Abstract

Timely sensing of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is critical for the host to fight invading Gram-negative bacteria. We recently showed that apolipoprotein CI (apoCI) (apoCI1–57) avidly binds to LPS, involving an LPS-binding motif (apoCI48–54), and thereby enhances the LPS-induced inflammatory response. Our current aim was to further elucidate the structure and function relationship of apoCI with respect to its LPS-modulating characteristics and to unravel the mechanism by which apoCI enhances the biological activity of LPS. We designed and generated N- and C-terminal apoCI-derived peptides containing varying numbers of alternating cationic/hydrophobic motifs. ApoCI1–38, apoCI1–30, and apoCI35–57 were able to bind LPS, whereas apoCI1–23 and apoCI46–57 did not bind LPS. In line with their LPS-binding characteristics, apoCI1–38, apoCI1–30, and apoCI35–57 prolonged the serum residence of 125I-LPS by reducing its association with the liver. Accordingly, both apoCI1–30 and apoCI35–57 enhanced the LPS-induced TNFα response in vitro (RAW 264.7 macrophages) and in vivo (C57Bl/6 mice). Additional in vitro studies showed that the stimulating effect of apoCI on the LPS response resembles that of LPS-binding protein (LBP) and depends on CD14/ Toll-like receptor 4 signaling. We conclude that apoCI contains structural elements in both its N-terminal and C-terminal helix to bind LPS and to enhance the proinflammatory response toward LPS via a mechanism similar to LBP.

Keywords: peptide, inflammation, endotoxins, TNFα, mice

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a major constituent of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. LPS molecules can be released from the outer membrane upon death or rapid growth and signal the presence of these bacteria in the circulation via activation of the myeloid differentiation protein-2 (MD2)-Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-complex on monocytes/macrophages and endothelial cells (1–6). Timely sensing of LPS by inflammatory cells to stimulate the inflammatory response toward LPS and bacteria is crucial for activation of the host defense system to fight Gram-negative infection (7). If the initial antibacterial inflammatory response is inadequate or too late, uncontrolled bacterial growth will occur with excessive release of LPS into the circulation. This will lead to an exaggerated systemic host response with respect to excessive production of inflammatory mediators, which can ultimately result in the serious and life-threatening symptoms of septic shock (8, 9).

Apolipoprotein CI (apoCI) is the smallest identified apolipoprotein (57 amino acids) and is unusually rich in Lys residues. ApoCI has classically been recognized as an inhibiting factor for lipoprotein clearance by affecting LPL-mediated processing (10, 11) and subsequent receptor-mediated uptake of lipoproteins by the liver (12, 13). ApoCI contains two amphipathic α-helices (apoCI7–29 and apoCI38–52) that are separated by a flexible linker (apoCI30–37), with no substantial intramolecular interactions (Fig. 1). By virtue of these properties, apoCI has a boomerang shape similar to the LPS-binding protein bactericidal/permeability increasing protein (BPI) (14, 15), albeit that apoCI (57 amino acids) is smaller than BPI (456 amino acids).

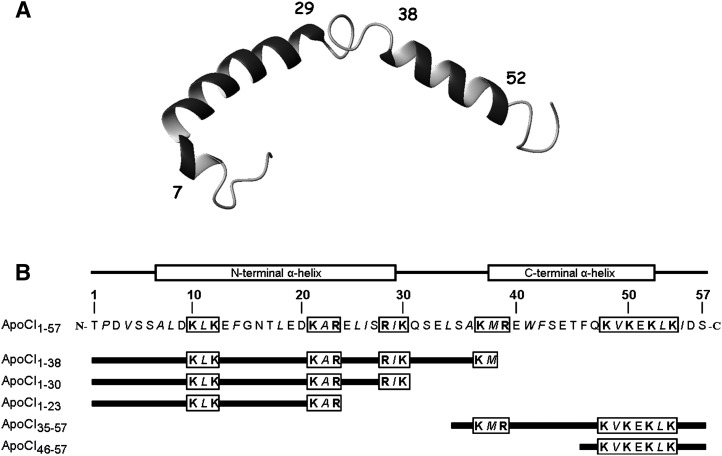

Fig. 1.

Peptide sequences of apoCI1–57 and apoCI-derived peptides. The three-dimensional structure of apoCI (A) and the primary peptide sequences (B) are shown. Residues in boldface represent basic amino acids and residues in italics represent hydrophobic residues. The previously identified LPS-binding motif (residues 48–54) and the alternating cationic/hydrophobic motifs (residues 10–12, 21–23, 28–30, and 37–39) are boxed.

ApoCI has been demonstrated to act as a negative acute-phase protein after LPS administration and during bacterial sepsis (16–18), suggestive of a role of apoCI in inflammation and sepsis. Indeed, we recently showed that apoCI strongly binds to LPS, thereby prolonging the residence time of LPS in the circulation (19). In addition, apoCI stimulated the LPS-induced production of TNFα by macrophages in vitro and in mice in vivo. By enhancing the biological response toward LPS and Gram-negative bacteria, apoCI improved the antibacterial attack, reduced bacterial outgrowth, and protected against intrapulmonal Klebsiella pneumoniae-induced fatal sepsis (19). Moreover, by enhancing the systemic inflammatory state, apoCI aggravated LPS-induced atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic apoE-deficient mice (20). We were able to extrapolate these findings to humans by showing that plasma apoCI levels positively correlate with an enhanced inflammatory response during endotoxemia (21) and with increased infection-related survival (17, 22).

We previously noted that the Lys-rich KVKEKLK motif (apoCI48–54) is highly homologous to the motifs in the proposed LPS-binding regions of the LPS-binding proteins Limulus anti-LPS factor (LALF) (LALF43-49; KWKYKGK) (23) and cationic antimicrobial peptide-18 (CAP-18) (CAP18117–123; KIKEKLK) (24) (Table 1). In fact, we have demonstrated that replacement of the Lys residues within this motif by Ala residues (i.e., AVAEALA), which neutralizes positive charges without changing the protein structure, decreased the binding to LPS and partly reduced the ability of apoCI to stimulate the LPS-induced TNFα response (19). However, in addition to the KVKEKLK motif, apoCI contains a number of alternating cationic/hydrophobic motifs throughout its structure. These motifs are also present in the proposed LPS-binding regions of other LPS-binding proteins, such as BPI, LPS-binding protein (LBP) (25), lactoferrin (Lf) (26), apoE (27), and MD2 (3) (Table 1). Similar to the previously identified LPS-binding motif of apoCI, these alternating cationic/hydrophobic motifs within apoCI are highly conserved during evolution (28) and may well be involved in the LPS-binding properties of apoCI.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the amino acid sequence of apoCI with those of proposed LPS-binding regions of several LPS-binding proteins

| LPS-binding proteins (amino acids) | Amino Acid Sequencea | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| BPI (85–100) | N I K I S G K W K A Q K R F L K M | Little et al. (37) |

| LBP (84–99) | S I R V Q G R W K V R K S F F K L | Taylor et al. (25) |

| Lf (28–34) | R K V R G P P | Elass-Rochard et al. (26) |

| ApoE (133–149)b | L R V R L A S H L R K L R K R L L | Lynch et al. (27) |

| MD2 (119–-132) | F S F K G I K F S K G K Y K | Mancek et al. (3) |

| CAP-18 (106–137) | G L R K R L R K F R N K IK E K LK K I G Q K I Q G L L P K L A | Larrick et al. (24) |

| LALF (32–50) | H Y R I K P T F R R L K WK Y K GK F | Hoes et al. (23) |

| ApoCI (1–30) | T P D V S S A L D K L K E F G N T L E D K A R E L I S R I K | |

| ApoCI (31–57) | Q S E L S A K M R E W F S E T F Q K V K E KL K I D S |

Modified from De Haas et al. (34).

Boldface residues represent basic amino acids; italic residues represent hydrophobic amino acids; underlined amino acids represent a comparable amino acid region.

The receptor-binding domain of apoE has not yet been described as a LPS-binding domain.

In this study we aimed at analyzing the structure and function relationship of apoCI with respect to binding of LPS and modulating the response to LPS. In addition, we aimed at unraveling the mechanism by which apoCI enhances the LPS-induced inflammatory response. We designed and generated an array of N- and C-terminal apoCI-derived peptides containing the LPS-binding motif and/or a varying number of highly conserved alternating cationic/hydrophobic motifs. We demonstrate that peptides containing either the full N-terminal helix or the full C-terminal helix can bind LPS and enhance the inflammatory response toward LPS, albeit with reduced efficiency as compared with full-length apoCI. Furthermore, we show that apoCI stimulates the LPS-induced proinflammatory response via an LBP-like mechanism dependent on functional CD14/TLR4 signaling. We anticipate that in addition to the previously identified LPS-binding motif, the highly conserved alternating cationic/hydrophobic motifs present throughout the apoCI sequence participate in the binding to LPS and enhancement of the biological response to LPS via a mechanism similar to LBP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

C57Bl/6 mice (own breeding) and TLR4-mutant (C3H/HeJ) and wild-type TLR4-expressing (C3H/HeN) mice from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) were housed at the breeding facility of TNO-Quality of Life in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment and were fed ad libitum with regular chow (Ssniff, Soest, Germany). All experiments were approved by the animal ethics committee of TNO or the Leiden University Medical Center. Experiments were conducted in male mice at 10–12 weeks of age.

Synthesis of apoCI-derived peptides

The synthesis of human apoCI-derived peptides was carried out by the Peptide Synthesis Facility of the Department of Immunohematology and Blood Transfusion at the Leiden University Medical Center (Leiden, The Netherlands) by solid phase peptide synthesis on a TentagelS-AC (Rap, Tübingen, Germany) using 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl/t-Bu chemistry, benzotriazole-1-yl-oxy-tris-pyrrolidino-phosphonium hexafluorophosphate/N-methylmorpholine for activation, and 20% piperidine in N-methylpyrrolidone for fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl removal (29). The peptides were cleaved from the resin, deprotected with trifluoroacetic acid/water, and purified on Vydac C18. The purified peptides were analyzed by reversed phase-HPLC and their molecular masses were confirmed by MALDI-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (purity >95%). Synthesized full-length human apoCI (apoCI1–57; purity >95%) was obtained from Protein Chemistry Technology Center (UTSouthwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX).

Radiolabeling of LPS

Salmonella Minnesota Re595 LPS (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) was radiolabeled as described (30). Briefly, 1 mg of LPS was incubated with 4.6 mg methyl 4-hydroxybenzimidate hydrochloride (Fluka Chemie, Buchs, Switzerland) in 1 ml of 50 mM borate buffer (pH 8.5) for 18 h. After dialysis against PBS, 0.5 ml of the derivatized product was radiolabeled using 10 µL of 4 mg/ml chloramine T (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 10 µL (0.25 mCi) Na125I (Amersham, Little Chalfont, UK). The reaction was stopped with 10 µL of 4 mg/ml NaS2O4, and the radioiodinated product was dialyzed extensively against PBS (pH 7.4). Prior to experiments, the 125I-LPS was sonicated three times for 30 s, with 1 min intervals on ice in between, using a Soniprep 150 (MSE Scientific Instruments, Crawley, UK) at 10 µm output. The quality of the 125I-LPS was routinely checked by agarose gel electrophoresis. The specific activity of 125I-LPS was ∼1.0 × 103 cpm/ng.

Agarose gel electrophoresis

125I-LPS (150 ng) was incubated (30 min, 37°C) in the absence or presence of apoCI-derived peptides or apoCI1–57 at the indicated molar ratios. Aliquots of incubation mixtures were subjected to electrophoresis in 0.75% (w/v) agarose gels at pH 8.8 using 70 mM Tris-HCl, 80 mM hippuric acid, 0.6 mM EDTA, and 260 mM NaOH buffer. Bromophenol blue (Merck) served as a front marker. For detection of 125I-LPS, gels were dried overnight at 65°C, exposed to a phosphorimaging plate (BAS-MS2040; Fuji Photo Film, Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), and radioactivity was detected on a phosphor imaging analyzer (Fujix BAS-1000; Fuji Photo Film Co. Ltd.).

Serum residence and liver association of 125I-LPS

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of domitor (0.5 mg/kg; Pfizer, New York, NY), dormicum (5 mg/kg; Roche Netherlands, Mijdrecht, The Netherlands), and fentanyl (0.05 mg/kg; Janssen-Cilag B.V., Tilburg, The Netherlands) and the abdomens were opened. 125I-LPS (10 µg/kg), preincubated (30 min 37°C) with or without apoCI-derived peptides, full-length apoCI1–57, or BSA at the indicated molar ratios, was injected via the vena cava inferior. Thirty minutes after injection, the serum residence and the liver association of 125I-LPS were determined. Blood samples (<50 µL) were taken from the vena cava inferior and allowed to clot for 30 min. The samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 7,000 rpm, and 20 µL serum samples were counted for 125I-radioactivity. The total amount of radioactivity in the serum was calculated using the equation: serum volume (ml) = 0.04706 × body weight (g) (31). At the same time, liver lobules were tied off, excised, weighed, and counted for radioactivity. Mice were killed and the remainder of the liver was excised and weighed. Uptake of 125I-LPS by the liver was corrected for the radioactivity in the serum assumed to be present in the liver (84.7 µL serum/g wet weight) (32).

Challenge of macrophages with LPS

RAW 264.7 cells, a murine macrophage cell line, were seeded into 24-well plates (1 × 106 cells/well) or 96-well plates (60 × 103 cells/well) and cultured overnight at 37°C in DMEM, 10% FBS, 1% pen/strep. Cells were washed with DMEM and incubated with LPS (1 ng/ml) that was preincubated (30 min 37°C) with or without apoCI-derived peptides, apoCI1–57, soluble CD14 (sCD14), or LBP (both from Biometec, Greifswald, Germany) in DMEM supplemented with 0.01% human serum albumin (4 h at 37°C). As controls, cells were incubated with apoCI-derived peptides or apoCI1–57 alone at the highest concentration used in combination with LPS. Where indicated, cells were preincubated with apoCI1–57 (0.05 and 5 µg/ml), anti-CD14 antibody, or isotype control monoclonal antibody (10 µg/ml; Biometec) for 30 min at 37°C, washed, and subsequently stimulated with LPS. The medium was collected, and TNFα was determined in the medium using the commercially available mouse TNFα-specific OptEIATM ELISA (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Likewise, thioglycollate-elicited TLR4-mutant (C3H/HeJ) and wild-type TLR4-expressing (C3H/HeN) peritoneal macrophages from 12-week-old mice were seeded into 24-well plates (0.6 × 106 cells/well) and cultured as described above. Cells were washed, incubated with LPS preincubated with or without apoCI1–57 (10-fold molar excess), and TNFα was determined in the medium.

Challenge of mice with LPS

Mice were injected intravenously with LPS (25 µg/kg) preincubated (30 min at 37°C) without or with apoCI-derived peptides or apoCI1–57, at a 60-fold and 5-fold molar excess of peptide, respectively, in saline containing 0.1% (w/v) BSA. Just after injection (t0) and at the indicated times, blood samples were taken from the tail vein and stored on ice. Samples were centrifuged (4 min at 14,000 rpm), and TNFα levels were determined in the plasma using the commercially available mouse TNFα module set BMS607MST (Bender MedSystems, San Bruno, CA).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Design of apoCI-derived peptides

To determine the structure and function relationship of apoCI with respect to binding of LPS and modulation of the in vivo behavior of LPS, we designed and generated five peptides derived from human apoCI. Three peptides contain the full N-terminal α-helix (i.e., apoCI1–38, apoCI1–30) or a part thereof (apoCI1–23), and two peptides contain the full C-terminal α-helix (i.e., apoCI35–57) or a part thereof (apoCI46–57) (Fig. 1B). In addition to length, the N-terminal peptides differ from each other by the number of cationic/hydrophobic triads (residues 10–12, 21–23, and 28–30). Both C-terminal peptides contain the previously identified LPS-binding motif (residues 48–54) and differ by the presence of one cationic/hydrophobic triad (residues 37–39).

Effect of apoCI-derived peptides on the electrophoretic mobility of 125I-LPS

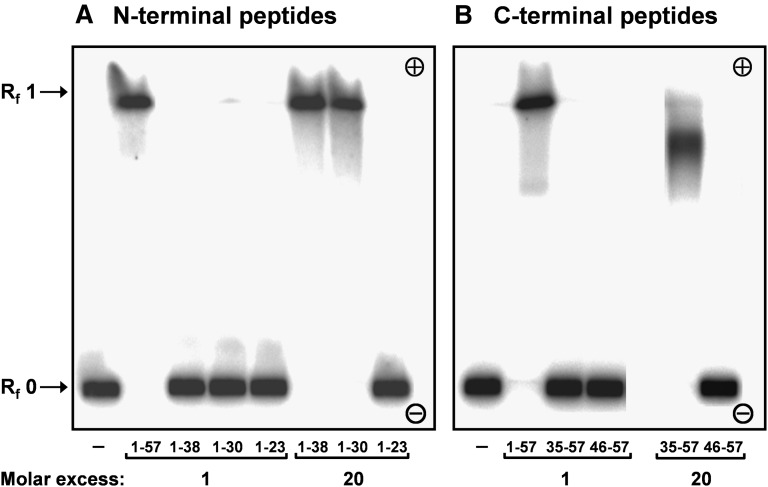

To investigate the LPS-deaggregating properties of the apoCI-derived peptides in vitro, we incubated the peptides with 125I-LPS and examined the electrophoretic mobility of the resulting radioactive complexes on agarose gel (Fig. 2). Whereas micellar 125I-LPS alone did not migrate (Rf = 0), incubation of 125I-LPS with full-length apoCI (apoCI1–57) at a 1:1 molar ratio resulted in a shift of all 125I-LPS toward the front of the gel (Rf = 0.95), confirming our previous findings (19). ApoCI1–38, apoCI1–30, and apoCI35–57 showed reduced efficiency to deaggregate 125I-LPS compared with apoCI1–57. These peptides did not deaggregate 125I-LPS at a 1:1 molar ratio but were effective at a 1:20 molar ratio. ApoCI1–23 and apoCI46–57 did not deaggregate 125I-LPS at a 1:20 molar ratio (Fig. 2) nor at a 1:60 molar ratio (not shown).

Fig. 2.

Effect of apoCI-derived peptides on the electrophoretic mobility of 125I-LPS. 125I-LPS (20 ng) was incubated without or with apoCI-peptides derived from the N-terminal helix (A) or the C-terminal helix (B) at 1:1 and 1:20 molar ratios. As a positive control, 125I-LPS was incubated with apoCI1–57 at a 1:1 molar ratio. Aliquots of the incubation mixtures (approximately 1 × 105 cpm) were subjected to electrophoresis in an 0.75% (w/v) agarose gel at pH 8.8. The resulting gel was dried and assayed for radioactivity by autoradiography.

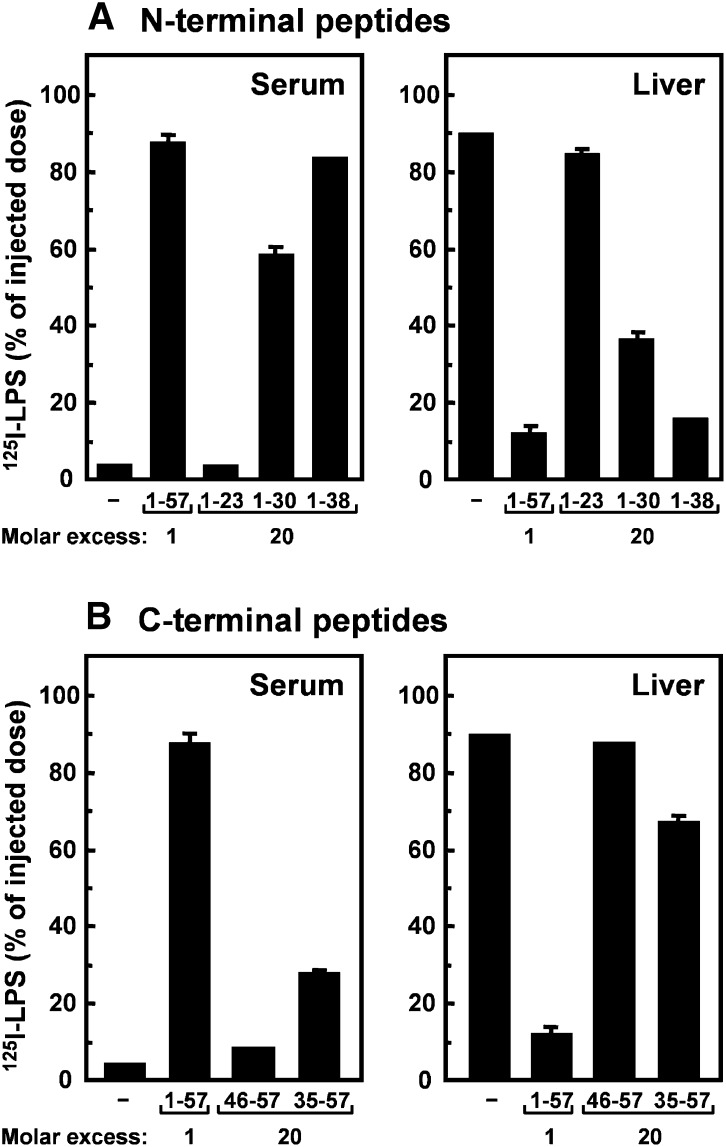

Effect of apoCI-derived peptides on the serum residence and liver association of 125I-LPS

To examine whether the LPS-deaggregating characteristics of the various peptides would be reflected in their ability to modulate the kinetics of LPS in vivo, 125I-LPS was incubated with the peptides and intravenously injected into C57Bl/6 mice (Fig. 3). 125I-LPS alone was rapidly cleared from serum and ∼90% of the injected dose associated with the liver. ApoCI1–57 almost completely prevented the serum clearance and liver association of 125I-LPS at a 1:1 molar ratio, which is in line with our previous observations (19). The N-terminal peptides apoCI1–30 and apoCI1-38 also caused a substantial increase in the serum residence of 125I-LPS and a concomitant decrease in the liver association at a 20-fold molar excess, whereas apoCI1–23 was ineffective (Fig. 3A). Both C-terminal peptides contain the previously identified LPS-binding motif but were less efficient with respect to modulating the kinetics of 125I-LPS compared with the N-terminal peptides (Fig. 3B). At a 20-fold molar excess, apoCI35–57 showed a modest increase of the serum residence and decrease of the liver association of 125I-LPS, whereas apoCI46–57 was ineffective.

Fig. 3.

Effect of apoCI-derived peptides on the serum residence and liver association of 125I-LPS in vivo. 125I-LPS (10 µg/kg) was incubated (30 min at 37°C) without or with a 20-fold molar excess of apoCI-derived peptides of the N-terminal helix (A) or of the C-terminal helix (B). The mixtures were injected via the vena cava inferior into anesthetized C57Bl/6 mice, and the serum residence (left panels) and liver association (right panels) of 125I-LPS were determined at 30 min after injection. As a positive control, 125I-LPS was incubated with apoCI1–57 in a 1:1 molar ratio. Data are expressed as percentage of injected dose ± SD (n = 2–3).

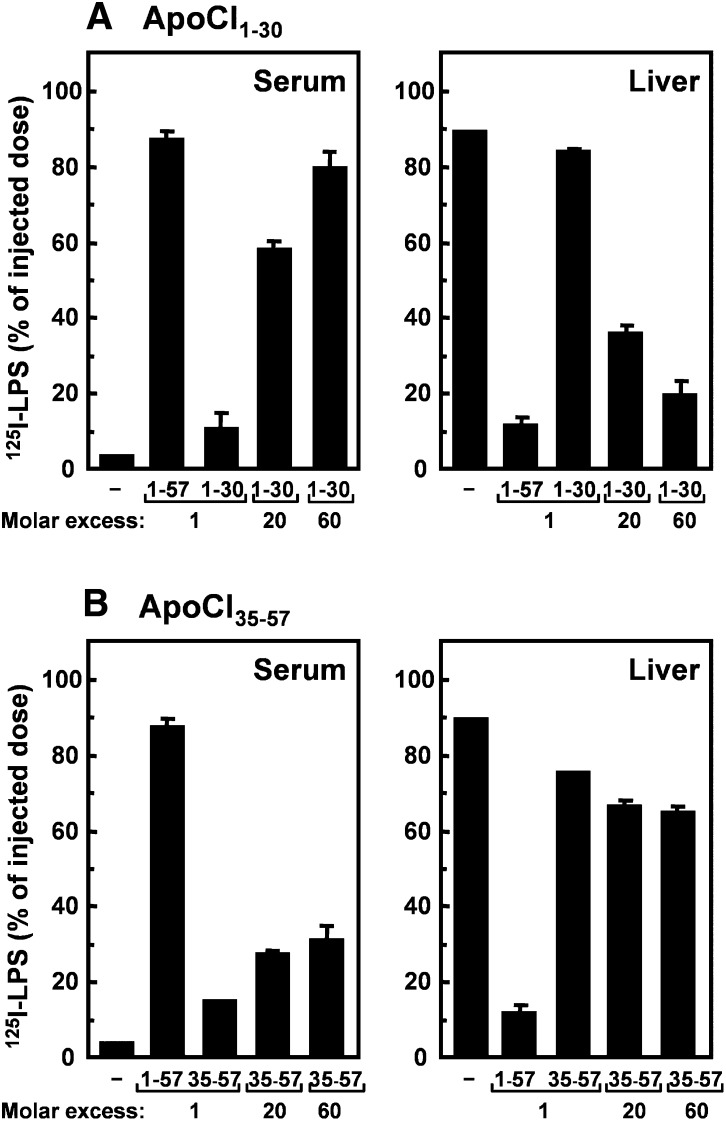

The dose dependency of the effect of apoCI1–30 (containing the full N-terminal helix) and apoCI35–57 (containing the full C-terminal helix) to modulate the kinetics of LPS was investigated in more detail (Fig. 4). ApoCI1–30 had approximately the same effect as full-length apoCI1–57 at a 60-fold higher ratio (Fig. 4A). In contrast, at this 60-fold molar excess, apoCI35–57 was still approximately 3-fold less active than apoCI1–57 (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Dose-dependent effects of peptides containing the full N-terminal helix (apoCI1–30) and full C-terminal helix (apoCI35–57) on the serum residence and liver association of 125I-LPS. 125I-LPS (10 µg/kg) was incubated (30 min at 37°C) without or with apoCI1–30 (A) or apoCI35–57 (B) at the indicated molar ratios. The mixtures were injected via the vena cava inferior into anesthetized C57Bl/6 mice, and the serum residence (left panels) and liver association (right panels) of 125I-LPS were determined at 30 min after injection. As a positive control, 125I-LPS was incubated with apoCI1–57 in a 1:1 molar ratio. Data are expressed as percentage of injected dose ± SD (n = 2–3).

Taken together, it appears that the effects of these various apoCI-derived peptides on the in vivo kinetics of 125I-LPS indeed reflect their relative LPS-deaggregating properties (Fig. 2). Importantly, both the N- and C-terminal helix contains structural components to deaggregate LPS and modulate the kinetic behavior of LPS in vivo.

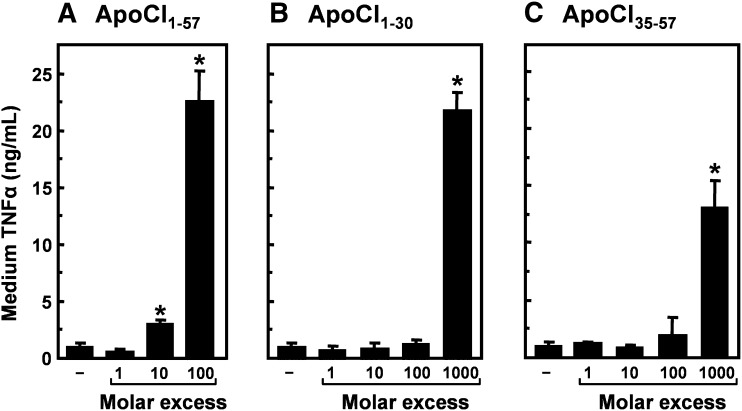

Effect of apoCI-derived peptides on the LPS-induced TNFα response in vitro

We previously showed that full-length apoCI1–57 increases the LPS-induced TNFα response both in vitro and in vivo (19). Therefore, we first determined the ability of the peptides to increase the LPS-induced TNFα response in murine RAW 264.7 macrophages compared with apoCI1–57 (Fig. 5). Incubation of macrophages with the peptides only did not result in detectable TNFα secretion in the medium (not shown). ApoCI1–57 enhanced the LPS-induced TNFα response approximately 3-fold and 24-fold at a 10-fold and 100-fold molar excess, respectively (Fig. 5A), in line with our previous observations (19). Preincubation of macrophages with 0.05 and 5 µg/ml apoCI1–57 (comparable with a 100-fold and 10,000-fold molar excess, respectively) had no effect on the LPS-induced TNFα response (not shown). Both apoCI1–30 (Fig. 5B) and apoCI35–57 (Fig. 5C) also increased the LPS-induced TNFα response. However, approximately 10-fold more peptide was required to achieve the level of stimulation as observed with apoCI1–57. ApoCI1–30 was more effective than apoCI35–57, in line with its more pronounced effect on deaggregation of LPS and modulation of the in vivo behavior of LPS.

Fig. 5.

Effect of peptides containing the full N-terminal helix (apoCI1–30) and full C-terminal helix (apoCI35–57) on the LPS-induced TNFα response in vitro. RAW 264.7 cells were incubated (4 h at 37°C) in DMEM supplemented with 0.01% human serum albumin with LPS (1 ng/ml) that was preincubated (30 min at 37°C) without or with apoCI1–57 (A), apoCI1–30 (B), or apoCI35–57 (C) at the indicated molar ratios. TNFα was determined in the medium by ELISA. Data are expressed as mean TNFα concentration ± SD (n = 3–4). *P < 0.05 compared with LPS alone.

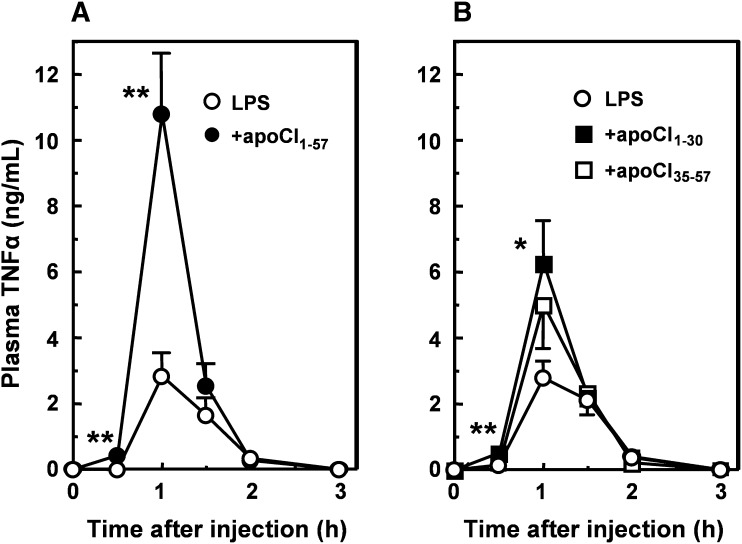

Effect of apoCI-derived peptides on the LPS-induced TNFα response in vivo

Subsequently, we determined the ability of the peptides to increase the TNFα response after intravenous injection of LPS in C57Bl/6 mice in vivo. At a 5-fold molar excess, apoCI1–57 enhanced the LPS-induced plasma TNFα levels 3.8-fold at 1 h after injection (Fig. 6A). Similarly to the in vitro macrophage stimulation studies, both apoCI1–30 and apoCI35–57 enhanced the LPS-induced TNFα response, albeit with reduced efficiency compared with apoCI1–57. At a 60-fold molar excess, the LPS-induced TNFα response was increased by apoCI1–30 (2.3-fold) and tended to be increased by apoCI35–57 (1.8-fold).

Fig. 6.

Effect of peptides containing the full N-terminal helix (apoCI1–30) and full C-terminal helix (apoCI35–57) on the LPS-induced TNFα response in vivo. LPS (25 µg/kg) incubated (30 min at 37°C) without (white circles) or with (black circles) a 5-fold molar excess of apoCI1–57 (A), or a 60-fold molar excess of apoCI1–30 (black squares) or apoCI35–57 (white squares) (B), were injected intravenously into C57Bl/6 mice. At the indicated time points, blood samples were taken and TNFα levels were determined in plasma by ELISA. Values are means ± SEM (n = 6). Statistical differences were assessed compared with LPS alone. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Collectively, our findings indicate that both the N- and C-terminal helix contain structural components able to deaggregate LPS, modulate the in vivo behavior of LPS, and enhance the LPS-induced TNFα response in vitro and in vivo.

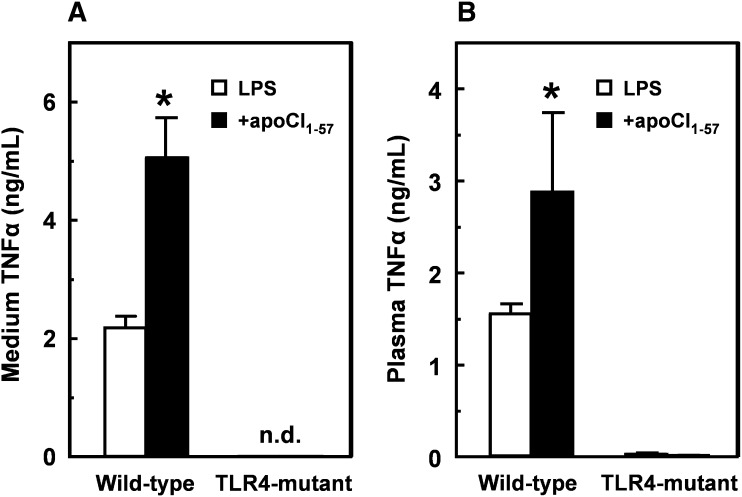

Role of TLR4 in the stimulating effect of apoCI on the LPS-induced TNFα response in vitro and in vivo

We evaluated whether apoCI and the apoCI-derived peptides augment the LPS-induced TNFα response via activation of TLR4, the signaling receptor of LPS. We stimulated peritoneal macrophages isolated from TLR4-mutant (C3H/HeJ) and wild-type TLR4-expressing (C3H/HeN) mice with LPS alone or in the presence of apoCI1–57 (Fig. 7A). In wild-type macrophages, a 10-fold molar excess of apoCI1–57 enhanced the LPS-induced TNFα response approximately 2-fold compared with LPS alone, which is comparable to the results obtained with RAW 264.7 macrophages (Fig. 5A). However, LPS without or with apoCI1–57 did not induce a detectable TNFα response in the TLR4-mutant macrophages. Similar findings were observed with apoCI1–30 and apoCI35–57 (not shown). Likewise, a 5-fold molar excess of apoCI1–57 augmented the LPS-induced TNFα response approximately 2-fold in wild-type mice, confirming our findings in C57Bl/6 mice (Fig. 6A), but LPS without or with apoCI1–57 failed to induce a TNFα response in TLR4-mutant mice (Fig. 7B). Taken together, these findings indicate that the stimulating effect of apoCI on the LPS-induced TNFα response depends on TLR4 signaling.

Fig. 7.

Role of TLR4 in the stimulating effect of apoCI on the LPS-induced TNFα response in vitro and in vivo. A: Peritoneal macrophages of TLR4-mutant (C3H/HeJ) and wild-type TLR4-expressing (C3H/HeN) mice were isolated and incubated in DMEM supplemented with 0.01% human serum albumin (4 h at 37°C) with LPS (1 ng/ml) that was preincubated (30 min 37°C) without (white bars) or with (black bars) a 10-fold molar excess of apoCI1–57. TNFα was determined in the medium by ELISA. B: LPS (25 µg/kg) incubated (30 min at 37°C) without (white bars) or with (black bars) a 5-fold molar excess of apoCI1–57 was injected intravenously into TLR4- mutant (C3H/HeJ) and wild-type TLR4-expressing (C3H/HeN) mice. After 60 min, blood samples were taken and TNFα levels were determined in plasma by ELISA. Values are means ± SD (n = 4) (A) and means ± SEM (n = 3) (B). Statistical differences were assessed compared with LPS alone. *P < 0.05.

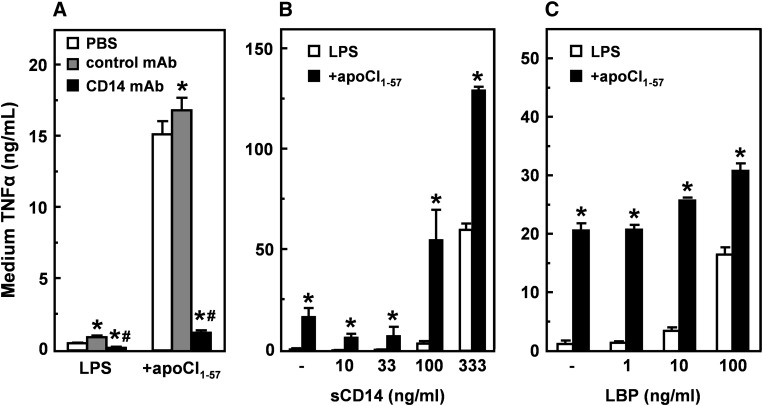

Role of CD14 in the stimulating effect of apoCI on the LPS-induced TNFα response in vitro

Finally, we studied the role of CD14 in the apoCI-mediated enhanced LPS-induced inflammatory response by blocking cell surface-bound CD14 using a CD14-specific antibody and by addition of sCD14. We preincubated RAW 264.7 macrophages with anti-CD14 antibody, followed by stimulation with LPS alone or in the presence of apoCI1–57 (Fig. 8A). Blocking CD14 almost completely inhibited the stimulating effect of apoCI on the LPS-induced TNFα response (up to 93%), while an isotype control antibody did not block the enhancing effect of apoCI1–57. In line with this finding, the addition of increasing concentrations of sCD14 to a fixed concentration of apoCI (100-fold molar excess over LPS) strongly augmented the apoCI-mediated enhanced LPS-induced TNFα response (Fig. 8B). In fact, whereas addition of apoCI1–57 alone induced LPS-induced TNFα levels up to 16.8 ± 4.4 ng/ml and sCD14 alone up to 60.2 ± 3.2 ng/ml, the combination showed a synergistic increase up to 129.5 ± 1.9 ng/ml. Collectively, these findings indicate that the stimulating effect of apoCI on the LPS-induced TNFα response thus depends on functional CD14.

Fig. 8.

Role of CD14 and LBP in the stimulating effect of apoCI on the LPS-induced TNFα response in vitro. A: RAW 264.7 cells were preincubated (30 min at 37°C) in DMEM supplemented with 0.01% human serum albumin and vehicle (white bars), isotype control antibody (gray bars), or anti-CD14 antibody (black bars), washed, and subsequently incubated (4 h at 37°C), in DMEM supplemented with 0.01% human serum albumin, with LPS (1 ng/ml) that was preincubated (30 min at 37°C) without or with a 100-fold molar excess of apoCI1–57. TNFα was determined in the medium by ELISA. B, C: RAW 264.7 cells were incubated (4 h at 37°C), in DMEM supplemented with 0.01% human serum albumin, with LPS (1 ng/ml) that was preincubated (30 min at 37°C) without or with a 100-fold molar excess of apoCI1–57 in the presence of soluble CD14 (sCD14) (B) or LBP (C). TNFα was determined in the medium by ELISA. Data are expressed as mean TNFα concentration ± SD (n = 3–4). *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle (A) or LPS alone (B, C); #P < 0.05 compared with control antibody.

Because LBP is known to bind LPS and subsequently present it to CD14, we studied the interaction between apoCI and LBP in relation to the LPS-induced inflammatory response (Fig. 8C). As expected, LBP alone dose dependently increased the LPS-induced TNFα response up to 16.5 ± 1.2 ng/ml, which is comparable to apoCI1–57 (20.2 ± 1.2 ng/ml). However, the combination of apoCI1–57 with LBP at most additively stimulated the LPS-induced TNFα response up to only 30.8 ± 1.3 ng/ml. Together, these findings indicate that apoCI does not interact with LBP but suggest that apoCI augments the LPS-induced inflammatory response via a similar mechanism as LBP does, by presenting the LPS to CD14, which ultimately transfers the LPS to the MD2/TLR4 complex.

DISCUSSION

We recently identified apoCI as an LPS-binding protein, with an apparent LPS-binding motif in its C-terminal helix, that acts as a biological enhancer of the proinflammatory response toward LPS (19). Because apoCI contains several highly conserved alternating cationic/hydrophobic motifs throughout its structure that may cooperate in LPS binding, we further investigated the structure and function relationship of apoCI with respect to its ability to bind LPS, to modulate the in vivo behavior of LPS, and to stimulate the proinflammatory response to LPS. In addition, we studied the mechanism by which apoCI enhances the LPS-induced inflammatory response. We designed and generated an array of N- and C-terminal apoCI-derived peptides containing the apparent LPS-binding motif and/or varying numbers of the cationic/hydrophobic motifs. We demonstrate that apoCI contains additional structural elements, in addition to the LPS-binding motif, that enable it to bind LPS and enhance the CD14/TLR4-dependent inflammatory response toward LPS via a mechanism similar to LBP.

Our previous studies showed that the binding of apoCI to LPS was largely mediated by a Lys-rich LPS-binding motif in the C terminus of apoCI (KVKEKLK; residues 48–54), which is highly homologous to the LPS-binding motif of LALF (23) and CAP-18 (24). Replacement of the Lys residues by Ala within this motif did decrease the ability of apoCI to bind LPS (19), but the binding to LPS was not abrogated completely. The mutant peptide was still able to modulate the in vivo kinetics of LPS to some extent (19), which indicated that apoCI should contain additional elements that cooperate in LPS binding. We now demonstrated that apoCI1–30, apoCI1-38, and apoCI35–57 all deaggregated LPS, prevented the uptake of LPS by the liver, prolonged the residence time of LPS in the serum, and enhanced the LPS-induced TNFα response. These findings indicate that both the N- and C-terminal helix contain additional structural elements that can deaggregate LPS and enhance the inflammatory response toward LPS.

To evaluate whether these apoCI-derived peptides were able to bind LPS, we determined the ability of the peptides to alter the electrophoretic mobility of 125I-LPS. Although we clearly showed that apoCI1–30, apoCI1-38, and apoCI35–57 deaggregated LPS, we were unable to show colocalization of the peptides with 125I-LPS, because the binding affinity of the detecting anti-apoCI antibody was abrogated upon any truncation of full-length apoCI. However, because we previously showed that full-length apoCI firmly bound LPS and colocalized with LPS (19), it is very likely that the LPS-deaggregation potential of the various apoCI-derived peptides reflect their LPS-binding potential. These findings are in line with the hypothesis of Frecer et al. (33), who suggested, by using molecular modeling methods, that any peptide containing cationic/hydrophobic motifs within their sequence will recognize and bind LPS with high affinity. Indeed, such motifs are also involved in the interaction of, for instance, Lf and BPI with LPS (34). Our observations that apoCI-derived peptides containing the N-terminal helix without the previously established LPS-binding motif (i.e., apoCI1–30 and apoCI1-38) alter the in vivo behavior of LPS and increase the LPS-induced TNFα response are, therefore, likely explained by the presence of such amphipathic motifs.

The efficiencies of the apoCI-derived peptides to bind LPS and modulate the inflammatory response toward LPS were lower compared with full-length apoCI1–57. It is likely that the structural elements in both helices, represented by the alternating cationic/hydrophobic peptide motifs, act synergistically in the binding of LPS. A similar synergistic interaction with LPS has previously been demonstrated for Lf (35) and sheep myeloid antimicrobial peptide-29 (36), a sheep myeloid antimicrobial peptide, which both have two LPS-binding domains, and BPI (37) and serum amyloid P (34), which both have three regions that contribute to binding to LPS.

It is intriguing to speculate how apoCI interacts with LPS and enhances the LPS-induced proinflammatory response. LPS consists of four different moieties: 1) lipid A, the toxic moiety, 2) the inner core, 3) the outer core, and 4) the O-antigen. We previously reported that apoCI interacts with different forms of LPS from Salmonella minnesota [i.e., full-length wild-type LPS, and the truncated Re595 LPS, containing the lipid A moiety and some KDO sugars (19)], but more recently we also found that apoCI interacts with different types of LPS from Escherichia coli [i.e., O55:B5 LPS (20) and J5 LPS (Berbée and Rensen, unpublished observations)]. ApoCI thus interacts with both full-length, wild-type LPS and truncated forms of LPS, which indicates that the lipid A/KDO moiety of the LPS molecule contains the crucial elements for interaction with apoCI. Because apoCI is highly positively charged, we hypothesize that the amphipathic motifs within apoCI interact with the lipid A moiety via the negatively charged phosphate groups. Indeed, we found that apoCI interacts with the lipid A moiety. Similar to the effect of apoCI on the serum residence and liver uptake of 125I-LPS, apoCI markedly enhanced the serum residence of 125I-lipid A (29.7 ± 0.3% compared with 2.2 ± 0.4% for 125I-lipid A alone) and inhibited the liver uptake (36.3 ± 0.6% vs. 66.5 ± 6.0%) at a 1:1 molar ratio (not shown). Because lipid A is the common determinant of LPS molecules from all bacterial species, apoCI is likely to bind a wide array of wild-type and mutant LPS molecules.

ApoCI is able to enhance the proinflammatory response toward LPS via a direct interaction with LPS in vitro and in vivo. Thus far, other proteins that have been reported to bind LPS (e.g., serum amyloid P, apoE, Lf, and LALF) attenuate rather than stimulate the LPS-induced inflammatory response, except for LBP and CD14, which are required for LPS signaling (38, 39). We conclusively demonstrate by using TLR4-mutant mice that apoCI augments the LPS response by enhancing TLR4-dependent signaling. Although the LDL receptor (40, 41) and scavenger receptors, such as scavenger receptor class A (42–44) and BI (45–47), modulate inflammatory responses to LPS, these receptors apparently are not involved in the stimulating effect of apoCI on the LPS response. Next to TLR4, we show that the stimulating effect of apoCI is also dependent on functional CD14. An anti-CD14 antibody completely blocked the augmenting effect of apoCI, whereas co-incubation with sCD14 synergistically enhanced the effect of apoCI on the LPS-induced inflammatory response. Interestingly, co-incubation experiments of apoCI with LBP indicate that apoCI augments the LPS-induced inflammatory response via a similar mechanism as LBP does, by presenting the LPS toward CD14. Based on these findings, we now propose the following mechanism. Plasma apoCI, either bound to lipoproteins or moving freely in plasma, interacts with the lipid A part of LPS, presumably via the negatively charged phosphate groups, and subsequently transfers the LPS to either membrane-bound CD14 or sCD14, which ultimately presents the LPS to the MD2/TLR4 complex, thereby activating the TLR4-dependent inflammatory response.

In summary, we have demonstrated that apoCI contains structural elements in both its N-terminal and C-terminal helix to bind LPS, to modulate the in vivo behavior of LPS, and to enhance the TLR4-dependent proinflammatory response toward LPS in vitro and in vivo via an LBP-like mechanism. We anticipate that, in addition to the previously identified LPS-binding motif, the highly conserved alternating cationic/hydrophobic motifs present throughout the apoCI sequence participate in the binding to LPS and enhance the biological response to LPS.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- ApoCI

- apolipoprotein CI

- BPI

- bactericidal/permeability increasing protein

- CAP-18

- cationic antimicrobial peptide-18

- LALF

- Limulus anti-lipopolysaccharide factor

- LBP

- lipopolysaccharide-binding protein

- Lf

- lactoferrin

- LPL

- lipoprotein lipase

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- MD2

- myeloid differentiation protein-2

- TLR4

- Toll-like receptor 4

- TNFα

- tumor necrosis factor α

This work was supported in part by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO RIDE 014-90-001 to L.M.H., NWO VIDI 917-36-351 to P.C.N.R.), by the Netherlands Heart Foundation (NHS 2005B226 to P.C.N.R.), and by the Leiden University Medical Center (Gisela Thier Fellowship to P.C.N.R.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Harris R. L., Musher D. M., Bloom K., Gathe J., Rice L., Sugarman B., Williams T. W., Jr., Young E. J. 1987. Manifestations of sepsis. Arch. Intern. Med. 147: 1895–1906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poltorak A., He X., Smirnova I., Liu M. Y., van Huffel C., Du X., Birdwell D., Alejos E., Silva M., Galanos C., et al. 1998. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 282: 2085–2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimazu R., Akashi S., Ogata H., Nagai Y., Fukudome K., Miyake K., Kimoto M. 1999. MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4. J. Exp. Med. 189: 1777–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagai Y., Akashi S., Nagafuku M., Ogata M., Iwakura Y., Akira S., Kitamura T., Kosugi A., Kimoto M., Miyake K. 2002. Essential role of MD-2 in LPS responsiveness and TLR4 distribution. Nat. Immunol. 3: 667–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi M., Saitoh S., Tanimura N., Takahashi K., Kawasaki K., Nishijima M., Fujimoto Y., Fukase K., Akashi-Takamura S., Miyake K. 2006. Regulatory roles for MD-2 and TLR4 in ligand-induced receptor clustering. J. Immunol. 176: 6211–6218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mancek M., Pristovsek P., Jerala R. 2002. Identification of LPS-binding peptide fragment of MD-2, a toll-receptor accessory protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 292: 880–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Netea M. G., van der Meer J. W., van Deuren M., Kullberg B. J. 2003. Proinflammatory cytokines and sepsis syndrome: not enough, or too much of a good thing? Trends Immunol. 24: 254–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bone R. C. 1991. The pathogenesis of sepsis. Ann. Intern. Med. 115: 457–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bone R. C., Grodzin C. J., Balk R. A. 1997. Sepsis: a new hypothesis for pathogenesis of the disease process. Chest. 112: 235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berbee J. F., van der Hoogt C. C., Sundararaman D., Havekes L. M., Rensen P. C. 2005. Severe hypertriglyceridemia in human APOC1 transgenic mice is caused by apoC-I-induced inhibition of LPL. J. Lipid Res. 46: 297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Havel R. J., Fielding C. J., Olivecrona T., Shore V. G., Fielding P. E., Egelrud T. 1973. Cofactor activity of protein components of human very low density lipoproteins in the hydrolysis of triglycerides by lipoproteins lipase from different sources. Biochemistry. 12: 1828–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sehayek E., Eisenberg S. 1991. Mechanisms of inhibition by apolipoprotein C of apolipoprotein E-dependent cellular metabolism of human triglyceride-rich lipoproteins through the low density lipoprotein receptor pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 266: 18259–18267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weisgraber K. H., Mahley R. W., Kowal R. C., Herz J., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. 1990. Apolipoprotein C–I modulates the interaction of apolipoprotein E with beta-migrating very low density lipoproteins (beta-VLDL) and inhibits binding of beta-VLDL to low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J. Biol. Chem. 265: 22453–22459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beamer L. J., Carroll S. F., Eisenberg D. 1997. Crystal structure of human BPI and two bound phospholipids at 2.4 angstrom resolution. Science. 276: 1861–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rozek A., Sparrow J. T., Weisgraber K. H., Cushley R. J. 1999. Conformation of human apolipoprotein C–I in a lipid-mimetic environment determined by CD and NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 38: 14475–14484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barlage S., Frohlich D., Bottcher A., Jauhiainen M., Muller H. P., Noetzel F., Rothe G., Schutt C., Linke R. P., Lackner K. J., et al. 2001. ApoE-containing high density lipoproteins and phospholipid transfer protein activity increase in patients with a systemic inflammatory response. J. Lipid Res. 42: 281–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berbee J. F., van der Hoogt C. C., de Haas C. J., van Kessel K. P., Dallinga-Thie G. M., Romijn J. A., Havekes L. M., van Leeuwen H. J., Rensen P. C. 2008. Plasma apolipoprotein CI correlates with increased survival in patients with severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 34: 907–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L., Thompson P. A., Kitchens R. L. 2008. Infection induces a positive acute phase apolipoprotein E response from a negative acute phase gene: role of hepatic LDL receptors. J. Lipid Res. 49: 1782–1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berbee J. F., van der Hoogt C. C., Kleemann R., Schippers E. F., Kitchens R. L., van Dissel J. T., Bakker-Woudenberg I. A., Havekes L. M., Rensen P. C. 2006. Apolipoprotein CI stimulates the response to lipopolysaccharide and reduces mortality in Gram-negative sepsis. FASEB J. 20: 2162–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westerterp M., Berbee J. F., Pires N. M., van Mierlo G. J., Kleemann R., Romijn J. A., Havekes L. M., Rensen P. C. 2007. Apolipoprotein C–I is crucially involved in lipopolysaccharide-induced atherosclerosis development in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Circulation. 116: 2173–2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schippers E. F., Berbee J. F., van Disseldorp I. M., Versteegh M. I., Havekes L. M., Rensen P. C., van Dissel J. T. 2008. Preoperative apolipoprotein CI levels correlate positively with the proinflammatory response in patients experiencing endotoxemia following elective cardiac surgery. Intensive Care Med. 34: 1492–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berbee J. F., Mooijaart S. P., de Craen A. J., Havekes L. M., van Heemst D., Rensen P. C., Westendorp R. G. 2008. Plasma apolipoprotein CI protects against mortality from infection in old age. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 63: 122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoess A., Watson S., Siber G. R., Liddington R. 1993. Crystal structure of an endotoxin-neutralizing protein from the horseshoe crab, Limulus anti-LPS factor, at 1.5 A resolution. EMBO J. 12: 3351–3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larrick J. W., Hirata M., Zheng H., Zhong J., Bolin D., Cavaillon J. M., Warren H. S., Wright S. C. 1994. A novel granulocyte-derived peptide with lipopolysaccharide-neutralizing activity. J. Immunol. 152: 231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor A. H., Heavner G., Nedelman M., Sherris D., Brunt E., Knight D., Ghrayeb J. 1995. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) neutralizing peptides reveal a lipid A binding site of LPS binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 17934–17938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elass-Rochard E., Roseanu A., Legrand D., Trif M., Salmon V., Motas C., Montreuil J., Spik G. 1995. Lactoferrin-lipopolysaccharide interaction: involvement of the 28–34 loop region of human lactoferrin in the high-affinity binding to Escherichia coli 055B5 lipopolysaccharide. Biochem. J. 312: 839–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynch J. R., Tang W., Wang H., Vitek M. P., Bennett E. R., Sullivan P. M., Warner D. S., Laskowitz D. T. 2003. APOE genotype and an ApoE-mimetic peptide modify the systemic and central nervous system inflammatory response. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 48529–48533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffer M. J., van Eck M. M., Havekes L. M., Hofker M. H., Frants R. R. 1993. The mouse apolipoprotein C1 gene: structure and expression. Genomics. 18: 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tjabringa G. S., Aarbiou J., Ninaber D. K., Drijfhout J. W., Sorensen O. E., Borregaard N., Rabe K. F., Hiemstra P. S. 2003. The antimicrobial peptide LL-37 activates innate immunity at the airway epithelial surface by transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Immunol. 171: 6690–6696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ulevitch R. J. 1978. The preparation and characterization of a radioiodinated bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Immunochemistry. 15: 157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jong M. C., Rensen P. C., Dahlmans V. E., van der Boom H., van Berkel T. J., Havekes L. M. 2001. Apolipoprotein C–III deficiency accelerates triglyceride hydrolysis by lipoprotein lipase in wild-type and apoE knockout mice. J. Lipid Res. 42: 1578–1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rensen P. C., Herijgers N., Netscher M. H., Meskers S. C., van Eck M., van Berkel T. J. 1997. Particle size determines the specificity of apolipoprotein E-containing triglyceride-rich emulsions for the LDL receptor versus hepatic remnant receptor in vivo. J. Lipid Res. 38: 1070–1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frecer V., Ho B., Ding J. L. 2000. Interpretation of biological activity data of bacterial endotoxins by simple molecular models of mechanism of action. Eur. J. Biochem. 267: 837–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Haas C. J., van der Zee R., Benaissa-Trouw B., van Kessel K. P., Verhoef J., van Strijp J. A. 1999. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding synthetic peptides derived from serum amyloid P component neutralize LPS. Infect. Immun. 67: 2790–2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elass-Rochard E., Legrand D., Salmon V., Roseanu A., Trif M., Tobias P. S., Mazurier J., Spik G. 1998. Lactoferrin inhibits the endotoxin interaction with CD14 by competition with the lipopolysaccharide-binding protein. Infect. Immun. 66: 486–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tack B. F., Sawai M. V., Kearney W. R., Robertson A. D., Sherman M. A., Wang W., Hong T., Boo L. M., Wu H., Waring A. J., et al. 2002. SMAP-29 has two LPS-binding sites and a central hinge. Eur. J. Biochem. 269: 1181–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Little R. G., Kelner D. N., Lim E., Burke D. J., Conlon P. J. 1994. Functional domains of recombinant bactericidal/permeability increasing protein (rBPI23). J. Biol. Chem. 269: 1865–1872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ulevitch R. J., Tobias P. S. 1994. Recognition of endotoxin by cells leading to transmembrane signaling. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 6: 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ulevitch R. J., Tobias P. S. 1995. Receptor-dependent mechanisms of cell stimulation by bacterial endotoxin. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 13: 437–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Netea M. G., Demacker P. N., Kullberg B. J., Boerman O. C., Verschueren I., Stalenhoef A. F., van der Meer J. W. 1996. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice are protected against lethal endotoxemia and severe gram-negative infections. J. Clin. Invest. 97: 1366–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van den Elzen P., Garg S., Leon L., Brigl M., Leadbetter E. A., Gumperz J. E., Dascher C. C., Cheng T. Y., Sacks F. M., Illarionov P. A., et al. 2005. Apolipoprotein-mediated pathways of lipid antigen presentation. Nature. 437: 906–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki H., Kurihara Y., Takeya M., Kamada N., Kataoka M., Jishage K., Ueda O., Sakaguchi H., Higashi T., Suzuki T., et al. 1997. A role for macrophage scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis and susceptibility to infection. Nature. 386: 292–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hampton R. Y., Golenbock D. T., Penman M., Krieger M., Raetz C. R. 1991. Recognition and plasma clearance of endotoxin by scavenger receptors. Nature. 352: 342–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haworth R., Platt N., Keshav S., Hughes D., Darley E., Suzuki H., Kurihara Y., Kodama T., Gordon S. 1997. The macrophage scavenger receptor type A is expressed by activated macrophages and protects the host against lethal endotoxic shock. J. Exp. Med. 186: 1431–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bocharov A. V., Baranova I. N., Vishnyakova T. G., Remaley A. T., Csako G., Thomas F., Patterson A. P., Eggerman T. L. 2004. Targeting of scavenger receptor class B type I by synthetic amphipathic alpha-helical-containing peptides blocks lipopolysaccharide (LPS) uptake and LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine responses in THP-1 monocyte cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 36072–36082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li X. A., Guo L., Asmis R., Nikolova-Karakashian M., Smart E. J. 2006. Scavenger receptor BI prevents nitric oxide-induced cytotoxicity and endotoxin-induced death. Circ. Res. 98: e60–e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vishnyakova T. G., Bocharov A. V., Baranova I. N., Chen Z., Remaley A. T., Csako G., Eggerman T. L., Patterson A. P. 2003. Binding and internalization of lipopolysaccharide by Cla-1, a human orthologue of rodent scavenger receptor B1. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 22771–22780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]