Abstract

A liquid-helium temperature study of Fe2+ and Mn2+ ions has been carried out on a single crystal of Fe2+-doped ZnSiF6.6H2O at 5–35K at 170, 222.4 and 333.2 GHz. The spectra are found to be an overlap of two magnetically inequivalent Fe2+ ions, as well as that of an Mn2+ ion. From the simulation of the EPR line positions for the Fe2+ (d6, S=2) ion the spin-Hamiltonian parameters were estimated for the two inequivalent Fe2+ ions at the various temperatures. From the relative intensities of lines the absolute sign of the fine structure parameters have been estimated. In addition, the fine-structure and hyperfine-structure spin-Hamiltonian parameters for the Mn2+ ion, present as impurity at interstitial sites, were estimated from the hyperfine allowed and forbidden line positions. The particular virtues of such a single-crystal study vs. that on powders is noted.

Keywords: Multi-frequency EPR, High-frequency EPR, Spin-Hamiltonian Parameters, ZnSiF6.6H2O single crystal, Fe2+, Mn2+

1. Introduction

The non-Kramers Fe2+ ion was previously considered EPR silent, because it typically possesses a very large zero-field splitting, so that the quantum of energy at X-band (~9.5 GHz) is not sufficient to match the energy-level separation for the allowed transitions ΔM = ±1, where M is the electronic spin magnetic quantum number. In addition, its spin-lattice relaxation times are rather short at higher temperatures, so that the EPR lines are sufficiently broadened out, that they are not observed near room temperature. However, one can observe EPR transitions for the Fe2+ ion at low temperatures and at sufficiently high frequencies, such that the microwave energy is sufficient to match the required energy level separations. Recently, such studies, all on powder samples, have been reported: (i) Fe2+ in the Reduced Rubredoxin model [Fe(SPh)4]2− by Knapp et al. [1], (ii) Fe2+ in hexaaqua complexes by Telser et al. [2], (iii) Fe2+ in Bis(2,2′-bi-2-thiazoline)bis(isothiocyanato)iron(II) by Ozarowski et al. [3], (iv) Fe2+ in Fe(SO4).4H2O by Krzystek et al. [4, 5], (v) Fe2+ in [Fe2(μ-OH)3(tmtacn)2]2+ by Knapp et al. [6], and (vi) Fe2+ in CsFe(D2O)6PO4 by Carver et al. [7]. All these studies on biological samples containing undiluted Fe2+ ions were on amorphous powders or frozen solutions, and the values of the zero-field splitting (ZFS) parameter, D was quite large, ranging from 11,561 to 172,452 Gauss. It is the purpose of this paper to report on a detailed multifrequency EPR study of an Fe2+-doped single-crystal at very high frequencies (170, 222.4 and 331.2 GHz) yielding the temperature variation of the Fe2+ spectra from 5 to 35 K, and to estimate its spin-Hamiltonian parameters over this temperature range. The absolute sign of the zero-field splitting (ZFS) parameter, D, was estimated from the relative intensities of the lines at liquid-helium temperature. Mn2+, is present as an impurity in the chemicals used for growing the crystals. Its EPR spectra were also analyzed, and its spin-Hamiltonian parameters estimated.

2. Experimental arrangement

2.1 Spectrometers

170 GHz

EPR measurements at 170 GHz were carried out at 5–35 K at ACERT (Advanced Center for Electron Spin Resonance Technologies) at Cornell University on a home-built spectrometer, based on the principles of quasi-optics, operating in the induction-mode [8]. It is equipped with a Fabry-Pérot resonator, with a separation of 1–2 cm between the mirrors, which allows one to place large single crystals in it. A superconducting magnet was employed. The field was calibrated using a Mn2+ marker, g=2.0145, with a precision of 5–10 G. Magnetic field modulation at 82 kHz and 3–10 mT amplitude was employed. Under these standard operating conditions, the spectra obtained appear to be absorption curves, as though there were no modulation, instead of the usual first derivative ones. This is due to rapid passage effects as originally described by Portis [9]. Because of the low temperatures, the relaxation times are long and the conditions of rapid passage are fulfilled, (i.e., relaxation times are larger, than the period of modulation and the microwave field is larger than 1/(γT1) and 1/(γT2) [10]. Then the line is distorted into the shape of an absorption line.[Ref. X] Whereas the line shapes obtained in the rapid passage spectra are significantly modified, the line positions remain unchanged, as discussed by Chemerisov et al. [14] (Note that the use of the Fabry-Perot resonator with its substantial quality factor improves S/N, but it also enhances, B1 at the sample. In addition, it is sensitive to microphonics, preventing the use of modulation frequencies lower than ca. 80 kHz. These normal operating conditions undoubtedly enhanced the rapid passage effects.)

222.4 and 331.2 GHz

High-frequency EPR spectra at 222.4 and 331.2 GHz were recorded on a home-built spectrometer at the EMR facility of NHMFL (National High magnetic Field, Tallahassee, Florida). The instrument was a transmission-type device in which microwaves are propagated in cylindrical lightpipes. The microwaves were generated by a phase-locked Virginia Diodes source generating a frequency of 13 ± 1 GHz and producing harmonics of which the 4th, 8th, 16th, 24th and 32nd were available. A superconducting magnet (Oxford Instruments) capable of reaching a field of 17 T was employed. The field was calibrated using DPPH, g = 2.0037. The differences between ‘calibrated’ and ‘uncalibrated’ fields are 50–90 Gauss. No resonance cavity was used. Detection was provided by a liquid-helium-cooled InSb hot-electron bolometer (QMC Ltd., Cardiff, UK). Magnetic field modulation at 40 kHz and ca. 2 mT amplitude was employed. A Stanford SR830 lock-in amplifier was used to convert the modulated signal to a DC voltage.

2.2 Crystal: sample preparation and structure

ZnSiF6.6H2O crystals were grown by dissolving metallic zinc in fluosilicic acid and slowly evaporating the filtered solution at room temperature, to which was added FeSO4 solution in distilled water so that there was one Fe2+ ion for every 500 Zn2+ ions. A drop of very dilute fluosilicid acid was added to the solution to prevent hydrolysis. Crystals were selected from crops recrystallized from aqueous solution by slow evaporation. Nice single colourless prismatic crystals with hexagonal cross section were obtained within a few days. The clear color indicated that Fe3+ ions were not present, as they would otherwise impart a yellowish hue to the crystals. Elemental analysis confirmed that indeed Fe2+ ions were present in the sample. The crystals were stored in mineral oil to avoid deliquescence. The sample was covered with a layer of Apiezon grease to prevent oxidation and deliquescence inside the resonators.

The room temperature crystal structure of ZnSiF6.6H2O was determined by Ray et al. [12]. Accordingly, the crystals are characterized by the unit cell parameters: a = 9·363 (3), c = 9·690 (5) Å, Z = 3, with the space group R3̄. However, based on our EPR results described below a structural phase transition may occur at very low temperatures, so it is not clear whether this structure accurately describes the EPR spectra.

2.3 EPR spectra

No spectrum could be observed from room temperature (RT) down to ca. 40 K. [This confirms that Fe3+ ions are not present in the sample, since they do exhibit EPR lines at RT (295K).] Thus, the spectra were recorded only below 40 K, specifically at ca. 35, 20, 17, 10 and 5 K. The temperature variation of the EPR spectrum indicated that the site symmetry changed over the range of 35 K to 20 K, below which it remained unchanged. All these single-crystal spectra also display a central Mn2+ sextet in addition to the Fe2+ lines. Although the Mn2+ ion does normally exhibit an EPR spectrum at RT, no Mn2+ spectrum was seen at RT in the present case. This could be due to a Mn2+-Fe2+ interaction which would shorten the Mn2+ relaxation times, thereby broadening the Mn2+ EPR lines at higher temperatures.

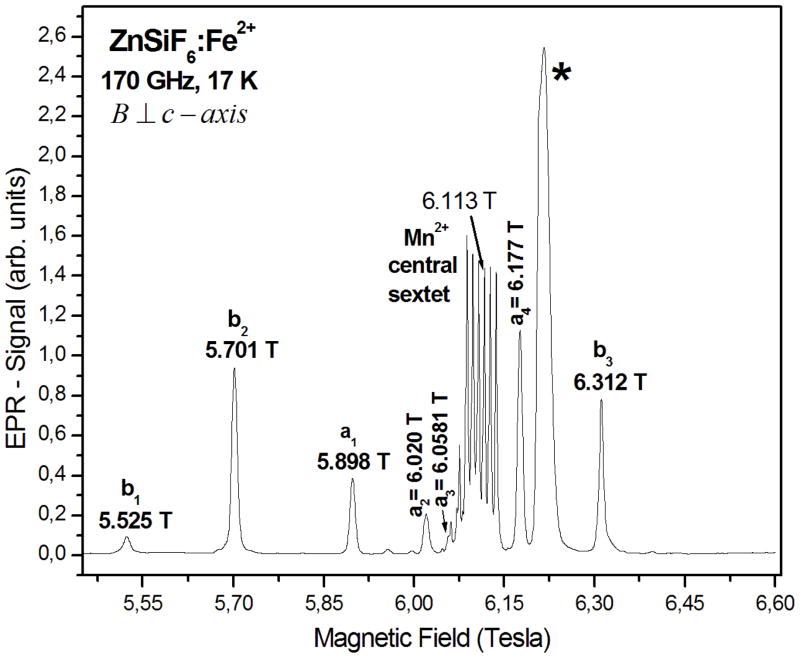

Figures 1 and 2, respectively, show the 5 K EPR absorption-like spectra at 170 GHz and the first-derivative EPR spectra at 222.4 GHz for the orientations with the external magnetic field (B) parallel and perpendicular to the c-axis, the latter being in the direction perpendicular to one of the sides of the hexagonal cross section of the single crystal. For each of these orientations of B, there are found two sets of spectra due to two magnetically inequivalent Fe2+ ions, hereafter referred to as Fe2+ ions at site a and b. Figure 3 shows the 10 K first–derivative EPR spectrum at 222.4 and 331.2 GHz for the magnetic field orientation parallel to the c-axis of the single crystal. At 17 K and 170 GHz the absorption-like spectrum observed is shown in Fig. 4 just for B oriented perpendicular to the c-axis of the single crystal. Also, at this temperature, the last line of site b could not be observed within the magnetic field range 5.2–6.6 T used for recording the spectrum. At 20 K, we just obtained the first-derivative spectrum at 222.4 GHz for B in the parallel orientation to the c-axis of the single crystal, as shown in Fig. 5. At 35 K the absorption-like spectrum observed at 170 GHz for B in the perpendicular orientation to the c-axis of the single crystal, is shown in Fig. 6. The lines due to the Fe2+ ions at sites a and b are indicated as (a1, a2, a3, a4) and (b1, b2, b3, b4), respectively, in order of increasing magnetic field in Figs. 1–6. The satellite lines observed at 222.4 and 331.2 GHz, as seen in Figs. 2, 3 and 5, are presumably due to superhyperfine interactions with the neighbouring Mn2+ impurities. The reciprocal interaction weakly splits the Mn2+ hyperfine lines as seen in the spectra.

Fig. 1.

170-GHz EPR absorption-like lines at 5.5 K for the orientation of B parallel and perpendicular to the crystal c-axis. The EPR lines belonging to the Fe2+ ions at the two sites are indicated as a1, a2, a3, a4 and b1, b2, b3, b4 in increasing value of the magnetic field. The indicated field values are as scaled from the plot; the precision is 5–10 G, as described in Sec. 2.1.

Fig. 2.

First-derivative 222.4-GHz EPR spectrum at 5 K for the orientation of B parallel and perpendicular to the crystal c-axis. The EPR lines belonging to the Fe2+ ions at the two sites are indicated as a1, a2, a3, a4 and b1, b2, b3, b4 in increasing value of the magnetic field. The inset in the figure for the perpendicular orientation of B shows an amplified view of the Mn2+ central hyperfine sextet, as well as the Fe2+ a2, a3 and a4 lines. The indicated field values are as scaled from the plot; the precision is 50–100 G, as described in Sec. 2.1. The low-frequency background is due to instrumental artefact.

Fig. 3.

222.4- and 331.2-GHz first-derivative EPR spectra at 10 K for the orientation of B parallel to the crystal c-axis in both cases. The EPR lines belonging to the Fe2+ ions at the two sites are indicated as a1, a2, a3, a4 and b1, b2, b3, b4 in increasing value of the magnetic field. The indicated field values are as scaled from the plot; the precision is 50–100 G, as described in Sec. 2.1. The low-frequency background is due to instrumental artefact.

Fig. 4.

170-GHz absorption-like EPR spectrum at 17 K for the orientation of B perpendicular to the crystal c-axis. The EPR lines belonging to the Fe2+ ions at the two sites are indicated as a1, a2, a3, a4 and b1, b2, b3, b4 in increasing value of the magnetic field. The line indicated by * is not a Fe2+ resonance; it is probably due to an instantaeous glitch in the magnetic field. The highest field line, b4, for site b is not observed within the range of the magnetic field swept. The indicated field values are as scaled from the plot; the precision is 5–10 G, as described in Sec. 2.1.

Fig. 5.

First-derivative 222.4-GHz EPR spectrum at 20 K for the orientation of B parallel to the crystals c-axis. The EPR lines belonging to the Fe2+ ions at the two sites are indicated as a1, a2, a3, a4 and b1, b2, b3, b4 in increasing value of the magnetic field. The indicated field values are as scaled from the plot; the precision is 50–100 G, as described in Sec. 2.1.

Fig. 6.

170-GHz absorption-like EPR spectrum at 35 K for the orientation of B perpendicular to the crystal c-axis. The EPR lines belonging to the Fe2+ ions at the two sites are indicated as a1, a2, a3, a4 and b1, b2, b3, b4 in increasing value of the magnetic field. The indicated field values are as scaled from the plot; the precision is 5–10 G, as described in Sec. 2.1.

3. Analysis of Fe2+ EPR spectra

3.1 Spin Hamiltonian (SH)

The EPR spectral line positions observed at the various temperatures and for different orientations of B were fitted simultaneously to estimate the SH parameters for the Fe2+ (S=2 spin state) characterized by orthorhombic symmetry, including the second and fourth order zero-field splitting (ZFS) terms [13,14].

| (1) |

where μB is the Bohr magneton; the magnetic z-axis is along the respective symmetry axes, which are parallel and perpendicular to the c-axis of the crystal for sites a and b, respectively, and the are spin operators [13,14]. Inclusion of a small second order term depending on E and the fourth-order term improved the quality of the fits significantly. The very small values of E (Table 1) indicate that the Fe2+ ions see a predominantly axial field with a very small (trigonal) distortion in the ZnSiF6.6H2O crystal. The last two terms in Eq. (1) were found to have negligible effects on the fitting. Thus, within experimental error, the values of the non-axial parameters and can be assumed to be zero.

TABLE 1.

Fe2+ spin-Hamiltonian parameters in the ZnSiF6.6H2O single crystal at various temperatures. D, E and are given in units of Gauss.

| site a | site b | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (K) | g|| | g⊥ | D (G) | E (G) | g|| | g⊥ | D (G) | E (G) | ||||

| 5 | 1.984 | 2.014 | −635 | 10 | 3.8 | 2.029 | 1.986 | −1920 | 25 | 8.4 | ||

| 10 | 1.992 | - | −615 | 0 | 3.4 | - | 1.992 | −1995 | 25 | 8.3 | ||

| 17 | - | 2.012 | −860 | 5 | 4.4 | 2.022 | - | −1840 | 0 | 10.5 | ||

| 20 | 1.996 | - | −880 | 0 | 6.1 | - | 1.992 | −1970 | 25 | 10.2 | ||

| 35 | - | 1.989 | −798 | 2 | −5.5 | 1.994 | - | −765 | 0 | 5.3 | ||

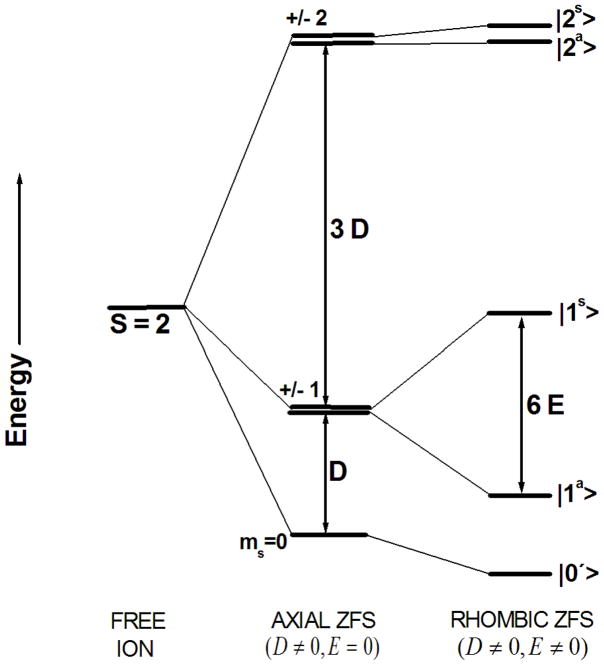

3.2 Zero-field energy levels

The zero-field energy levels are shown in Fig. 7 for positive D [6]. In the absence of any ZFS (Fig. 7 left), the S = 2 spin system of the Fe2+ ion possesses five degenerate energy levels (M = ±2, ±1, 0). These are split by the ZFS terms, i.e. the second and subsequent terms in Eq. (1), thereby lifting the degeneracy. The splitting in the middle of Fig. 7 is caused by an axial field (D ≠ 0, E = 0), whereas the splitting shown in the right part of this figure is caused by a rhombic distortion (D ≠ 0, E ≠ 0). The five zero-field eigenfunctions depending on D and E are expressed as follows:

| (2a) |

| (2b) |

| (2c) |

| (2d) |

| (2e) |

Fig. 7.

Zero-field energy levels of a 5D 3d6 (S=2) ion with axial (D) and rhombic (E) zero-field splitting, with D, E taken as > 0. In our case, the order of these energy levels is reversed, since D < 0. The axial field splits the spin quintet into a singlet (ms = 0) and two dublets (ms = ±1, ±2). These doublets are further split by the rhombic field, described by the eigenectors |2s>, |2a>, |1s>, |2a>; where the superscripts s and a stand for symmetric and anti-symmetric wavefunctions.

At very high magnetic fields the energies of these levels will increase linearly with the magnetic field (B) intensity for the orientation of B parallel to the magnetic z-axis of the crystal, when the Zeeman term is taken into account.

3.3 Relative intensities of EPR lines and the absolute sign of the ZFS parameter D

For the orientation of B parallel to the c-axis, which is parallel to the z- and x-axes of the Fe2+ ions at sites a and b, respectively, the intensities of the higher field lines a4 and b4 are smaller and larger relative to the lower field lines a1 and b1, respectively. This indicates the absolute sign of D to be negative for both the sites a and b, according to the discussion given by Abragam and Bleaney [13], taking into account the transformation of the ZFS parameter D from the magnetic x- to the z-axis for site b. The sign of the other SH parameters relative to D as found from the fitting are correct. The signs of the SH parameters in Table 1 are listed in accordance with this.

3.4 Evaluation of Fe2+ SH parameters from EPR line positions

The spin-Hamiltonian parameters which simultaneously best reproduce the line positions for all the frequencies of measurement at each temperature were determined with a simulation algorithm, developed by Ozarowski [15], that calculates EPR line positions for any orientation of the magnetic field with respect to the crystal axes, using matrix diagonalization. In Table 1 these values for the SH parameters g||, g⊥, D, E and are listed. It is noted that the value of E is very small, since and are zero, they are not listed. Tables 2–6 list the calculated and experimental line positions at 5, 10, 17, 20 and 35 K, respectively, as well as their % deviations, as calculated using the best-fit parameters listed in Table 1. The good fits at all frequencies and temperatures are fully consistent with an S= 2 ion

TABLE 2.

Experimental (exp.) and calculated (calc.) line positions in Tesla for the 170-GHz EPR spectrum at 5.5 K for the orientation of B parallel and perpendicular to the crystal c-axis.

| site a (B || c-axis) | site a (B ⊥ c-axis) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| exp. | 5.9457 | 6.0278 | 6.2525 | 6.2895 | 5.909 | 6.014 | 6.048 | 6.143 |

| calc. | 5.9517 | 6.0117 | 6.2314 | 6.2903 | 5.922 | 6.0137 | 6.0453 | 6.1378 |

| PD (%) | 0.101 | 0.267 | 0.340 | 0.006 | 0.220 | 0.005 | 0.045 | 0.085 |

| site b (B || c-axis) | Site b (B ⊥ c-axis) | |||||||

| exp. | 5.8162 | 6.0651 | 6.1739 | 6.4486 | 5.469 | 5.729 | 6.288 | 6.463 |

| calc. | 5.8202 | 6.0663 | 6.1862 | 6.4449 | 5.4649 | 5.6962 | 6.2746 | 6.5037 |

| PD (%) | 0.069 | 0.020 | 0.199 | 0.057 | 0.075 | 0.573 | 0.2131 | 0.630 |

TABLE 6.

Experimental (exp.) and calculated (calc.) line positions in Tesla for the 222.4-GHz EPR spectrum at 20 K for the orientation of B parallel to the crystal c-axis. PD (%) has been defined in the caption of Table 2.

| site a (B || c-axis) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| exp. | 7.728 | 7.806 | 8.135 | 8.172 |

| calc. | 7.7297 | 7.7970 | 8.1208 | 8.1860 |

| PD (%) | 0.022 | 0.115 | 0.175 | 0.171 |

| site b (B || c-axis) | ||||

| exp. | 7.655 | 7.917 | 8.016 | 8.313 |

| calc. | 7.6455 | 7.9147 | 8.0283 | 8.3059 |

| PD (%) | 0.124 | 0.029 | 0.153 | 0.085 |

The magnetic z-axes for the two sites were found to be oriented along the directions parallel and perpendicular to the c-axis. This perpendicular direction is also perpendicular to an edge of the hexagonal cross section as shown in Figure 8, which depicts the two sets of magnetic axes in relation to crystal morphology of hexagonal prismatic crystals. From the observed equal intensities of the EPR lines for the Fe2+ ions at sites a and b, it was concluded that in the six equivalent sites of b corresponding to the six edges of the hexagonal cross section of the crystal, and perpendicular to the c-axis of the crystal which corresponds site a, the Fe2+ ions are statistically distributed equally, and in a manner such that the intensities of the EPR lines are about the same for the two sites a and b. Since at temperatures higher than 5 K, the spectra were recorded for only one orientation of B, either parallel or perpendicular to the c-axis, only the values of g||(a), g⊥(b) or g|| (b), g⊥(a) could be determined from the spectral line positions in those cases. At 5 K in the perpendicular orientation for B, the spectrum for 222.4 GHz shown in Fig. 2 displays a rather intense Mn2+ central sextet. A closer look at this sextet, as shown in the inset of Fig. 2 reveals that there are two Fe2+ lines which overlap these Mn2+ lines.

Fig. 8.

A drawing of the hexagonal cross section of the ZnSiF6.6H2O single crystal. For site a the magnetic z-axis is along the symmetry, c-axis, of the crystal, whereas for site b the magnetic z-axis is perpendicular to the c-axis of the crystal.

Examining the values of the SH parameters at all temperatures as listed in Table 1, it is seen that E, the parameter that indicates rhombic distortion of the axial field is relatively very small as already noted. Specifically |E|< 10G for site a and |E|< 25G for site b, which amounts to |E/D|  0.02 for site a and |E/D|

0.02 for site a and |E/D|  0.01 for site b. This implies that any departure from axial symmetry is extremely small. It is further noted, that the values of g||, g⊥ and D, in Table 1 for 35 K are substantially different from those at 5–20 K. This indicates that the crystal undergoes some kind of a phase transition between 35 and 20 K. At 35K, it would appear that sites a and b become almost equivalent., as the values of D for the two sites are about the same.

0.01 for site b. This implies that any departure from axial symmetry is extremely small. It is further noted, that the values of g||, g⊥ and D, in Table 1 for 35 K are substantially different from those at 5–20 K. This indicates that the crystal undergoes some kind of a phase transition between 35 and 20 K. At 35K, it would appear that sites a and b become almost equivalent., as the values of D for the two sites are about the same.

4. Analysis of Mn2+ EPR spectra

The Mn2+ EPR spectrum is always present in the low temperature spectra studied. It is first noted that the Mn2+ central sextet becomes very sharp at high magnetic fields, because of suppression of second-order perturbation terms due to the Zeeman term becoming rather dominant. They are weakly split due to interaction with the Fe2+ ions in the vicinity. Of these, the 222.4 GHz EPR spectrum, in Fig. 9, shows all the pertinent features clearly. In this spectrum, a central Mn2+ sextet appears at about 7.9 T, similar to that in a polycrystalline host [16, 17]; reflecting the manner in which the Mn2+ ions enter interstitially in the ZnSiF6.6H2O single crystal. In addition, a non-central Mn2+ hyperfine sextet is observed at about 2.76 T. (In fact, there are eight lines seen here; there appears to be an overlap due to another Mn2+ species, characterized by almost the same parameters.) The polycrystalline Mn2+ spectrum is well understood; the estimation of the zero–field splitting parameters from the hyperfine doublet separations is described in detail by Misra [16, 17]. The spin Hamiltonian for the Mn2+ ion (electron spin S=5/2, nuclear spin I = 5/2) in an orthorhombic site symmetry is given by [17]:

| (2) |

Fig. 9.

First-derivative Fe2+ EPR spectrum in the ZnSiF6.6H2O single crystal at 222.4 GHz (5K). The insets show amplified views of the Mn2+ hyperfine sextets. The calculated line positions for Mn2+ with the parameters: g = 2.01452 and D = − 65847.15 as estimated in Sec. 3 are indicated as CAL below the plot of the spectrum. The indicated field values are as scaled from the plot; the precision is 50–100 G, as described in Sec. 2.1.

In (2) gN and μN are the nuclear g factor and nuclear magneton, respectively. In this equation the first three terms represent the electron-Zeeman, nuclear-Zeeman and the electron-nuclear hyperfine interactions. HZFS is the zero-field splitting (ZFS) term, which can be written for non-axial (orthorhombic) symmetry as:

| (3) |

Here, z denotes the principal axis of the second order ZFS tensor; again D and E are the axial and orthorhombic ZFS parameters, and S± = Sx ± iSy. In [17], a formula is provided, which allows one to estimate the value of the ZFS parameter D for the Mn2+ ion from the splitting of the forbidden hyperfine lines (Δm = ±1, where m is the nuclear magnetic quantum number) of the Mn2+ central sextet shown in Fig. 10:

| (4) |

where |ΔBex| is the experimentally observed separation between the two peaks corresponding to the two hyperfine forbidden transitions, B0 is the center of the hyperfine sextet, G0 = hν, ν is the resonance frequency, and A is the hyperfine-interaction constant, , and

Fig. 10.

A magnified view of the Mn2+ central sextet in the 222.4 GHz spectrum at 5K. The positions of the five forbidden doublets are indicated as F1 and F2. The allowed hyperfine lines are indicated as 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. The indicated field values are as scaled from the plot; the precision is 50–100 G, as described in Sec. 2.1.

| (5) |

Each of the six (2I+1=6) intense lines in the hyperfine sextet in Fig. 10 is an allowed hyperfine line (Δm = 0), indicated as 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. To the right (i.e. higher magnetic field) of each allowed hyperfine line and in between adjacent allowed hyperfine lines, the five sets of hyperfine forbidden doublets, indicated as F1 and F2, are observed (Fig. 10). It is noted, that between the allowed hyperfine lines 4 and 5 there appears a third line, which does not belong to the Mn2+ hyperfine sextet being considered.

Calculation of the value of the ZFS parameter D for the Mn2+ ion

The values of B0, the center of the hyperfine sextet, , the average distance between adjacent hyperfine lines, as well as the average separation between two adjacent forbidden hyperfine lines as shown in Fig. 10 are estimated as follows: B = 78878 G; . Using μBgMnB0 = hν (ν = 222.4 GHz), the value of gMn for the Mn2+ ion is: gMn = hν/μBB0 = 2.01452. Using this and the free-electron g-value (ge = 2.0023), the hyperfine splitting constant A can be calculated in units of Gauss: . Now, for use in Eq. (4), . For E = 0, assuming axial symmetry, one obtains from Eqs. (5) and (6): η = E/D = 0 and F(η) =1. Finally, using these values, D can be calculated, using Eq. (4), to be: D(±) = ±65, 847.15 G. The discussion below shows that the minus sign in Eq. (4) should be chosen to fit the intensities of the two observed sextets, although the choice of sign does not affect the calculated line positions.

Comparison of the calculated values of the Mn2+ line positions with the experimental values as shown in Figure 9

The values estimated here for g and D have been used to simulate the Mn2+ line positions in the 2–12 T range at 222.4 GHz. They are marked as ‘CAL’ in Fig 9. It is noted that the negative sign has been used for D in the simulation rather than the positive sign, to obtain the intensities of the lines consistent with the experiment. Only two allowed fine-structure EPR lines of the Mn2+ ion occur in the 2–12 T range swept in the experimental spectrum. The calculated lines at 2.856T and 8.549T are very close to the centers of the corresponding experimentally observed sextets at 2.76T and 7.888T. These calculated values are in good agreement with these observed experimentally, given that they were only derived using the D value obtained from the central hyperfine sextet in a polycrystalline spectrum. The rather large value of D for the Mn2+ ion also explains why the remaining allowed Mn2+ lines are not observed in the 2–12 T magnetic field range, since they lie outside this range.

5. Discussion and concluding remarks

The salient features of the present EPR study on the Fe2+ ion in a single crystal of ZnSiF6.6H2O are described as follows.

(i) There exist two magnetically inequivalent Fe2+ ions. The magnetic z-axes of these ions are oriented parallel and perpendicular to the c-axis of the crystal, referred as Fe2+ ions at sites a and b respectively. Thus, there are six equivalent Fe2+ ions at site b due to the crystal symmetry, which are statistically distributed equally in these orientations, as deduced from almost equal intensities of EPR lines for sites a and the ensemble of six b-sites.

(ii) The SH parameters have been estimated for the two magnetically inequivalent ions as deduced from calculated line positions. The value of the zero-field splitting parameter, |D|, for Fe2+ is not very large, ranging from 600–2000 G for the two sites in this 0.5% doped single crystal, unlike these observed in biological systems with 100% Fe2+ ions[1–7, 18], which are at least an order of magnitude larger. (iii) The EPR spectra are only observed below 40 K, presumably because the spin-lattice relaxation times are too short at higher temperatures, so that the EPR lines are broadened out.

(iv) The Mn2+ ion enters the lattice of ZnSiF6.6H2O crystal at interstitial positions, yielding a polycrystalline spectrum.

(v) From the Mn2+ central hyperfine sextet the values of the SH parameters g and D have been estimated as well as, the value of the hyperfine constant A. These SH parameters do produce values quite close to those observed at 222.4 GHz. The absolute sign of the ZFS parameter D for Mn2+ has been determined to be negative.

(vi) The virtues of the single-crystal study over and above that of a powder sample are as follows. (a) Since the spectrum in the crystal is obtained for a single orientation of the magnetic field with respect to the crystal axes, the lines are much sharper, hence of greatly increased amplitude, than those in a powder sample which shows a distribution of signals obtained for a continuous range of orientations with respect to the magnetic field. In addition, the denser packing in the single crystal leads to the intensities of the lines being greater than those in a powder sample. (b) The observation that there are two magnetically inequivalent ions present was only possible in a single crystal. In a powder sample, their spectra would be indistinguishable. (c) Since the two magnetically inequivalent sites are clearly discerned, it was possible to deduce the absolute signs of the SH parameters from the relative intensities of the EPR lines for the two sites at liquid helium temperatures. (d) The SH parameters for the two sites were unequivocally determined for the single crystal. This would not be possible in a powder spectrum.

It is hoped that the present study will stimulate further investigations into the structural and magnetic phase transitions undergone by the crystal at liquid-helium temperatures. For example, it would be of interest to study the high-field EPR spectra as a function of concentration of the Fe2+ dopant.

Other somewhat related studies include the early X-band EPR study on 2% Fe2+ doped ZnSiF6·6H2O by Rubins [19] and the FIR-magnetic resonance study on FeSiF6·6H2O by Champion and Sievers [20]. According to the calculations of Palumbo [21] for the 3d6 Fe2+ ion, with the electronic ground state 5D (L=2, S=2) in a trigonal crystal field, a cubic field splits the orbital levels into an upper doublet and a lower triple. The trigonal field splits the triplet, so that an orbital singlet lies lowest for the case when the trigonal field (δ = 1200 cm−1) is much greater than the magnitude of the spin-orbit coupling constant (λ = −104 cm−1). The five-fold spin multiplicity of this orbital singlet is split by the spin-orbit interaction into a ground singlet with the excited doublets at D (MS = ±1) and 4D (MS = ±2) above it, consistent with the second-order ZFS part of the spin Hamiltonian, given by Eq. (1). At X-band, Rubins [19] just observed the forbidden (ΔMS = ±2) transitions of the excited orbital doublet MS = ±1 of the spin quintet, as shown in Fig. 7.. He also points out that there is a “steady change in the crystal field parameters with increasing Fe2+ concentration.” By contrast, we have been able to observe all the allowed (ΔMS = ±1) transitions possible within the spin quintet (S=2) at a substantially reduced Fe2+ concentration. Thus, in our study the ZnSiF6·6H2O (ZFS) crystal field is likely significantly less perturbed by the Fe2+ ions, because of the low concentration. Our observation of |D| ≲ 2 kG is substantially smaller than that observed by Rubins [19] and by Champion and Sievers [20] [in pure FeSiF6·6H2O (FFS)] of ~ 10 cm−1 × ~12.5 kG/cm−1= 125 kG. Yi-Yang and Min-Guang [22], have given theoretical expressions for D and E for Fe2+ sites in FFS. According to these expressions just the spin-spin interaction for Fe2+ yields a D~6.75 kG (using their value of ρ = 0.18 cm−1). However, these calculations for FFS are made for D > 0, for which the spin singlet (MS = 0) lies lowest, as shown in Fig. 7. In our case, for ZFS with very small concentration of Fe2+ ions, this is not the case as D < 0, so that the energy-level order of the spin quintet is reversed from that for FFS (Fig. 7). In addition, these theoretical estimates of the ZFS parameters do not take into account the paramagnetic ions in the vicinity.

It is noted that the Fe2+ ions exhibit very highly axial crystal fields with small non-axial distortion in the doped ZnSiF6·6H2O crystal, according to the values of the spin-Hamiltonian parameters determined here. It is likely that there occurs a Jahn-Teller distortion at Fe2+ sites in our crystal at lower temperatures; e.g. see [23] and references therein.

TABLE 2. Experimental (exp.) and calculated (calc.) line positions in Tesla for the 170-GHz EPR spectrum at 5.5 K for the orientation of B parallel and perpendicular to the crystal c-axis.

TABLE 3.

Experimental (exp.) and calculated (calc.) line positions in Tesla for the 222.4-GHz EPR spectrum at 5 K for the orientation of B parallel and perpendicular to the crystal c-axis. PD (%) has been defined in the caption of Table 2.

| site a (B || c-axis) | site a (B ⊥ c-axis) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| exp. | 7.821 | 7.890 | 8.1042 | 8.1409 | 7.794 | 7.895 | 7.905 | 7.9937 |

| calc. | 7.8390 | 7.8979 | 8.1176 | 8.1776 | 7.7811 | 7.8716 | 7.9042 | 7.9967 |

| PD (%) | 0.230 | 0.100 | 0.165 | 0.451 | 0.166 | 0.296 | 0.010 | 0.038 |

| site b (B || c-axis) | Site b (B ⊥ c-axis) | |||||||

| exp. | 7.661 | 7.934 | 8.0576 | 8.318 | 7.255 | 7.549 | 8.125 | 8.362 |

| calc. | 7.66792 | 7.9336 | 8.0577 | 8.3206 | 7.3111 | 7.5425 | 8.1187 | 8.3500 |

| PD (%) | 0.090 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.031 | 0.773 | 0.086 | 0.078 | 0.144 |

TABLE 4.

Experimental (exp.) and calculated (calc.) line positions in Tesla for the 222.4-GHz EPR spectrum at 10 K for the orientation of B parallel to the crystal c-axis. PD (%) has been defined in the caption of Table 2.

| site a (B || c-axis)/222.4 GHz | site a (B || c-axis)/331.2 GHz | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| exp. | 7.818 | 7.887 | 8.102 | 8.1385 | 11.704 | 11.771 | 11.982 | 12.018 |

| calc. | 7.8117 | 7.8737 | 8.0787 | 8.1407 | 11.7129 | 11.7750 | 11.9811 | 12.0431 |

| PD (%) | 0.081 | 0.169 | 0.288 | 0.027 | 0.076 | 0.034 | 0.008 | 0.209 |

| site b (B || c-axis)/222.4 GHz | Site b (B ||c-axis)/331.2 GHz | |||||||

| exp. | 7.656 | 7.917 | 8.052 | 8.313 | 11.544 | 11.801 | 11.937 | 12.202 |

| calc. | 7.6455 | 7.9053 | 8.0377 | 8.3069 | 11.5478 | 11.8086 | 11.9411 | 12.2093 |

| PD (%) | 0.137 | 0.148 | 0.178 | 0.073 | 0.033 | 0.064 | 0.034 | 0.060 |

TABLE 5.

Experimental (exp.) and calculated (calc.) line positions in Tesla for the 170-GHz EPR spectrum at 17 and 35 K for the orientation of B perpendicular to the crystal c-axis.

| 17 K | 35 K | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| site a (B ⊥ c-axis) | ||||||||

| exp. | 5.898 | 6.020 | 6.0581 | 6.177 | 5.997 | 6.0396 | 6.170 | 6.214 |

| calc. | 5.8960 | 6.0117 | 6.0589 | 6.1767 | 5.9980 | 6.0390 | 6.1694 | 6.2157 |

| PD (%) | 0.034 | 0.138 | 0.013 | 0.005 | 0.017 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.027 |

| site b (B ⊥ c-axis) | ||||||||

| exp. | 5.525 | 5.701 | 6.312 | * | 5.8919 | 5.954 | 6.235 | 6.287 |

| calc. | 5.5217 | 5.7004 | 6.3124 | 6.4890 | 5.8918 | 5.9506 | 6.2325 | 6.2893 |

| PD (%) | 0.060 | 0.011 | 0.006 | - | 0.0017 | 0.057 | 0.040 | 0.037 |

The last line of site b could not be observed over the magnetic field range 5.2–6.6 T used for recording the spectrum at this temperature. PD (%) has been defined in the caption of Table 2.

Acknowledgments

S.K. Misra is grateful to NSERC (Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada) for partial financial support, as well as to NHMFL for a Visiting Scientist’s award, to carry out this project in Tallahassee, Florida. J.H. Freed and D. Tipikin acknowledge financial support from NIH/NCRR Grant P41RR016292, USA. Some EPR measurements in this study were performed at the NHMFL, with the kind assistance of Dr. Andrew Ozorowski, which is funded by the NSF through the Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-0654118, the State of Florida and the DOE.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Knapp MJ, Krzystek J, Brunel LC, Hendrickson DN. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:281. doi: 10.1021/ic9910054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Telser J, van Slageren J, Vongtragool S, Dressel M, Reiff WM, Zvyagin SA, Ozarowski A, Krzystek J. Magn Reson Chem. 2005;43:130. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozarowski A, Zvyagin SA, Reiff WM, Telser J, Brunel L-C, Krzystek J. JACS Communic. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krzystek J, Zvyagin SA, Ozarowski A, Trofimenko S, Telser J. J Magn Reson. 2006;178:174. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krzystek J, Ozarowski A, Tofimenko S, Zvyagin SA, Telser J. Slov Tech Univ. Bratislava: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knapp MJ, Krzystek J, Brunel LC, Hendrickson DN. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:3321. doi: 10.1021/ic9901012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carver G, Dobe C, Jensen TB, Tregenna-Piggott PLW, Janssen S, Bill E, McIntyre GJ, Barra A. Inorg Chem. 2006;45(12):4695. doi: 10.1021/ic0601889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Earle KA, Hofbauer W, Dzikovski B, Moscicki JK, Freed JH. Magn Res In Chemistry. 2005;43:5256–5266. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Portis AM. Phys Rev. 1955;100:1219–1221. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Portis AM. Technical Note No. 1. Sarah Mellon Scaife Radiation Laboratory, University of Pittsburgh; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chemerisov SD, Tipikin DS, Grinberg OYa, Lebedev YaS. Russ J Phys Chem. 1993;67:2220. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray S, Zalkin A, Templeton DH. Acta Cryst B. 1973;29:2741. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abragam A, Bleaneys B. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance of Transition Ions. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1970. p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Misra SK. In: Handbook on Electron Spin Resonance. Poole CP Jr, Farach HA, editors. Vol. 2. American Institute of Physics; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.This program was obtained from A. Ozarowski in the form of an a.exe file, private communication (2006).

- 16.Misra SK. Physica B. 1994;194:193. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Misra SK. Physica B. 1997;240:183. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krzystek J, Ozarowski A, Telser J. Coord Chem Rev. 2006;250:2308. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubins RS. Proc Phys Soc. 1962;80:244. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Champion PM, Sievers AJ. J Chem Phys. 1977;66:1819. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palumbo D. Nuovo Cim. 1958;8:271. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yi-Yang Z, Min-Guang Z. J Phys C: Solid State Physics. 1987;20:5097. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ham FS. Jahn-Teller effects in electron paramagnetic resonance spectra. In: Geschwind S, editor. Electron paramagnetic resonance. Pleum Publishing Corp; new York: 1961. [Google Scholar]