Abstract

Background

Pelvic fractures represent major injury. Women of childbearing age who have sustained pelvic fractures question whether they can have children and what type of delivery will be possible.

Questions/purposes

(1) Genitourinary and sexual dysfunction can be expected in women of child bearing age with pelvic fractures; (2) functional outcomes of women with pelvic fractures are related to fracture pattern and whether they were treated with surgery; (3) women treated nonoperatively and those treated operatively with fixation sparing the pubic symphysis can deliver children vaginally.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 71 women with pelvic fractures. Forty-one had stable fractures and 25 had unstable fractures; five radiographs could not be located to classify fractures. Forty women had surgery for their pelvic fractures.

Results

Thirty-five women (49%) had one or more genitourinary complaints; 26 women (38%) had pain with sexual intercourse. The overall SF-12 score and physical and mental health component were lower in women who had surgical fixation of their pelvic fracture. Overall SF-12 scores were similar in women who did and did not have children after their pelvic fracture. Twenty-six women had children after their pelvic fracture: 10 (38%) delivered vaginally; 16 (62%) had a cesarean section. Four (40%) of the women who delivered vaginally had surgical fixation of their fracture, including rami screws and/or sacroiliac screws.

Conclusions

Our data suggest the cesarean section rate is still more than double standard norms, but vaginal delivery after pelvic fracture, even in those treated with surgical fixation sparing the pubic symphysis, is possible.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study. See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Pelvic fractures represent major injury with long-term functional and socioeconomic effects. Associated complications can include both short- and long-term effects on the genitourinary and reproductive system [2, 11]. With women of childbearing age, pelvic trauma may have far-reaching complications. These women naturally worry about pain with sexual relations and whether or not they can have children. They wonder if their pelvic fracture affects what type of delivery will be possible. In addition, there are increasing studies reporting occurrence of posttraumatic stress and decreased functional outcomes among female trauma patients [4, 8, 16].

Pelvic ring disruption represents a spectrum of injury with some fractures treated nonoperatively, whereas others require surgical stabilization and are life-threatening injuries. A variety of stabilization techniques also exist ranging from minimally invasive percutaneous techniques [5] to fixation spanning the pubic symphysis [5, 18] and/or sacroiliac joints [5, 18]. In addition, after a pelvic fracture, women may have negative feelings about themselves, which may manifest in lower functional outcome scores [2, 11].

Even in the obstetric community, there is belief women who have had pelvic fractures cannot deliver vaginally [3, 6, 10, 18]. Many women are not even given a chance for a trial of labor once the obstetrician is aware of the history of pelvic fracture [2]. However, nonoperative treatment of these fractures or operative treatment with iliac wing fixation, external fixator, and/or ramus screws should not generally affect the pelvic proportions or mobility of the symphysis and sacroiliac joints. Given the importance of the mobility of the symphysis and sacroiliac joints during delivery, concern may be warranted if there is fixation across the pubic symphysis and possibly the sacroiliac joints. However, it is unclear whether pelvic fractures or their treatments indeed interfere with delivery.

We therefore asked whether (1) genitourinary and sexual dysfunction can be expected in women with pelvic fractures (even stable fractures treated nonoperatively); (2) functional outcomes of women with pelvic fractures can be related to fracture pattern and whether they were treated with surgery; and (3) women with pelvic fractures treated nonoperatively and those treated surgically with fixation not crossing the pubic symphysis can deliver children vaginally.

Patients and Methods

This study was a two-center study consisting of patients treated at Parkland Memorial Hospital, Dallas, TX, and the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS, between 2000 and 2007. Using trauma registries we identified 530 female patients between the ages of 16 and 45 years who were diagnosed with a pelvic fracture. All 530 patients who met our inclusion criteria were contacted by mail. They were sent a letter summarizing the study and study forms (Appendix 1) and questionnaires (Appendix 2) in a self-addressed stamped envelope. For women who had children after their pelvic fracture, once we received the release form from the patient we then sent a letter to their obstetrician asking them to fill out the data regarding all births in these patients after their pelvic fracture (Appendix 3). There were 210 envelopes returned to sender (RTS). We used an internet search service (411connect.com) to try to find a more current address and we were able to obtain responses from 14 women after we used this service. Three envelopes were returned marked as “deceased”. Overall, 196 envelopes were RTS, three patients were deceased and 260 did not respond. Seventy-one of the 530 women (13%) completed the forms. Complete responses were available for only 68 patients as three patients did not answer every question. The average age of the women at the time of their trauma was 27.8 years (range, 17–44 years). The average age of the women who were completing their forms was 33.8 years (range, 19–55 years). The women completed their forms at an average of 6 years (range, 1–9 years) after their trauma. Twenty-six women (37%) had a baby since their injury. Fifty-seven women were injured in motor vehicle collisions, three were pedestrians struck by a motor vehicle, seven were injured in a fall, and four were injured in miscellaneous occurrences (all-terrain vehicle accident; fall from a horse; tornado; and car rolled over patient). We obtained Institutional Review Board approval before beginning this study.

We classified fractures according to the Burgess et al. classification (sometimes mentioned in the literature as “Young-Burgess”) [1]. Stable fractures were lateral compression type I (LC-I) pelvic fractures and anteroposterior compression type I (APC-I) fractures. Unstable fractures were considered lateral compression II (LC-II) and III (LC-III) fractures, anteroposterior compression II (APC-II) and III (APC-III) fractures, and vertical shear (VS) and combined mechanisms (CM) pelvic fracture. We used the initial injury radiographs for the pelvic fracture classification. We were unable to locate the radiographs of five of the 71 patients and thus could not classify their injuries; they were injured in the years 2000 to 2001 and radiographs were destroyed after 7 years at the institutions. Forty-one of the remaining 66 patients had stable fractures: 40 with LC-I injuries and one patient with an APC-I injury. Twenty five patients had unstable fractures; eight patients with an LC-2 injury, seven with an LC-3 injury, four with an APC-2 injury, two with an APC-3 injury, and four with a vertical shear pelvic fracture.

We reviewed the medical records for treatment of their pelvic fracture. If the patient had surgery, details regarding the surgery and type of fixation used were recorded, including the use of unilateral/bilateral sacroiliac screws, iliac wing fixation, rami screws (unilateral or bilateral), transsymphyseal plating, and/or use of an external fixator. Surgical data were not available on five of the 71 patients secondary to the length of time from their injury and the records were destroyed after 7 years. Twenty-six of the 66 women were treated nonoperatively and 40 had surgery (Table 1). LC1 fractures represent a spectrum of injury and were classified as stable fractures although 15 LC1 fractures were treated surgically with rami screws or sacroiliac screw fixation.

Table 1.

Surgical fixation

| Main fixation type | Additional fixation | |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior pubic plating | 8 | 7 |

| Ramus screws | 10 | |

| Unilateral | 8 | 4 |

| Bilateral | 2 | 1 |

| Unilateral SI screws | 16 | 7 |

| Bilateral SI screws | 5 | 1 |

| Iliac wing fixation | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 40 | 20 |

SI = Sacroiliac.

The sample characteristics were described using descriptive measures of central tendency. We evaluated major differences between interval and categorical variables within the sample using parametric t-tests and nonparametric Mann-Whitney U and chi square tests for nominal variables. These nonparametric alternatives were used when assumptions for parametric methods were not met. SPSS Version 15.0 (Chicago, IL) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Thirty-five women (49%) had one or more genitourinary complaints (Table 2). Twenty six women (38%) had pain with sexual intercourse. The patient questionnaire results (Table 2) showed no difference between the initially classified stability of fracture and genitourinary complaints. Stability of fracture or having surgery was not a major difference in those patients with dyspareunia.

Table 2.

Questionnaire results (select answers)

| Need for CS after pelvic fracture | Yes | 12 |

| No | 56 | |

| Total | 68 | |

| Afraid to get pregnant | Yes | 20 (29%) |

| No | 48 (71%) | |

| Total | 68 | |

| Self reported urinary symptoms (positive response) N = 71 Please note some reported more than one symptom | ||

| a. Urinary tract infections | 11(16%) | |

| b. Urinary frequency | 24 (34%) | |

| c. Loss of bladder control | 22 (31%) | |

| Dyspareunia | Yes | 26 (38%) |

| No | 43 (62%) | |

| Total | 69 | |

| Interest in sexual intercourse N = 69 | Less | 31 (45%) |

| Same | 27 (39%) | |

| More | 11 (16%) | |

| Orgasm frequency N = 69 | Less | 31 (45%) |

| Same | 24(35%) | |

| More | 13 (20%) | |

| Unable to return to work after pelvic fracture N = 71 | 22 (31%) | |

| Had an unstable pelvic fracture | 7 | |

| Had surgical fixation in their pelvis | 13 | |

We found no difference between the overall health and vitality to physical or mental health components of the SF-12 scores with stable and unstable pelvic fractures and whether the patients had surgery (Table 3). The average SF-12 score was 58.5 (range, 11.36–89.55) for the patients in this population setting. We observed no differences in SF-12 scores those women who did not or did have children after their pelvic fracture (Table 4).

Table 3.

SF-12 scores: Overall and subscores in women with and without surgical fixation

| SF 12 scores and surgical fixation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | No surgery | Significance | |

| Overall | 55.76 | 62.48 | P < 0.12 |

| Physical | 3.95 | 5.00 | P < 0.01 |

| Mental | 6.08 | 7.08 | P < 0.03 |

Table 4.

Overall SF-12 scores: Women who had children versus no children after pelvic fracture

| SF 12 scores in women who had children after pelvic fracture | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Children | No children | Significance | |

| Overall | 64.30 | 55.12 | P < 0.12 |

Twenty-six women had children after their pelvic fracture. Five women had two or more children after their pelvic fracture. Ten delivered vaginally after their pelvic fracture. Four (40%) of the women who delivered vaginally had surgical fixation of their fracture, including rami screws (1) and/or sacroiliac screws (3). One woman had a vaginal birth after a previous cesarean section. In one of seven patients with a cesarean section resulting from pelvic fracture, a trial of labor was given; it was prolonged and there was concern by the obstetrician for cephalopelvic disproportion. Four patients had a cesarean section resulting from pregnancy complications (breech, twins, abruption, sexually transmitted disease). Twenty of the 26 responding obstetricians indicated they had not treated women with pelvic fracture. Six of 26 obstetricians (23%) indicated they did not believe cesarean section was always necessary after a pelvic fracture. Their decision was based on the condition of the patient and fetus, their presentation, and progression of labor (Table 5).

Table 5.

Rationale for cesarean section

| Reasons given for cesarean section (CS) | N = 16 |

|---|---|

| Transymphyseal plating | 1 |

| History of pelvic fracture | 7 |

| History of CS | 4 |

| Pregnancy complications | 4 |

Discussion

Each year in the United States, over 100,000 patients are treated for pelvic fractures with a mortality rate of 7 to 25% [5, 13]. The pelvis is a stabilizing structure of the lower extremity and trunk with major structures passing through, including genitourinary, vascular, neurologic, and gastrointestinal structures. There can be major problems in terms of functional recovery. Female patients may be concerned about participation in sexual activity and possibly future ability to bear children. In a retrospective review of women of childbearing age with pelvic fractures, we asked whether (1) genitourinary and sexual dysfunction can be expected even with stable pelvic fractures treated nonoperatively; (2) functional outcomes are related to fracture pattern and surgery; and (3) women treated nonoperatively and those treated surgically with fixation sparing the symphysis can deliver children vaginally.

We note several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study. However, this sort of study must necessarily be retrospective as it would not be feasible to follow women of childbearing age who had a pelvic fracture in anticipation of possible childbirth. Second is the low response rate of 13%. Trauma patients may be more transient in nature and loss of followup is common. On the other hand, questions regarding sexual relations, such as frequency, orgasm and pain are sensitive issues. It is possible women who received the survey chose not to respond after reading the questions and they did not want to share details of intimate relations. More than 50% of the women who responded in our study did have children after their pelvic fracture. This may lead to a selection bias in reporting the outcomes. We believe the women who did have children after pelvic fracture selectively responded to the survey, and while this does provide some desired information, there may be women who had difficulty getting pregnant who chose not to respond, and they may have a poorer functional result. Third, pelvic fractures range from nondisplaced so called “minor” fractures to vertically and rotationally unstable injuries. One wonders whether the severity and/or treatment of the fracture may affect the postinjury nature of genitourinary and sexual complaints. In a study of 233 women with pelvic fractures and major lower extremity trauma, 45% of women reported feeling less sexually attractive and 39% reported a decrease in sexual pleasure [11]. In our study, 45% of the women reported less interest in sexual intercourse and reaching orgasm less than before their fracture.

Pelvic fractures are known to affect genitourinary function. Urinary complaints were more common, especially in women with residual pelvic fracture displacement [2]. In our study, we evaluated the fracture patterns but did not record residual displacement. We found close to half (49%) of women with pelvic fractures had one or more genitourinary complaints, and this was not related to fracture pattern/stability. This topic is not well covered in the literature with only one article addressing specifically female genitourinary complaints after pelvic trauma. Copeland et al. found women were more likely to have more than one urinary complaint, finding 57 complaints in 26 subjects [2]. The overall rate of urinary complaints compared to controls in her study was 21% [2]. There were few genitourinary injuries recorded in that population and perhaps subclinical soft tissue injuries or prolonged urinary catheterization could have been the contributing factors [2]. We did not evaluate the associated soft tissue injuries or length of urinary catheter use in our patients. Overall, without direct genitourinary injuries such as bladder rupture or vaginal laceration, one would not expect a 49% rate of urinary complaints, but perhaps this is not fully evaluated or asked in the post injury followup.

There is increasing interest in the effect of trauma on functional outcomes. There are validated outcome measures used. In a study of women with major lower extremity trauma and women with pelvic fractures, the SF-36 was used and compared to age standardized norms. The patients as a group scored considerably worse in all dimensions [11]. In our study, we looked for differences in outcome related to fracture type and treatment. We did not find differences in overall scores. However, the overall SF-12 scores were higher in women who had children after a pelvic fracture. Considering that women have a higher rate of posttraumatic stress disorder and postpartum depression can occur [4, 8, 16], this result was not anticipated. There was an average of 6 years from the trauma until the patients completed the forms. Perhaps this length of time after trauma and having a child both contributed to the better overall functional outcome score.

The treatment for pelvic fractures ranges from nonoperative with full weight bearing to limited weight bearing and percutanous fixation to open reduction and internal fixation. Even the so-called stable lateral compression pelvic fracture may be considered unstable and treated operatively [7]. Thus, it is difficult to predict the type of delivery a woman may have should she get pregnant after a pelvic fracture. In one paper directly evaluating cesarean section rates of women with pelvic fractures who had children before and after their fracture, the cesarean section rate was substantially increased postinjury (14.5% preinjury versus 48% postinjury) [2]. Other authors have reported variable rates of cesarean section after pelvic fractures, ranging from 8% to 66% [10, 15, 18]. Currently, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology reports the cesarean section rate to be 31% [9, 17]. Our rate of cesarean sections in women after pelvic fracture was double the rate in the United States. The history of pelvic fracture contributed to 44% (seven of 16) cesarean sections and history of cesarean section was responsible for 25% of the cesarean sections. A trial of labor was only given in one of 11 cesarean sections. Cesarean sections expose the patient and fetus to anesthetic and surgical risk. The decision may not be based on any factor other than lack of knowledge regarding the ability to deliver vaginally after a pelvic fracture because 77% of obstetricians who completed the patient’s records indicated they had not treated patients with pelvic fractures. There may be a concern for litigation. Other factors that may contribute to increased cesarean section rates after a pelvic fracture include the question of whether pelvic disproportion exists, obstetrician training and experience, and previous results [3, 6, 9, 10, 12, 14, 15, 17, 18].

Overall, there is a paucity of data and a variety of published opinions regarding childbirth after pelvic fractures [2, 10, 14, 15, 18]. Our data suggest the cesarean section rate is more than double standard norms, but vaginal delivery after pelvic fracture, even in those treated with surgical fixation sparing the pubic symphysis, is possible. In addition, women who had children after pelvic fractures had considerably higher SF-12 overall scores. That was an unexpected, yet encouraging result. Pelvic fractures represent a serious injury for women of childbearing age. The possible genitourinary, sexual and functional outcomes along with ability to have a vaginal delivery after surgical fixation of a pelvic fracture should be discussed with patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Heidi Israel, PhD, St Louis University Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, for providing the statistics for this study.

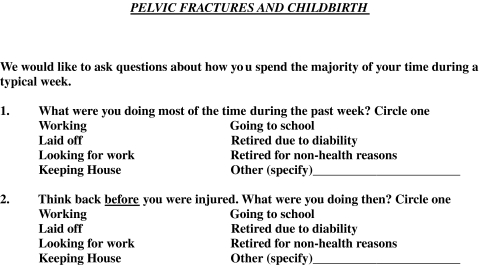

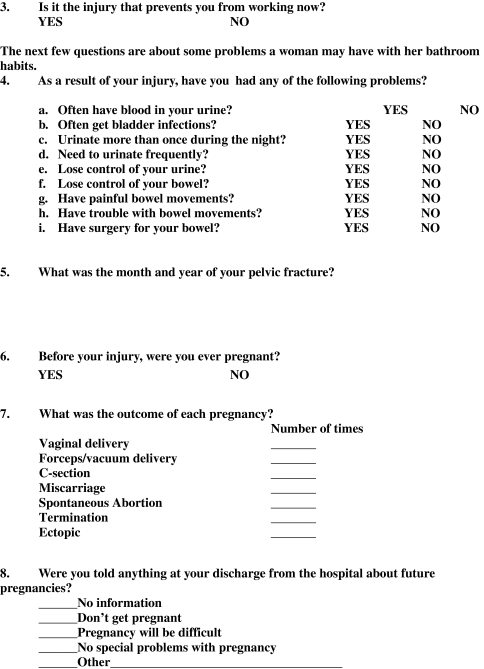

Appendix 1 Information/Consent Packet Contents

Letter Explaining Study

HIPPA Form and Consent

Consent

Release Form to Obstetrician (if patient had child after pelvic fracture)

Questionnaire (see Appendix 2)

SF 12

Appendix 2

Pelvic Fractures and Childbirth

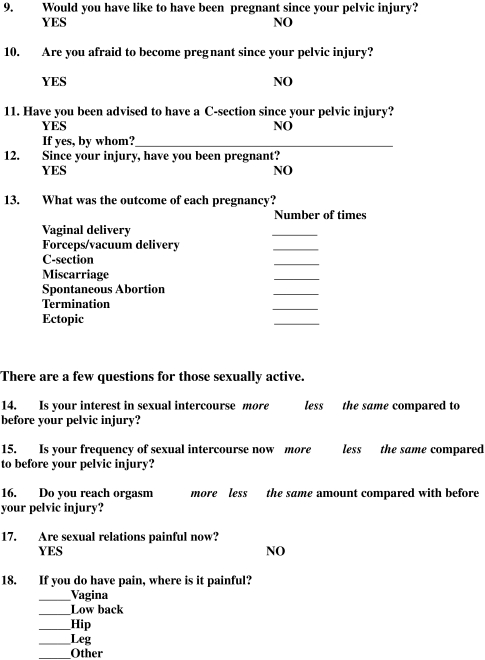

Appendix 3

Parturition and Pelvic Fractures

Footnotes

The author’s institutions (LKC, University of Texas-Southwestern Medical Center and St Louis University; JB, University of Mississippi) received research support for this study from the Foundation for Orthopaedic Trauma and the Ruth Jackson Orthopaedic Society Zimmer Research Award.

Each author certifies that her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at the University of Texas-Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA, and the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS, USA.

References

- 1.Burgess AR, Eastridge BJ, Young JW, Ellison TS, Ellison PS, Jr, Poka A, Bathon GH, Brumback RJ. Pelviv ring disruption: effective classification system and treatment protocols. J Trauma. 1990;30:848–856. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199007000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Copeland CE, Bosse MJ, McCarthy ML, MacKenzie EJ, Guzinski GM, Hash CS, Burgess AR. Effect of trauma and pelvic fracture on female genitourinary, sexual, and reproductive function. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11:73–81. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199702000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guillemette J, Fraser WD. Differences between obstetricians in caesarean section rates and the management of labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:105–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb14464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holbrook TL, Hoyt DB. The impact of major trauma: quality-of-life outcomes are worse in women than in men, independent of mechanism and injury severity. J Trauma. 2004;56:284–290. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000109758.75406.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kellam JF, Mayo K. Pelvic ring disruption. Pelvic fractures. In: Browner BD, Jupiter JJ, Levine AM, Trafton PG, eds. Skeletal Trauma. 3rd Ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2003:1063.

- 6.Krishnamurthy S, Fairlie F, Cameron AD, Walker JJ, Mackenzie JR. The role of postnatal x-ray pelvimetry after caesarean section in the management of subsequent delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98:716–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb13462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LeFaivre KA, Padelecki JR, Starr AJ. What constitutes a Young and Burgess lateral compression I (OTA 61–B2) pelvic ring disruption? A description of computed tomography-based fracture anatomy and associated injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23:16–21. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31818f8a81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lev-Weisel R, Chen R, Daphna-Tekoah S, Hod M. Past traumatic events: are they a risk factor for high-risk pregnancy, delivery complications and post-partum post-traumatic symptoms? J Womens Health. 2009;18:119–125. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacDorman MF, Menacker F, Declerq E. Cesarean births in the United States: epidemiology, trends and outcomes. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35:293–307. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madsen LV, Jensen J, Christensen ST. Parturition and pelvic fracture. Follow-up of 34 obstetric patients with a history of pelvic fracture. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1983;62:617–620. doi: 10.3109/00016348309156259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarthy ML, Mackenzie EJ, Bosse MJ, Copeland CE, Hash CS, Burgess AR. Functional status following orthopaedic trauma in young women. J Trauma. 1995;39:828–837. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199511000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulla N. Fracture of the pelvis in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1957;74:246–250. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)37068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sathy AK, Starr AJ, Smith WR, Elliot A, Agudelo J, Reinert CM, Minei JP. The effect of pelvic fracture on mortality after trauma: an analysis of 63, 000 trauma patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am; 2009;91:2803–2810. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuman W. Fractured pelvis in obstetrics (with report of cases) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1932;23:103–107. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Speer DP, Peltier LF. Pelvic fractures and pregnancy. J Trauma. 1972;12:474–480. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197206000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starr AJ, Smith WR, Frawley WH, Borer DS, Morgan SJ, Reinert CM, Mendoza-Welch M. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder after orthopaedic trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1115–1121. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B8.14240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang YT, Mello MM, Subramanian SV, Studdert DM. Relationship between malpractice litigation pressure and rates of cesarean section and vaginal birth after cesarean section. Med Care. 2009;47:234–242. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818475de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou SR. Fracture-dislocation of pelvis in the adult female: clinical analysis of 105 cases. Zhonga Wai Ke Za Zhi. 1989;27(479–481):509–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]