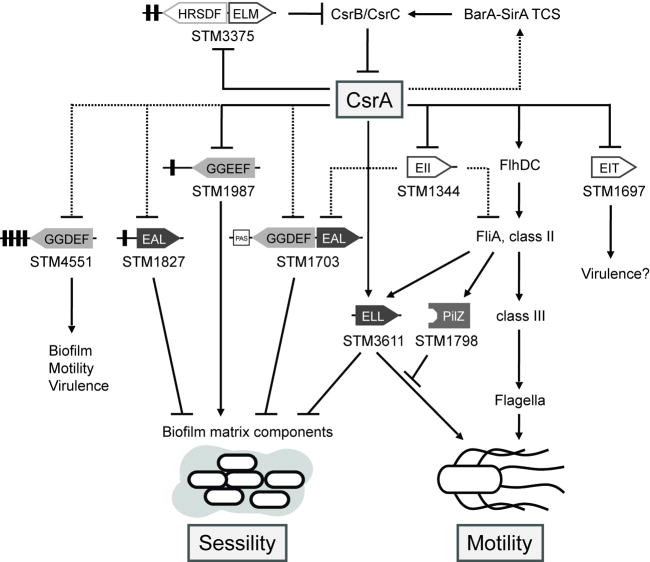

Figure 6.

Schematic model illustrating the interplay between the Csr-, the c-di-GMP and the flagella regulatory system in Salmonella Typhimurium. Apparent direct (solid line) and indirect (dashed line) roles of CsrA in the expression of genes encoding GGDEF and EAL domain proteins resulting in the tight control of the sessility-motility switch in S. Typhimurium. STM4551 and STM1987 possess DGC activity (Garcia et al., 2004; Solano et al., 2009), whereas STM1703, STM1827 and STM3611 act as PDEs (Simm et al., 2004; Simm et al., 2007). The c-di-GMP metabolizing activities of these proteins control phenotypes in motility, biofilm formation or viruence. In contrast, STM1344, STM3375 and possibly STM1697 contain degenerate EAL/GGDEF domains (unshaded), which cannot synthesize or degrade c-di-GMP, but have apparently evolved alternative functions, e.g. regulatory functions (Simm et al., 2009). Notably, CsrA controls the flagella cascade at multiple levels in the hierarchy: by apparent direct regulation of the flagella master regulator FlhDC and STM1344, which influences the flagella cascade upstream of fliA, and by apparent direct and indirect regulation of STM3611. Presumably, this multi-layer control allows CsrA to coordinate flagella synthesis with motor function. By regulating STM3375 (CsrD), which, along with RNase E, destabilizes the CsrB and CsrC sRNAs in E. coli (Suzuki et al., 2006), CsrA seems to control its own activity by an autoregulatory loop. CsrB and CsrC are positively controlled by the two-component system (TCS) BarA-SirA (Altier et al., 2000b; Teplitski et al., 2003), which allows the integration of environmental signals into the regulatory network. In E. coli (Gudapaty et al., 2001) and in S. Typhimurium (our unpublished observations) transcription of csrB and csrC also requires upstream activation by CsrA, probably through the BarA-UvrY (BarA-SirA) TCS (Suzuki et al., 2002), indicative of an additional feedback loop.