Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the functional outcomes of persons who underwent simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty (TKA) compared to subjects who underwent unilateral TKA and a healthy control group. Fifteen subjects who underwent primary bilateral TKA and 15 sex, age, and body mass index-matched subjects who underwent primary unilateral TKA were observed prospectively for 2 years. Subjects in both surgical groups showed significant improvement in Knee Outcome Scores, Short Form 36 physical component scores, Timed Up and Go, and stair-climbing tasks (P ≤ .004). No differences in final outcomes were found between surgical groups. In addition, most 2-year clinical measures were no different between the surgical and control groups. Subjects medically appropriate for bilateral TKA should be afforded this option.

Keywords: bilateral, knee, arthroplasty, outcomes, function

Currently, the lifetime risk of developing symptomatic knee osteoarthritis (OA) is approximately 50% [1]. Knee OA is a leading cause of disability in persons in the United States, and this is only projected to increase with an aging and overweight population [2]. Although most total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) are unilateral, there is a high incidence of bilateral knee disease. Ten years after a primary TKA, the incidence of the cognate knee joint requiring surgical intervention for end-stage OA is 37% [3]. Although unilateral TKA has been shown to be an effective surgical intervention for management of knee OA symptoms, the short-term and long-term outcome for bilateral TKA has been debated. There is currently not a clear consensus on the benefits of performing simultaneous bilateral TKA.

Proponents of simultaneous bilateral TKA argue that performing the surgery decreases rehabilitation time when compared to unilateral TKAs performed at separate times [4]. Furthermore, proponents of simultaneous bilateral TKA will argue the surgery carries no more risk for postoperative complications than unilateral TKA [5–7]. The functional outcomes and patient satisfaction scores are comparable, or higher, in persons undergoing bilateral vs unilateral TKA, and this occurs without a subsequent increase in out-of-pocket or insurance-covered medical expenses [4,8]. Opponents of simultaneous bilateral TKA contend the procedure carries a higher mortality rate than staged bilateral TKA [9]. Other opponents of simultaneous bilateral TKA cite an increase in postoperative complications and higher rehabilitation costs [10–12]. Many of these studies, however, have overlooked long-term functional outcomes and did not account for the medical complications and rehabilitation costs associated with a secondary staged surgery in the contralateral knee joint.

Although many of the studies examining differences between unilateral and bilateral TKA have focused on short-term postoperative outcomes, costs, and complications, few have examined the long-term functional benefits of either surgery. The principal determinant of functional ability 3 years after a primary TKA is the strength of the nonoperated knee [13]. This suggests that the disease progression in the nonoperated limb affects a person’s long-term functional outcome after a unilateral TKA. It can be supposed that functional outcomes after a simultaneous bilateral TKA would not decrease due to weakening or disease progression of a single side because the diseased joint was replaced bilaterally. This may lead to better long-term functional ability in a cohort of persons receiving bilateral TKA.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the longitudinal functional outcomes from a cohort of patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral TKA compared to an age, sex, and body mass index (BMI)-matched cohort of persons who underwent primary unilateral TKA and a healthy control sample group. We hypothesized that self-reported and objective functional measures will be comparable between groups at a 2-year follow-up. In addition, we hypothesized that bilateral and unilateral TKA will result in similar functional outcomes for the duration of the 2-year follow-up.

Materials and Methods

Fifteen subjects who underwent simultaneous bilateral knee arthroplasty were observed prospectively for a period of 2 years. Decision to undergo simultaneous bilateral TKA was made by the patient and surgeon and was primarily based on the presence of severe bilateral knee symptoms at the time prior surgery. Subjects in this group were age, sex, and BMI matched to subjects from a larger cohort of subjects who underwent primary unilateral TKA. This provided an equal sample of 15 subjects in each of the 2 groups. A group of 21 healthy control subjects without symptomatic evidence of orthopedic disease comprised the control group. All subjects had no history of neurologic or cardiopulmonary disease and had no evidence of other lower extremity orthopedic impairment. Subjects in the unilateral TKA group all reported maximal pain in the nonsurgical limb of less than or equal to 4 of 10 during daily activities. All subjects were informed of the risks and benefits of participation and signed an informed consent form approved by the Human Subjects Review Board. Subject demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Subject Demographics are Presented as the Mean for Each Group

| Bilateral | Unilateral | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample (n) | 15 | 15 | 21 |

| Males (n) | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Age (y) | 61.9 | 62.9 | 62.3 |

| 7.0 | 7.2 | 9.0 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.2 | 31.0 | 26.9 |

| 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.5 | |

| Height (m) | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

Standard deviations are given in italics below the mean.

In the TKA groups, self-reported and objective functional measures were obtained from all subjects before surgery and at 3 different time points after TKA. Data were collected at initial physical therapy evaluation and then at 1 year and 2 years after initial evaluation. For the control group, these measures were recorded at one time point and reevaluated 2 years later. Self-reported functional measures consisted of the Knee Outcome Score Activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS) and the Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form 36 physical component summary (PCS). The KOS has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure to evaluate self-perceived functional abilities in persons with knee pathologic condition [14,15]. It is a self-administered questionnaire that consists of 14 questions pertaining to limitations on activities of daily living imposed by symptoms of the knee disorder. Grading for each question is on a 6-point scale (0–5), and the aggregate total is represented at a percentage of the highest possible score of 70.

The Short Form 36 is a generic health status index and has been used in persons with knee OA and those who have undergone TKA [16,17]. The PCS portion of the survey represents an individual’s perception of their physical health. The scores are based on normative values for the US population, and a score of 50 with an SD of 10 represents the average of persons in the United States. This test has also been shown to be a reliable measure of a person’s self-perceived physical status [18,19].

Objective clinical tests used to measure function were the Timed Up and Go (TUG) and the stair-climbing task (SCT). The Timed Up and Go is a functional test that begins with the subjects seated in a chair. When the investigator says “Go,” the subjects rise from the chair, walk 3 meters, turn around, and return to the chair. The time for completion is recorded and begins with the “go” command from the investigator and terminates when the subject returns to a fully seated position. Subjects are permitted to use the arms of the chair during sitting and returning to sit. This test has excellent interrater and intrarater reliability (intraclass coefficient = 0.99) in older adults [20]. The stair-climbing task is a measure of a person’s ability to ascend and descend 12 steps with the use of a handrail for minimal support if needed. As with the TUG, the timing begins on the investigator’s command and terminates when the subject returns with both feet to the ground level. For both the TUG and SCT, subjects were permitted one practice trial and then the average of the subsequent 2 tests were taken and used for the analysis.

Subjects in both the bilateral TKA and unilateral TKA group underwent similar postoperative physical therapy regimens. Subjects from both groups were seen at the same therapy clinic 2 to 3 times per week for 6 weeks, providing a total of 16 to 18 visits. Exercises during the therapy sessions consisted of progressive strengthening exercises, modalities to control swelling and pain, functional activities, and manual therapy to improve range of motion. Both groups also received electrical stimulation to improve quadriceps function, although the bilateral group only received electrical stimulation to the weaker of the 2 legs.

For the TKA groups, independent t tests were used to evaluate differences between groups before surgery, at initial physical therapy evaluation and at 1-year and 2-year follow-ups. Comparisons were made for the KOS, PCS, TUG, and SCT. Mean values and SDs were reported for each group. Comparisons were made for the same variables between all 3 groups using a repeated measures analysis of variance with follow-up independent t tests to determine significant differences between groups.

Results

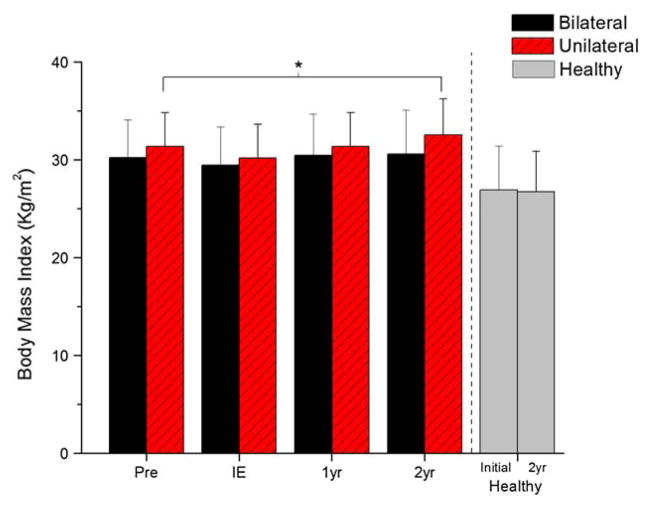

No differences between surgical groups were found before bilateral or unilateral TKA for subject age, BMI, weight, or height (Table 1). Data were collected a mean of 8.1 ± 4.6 days before surgery for the bilateral group and 15.1 ± 16.8 days prior for the unilateral TKA group (P = .193). No differences existed in the time from surgery to initial physical therapy evaluation. Individuals in the bilateral TKA group were seen an average of 26.3 ± 3.3 days after surgery, similar to the unilateral mean of 29.6 ± 6.3 days (P = .123). Persons in both the bilateral and unilateral TKA groups had significantly higher BMI compared to the control group before surgery and at 2-year follow-up (P ≤ .028) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Subjects in the unilateral group showed a significant increase in BMI at the 2-year follow-up when compared to the preoperative values (P = .003). Both the bilateral TKA and unilateral TKA group had higher BMIs at preoperative and 2-year follow-up (P ≤ .028).

The unilateral group showed a significant increase in BMI between preoperative values and the 2-year follow-up (Fig. 1). No differences were found in BMI for the bilateral or control group after 2 years. The mean BMI increase was 0.3 kg/m2 for the bilateral group (P = .63), compared to an increase of 1.6 kg/m2 for the unilateral group (P = .003). This corresponded to a weight gain of 1.0 ± 6.6 kg (P = .57) in the bilateral group and 4.8 ± 5.0 kg (P = .003) in the unilateral group.

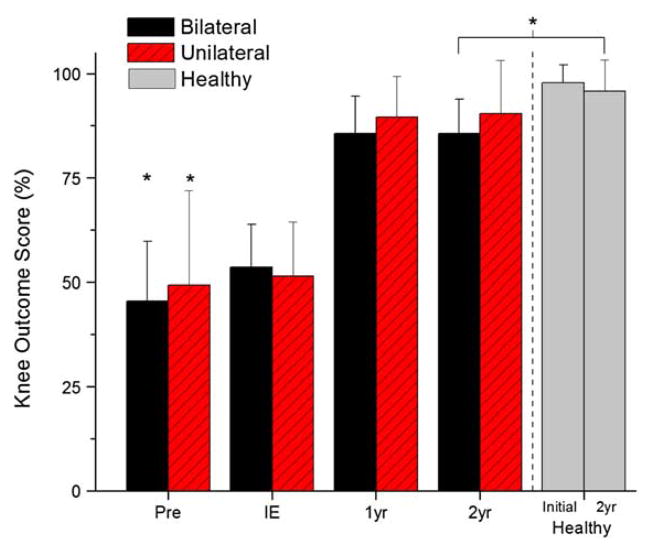

No significant differences existed between the unilateral and bilateral groups at any of the time points for the self-perceived and objective clinical measures (Figs. 2–5). Significant differences did exist between both surgical groups and the control group at the first time point (preoperatively for the surgical groups) for the KOS, PCS, TUG, and SCT. The control group showed higher KOS and PCS scores and lower TUG and SCT times. Only the KOS scores remained significantly different between groups at 2 years of follow-up. Post hoc testing revealed that the bilateral group had a 10-point lower KOS score than control group (P = .003). No other significant differences were seen.

Fig. 2.

Although the bilateral and unilateral groups showed a significant increase in KOS grades from initial evaluation to 2-year follow-up (asterisk) (P < .001), a significant difference existed in the KOS values between the bilateral and the control group (asterisk) (P = .003). No differences existed between either of the surgical groups at any of the periods.

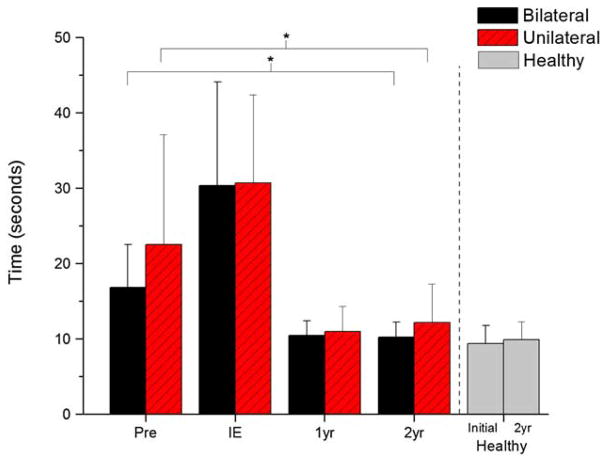

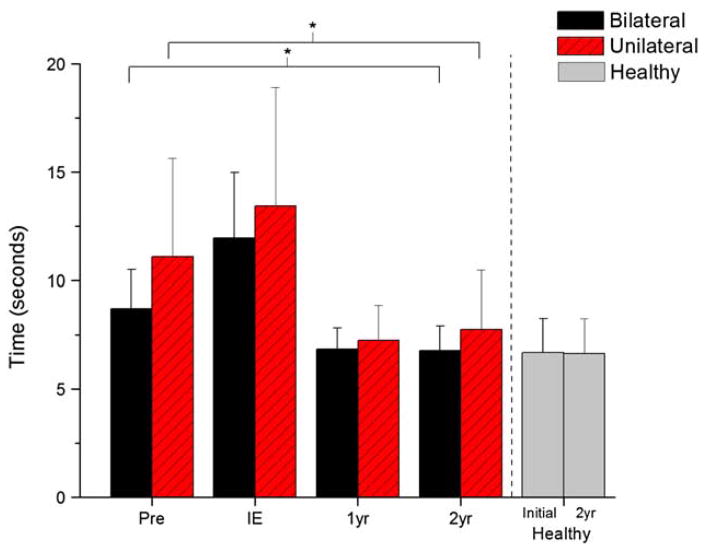

Fig. 5.

Statistically significant and clinically meaningful decreases in the time for the SCT were seen in both of the surgical groups (asterisk) (P < .001). At 2 years after the surgery, these values were not significantly different than the times noted in the control group (P = .13).

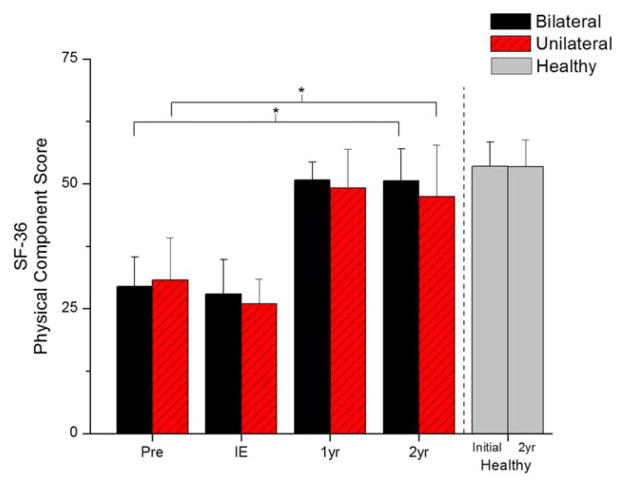

At 2 years of follow-up, the unilateral and bilateral groups showed a significant increase in KOS and PCS scores compared to preoperative values (Figs. 2–3). The bilateral group had an increase in the KOS score from 45.5% ± 14% to 87% ± 9% (P < .001) and the PCS increased from 29.5 ± 5.9 to 51.8 ± 6.1 (P < .001). The unilateral group had an initial KOS score of 47.4% ± 20%, and this increased to 91.0% ± 12% (P < .001). The PCS score in the unilateral group increased from 30.5 ± 7.6 to 47.7 ± 10.0 (P < .001). No differences were found after 2 years for the control group for KOS and PCS.

Fig. 3.

Significant increases in the PCS were seen for the bilateral and unilateral TKA groups (asterisk) (P < .001). No significant differences existed between either of the surgical groups or the control group at the 2-year follow-up.

Similar to the self-perceived measures, both surgical groups showed significant improvement in TUG and SCT times compared to preoperative times (Figs. 4–5). Preoperative mean TUG time for the bilateral group was 8.7 ± 1.8 seconds that decreased to 6.7 ± 1.3 seconds at 2-year follow-up (P = .001). For the SCT the bilateral group had a mean preoperative time of 16.8 ± 5.7 seconds that decreased to 10.0 ± 1.9 seconds at 2-year follow-up (P < .001). The unilateral group had a similar trend with an initial mean TUG time of 10.7 ± 3.9 seconds and initial SCT time of 22.7 ± 13.5 seconds. These times decreased to 7.7 ± 2.6 seconds (P = .004) and 12.0 ± 5.0 seconds (P = .001) for the TUG and SCT, respectively. No differences were found after 2 years for the TUG in the control group; however, SCT showed a statistically significant decrease of 0.5 seconds in this group (P = .022).

Fig. 4.

Persons in the bilateral and unilateral TKA groups showed a significant reduction in TUG times at the 2-year follow-up. There were no differences between any of the groups at the final follow-up (P = .20).

Discussion

We hypothesized that simultaneous bilateral TKA would provide long-term functional outcomes that were comparable to unilateral TKA. In our subject sample, we found that persons who underwent simultaneous bilateral TKA improved in both self-perceived and objective measures of function at 2 years. The improvements were similar to a matched sample of persons who underwent unilateral TKA. For the PCS, TUG, and SCT, no significant differences were found between surgical groups at the initial physical therapy evaluation, 1-year and 2-year follow-ups. This suggests that persons who undergo bilateral TKA can expect improvements in function throughout the course of recovery that are similar to those who undergo unilateral TKA. In addition, the long-term outcomes from the bilateral and unilateral group were similar to the control subjects at 2 years. With the exception of KOS scores, no differences were found between surgical and control groups after 2 years. This suggests that surgical intervention for knee OA can improve functional ability to levels comparable to healthy control subjects who have no history of lower extremity dysfunction.

In today’s managed health care system, insurance companies highlight the importance of the cost benefit of elective surgical procedures. Third party payers demand assurance that money spent on a surgical intervention will produce cost-effective results. It is often a concern of patients and medical professionals that simultaneous bilateral TKA will increase the early recovery time and subsequently increase the postsurgical rehabilitative costs to the insurance company as well as the individual. In our sample of subjects, there was no difference in the time from surgery to the time that the subjects were able to participate in outpatient physical therapy. Although this is an important statement about the cost-effectiveness of bilateral TKA, it is also an important clinical finding as early physical therapy intervention will improve the functional abilities of persons after a TKA [21,22]. Furthermore, at the initial physical therapy evaluation there was no difference between groups for any of the functional measures (Figs. 2–5). This suggests that simultaneous bilateral knee arthroplasty does not delay the early recovery of function. Persons undergoing simultaneous bilateral knee arthroplasties may be more likely to be discharged to an inpatient rehabilitation facility, whereas persons with unilateral TKA are more likely to be discharged home after surgery [12]. Although this may imply that the immediate postoperative hospital course may be more difficult with a bilateral TKA, it did not seem to affect the functional ability of subjects approximately 1 month after surgery when they presented to the outpatient physical therapy clinic. Similarly, bilateral TKA vs unilateral TKA did not affect the long-term functional recovery of the individuals.

Our long-term results agree with previous literature that suggests that unilateral TKA is a viable treatment of end-stage knee OA [23,24]. However, previous literature has neglected the long-term functional outcomes of bilateral TKA. In this study, large and clinically relevant improvements for both the bilateral and unilateral groups were seen in the self-perceived and objective measures for the 2-year recovery period. We showed bilateral TKA will improve functional scores in a fashion similar to unilateral TKA, and these scores at the 2-year follow-up are comparable to healthy controls. This was seen in the similarity between the SCT and TUG scores between the surgical groups and the control group. The PCS score for the bilateral and unilateral groups were also similar to the control group, and because the PCS is a norm-based test, the surgical groups were also very close to the national average score of 50. This is an important finding and illustrates that the surgical intervention can restore function to a level akin to the abilities of a healthy age-matched control group. Although no differences were found for the PCS, TUG, and SCT, persons in the bilateral group did have lower KOS scores at 2 years compared to the healthy controls. Although the difference between these groups was 10 percentage points, there was no significant difference between the bilateral group and the unilateral group (mean difference, 5 percentage points; P = .12) and no difference in the change scores for the bilateral and unilateral TKA groups (mean change bilateral, 41 percentage points; unilateral, 43 percentage points; P = .78). This corresponds to an increase of 91% in the bilateral TKA, a clinically relevant improvement that should not be undermined by the difference from the control group.

The mean number of outpatient physical therapy treatments was 16.5 for the bilateral group. This was not different than the mean number of treatments from a larger cohort of unilateral TKA subjects at the same therapy clinic (16.7 days). The therapy regimen between 2 groups of subjects was similar that suggests that persons with bilateral TKA do not require more physical therapy visits to achieve similar functional outcomes. This lends further support to the argument that bilateral TKA is a cost-effective surgical intervention for bilateral disease. If a person were to undergo a staged bilateral procedure separated by a period greater than a few months, they would likely require twice the amount of rehabilitation services to achieve the same outcome.

Another interesting result was that persons who underwent unilateral TKA had a significant increase in BMI and body mass, whereas persons in the bilateral TKA and control group did not (Fig. 1). This supports previous findings that refute the misconception that surgical intervention for end-stage knee OA will permit increased mobility and the potential for weight loss [25,26]. Because disease progression and decreased muscle strength on the contralateral, or non-operated side, may contribute to reduced long-term functional ability, this may be the reason only the unilateral group showed a significant increase in BMI and body mass [13]. In this group, an increase in pain or a decrease in function on the nonoperated knee may lower an individual’s ability to perform activities that would facilitate weight loss. Although no differences in functional ability were seen between groups, the measures used in this study evaluate functional ability of relatively short-term activities. It may be that persons in the unilateral group have difficulty performing sustained activity that would be most complementary to a reduction in body weight. Further studies that include functional measures related to prolonged physical activity would be required to evaluate this assumption.

In our current study, we had a relatively small sample size for our treatment groups. In both of the groups, no subjects reported or had serious postoperative complications. The results from this study should be examined in light of this fact. Complication rates may be higher in the bilateral TKA group, but in our cohort, functional outcomes were not affected by complications related to the surgery. In addition, functional outcomes after unilateral TKA may be affected by the status of the nonoperated limb. It should be noted that in our sample of patients, we did not radiologically assess disease progression in the nonoperated limb, and we cannot make assumptions about the nonoperated limb in this group. However, in light of the continued functional improvements in the unilateral group, we feel confident that our results reflect functional outcomes from a sample of patients without serious complication or severe disease progression in the nonoperated limb.

Simultaneous bilateral TKA appears to be a viable alternative to staged bilateral or unilateral TKA in the presence of bilateral disease. Persons who had simultaneous bilateral TKA show a similar recovery course as measured by self-perceived and objective clinical measures. Even early postoperative recovery at 1 month did not reveal significant differences between groups. Subjects who had both knees replaced were able to participate in outpatient physical therapy care as early as subjects who underwent a unilateral replacement. In light of these results and previous work that demonstrated a decreased cost to the health care system and to the individual, we feel that subjects medically appropriate for simultaneous bilateral TKA should be afforded this surgical option.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Leo Raisis and Dr. Alex Bodenstab for performing the total knee arthroplasties, as well as the University of Delaware Physical Therapy Clinic for providing the post-operative treatment. Funding for this study was provided by the National/Institutes of Health Grant Numbers: R01HD041055 and P20RR016458.

Funds were received from NIH (National Institutes of Health).

References

- 1.Murphy L, et al. Lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:9. doi: 10.1002/art.24021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hootman JM, Helmick CG. Projections of US prevalence of arthritis and associated activity limitations. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1. doi: 10.1002/art.21562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMahon M, Block JA. The risk of contralateral total knee arthroplasty after knee replacement for osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuben JD, et al. Cost comparison between bilateral simultaneous, staged, and unilateral total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:2. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(98)90095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horne G, Devane P, Adams K. Complications and outcomes of single-stage bilateral total knee arthroplasty. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:9. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ritter MA, Harty LD. Debate: simultaneous bilateral knee replacements: the outcomes justify its use. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004:428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritter MA, Meding JB. Bilateral simultaneous total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1987;2:3. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(87)80036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.March LM, et al. Two knees or not two knees? Patient costs and outcomes following bilateral and unilateral total knee joint replacement surgery for OA. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:5. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritter M, et al. Outcome implications for the timing of bilateral total knee arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997:345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritter MA, et al. Simultaneous bilateral, staged bilateral, and unilateral total knee arthroplasty. A survival analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:8. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200308000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Restrepo C, et al. Safety of simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:6. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lane GJ, et al. Simultaneous bilateral versus unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Outcomes analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997:345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farquhar S, Snyder-Mackler L. The Status of the Non-operated Knee is the Primary Predictor of Function 3 Years after Unilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty. CORR. 2009;467:11. (In Press) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irrgang JJ, et al. Development of a patient-reported measure of function of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:8. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199808000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marx RG, et al. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of four knee outcome scales for athletic patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:10. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fortin PR, et al. Outcomes of total hip and knee replacement: preoperative functional status predicts outcomes at six months after surgery. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:8. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199908)42:8<1722::AID-ANR22>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fortin PR, et al. Timing of total joint replacement affects clinical outcomes among patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:12. doi: 10.1002/art.10631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brazier JE, et al. Generic and condition-specific outcome measures for people with osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.9.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE, Jr, et al. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care. 1995;33(4 Suppl):AS264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up and Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:2. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bulthuis Y, et al. Cost-effectiveness of intensive exercise therapy directly following hospital discharge in patients with arthritis: results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:2. doi: 10.1002/art.23332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minns Lowe CJ, et al. Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise after knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2007;335:7624. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39311.460093.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshida Y, et al. Examining outcomes from total knee arthroplasty and the relationship between quadriceps strength and knee function over time. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2008;23:3. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NIH. NIH Consensus Statement on total knee replacement. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2003;20:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donovan J, Dingwall I, McChesney S. Weight change 1 year following total knee or hip arthroplasty. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:4. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodruff MJ, Stone MH. Comparison of weight changes after total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:1. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.9826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]