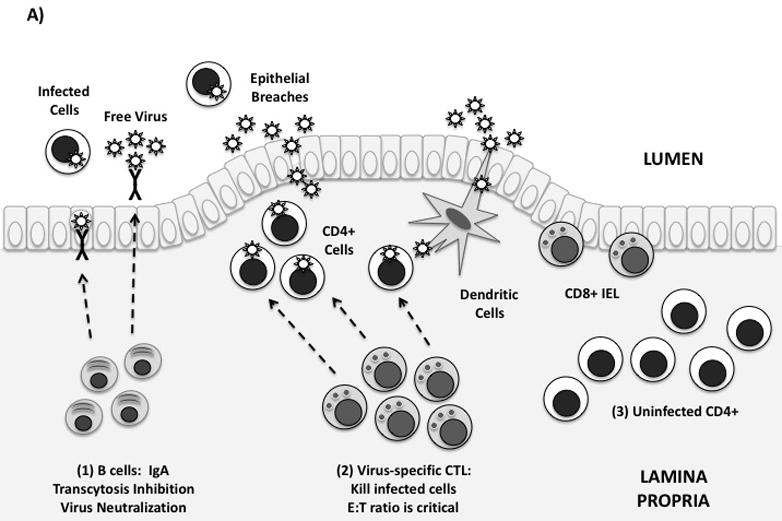

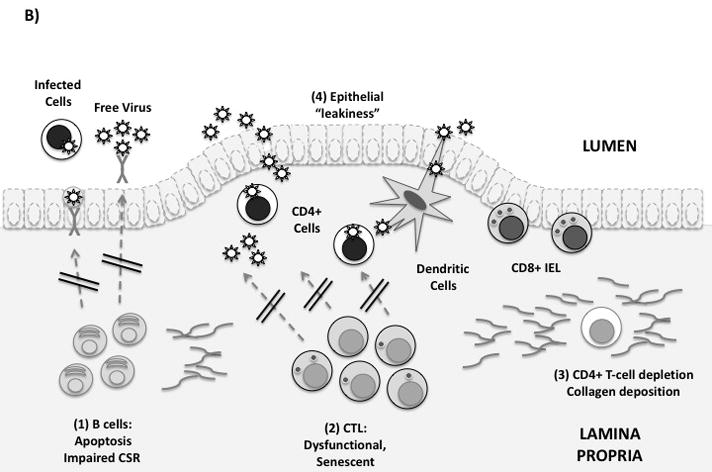

Figure 1. Immune defenses in the gastrointestinal mucosa.

(A) Idealized mucosal defenses. Virus may enter the gut through transcytosis, direct entry via epithelial breaches, or by binding to dendritic cells. Immune defenses in the lamina propria are shown from left to right: (1) Mucosal antibodies are secreted by plasma cells in the lamina propria. IgA dimers are taken up by epithelial cells and secreted into the GI lumen. Mucosal IgA may block infection by binding and neutralizing free virus, infected cells, and/or by blocking transcytosis of virus by epithelial cells. (2) Virus-specific CTL can kill infected cells by granule exocytosis. “Polyfunctional” CTL also secrete multiple cytokines and chemokines. In order to adequately control infection, a high in vivo E:T ratio is required. (3) Uninfected CD4+ T-cells are abundant in the intestinal lamina propria, and are exquisitely sensitive to HIV infection. Th17 cells may be preferentially infected and depleted.

(B) Mucosal immune defenses are impaired in HIV infection. From left to right: (1) Mucosal B-cell function is affected by disruption of Peyer’s patches, induction of T/B-cell apoptosis, and by direct effects of Nef on class switching. (2) Mucosal CTL express low levels of perforin and high levels of PD-1. Free E-cadherin may ligate KLRG-1, inhibiting CTL function. (3) Lamina propria CD4+ T-cells, including Th17 cells, are rapidly infected and depleted. Collagen fibrosis impairs their reconstitution following antiretroviral therapy. (4) Local production of proinflammatory cytokines and loss of the Th17/Treg balance leads to increased epithelial permeability to microbial products. This may contribute to systemic immune activation.