of a fentanyl lozenge on a stick. This formulation requires patient effort for administration, and absorption is dependent on the individual application technique. A second buccal formulation, the fentanyl buccal tablet (FBT) (United States: Fentora®; Europe: Effentora®; Cephalon), has been approved in the United States and Europe. This formulation utilizes an effervescence reaction that is postulated to be responsible of an enhanced fentanyl absorption through the buccal mucosa above that achievable with OTFC. More recently, a sublingual tablet formulation of fentanyl (Europe: Abstral®; Orexo, Inc., Uppsala, Sweden) that uses mucoadhesives to hold the fentanyl in contact with the mucosa membrane has been marketed in Europe.

The most recent product to be approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration, a fentanyl buccal soluble film (FBSF) (United States: Onsolis®; Meda Pharmaceuticals Inc., Somerset, NJ; Europe: Breakyl® and Buquel®), has been developed to control breakthrough pain in patients with cancer and is intended for direct application to the oral mucosa. FBSF utilizes BioErodible MucoAdhesive (BEMA™; BioDelivery Sciences, Inc., Raleigh, NC) technology to deliver fentanyl across the buccal mucosa. The technology uses a dual-layer polymer film consisting of a mucoadhesive layer that contains the active drug and an inactive layer that helps to prevent diffusion of drug into the oral cavity. The mucoadhesive layer adheres to a moist mucosal membrane in seconds. FBSF starts to dissolve in minutes and is completely dissolved within 15–30 min after application without patient effort, requiring only a minimal amount of saliva to dissolve once adhered. Previous studies have shown that when delivered by this system, the proportion of the fentanyl dose that undergoes transmucosal absorption is ∼50% and the absolute bioavailability is ∼71%. The direct relationship between the surface area of the dose unit and the dose of fentanyl combined with the mucosa contact time results in consistent plasma concentrations when equivalent doses are delivered by single or multiple dosage units [9].

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of FBSF at doses ranging from 200 to 1200 μg in the management of breakthrough pain in patients with cancer receiving around the clock opioid therapy.

methods

trial design

This was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study comparing FBSF with placebo for the treatment of breakthrough pain in patients with cancer receiving a stable opioid regimen for persistent pain. Breakthrough pain was defined as moderate-to-severe pain that occurred at a specific site for a transitory period against a background of persistent pain controlled by the around the clock opioid regimen. The study consisted of a screening period of up to 1 week, an open-label titration period of up to 2 weeks, a double-blind period of up to 2 weeks, and a 1-day follow-up. In the titration period, patients were issued an electronic diary and a dose-titration kit containing five doses of each of the five dose strengths (200, 400, 600, 800, and 1200 μg) of FBSF. Each subject started with the 200-μg dose and increased their dose in a stepwise manner until adequate PR was achieved. Patients unable to identify a dose that produced satisfactory PR and those not completing the titration within 2 weeks were discontinued from the study. Patients who identified a dose that produced satisfactory PR for at least two target breakthrough pain episodes were eligible to enter the double-blind crossover period. During the double-blind period, patients received nine doses of study medication: six contained fentanyl at the effective dose for that patient and three were placebo. The order in which the patient received FBSF or placebo was determined by a computer-generated randomization code. At no time did patients receive two placebos in a row. Subjects were allowed to use their usual rescue medication if adequate PR was not realized within 30 min. Patients were not allowed to take another study dose for 4 h after their last dose of study drug. Any subsequent dose of study medication was for the emergence of a new target breakthrough pain episode and not an unresolved previously treated episode. Subjects remained in the double-blind period of the study until all nine doses of study medication were taken or until 14 days after entry into the double-blind period of the study.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating center. The study was conducted in accord with provisions of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and its most recent amendment concerning medical research in humans (2004) and conformed to all local laws and regulations (whichever provided the greater protection to individual patients). Documentation and procedures complied with the International Conference on Harmonisation Guideline E6 (R1) and the USA Code of Federal Regulations (Title 21, Part 50). All patients read and signed an approved informed consent form before enrollment procedures commenced.

patients

inclusion criteria.

Patients eligible for the study were men or nonpregnant nonlactating women aged 18 years or older with pain associated with cancer or cancer treatment that required opioid therapy. The opioid dosage regimen must have been stable at the time of enrollment and was required to be equivalent to 60–1000 mg/day of oral morphine or 50–300 μg/h of transdermal fentanyl. Eligible patients were experiencing one to four episodes of breakthrough pain daily that required opioids for pain control, for which opioids provided at least partial relief.

exclusion criteria.

Patients with more than four episodes of breakthrough pain per day and those with rapidly escalating pain that the investigator believed may require an increase in the dosage of the background opioid were not eligible for the study, as were those who had received strontium 89 during the previous 6 months and those receiving any other therapy that could alter pain or the patient’s response to pain medication.

drug administration

Eligible patients received instruction on handling and application of FBSF dose units. Patients were instructed to apply the mucoadhesive side of the thin film unit (about half the thickness of a business card or roughly equivalent to 2.5 dollar bills) to a moistened (saliva or water) buccal mucosa and to hold it in place for 5 s. The FBSF dose unit adheres to the mucosal membrane, becoming pliable within a minute, and then completely dissolves over a period of ∼15–30 min.

Patients were allowed to use their usual rescue medication 30 min after self-administration of a study dose for episodes of pain that were not adequately controlled by the study medication.

assessments

efficacy.

Pain intensity (PI) and PR were assessed at 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min after each double-blind study dose. PI was measured on an 11-point scale (0 = no pain and 10 = worst pain) and the PI difference calculated as the baseline PI minus the assessment point PI. PR was measured on a 5-point scale (0 = no relief to 4 = complete relief). PI differences (PID = baseline PI minus PI at assessment point) were calculated, and the weighted sum over the first 30 min postdose (SPID30) was defined as the primary outcome measure. Secondary outcome measures included PID and PR calculated at various time points throughout the study period and the sums of PID (SPID) were calculated over various intervals. Global satisfaction was assessed on a 5-point scale (poor, fair, good, very good, and excellent) at the time of rescue or 60 min after study dose.

safety.

A complete medical history, including cancer diagnosis, recent therapeutic decisions, and drug history, was assessed at the screening visit. A complete physical examination was carried out and vital signs measured at the screening and follow-up visits. Adverse events (AEs) were reported and assessed throughout the study with an electronic diary. Concomitant medications were monitored throughout the study.

statistical analyses

Efficacy analyses were conducted using the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, defined as all patients who entered the double-blind phase of the trial, who took at least one dose of study medication and had at least one pain assessment within the 30-min postdose period. The safety population was defined as all patients who received at least one dose of study medication in the dose-titration and double-blind treatment phases of the study.

All statistical analyses were carried out by using a two-sided hypothesis test with a type I error (alpha) of 0.05 (i.e., a 5% level of statistical significance). Efficacy data are presented as least-squares means (LSM) and standard errors. The primary efficacy parameter, SPID30, was analyzed using a mixed model of repeated measures with fixed effects for treatment, pooled site, and a random effect for subjects. The secondary efficacy parameters were analyzed using the one-sample Wilcoxon signed rank test.

results

patient disposition and demographics

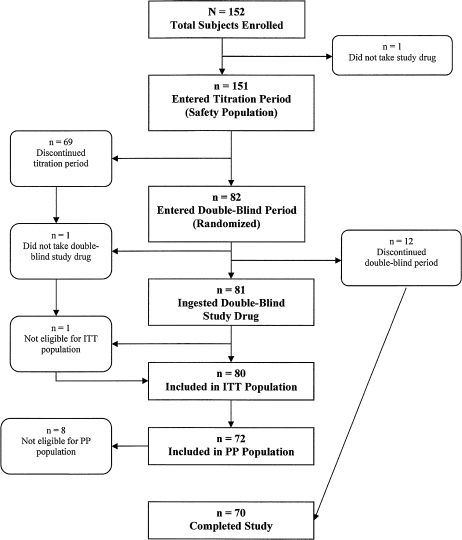

The study was conducted at 30 clinical sites in the United States between 24 February 2006 and 14 March 2007. A total of 152 patients were screened and enrolled in the study, and 151 patients received at least one dose of study medication and were included in the safety population (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of patients through the study. ITT, intent-to-treat; PP, per protocol.

Of the 151 patients enrolled in the titration phase, 69 (45.7%) discontinued the study. The reasons for withdrawal were the following: 17 (11.3%) for AEs, 15 (9.9%) because of difficulties or noncompliance with the electronic diary, 14 (9.3%) withdrew consent without explanation, 8 (5.3%) were withdrawn for protocol violations, 7 (4.6%) because they had less than a single episode of breakthrough pain a day, 5 (3.3%) for lack of efficacy, and 3 (2.0%) patients for administrative reasons.

Twelve patients (7.9%) discontinued prematurely from the double-blind phase of the study for the following reasons: 4 (4.9%) withdrew consent, 3 (3.7%) because of AEs, 2 (2.4%) for noncompliance with the electronic diary, 2 (2.4%) for not consistently treating one episode of pain per day, and 1 (1.2%) for lack of efficacy.

A total of 70 patients in the safety population did not receive any study drug in the double-blind treatment phase of the study, and 1 patient did not have a pain assessment within 30 min of taking a dose of study drug during the double-blind phase of the study; thus, the ITT population consisted of 80 patients.

A summary of the demographic characteristics of patients included in the safety and efficacy populations is provided in Table 1. There were no important differences in the baseline characteristics of the safety and ITT populations. Breast cancer (23%), lung cancer (17%), colorectal cancer (11%), gastroesophageal cancer (7%), pancreatic cancer (6%), and head and neck cancer (5%) were the most common cancer types in the safety population. Overall, patients had suffered from the current primary cancer for a mean period of 3.2 years with a median of 1.6 years and a range of <1 to >30 years. More than half of the patients (55.6%) had received chemotherapy and one-quarter (25.2%) had received radiation therapy in the last 6 months before study entry.

Table 1.

Demographic data

| Demographic | Safety population (n = 151) | Efficacy (ITT) population (n = 80) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 66 (44) | 36 (45) |

| Female | 85 (56) | 44 (55) |

| Mean (SD) age in years | 57.1 (12.2) | 56.8 (13.0) |

| Age in years, n (%) | ||

| <65 | 104 (69) | 55 (69) |

| ≥65 | 47 (31) | 25 (31) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 131 (86.8) | 72 (90.0) |

| Black | 12 (7.9) | 6 (7.5) |

| Asian | 1 (0.7) | 0 |

| Other | 7 (4.6) | 2 (2.5) |

| Mean (SD) height, cm | 168.7 (9.8) | 169.2 (9.3) |

| Mean (SD) weight, kg | 73.0 (19.1) | 74.5 (17.8) |

| Mean (SD) duration since diagnosis in years | 3.2 (4.5) | 3.7 (5.2) |

| Median (range) duration since diagnosis in years | 1.6 (0.0–30.3) | 2.17 (0.0–30.3) |

| Cancer treatment in previous 6 months, n (%) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 84 (56) | 43 (54) |

| Radiation | 38 (25) | 15 (19) |

ITT, intent-to-treat; SD, standard deviation.

For approximately half of the patients in the safety population, the pain pathophysiology for both persistent pain and target breakthrough pain was somatic and/or visceral. Forty-nine patients (32.5%) also experienced neuropathic pain. For most patients in the safety population, the pain syndrome for persistent and target breakthrough pain was typically related to direct tumor involvement (84.8% and 86.1% of patients, respectively) or due to somatic/visceral lesions (83.4% and 84.8% of patients, respectively).

The most common stable opioid regimen was transdermal fentanyl for persistent pain, taken by 46.4% of patients, and hydrocodone for target breakthrough pain, taken by 42.4% of patients. Long-acting oral morphine was used in 23.8% of patients for persistent pain and short-acting oral morphine was used in 26.5% of patients for target breakthrough pain. For nearly all patients [149 of 151 (98.7%)] in the safety population, there were minimal opioid side-effects from the current daily opioid dose.

dosing

Patients received a mean of 9.3 doses of FBSF during the dose-titration phase. During the double-blind treatment phase, patients received a mean of 5.5 doses of FBSF and 2.8 doses of placebo. Patients received a total of 14.0 doses of FBSF over the course of the study.

In the double-blind portion of the study, the number of individuals dosed at 200, 400, 600, 800, or 1200 μg was 4 (4.9%), 15 (18.5%), 23 (28.4%), 19 (23.5%), and 20 (24.7%), respectively. The effective dose for most patients was ≥400 μg. The mean duration of exposure to the study drug was 6.6 days in the titration period, 5.9 days in the double-blind period, and 10.1 days in the entire study period. The minimum period of exposure was 1 day and the maximum was 27 days.

efficacy

At baseline, the mean PI score was 6.9 and the median PI score was 7.0 for both FBSF- and placebo-treated episodes. A total of 394 FBSF episodes and 197 placebo episodes were included in the ITT analysis of the primary efficacy end point.

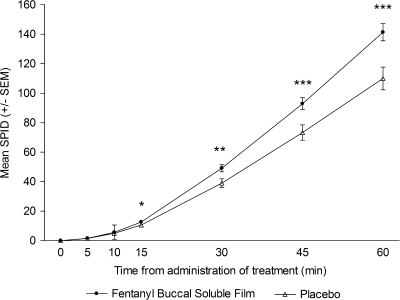

The LSM ± SEM of the SPID30, the primary efficacy variable, was significantly greater for FBSF-treated episodes of breakthrough pain than for placebo-treated episodes (47.9 ± 3.9 versus 38.1 ± 4.3; P = 0.004). The SPID values for FBSF-treated episodes were consistently greater compared with placebo-treated episodes at all postdose time points. There was statistically significant separation from placebo starting at 15 min postdose (P < 0.05) through 60 min postdose [the last time point assessed (P < 0.001)] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean sum of pain intensity difference (SPID) scores over time.*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. SEM, standard error of the mean.

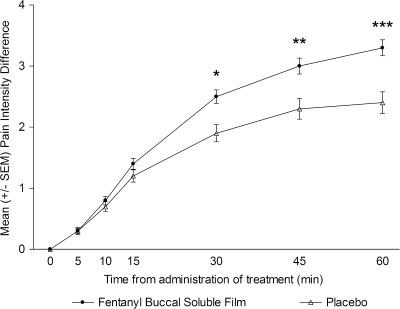

Similarly, PID (Figure 3) values for FBSF-treated episodes were consistently greater compared with placebo-treated episodes at 10 min postdose and all time points beyond, with the difference reaching statistical significance at 30 min. The PR values were statistically significant from placebo starting at 30 min postdose (P < 0.01) and continuing until the last assessment (P < 0.01).

Figure 3.

Mean pain intensity difference over time.*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. SEM, standard error of the mean.

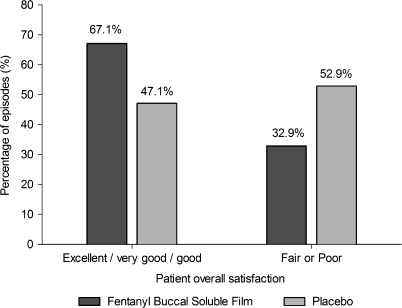

The percentage of episodes with a 33% or 50% decrease in pain was also significantly greater with FBSF than with placebo (Table 2). Overall satisfaction with the study drug was significantly greater with FBSF than with placebo (mean score 2.0 versus 1.5, respectively; P < 0.001). Moreover, more patients rated their overall satisfaction with FBSF as good, very good, or excellent compared with placebo (Figure 4). Conversely, fewer patients rated their overall satisfaction with FBSF as poor or fair compared with placebo (Figure 4). The mean (± SEM) number of episodes when rescue medication was used was significantly lower after treatment with FBSF than with placebo (30.0% ± 3.5% versus 44.6% ± 4.4%; P = 0.002).

Table 2.

Percentage of episodes with decreases in pain scores (mean ± SEM)

| Parameter | Treatment | Time post-administration (min) |

|||

| 15 | 30 | 45 | 60 | ||

| Percentage of episodes with ≥33% reduction in pain scores | FBSF | 26.4 (3.55) | 47.3 (4.05) | 57.5 (3.93) | 64.3 (3.72) |

| Placebo | 21.3 (3.66) | 38.2 (4.45) | 46.5 (4.50) | 48.2 (4.51) | |

| P value | 0.100 | 0.009 | 0.004 | <0.001 | |

| Percentage of episodes with ≥50% reduction in pain scores | FBSF | 14.9 (2.81) | 32.8 (3.78) | 41.1 (4.11) | 46.3 (4.17) |

| Placebo | 14.7 (3.35) | 24.1 (3.87) | 30.5 (4.10) | 34.0 (4.30) | |

| P value | 0.963 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.005 | |

FBSF, fentanyl buccal soluble film.

Figure 4.

Overall satisfaction with study drug.

safety

Twenty-three patients (15.2%) experienced 29 serious AEs. None of these serious AEs were considered to be related to the study drug. Respiratory depression was not reported by any patient enrolled in the study. There were four deaths during the study, none of which were considered to be study drug related.

Twenty-one patients (13.9%) discontinued study drug administration because of treatment-emergent AEs, including 9 serious AEs and 12 nonserious AEs. Nausea and vomiting were the most common AEs leading to permanent study drug discontinuation (3.3% of patients, respectively).

Treatment-emergent AEs were reported by 75 patients (49.7% of 151 patients) during the titration period and 34 patients (42% of 81 patients) during the double-blind period. The most common treatment-emergent AEs were typical of opioid administration and occurred with similar frequency during the titration and double-blind phases. Treatment-emergent AEs reported during the titration phase included nausea (9.3%), vomiting (9.3%), somnolence (6.0%), dizziness (4.6%), and headache (4.0%). Treatment-emergent AEs reported during the double-blind phase included nausea (9.9%), vomiting (9.9%), and headache (1.2%).

Most AEs [213 of 273 (78.0%)] in 47 patients were not considered to be drug related. A total of 56 drug-related AEs were reported by 37 of the 151 patients (24.5%) included in the safety population. One patient had four AEs, and it could not be determined whether those events were drug related. The most common drug-related AEs were gastrointestinal disorders and central nervous system disorders (Table 3). These AEs included somnolence (6.0%), nausea (5.3%), dizziness (4.6%), and vomiting (4.0%). These AEs are commonly associated with opioid therapy.

Table 3.

Incidence of drug-related adverse events that occurred in two or more patients (n = 151)

| Adverse event | Incidence, n (%) |

| Somnolence | 9 (6.0) |

| Nausea | 8 (5.3) |

| Dizziness | 7 (4.6) |

| Vomiting | 6 (4.0) |

| Headache | 4 (2.6) |

| Constipation | 3 (2.0) |

| Dry mouth | 2 (1.3) |

| Dysgeusia | 2 (1.3) |

| Pruritus | 2 (1.3) |

| Confusional state | 2 (1.3) |

Only five patients (3.3%) reported oral AEs (n = 2, mild mucosal inflammation; n = 3, oral candidiasis) and all these events were considered to be unrelated to study treatment in the opinion of the investigator. No oral ulcerations, pain, or edema associated with the study drug were observed in the study population.

discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that FBSF is more effective than placebo for the management of breakthrough pain in opioid-tolerant patients with cancer. The SPID values were significantly greater for FBSF-treated episodes than for placebo-treated episodes beginning 15 min after drug administration and continuing through 60 min. Similarly, pain scores for FBSF-treated episodes were significantly lower than for placebo-treated episodes at 30, 45, and 60 min after dosing. At 30 min postdose, reductions in PI of at least 33% and of at least 50% were obtained in significantly more FBSF-treated episodes than in placebo-treated episodes (P = 0.009 and P = 0.002, respectively). Patients gave favorable ratings to a numerically higher proportion of pain episodes treated with FBSF than with placebo (P < 0.001).

Of 152 patients on stable opioid therapy for cancer pain who entered the dose-titration phase of the study, 53.9% entered the double-blind phase. The most common reasons for dropout from the titration phase were noncompliance with study procedures, including use of the electronic diary card. Of the subjects who began titration, 3.3% did not continue in the study because they were not able to find an effective dose of FBSF for breakthrough pain.

It has been reported that more than half of patients receiving prescription medicine for cancer pain experience inadequate PR or breakthrough pain [5]. This finding indicates that additional pharmacotherapeutics that are well tolerated and have rapid onsets of action are needed to treat this patient population. Transmucosal fentanyl preparations are approved in the United States for the treatment of breakthrough pain in patients with cancer, including OTFC, FBT [10, 11], and FBSF. OTFC has been shown to provide more effective PR than immediate-release morphine in a study population similar to the group described in the current study [12]. FBSF has been shown to produce plasma fentanyl concentrations earlier and greater than an equal dose of OTFC in normal volunteers [13].

FBSF was safe and well tolerated by patients enrolled in this study. The AEs reported during the study were typical of those associated with opioid analgesics. No patients experienced respiratory depression and none of the serious AEs were considered to be study drug related. No drug-related oral AEs were reported in this study. The dropout rate observed in this study due to treatment-emergent AEs was 13.9%. Five patients (3.3%) withdrew due to lack of efficacy during the open-label titration phase and one patient (1.2%) withdrew due to lack of efficacy during the double-blind phase. No patients dropped out due to site administration AEs.

There are several important clinical implications of the results reported here. There was a statistically significant decrease in SPID compared with placebo as early as 15 min after drug administration and continuing through 60 min; thus, FBSF provides rapid effective relief of breakthrough pain in patients with cancer. FBSF is safe and well tolerated, with no oral AEs attributed to the drug. There was a low rate of failure to control pain in these patients. These findings are of particular importance considering the special needs of patients with cancer who may have trouble swallowing, mucosal problems (mucositis and thrush), or xerostomia.

One interesting aspect of this study was the unusual placebo response to the film. When the results of the study of FBT by Portenoy et al. [14] are compared with that in the FBSF study, it is apparent that the response to placebo was consistently higher in our trial [e.g., placebo PID at 30 min was 36% higher in this trial than in the buccal tablet trial (1.9 versus 1.4)]. The reason for the higher placebo response in a similar patient population is not readily apparent, but there are several possibilities. Placebo rates tend to be high in pain studies, with estimates ranging from 15% to 53% [15], and expectation plays an important role in their magnitude [16–18]. In this sense, the innovative and unconventional technology of FBSF might have generated high expectations in both investigators and patients and contributed to the high placebo response rate. Specifically, the bilayer delivery technology used for FBSF incorporates the fentanyl into the layer that adheres to the buccal mucosa and isolates the fentanyl from the saliva by the inactive layer that contains the taste masking agents. It is believed that this design not only optimizes fentanyl delivery across the buccal mucosa but also minimizes fentanyl contact with the taste buds, making it very difficult for most patients to distinguish between active and placebo treatments based on taste.

This study has the limitation of being done in an enriched population of patients, those who responded during the open-label titration phase of the study. Thus, our results may not apply to all patients seen in clinical practice. However, there was a low rate of failure to control pain in patients who continued into the double-blind phase of the study.

In conclusion, FBSF is an effective option for control of breakthrough pain in patients receiving ongoing opioid therapy. In this study, FBSF was well tolerated and there were no reports of treatment-related AEs.

funding

BioDelivery Sciences International.

disclosure

LNG and IT are employees of Meda Pharmaceuticals. ALF is an employee and shareholder of BioDelivery Sciences International, the developer of FBSF.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance was provided by Blair J. Jarvis, MSc, M. K. Grandison, PhD, and Carol A. Lewis, PhD.

References

- 1.Portenoy RK, Hagen NA. Breakthrough pain: definition, prevalence and characteristics. Pain. 1990;41:273–281. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90004-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caraceni A, Martini C, Zecca E, et al. Breakthrough pain characteristics and syndromes in patients with cancer pain. An international survey. Palliat Med. 2004;18:177–183. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm890oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrar JT, Cleary J, Rauck R, et al. Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate: randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial for treatment of breakthrough pain in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:611–616. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.8.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.William L, Macleod R. Management of breakthrough pain in patients with cancer. Drugs. 2008;68:913–924. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breivik H, Cherny N, Collett B, et al. Cancer-related pain: a pan-European survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1420–1433. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welling P. Pharmacokinetics: Processes, Mathematics and Applications. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Conno F, Groff L, Brunelli C, et al. Clinical experience with oral methadone administration in the treatment of pain in 196 advanced cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2836–2842. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.10.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang H, Zhang J, Streisand JB. Oral mucosal drug delivery: clinical pharmacokinetics and therapeutic applications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41:661–680. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200241090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasisht N, Stark J, Finn A. BEMA fentanyl shows a favorable pharmacokinetic profile and dose linearity in healthy volunteers. 2008 Annual General Meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anesta Corp. Actiq (Fentanyl Citrate) Oral Transmucosal Lozenge. Prescribing Information. Revised. Actiq (Fentanyl Citrate) Oral Transmucosal Lozenge [Prescribing information]. Frazer, PA: Cephalon, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cephalon Inc. Fentora (Fentanyl Buccal Tablet). Prescribing Information. Revised. Actiq (Fentanyl Citrate) Oral Transmucosal Lozenge [Prescribing information]. Frazer, PA: Cephalon, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coluzzi PH, Schwartzberg L, Conroy JD, et al. Breakthrough cancer pain: a randomized trial comparing oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate (OTFC) and morphine sulfate immediate release (MSIR) Pain. 2001;91:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasisht N, Gever LN, Tagarro I, Finn AL. Formulation selection and pharmacokinetic comparison of fentanyl buccal soluble film with oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate: a randomized, open-label, single-dose, crossover study. Clin Drug Investig. 2009;29(10):647–654. doi: 10.2165/11315300-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Portenoy RK, Taylor D, Messina J, Tremmel L. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of fentanyl buccal tablet for breakthrough pain in opioid-treated patients with cancer. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:805–811. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210932.27945.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beecher HK. The powerful placebo. J Am Med Assoc. 1955;159:1602–1606. doi: 10.1001/jama.1955.02960340022006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enck P, Benedetti F, Schedlowski M. New insights into the placebo and nocebo responses. Neuron. 2008;59:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finniss DG, Benedetti F. Mechanisms of the placebo response and their impact on clinical trials and clinical practice. Pain. 2005;114:3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benedetti F. Mechanisms of placebo and placebo-related effects across diseases and treatments. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:33–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]