Abstract

Ad.Egr-TNF is a radioinducible adenovector currently in phase 3 trials for inoperable pancreatic cancer. The combination of Ad.Egr-TNF and ionizing radiation (IR) contributes to local tumor control through the production of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) in the tumor microenvironment. Moreover, clinical and preclinical studies with Ad.Egr-TNF/IR have suggested that this local approach suppresses the growth of distant metastatic disease; however, the mechanisms responsible for this effect remain unclear. These studies have been performed in wild-type (WT) and TNFR1,2−/− mice to assess the role of TNFα-induced signaling in the suppression of draining lymph node (DLN) metastases. The results demonstrate that production of TNFα in the tumor microenvironment induces expression of interferon (IFNβ). In turn, IFNβ stimulates the production of chemokines that recruit CD8+ T cells to the tumor. The results further demonstrate that activation of tumor antigen–specific CD8+ CTLs contributes to local antitumor activity and suppression of DLN metastases. These findings support a model in which treatment of tumors with Ad.Egr-TNF and IR is mediated by local and distant immune-mediated antitumor effects that suppress the development of metastases.

Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) is a cytokine, initially named for its induction of hemorrhagic necrosis in murine tumors, has been identified as a mediator of a broad range of biological actions, including innate and adaptive immunity. As an effector molecule of macrophage and CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL)–mediated tumor cell killing, production of TNFα by CTLs was reported to be crucial for the elimination of established tumors, including antigen-loss variants, by destroying bone marrow (BM)- and non-BM-derived tumor-associated stromal cells.1 The interaction of host-derived TNFα with TNFR1 induces maturation of antigen-presenting cells, thereby enhancing the efficacy of antigen presentation within tumor draining lymph nodes (DLNs). The improved antigen presentation stimulates tumor antigen–specific CD8+ T-cell activation and proliferation. Moreover, activation of TNFR2 on CD8+ T cells sustains the early proliferative phase of tumor antigen–specific CD8+ T cells in tumor DLNs.2

TNFα-induced autocrine/paracrine signaling in macrophages mediates low and sustained production of type I interferon (IFNα/β), which activate interferon-response genes and other inflammatory molecules.3 IFNα/β production by both dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages are pivotal in innate and adaptive immune responses to adenovirus, and contribute to the antitumor effect of adenoviral vectors delivering gene therapy.4,5,6 In addition to their well-known antiviral actions, IFNα/β have effects on cellular growth, and metabolism and have utility as antitumor agents in melanoma and leukemia. Expression of IFNα/β has been identified in the cross-priming of CD8+ T cells during viral infections.7,8 In CD8+ T cells receiving appropriate T-cell receptor and co-stimulatory signals, IFNα/β signaling is essential for the expansion and differentiation of antigen-specific effector CTLs.8 IFNα/β also contribute to the CD8+ CTL response by inducing diverse chemokines that recruit CTLs to the site of infection and cytokine production.8

The antitumor effects of ionizing radiation (IR) have recently been linked to the proliferation and infiltration of CD8+ T cells, and increased antigen presentation in DLNs.9,10,11 Tumor cell death induced by IR activates several danger signals, which promote a DC-mediated CD8+ CTL response that confers antitumor immunity.12,13,14,15 Local IR-induced killing of tumor cells can result in high levels of antigen release, which can further sensitize tumor stroma to CTL-mediated destruction.16,17 In addition, IR increases the production of endogenous and radiation-induced antigenic peptides and increases major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and MHC class II presentation of these peptides.18,19,20,21 Local IR also changes the tumor microenvironment, increases IFNγ and chemokine expression, and thereby promotes effective CTL trafficking into irradiated tumors.10,22,23

Systemic delivery of the TNFα protein for cancer treatment has had limited success because of severe dose-limiting toxicities. Several strategies have been employed to overcome the side effects. One strategy has been an adenoviral-mediated gene delivery approach, whereby a radiation-inducible promoter controls expression of the TNFα gene (Ad.Egr-TNF) in the irradiated tumor. The combination of IR and Ad-Egr-TNF gene therapy produced striking antitumor effects in animal systems and Ad.Egr-TNF (TNFerade; GenVec, Gaithersburg, MD) has been investigated in phase 1 and 2 clinical trials with encouraging results.24,25 TNFerade is currently in a phase 3 trial for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. The preliminary results of this trial have identified a subset of longer term survivors, supporting the hypothesis that certain patients may benefit from a “vaccine-like” effect whereby the local induction of TNFα induces antitumor immunity.26,27 The effectiveness of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR is mediated by (i) the local synergistic effects of TNFα production in combination with IR; and (ii) suppression of DLN metastases via undefined host mechanisms.27,28 Here, we show that Ad.Egr-TNF/IR mediates suppression of both local tumors and DLN metastases, at least in large part, through activation of the adaptive immune system.

Results

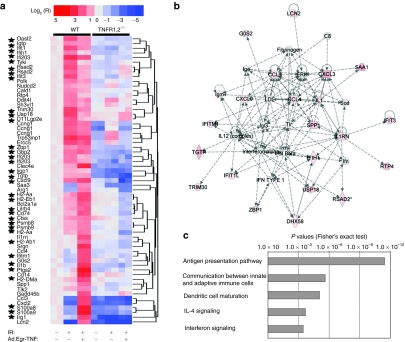

Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment induce an IFN response that is dependent on intact TNFα signaling in the host

B16F1 tumors were established in wild-type (WT) and TNFR1,2−/− mice to investigate the role of TNFα/TNFR1,2 signaling in Ad.Egr-TNF/IR-induced antitumor activity. RNA profiling of the tumors was performed with Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 GeneChips and analysis of DNA array data was based on techniques used in our previous work.29,30 A total of 478 genes was selected based on the pair-wise comparisons of B16F1 tumors grown in WT and TNFR1,2−/− mice and treated under identical experimental conditions. Using unsupervised hierarchical clustering, we selected a group of genes predominantly upregulated in response to Ad.Egr-TNF/IR in tumors grown in WT, but not in the TNFR1,2−/−, mice (Figure 1a). Primary investigation of this cluster revealed that 35 out of 61 (57.4%) probe sets represented IFN-stimulated genes or genes involved in the regulation of the IFN response (Supplementary Table S1). Overall expressional scores of the IFN pathway for B16F1/WT and B16F1/TNFR1,2−/− tumors were 0.911 ± 0.066 and 0.697 ± 0.059, respectively (P < 0.001). For an in-depth analysis of functions associated with genes presented in Figure 1a and Supplementary Table S1, we used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. The two most significant networks of genes and corresponding protein interactions were involved in immune cell trafficking (2.00 × 10−11 < P < 0.00064, Fisher's exact test) and antigen presentation (2.43 × 10−10 < P < 0.00048). Importantly, in the network of immune cell trafficking, the central node was associated with IFNα/β (Figure 1b). Among the most significant biological functions, we identified cell-to-cell signaling and interaction (5.69 × 10−13 < P < 0.003) and the inflammatory response (2.33 × 10−11 < P < 0.0039). Consistent with these observations, the top five canonical pathways were identified as antigen presentation, communication between innate and adaptive immune cells, DC maturation, interleukin (IL)-4 signaling, and IFN-signaling (Figure 1c; x axis represents significance score for each pathway). Among specific genes involved in these processes and differentially expressed in response to Ad.Egr-TNF/IR in B16F1/WT, but not in B16F1/TNFR1,2−/−, tumors, we identified (i) different members of MHC class II molecules (H2-Aa, H2-Ab1, H2-DMa, H2-Eb1, and its related CD74), (ii) the macrophage and immature DC marker CD14, (iii) components of proteosomes, (iv) effectors involved in antigen processing (LMP7 and LMP2), (v) IFN-inducible RNA-helicase MDA5 (IFIH1), and (vi) LGP2 (DHX58)-members of RIG1-like receptors involved in RNA recognition and induction of IFN type I signaling and inflammatory cytokine/chemokine production. Furthermore, among these genes is Zbp1 (DAI), which acts as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor that can activate type I interferon and is produced by tumor-associated macrophages (TAMφ).

Figure 1.

IFN response and immune activation following Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment is TNFα-signaling dependent. B16F1 tumors were grown in WT C57/Bl6 mice or in TNFR1,2−/− mice. Tumors were irradiated or treated with Ad.Egr-TNF in combination with ionizing radiation (IR) as described in the Materials and Methods. Purification of RNA, hybridization with arrays (Mouse Genome 430 2.0 GeneChips; Affymetrix) and data analysis are described in the Materials and Methods. Expression values were normalized to untreated control tumors grown in WT mice. Stars indicate genes activated by type I and type II IFNs. (a) Two-dimensional unsupervised hierarchical clustering of genes upregulated in B16F1/WT, but not in B16F1/TNFR1,2−/− tumors. Genes were annotated according to Affymetrix Netaffix database (see Supplementary Table S1). The legend for expressional values is shown in heatmap. (b) Web of interaction of genes and their protein products presented in a. The network represents immune cell trafficking. Red color is proportional to the upregulation of any given gene in B16F1/WT relative to B16F1/TNFR1,2−/− tumors. Note that the central node is represented by IFNα/β. (c) The top five canonical pathways associated with genes presented in a. The five pathways are associated with immune function and include communication between innate and adaptive immune cells and IFN signaling. Network and pathway data were obtained with Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software. P values indicate significance of differences between expression of the given pathway in B16F1/WT relative to B16F1/TNFR1,2−/− tumors. IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; WT, wild type.

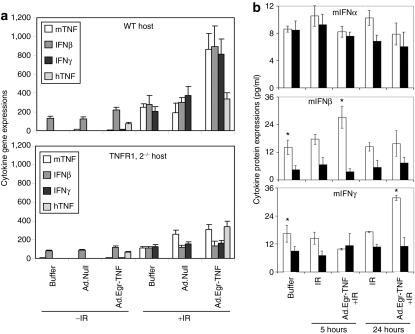

As this TNFα-dependent type I IFN signaling was identified as the most significant gene family by DNA arrays, we quantified IFN gene and protein expression in B16.SIY tumors grown in the WT and TNFR1,2−/− hosts (Figure 2). Reverse transcriptase-PCR showed that human TNFα (hTNFα) gene transcripts were comparable in tumors grown in WT and TNFR1,2−/− mice, and were increased by IR, consistent with control by a radio-inducible promoter. Higher levels of murine TNFα gene induction were detected in tumors grown in both WT and TNFR1,2−/− mice after IR as compared with controls. However, IFNβ gene transcripts were upregulated only in tumors grown in WT mice treated with Ad.Egr-TNF/IR, demonstrating that intact TNFα/TNFR1,2 signaling is necessary for IFNβ upregulation. IFNγ gene expression was also increased in tumors grown in WT hosts (Figure 2a). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay demonstrated that baseline production of IFNα is identical in B16F1 tumors grown in WT and TNFR1,2−/− mice (Figure 2b). However, basal production of IFNβ was 3.13 higher in tumors grown in WT mice as compared to tumors grown in TNFR1,2−/− mice (P = 0.012). IFNβ production 5 hours after Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment was increased 1.9-fold in tumors grown in WT mice as compared to controls (P = 0.052), and was 7.6-fold higher than IFNβ production in tumors grown in TNFR−/− mice (P = 0.032). IFNγ production 24 hours after Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment was upregulated 1.9-fold relative to control tumors grown in WT mice (P = 0.038), although no significant upregulation of IFNγ was detected in Ad.Egr-TNF/IR-treated tumors grown in TNFR1,2−/− mice. These findings indicate that TNFα signaling in the tumor microenvironment is necessary for induction of IFN expression in the response to Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment.

Figure 2.

Transcriptional and translational synthesis of IFNs in response to Ad.Egr-TNF/IR requires host TNFα/TNFR1,2. (a) Reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis revealed higher levels of mTNFα/IFNβ/γ gene expression in Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treated B16.SIY tumors relative to untreated control tumors in WT and TNFR1,2−/− mice. (b) Levels of IFNα, IFNβ, and IFNγ were measured in B16F1/WT and B16F1/TNFR1,2−/− tumors using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. All measurements were done 5 and 24 hours after IR when 32 and 48 hours after the 1st Ad.Egr-TNF treatments. Open bars indicate tumors grown in WT mice and solid bars indicate tumors grown in TNFR1,2−/− mice. *P < 0.05, Student's two-tailed t-test, indicate significance of differences between tumors grown in WT and TNFR1,2−/− mice. IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; mTNF, murine tumor necrosis factor; WT, wild type.

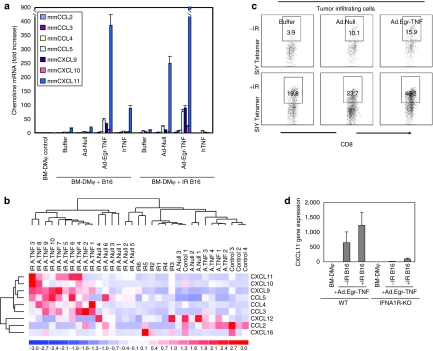

Ad.Egr-TNF/IR increase chemokine production in BM-DMφ/TAMφ and induce CD8+ T-cell infiltration in B16.SIY tumors

As presented in Figure 1a, several chemokines were upregulated following treatment of mice with intact TNFα/TNFR1,2 signaling with Ad.Egr-TNF/IR. Chemokines are necessary for CD8+ T-cell migration and infiltration in the tumor microenvironment.31,32,33 We cocultured BM-DMφ with irradiated (10 Gy) or unirradiated B16.SIY tumor cells that had been also treated with Ad.Egr-TNF, Ad.Null, or rhTNFα. Reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis demonstrated the induction of chemokines reported to be important for CD8+ cell chemotaxis and tumor infiltration, including CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, CXCL12, and CXCL16. Compared to control, BM-DMφ cocultured with both irradiated and unirradiated B16.SIY tumor cells showed increased CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 expression. Compared to Ad.Null, Ad.Egr-TNF enhanced CCL5 induction by 11-fold and CXCL11 by 20-fold when cocultured with unirradiated B16.SIY tumor cells. Moreover, CCL5 was enhanced threefold and CXCL11 by fourfold when cocultured with irradiated B16.SIY tumor cells (Figure 3a). Compared to rhTNFα, Ad.Egr-TNF significantly enhanced CCL5 expression by sevenfold and CXCL11 by fourfold when cocultured with unirradiated B16.SIY tumor cells, and enhanced CCL5 by 12-fold, CXCL11 by 900-fold when cocultured with irradiated B16.SIY tumor cells. Compared to unirradiated B16.SIY tumor cells, irradiated B16.SIY tumor cells also stimulated higher levels of CCL5 (sevenfold) and CXCL11 (200-fold) expression in the presence of Ad.Egr-TNF. These results demonstrate that irradiated B16.SIY tumor cells induce enhanced chemokine expression by BM-DMφ (TAMφ), which represent a major component of stroma in B16 tumor microenvironment. Reverse transcriptase-PCR was performed using B16.SIY tumor samples collected from WT mice, and a heatmap demonstrated that, in Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treated tumors, chemokines CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 were upregulated, but not CCL2, CXCL12, or CXCL16 (Figure 3b). Ad.Egr-TNF/IR strongly enhanced chemokine expression in the WT tumor microenvironment, which was correlated with increased tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell infiltration (Figure 3c). To confirm that IFNα/β signaling is necessary for TNFa-induced chemokine production, studies were also performed in IFNA1R−/− mice. Significantly, induction of CXCL11 was substantially decreased when Ad.Egr-TNF treated BM-DMφ generated from IFNA1R−/− mice when cocultured with either irradiated or unirradiated B16.SIY tumor cells (Figure 3d). These results demonstrated the importance of intact host TNFα/TNFR1,2 and IFNβ/IFNAR signaling for Ad.Egr-TNF/IR-induced chemokine production and, in turn, an antitumor CD8+ CTL infiltration.

Figure 3.

Induction of chemokines in Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treated tumors resulted in greater numbers of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells infiltration. (a) Ad.Egr-TNF/IR enhances chemokine production in BM-DMφ. BM-DMφ were incubated with Ad.Egr-TNF, Ad.Null, or rhTNFα, rmTNF and cocultured with 10 Gy irradiated or unirradiated B16.SIY tumor cells in a transwell system for 6 hours. BM-DMφ were collected, total RNA extracted, and reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR performed to analyze the relative expression level of chemokines. Data shown are the mean ± SD of duplicate samples of one experiment which represents four individual experiments with similar results. BM-DMφ monoculture served as control. (b) Groups of chemokine gene transcripts were detected at a relatively higher level in Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treated WT tumors. WT C57BL/6 mice (n = 6/group) were subcutaneously injected with 5 × 105 B16.SIY melanoma cells, Ad.Egr-TNF (2 × 109 particle units) and control Ad.Null (2 x 109 vector particles) virus were injected intratumorally on day 9 and day 10. A radiation dose of 20 Gy was locally delivered on day 10. At 7 days after IR, tumors were harvested, 1/3 of each tumor was lysed in Trizol, total RNA was purified, and multiple chemokine gene transcripts were detected by RT-PCR and normalized to GAPDH. (c) More SIY antigen–specific CD8+ T-cell infiltration in Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treated WT tumors. Experiments performed as above, 1/3 of tumors were digested into single-cell suspension, stained with SIY tetramer, and anti-CD8 antibody to analyze frequency of CD8+ TIL. Gated on CD8+ cells, SIY/Kb PE tetramer–positive cells are shown. BM, bone marrow; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; rhTNF, recombinant human tumor necrosis factor; WT, wild type.

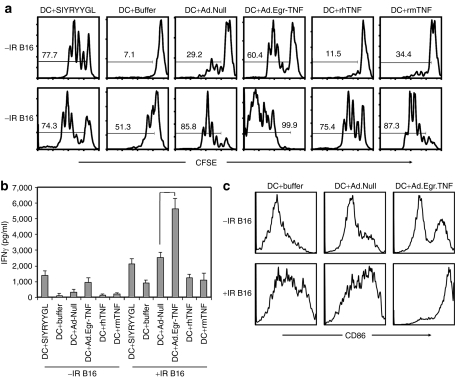

Exposure of BM-DC to Ad.Egr-TNF/IR mediates CD8+ T-cell activation and proliferation

In concert with the IFNβ response in mice with intact TNFα/TNFR1,2 signaling, several MHC class II and class I genes, which play important roles in antigen-presenting cell function, were upregulated following treatment with Ad.Egr-TNF/IR. To determine whether BM-DC that proliferated and matured following Ad.Egr-TNF treatment stimulate CD8+ T-cell proliferation, we cocultured carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)–labeled splenic CD8+ T cells with BM-DC treated with Ad.Egr-TNF or Ad.Null in the presence of CD4+ T cells and irradiated (10 Gy) or unirradiated B16.SIY tumor cells. Exogeneous soluble model tumor SIY antigen plus 20 U recombinant IL-2 served as a positive control. By analyzing CFSE dilutions and measuring IFNγ production, we observed that Ad.Egr-TNF pretreated BM-DC stimulate CD8+ cell activation and proliferation when cocultured with B16.SIY tumor cells. These effects were greater than additive when the identical experiment was performed with Ad.Null, human TNFα, or murine TNFα treated BM-DC. CD8+ cells proliferated in response to Ad.Egr-TNF pretreated BM-DC when cocultured in the presence of irradiated B16.SIY tumor cells. This effect was greater than in similarly treated cultures with unirradiated tumor cells (Figure 4a). IFNγ production was also significantly higher in cocultures of CD8+ cells and BM-DC pretreated with Ad.Egr-TNF, as compared to Ad.Null, and cultured in the presence of irradiated B16.SIY tumor cells (Figure 4b; P = 0.014). To investigate the mechanism of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR enhanced proliferation and IFNγ-induced Ag-specific CD8+ T cells following IR, we tested the hypothesis that Ad.Egr-TNF stimulates BM-DC maturation. We confirmed that Ad.Egr-TNF stimulates BM-DC maturation in the presence of irradiated B16.SIY cells by increased CD86 expression (Figure 4c). These results demonstrate that DC in the tumor microenvironment post-treatment with Ad.Egr-TNF/IR, likely engulf virus and antigens from dying tumor cells, mature and efficiently prime CD8+ cell proliferation and function in the DLNs and/or tumor microenvironment.

Figure 4.

Ad.Egr-TNF/IR promote priming of Ag-specific CD8+ T-cell proliferation and greater IFNγ production than either Ad.Null or rhTNFα and rmTNF alone. (a) Ad.Egr-TNF enhanced proliferation of CD8+ T cells in the presence of 10 Gy irradiated or unirradiated or B16.SIY tumor cells. Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)–labeled splenic CD8+ cells were cocultured with BM-DC treated with Ad.Egr-TNF control Ad.Null vectors, in the presence of irradiated (10 Gy) or unirradiated B16.SIY tumor cells, model tumor antigen SIY plus 20 U rIL-2 as a positive control. The same number of CD4+ T cells were added as described in the Materials and Methods. (b) Ad.Egr-TNF enhanced the IFNγ production of CD8+ T cells in the presence of 10 Gy irradiated or unirradiated B16.SIY tumor cells. Coculture supernatant was collected from the above experiments and IFNγ production was analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data are shown as the mean ± SD of duplicate samples and are representative of three separate experiments. (c) Ad.Egr-TNF promoted BM-DC maturation in the presence of 10 Gy irradiated or unirradiated B16.SIY tumor cells. Ad.Egr-TNF or control vectors were added to BM-DC at 7 day of induction in the presence of 10 Gy irradiated or unirradiated B16.SIY tumor cells. After 24 hours, BM-DC was analyzed for CD86 expression by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. BM, bone marrow; DC, dendritic cells; IFN, interferon; rIL, recombinant interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Ad.Egr-TNF/IR suppresses primary tumor growth and DLN metastases

To determine whether Ad.Egr-TNF/IR enhanced CD8+ T-cell proliferation is sufficient to confer control of local tumor growth and prevent DLN metastases in vivo, B16.SIY tumor cells were injected into WT mice. When tumors reached 100–200 mm3, Ad.Egr-TNF or Ad.Null were injected intratumorally on two consecutive days and the tumors were treated with 20 Gy IR. Ad.Egr-TNF significantly enhanced the antitumor effects of IR as determined by tumor volumes at day 30 compared to that found with Ad.Null/IR treatment (219 ± 43 mm3 versus 2,319 ± 461 mm3, day 30, P = 0.026) (Figure 5a). To test whether Ad.Egr-TNF/IR suppresses DLN metastases, tumor-bearing mice were treated with Ad.Egr-TNF and 20Gy IR, excluding DLNs from the radiation field. The primary tumors were surgically removed 5 days after IR when the tumor volumes were similar (IR 130 ± 27 mm3 versus control 109 ± 25 mm3, P = 0.108) to exclude the influence of primary tumor cells that continue to metastasize to DLNs. At 35 days after tumor inoculation, the DLNs were collected. Metastatic colonies in the DLNs were detected in Ad.Null/IR and control groups. Notably, Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment significantly reduced the number of metastatic colonies in DLNs (Figure 5b, P = 0.047).

Figure 5.

Ad.Egr-TNF/IR inhibit local tumor growth and DLN metastases and stimulate CD8+ T-cell proliferation. (a) Enhanced inhibition of local B16.SIY tumor growth following treatment with Ad.Egr-TNF/IR compared to IR alone, or Ad.Null/IR. WT C57BL/6 (n = 12/group) were subcutaneously injected with 5 × 105 B16.SIY melanoma cells, Ad.Egr-TNF [2 × 109 particle units (pu)] and control Ad.Null (2 × 109 pu) virus were intratumorally injected on day 9 and day 10. A radiation dose of 20 Gy was delivered on day 10. (b) The same experimental conditions noted above except the primary tumors were surgically removed 5 days after IR. Mice were killed on day 35 for DLN tumor clonogenic assay (n = 4–5/group). (c) 5 × 105 B16.SIY melanoma cells were injected subcutaneously. Virus and IR were administrated as above. On the same day of IR 5 × 106 carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)–labeled naive 2C T cells were transferred by intravenous injection. At 4 days after IR, DLNs were harvested and single-cell suspension were acquired, gating on CD8+ and 1B2+ cells, CFSE dilution of 2C T cells were analyzed. DLN, draining lymph node; IFN, interferon; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; WT, wild type.

To determine whether Ad.Egr-TNF/IR modify the radiation response associated with a CD8+ immune response in vivo, B16.SIY tumor-bearing mice were treated with 20 Gy IR and then injected intravenously with CFSE-labeled CD8+ 2C transgenic T-cells that specifically recognize the SIY tumor antigen. Four days postinjection, irradiated and nonirradiated tumor DLNs were harvested and CFSE+1B2+CD8+ cell proliferation was analyzed by CFSE dilution. Proliferation of 2C T-cells was induced by irradiated, as compared to unirradiated, tumor DLN cells (Figure 5c). Ad.Null/IR also induced greater proliferation of transferred Ag-specific naive T cells compared with untreated controls. Importantly, Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment dramatically enhanced the proliferation of Ag-specific 2C T cells (93% versus 65%, P = 0.005).

CD8+ depletion blocks the effect of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR on the primary tumor and DLN metastases

To investigate whether the enhanced proliferation of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells by Ad.Egr-TNF/IR is in part essential for its antitumor effects and suppression of DLN metastases, we depleted CD8+ T cells with an anti-CD8 depleting antibody. Depletion of CD8+ T cells partially blocked the effect of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR on local regrowth of B16.SIY tumors (Figure 6a). Moreover, depletion of CD8+ T cells almost completely reversed the antimetastatic effects of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment on B16.SIY metastases in DLNs. These effects were visualized by direct observation of the size and color of DLNs, and quantified by colony assays (Figure 6b,c; P = 0.003). Histological analysis of primary tumors further showed lymphocyte-sized inflammatory cells infiltrating tumors treated with Ad.Egr-TNF/IR (Supplementary Figure S1a). Histology of DLNs was also performed when the primary tumors were surgically removed 5 days after IR. The DLNs from Ad.Egr-TNF/IR-treated mice had a normal LN architecture and were free of metastatic tumor cells (Supplementary Figure S1b). To confirm these results, experiments were repeated in CD8+ knockout mice. In this model, the suppressive effect of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR on B16.SIY local tumor growth and DLN metastases was substantially reduced (Supplementary Figure S2). These results demonstrate that the effect of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR on both the local tumor and DLN metastases is dependent, at least in large part, on CD8+ T-cell function.

Figure 6.

Depletion of CD8+ T cells reversed the suppressive effects of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR on B16.SIY tumor growth and DLN metastasis. (a) B16.SIY tumor suppression after Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment is partially dependent on CD8+ T cells. WT C57BL/6 (n = 12/group) were subcutaneously injected with 5 × 105 B16.SIY melanoma cells, Ad.Egr-TNF [2 × 109 particle units (pu)] and control Ad.Null (2 × 109 pu) virus were injected intratumorally on day 9 and day 10. A radiation dose of 20 Gy was delivered locally on day 10. Mice were treated with CD8+-depleting antibodies before and after IR in addition to Ad.Egr-TNF/IR. (b,c) Depletion of CD8+ cells reverses the suppressive effect of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR on B16.SIY tumor regrowth and DLN metastases, Lymph node metastases was measured by direct observation of the size and color of DLNs, and by clonogenic assay of separated cells. (d) Schematic showing effects of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR on tumor microenvironment, the subsequent activation/proliferation and migration of CD8+ T cells. DLN, draining lymph node; IFN, interferon; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; WT, wild type.

Discussion

Our gene array analysis identified differential changes in functional immune molecules after Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment, which was dependent on intact TNFα/TNFR1,2 signaling and the production of IFNβ. The cellular communication in the tumor microenvironment is mediated by cross-talk between the innate and adaptive immune systems and is regulated by multiple signaling pathways. IFNβ, which is induced by Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment, plays an essential role in integrating the innate and adaptive immune responses.34 IFNβ is produced by either TAMφ and/or DC after engulfing double-stranded DNA from Ad. vectors and/or necrotic cells.35 Host cells are also the crucial targets of the antitumor activity of IFNα/β.36 Production of IFNγ by activated CD8+ T cells, as well as IFNα/β, can further upregulate MHC class I to sensitize irradiated tumor cells to CD8+ CTL-mediated lysis. These responses could thus convert a tumor tolerant microenvironment toward one that mediates tumor eradication. High expression of TNFα in CD8+ CTLs could also contribute to destruction of the tumor stroma.1 Our findings thus indicate that IFNβ is essential in orchestrating the induction of an immune response to Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment, conceivably through regulating the production of cytokines and chemokines in both tumor and stromal cells (Figure 6d).

After activation by antigen-presenting cells in DLNs, naive T cells undergo differentiation into effector cells and downregulate CCR7, while increasing expression of CXCR3, CXCR6, and CCR5. These changes in chemokine receptors can exclude CD8+ T cells from DLNs, but promote their recruitment to the tumor site.31,32,33 The expression of CXCL9/CXCL10/CXCL11 is regulated by IFNs and plays an important role in chemoattraction of activated CD8+ T cells into tumor sites during immunoediting and active immunotherapy.34,37 An intact IFN-signaling pathway and constitutive nuclear factor-κB activity stimulated by TNFα and IFNβ are required for the induction of CXCL9/CXCL10/CXCL11 and CCL5 expression in multiple cell types.3,38,39 The present results demonstrate that TNFα/IFNα/β signaling is critical for Ad.Egr-TNF/IR-mediated chemokine induction and CD8+ T-cell infiltration.35 Here, we show that Ad.Egr-TNF/IR upregulates multiple chemokines to attract activated CD8+ T cells into the post-IR tumor microenvironment and, in turn, confer killing of the residual irradiated tumor cells.

The present investigation in an immunocompetent animal model shows that the combination of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR has significant antitumor effects mediated by the immune system. There are several aspects of our study that are applicable to current cancer molecular therapy. In radiotherapy and surgery, the primary tumor and DLNs are frequently treated together. If antigen presentation and T-cell activation take place in the DLNs (Figure 6d), these factors should be taken into account and perhaps metachronous treatment of the primary tumor and DLNs should be considered rather than “en block” treatment. Also gene therapies and vaccines that increase activation of the immune system as a goal should be considered in the context of the roles of the IFN and TNF families of cytokines to maximize induction of an immunological response. Finally, the genetic background of the patient in terms of intact TNFα/IFN signaling may be an important determinant of response to radiotherapy. The longer term survivors in subsets of patients treated with Ad.Egr-TNF/IR in esophageal and pancreatic cancers support the notion that Ad.Egr-TNF/IR induces tumor cytoreduction and activates an antitumor immune response in these patients.27,40

In summary, our results demonstrate that Ad.Egr-TNF/IR increases DC cross-presentation of tumor antigen, and thereby boosts priming and infiltration of CD8+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment. These effects are critically dependent on the endogenous production of IFNβ through activation of the TNFα/TNFR1,2 signaling pathway. Our findings further support the indispensable role of DC stimulated CD8+ CTL activity in IR-mediated immune responses, providing critical new insights into the therapeutic effect of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR and indicate that this approach is both a local treatment for tumors and a tumor vaccine. Systemic administration of TNFerade (GenVec, Gaithersburg, MD) induced by chemotherapeutic agents has been difficult in targeting adenovectors to tumors. Chemo/radio-inducible TNFerade is likely to be used for tumors that can be injected locally. Elsewhere, DC incubated with TNFerade immunization in combination with chemo/radiotherapy could produce additional antitumor responses in patients with microscopic metastases. These findings thus support a novel combined treatment modality for cancer that can achieve local control and suppress the development of metastases by activating the antitumor immunity.27,41

Materials and Methods

Mouse strain and tumor cell lines. All mice were bred and maintained in the specific pathogen free facility at the University of Chicago. For all experiments, mice were used in accordance to the animal experimental guidelines set by the Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee. C57BL/6 WT and TNFR1,2−/− mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) at 6–7 weeks old. CD8-KO mice were from the Dr Fu lab. IFNA1R-KO mice were from the lab of Dr Chong. B16F1, and B16-SIY culture, and anti-2C TCR-biotin (1B2) antibody staining were described previously.11,42 Rat anti-mouse CD8 2.43.1-depleting antibody was generated in the Finch Monoclonal Antibody Facility of The University of Chicago. Systemic depletion was confirmed by peripheral blood fluorescence-activated cell sorting staining. The depleted CD8+ subset represented <0.5% of the total lymphocytes, while other subsets were normal. SIY/Kb PE tetramer was purchased from Beckman Coulter (Brea, CA). All other antibodies for fluorescence-activated cell sorting were purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA).

Tumor inoculation, treatments, and evaluation of metastases by clonogenic assay. B16.F1 or B16.SIY cells (5 × 105) were injected subcutaneously on the leg. Tumor size was measured by three orthogonal axes (a, b, and c) every 3–4 days. Tumor volumes were calculated as abc/2. The tumor lesions were injected with 2 × 109 virus particles of Ad.Egr-TNF or Ad.Egr-Null intratumorally once per day for 2 days. At 3 hours after the 2nd injection, 20 Gy was delivered. For the DLN metastases evaluation after treatments, please refer ref. 11. Individual colonies representing micrometastases were counted and compared after 7–10 days. Both primary tumors and DLNs were also fixed in 10% neutral formalin and embedded, serial sections were stained for regular histology (hematoxylin and eosin) and immunohistochemistry for specific cells including CD8+ T cells.

DNA array analysis. RNA was purified and hybridized with GeneChip Mouse Genome 230 2.0 Arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) as described.43 The selection and analysis of genes differentially expressed in B16F1 grown in WT and TNFR1,2−/− C57/Bl6 mice was based on our previously detailed approaches.29,30 Briefly, each array was hybridized with a pooled sample normalized to total RNA and consisting of RNA obtained from three independent tumors. After data retrieval, data were rescaled using “global median normalization” across the entire data set43 and filtrated using a multistep filtration method that involves the application of receiver operating characteristic analysis for the estimation of cutoff signal intensity values. Subsequent analysis was based on pair-wise comparisons using Significance Analysis of Microarrays version 3.0.44 Differentially expressed probe set IDs were selected using a 2.0-fold induction cutoff level with a Δ value selected to reduce False Discovery Ratio to 0. Selected probe set IDs were annotated and functionally designated using Netaffx analysis center (https://www.affymetrix.com/analysis/netaffx/index.affx) and Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA). Matching of data sets, clustering and visualization of data were performed using JMP 7.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Adoptive transfer of T cells and fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. A total of 5 × 106 2C cells were labeled with CFSE then adoptively transferred (intravenously) into B16.SIY tumor bearing C57BL/6 mice as described and analyzed previously.11

Reverse transcriptase-PCR. Cells and tumors were homogenized in 1 ml Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and RNA was extracted following the manufacturer's protocol. Two micrograms of total RNA was subjected to DNAse treatment using Invitrogen's Amplification Grade DNAse I Kit. Complementary DNA was synthesized from one-half of the DNAse treated RNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative PCR was performed on an ABI 7900HT (Applied Biosystems) using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in a 10 µl reaction volume containing 3 µl of 1:40 diluted complementary DNA and 0.5 µl of 100 µmol/l primers. Changes in gene expression were calculated using the comparative Ct values with GAPDH as the endogenous gene control. ΔCt was calculated and relative expression of each cytokine/chemokine was compared and heatmap was generated by unsupervised gene clustering using Dchip software (Computational Genomics, Boston, MA). PCR primer sequences were obtained from qPrimerDepot at http://mouseprimerdepot.nci.nih.gov (Supplementary Table S2).

Statistical analysis. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-test was performed using GraphPad InStat, version 3.05 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) to compare the tumor volume averages of different experimental groups. Two-tailed Student's test were performed to compare means of different treatment groups. P < 0.05 was accepted for significance.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, generation of BM-DMφ, BM-DC, selection of CD8+ T cells, Ad.Egr-TNF infection, and cocluture with irradiated tumors cells in a transwell system are described in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALFigure S1. Histology of primary tumors and DLNs after Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment. a. Histology of primary tumors. Histology of primary tumors also showed the massive lymphocyte sized inflammatory cells infiltrating in tumors received Ad.Egr-TNF /IR treatment. WT C57BL/6 (n=12/group) were s.c injected with 5x105 B16.SIY melanoma cells, Ad.Egr-TNF (2x109pu) and control Ad.Egr-Null (2x109pu) virus were intratumorally injected on day 9 and day 10. 20 Gy was delivered on day 10. Tumors were harvested on 7 days post IR. b. Histology of DLNs from same experiments as above only the primary tumors were surgically removed 5 days post IR. Mice were sacrificed and DLNs were collected on day 35. Arrows marked at the margin of metastatic tumor cells.Figure S2. Small effect of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR on B16.SIY primary tumor regrowth and DLN metastases in CD8 knockout mice. a. CD8 knockout mice with C57BL/6 background (n=12/group) were s.c injected with 5x105 B16.SIY melanoma cells, Ad.Egr-TNF (2x109pu) and control Ad.Null (2x109pu) virus were injected intratumorally on day 9 and day 10. 20 Gy was delivered locally on day 10. b. Small effect of Ad.Egr-TNF /IR on B16.SIY tumor DLN metastases, Lymph node metastases was measured by clonogenic assay.Table S1. Gene symbol and abbreviations.Table S2. Primer sequences.Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Histology of primary tumors and DLNs after Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment. a. Histology of primary tumors. Histology of primary tumors also showed the massive lymphocyte sized inflammatory cells infiltrating in tumors received Ad.Egr-TNF /IR treatment. WT C57BL/6 (n=12/group) were s.c injected with 5x105 B16.SIY melanoma cells, Ad.Egr-TNF (2x109pu) and control Ad.Egr-Null (2x109pu) virus were intratumorally injected on day 9 and day 10. 20 Gy was delivered on day 10. Tumors were harvested on 7 days post IR. b. Histology of DLNs from same experiments as above only the primary tumors were surgically removed 5 days post IR. Mice were sacrificed and DLNs were collected on day 35. Arrows marked at the margin of metastatic tumor cells.

Small effect of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR on B16.SIY primary tumor regrowth and DLN metastases in CD8 knockout mice. a. CD8 knockout mice with C57BL/6 background (n=12/group) were s.c injected with 5x105 B16.SIY melanoma cells, Ad.Egr-TNF (2x109pu) and control Ad.Null (2x109pu) virus were injected intratumorally on day 9 and day 10. 20 Gy was delivered locally on day 10. b. Small effect of Ad.Egr-TNF /IR on B16.SIY tumor DLN metastases, Lymph node metastases was measured by clonogenic assay.

Gene symbol and abbreviations.

Primer sequences.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by grant RO-1 CA111423 from the NCI (RRW), Prostate Cancer Spore P50 CA090386, The Center for Radiation Therapy, The Ludwig Foundation, and a generous gift from the Foglia Family. R.R.W. and D.W.K. have stock in and are consultants to GenVec.

REFERENCES

- Zhang B, Karrison T, Rowley DA., and , Schreiber H. IFN-γ- and TNF-dependent bystander eradication of antigen-loss variants in established mouse cancers. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1398–1404. doi: 10.1172/JCI33522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzascia T, Pellegrini M, Hall H, Sabbagh L, Ono N, Elford AR, et al. TNF-α is critical for antitumor but not antiviral T cell immunity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3833–3845. doi: 10.1172/JCI32567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarilina A, Park-Min KH, Antoniv T, Hu X., and , Ivashkiv LB. TNF activates an IRF1-dependent autocrine loop leading to sustained expression of chemokines and STAT1-dependent type I interferon-response genes. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:378–387. doi: 10.1038/ni1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urosevic M, Fujii K, Calmels B, Laine E, Kobert N, Acres B, et al. Type I IFN innate immune response to adenovirus-mediated IFN-γ gene transfer contributes to the regression of cutaneous lymphomas. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2834–2846. doi: 10.1172/JCI32077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Huang X., and , Yang Y. Innate immune response to adenoviral vectors is mediated by both Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent pathways. J Virol. 2007;81:3170–3180. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02192-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fejer G, Drechsel L, Liese J, Schleicher U, Ruzsics Z, Imelli N, et al. Key role of splenic myeloid DCs in the IFN-αβ response to adenoviruses in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000208. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bon A, Etchart N, Rossmann C, Ashton M, Hou S, Gewert D, et al. Cross-priming of CD8+ T cells stimulated by virus-induced type I interferon. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1009–1015. doi: 10.1038/ni978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetson DB., and , Medzhitov R. Type I interferons in host defense. Immunity. 2006;25:373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugade AA, Moran JP, Gerber SA, Rose RC, Frelinger JG., and , Lord EM. Local radiation therapy of B16 melanoma tumors increases the generation of tumor antigen-specific effector cells that traffic to the tumor. J Immunol. 2005;174:7516–7523. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugade AA, Sorensen EW, Gerber SA, Moran JP, Frelinger JG., and , Lord EM. Radiation-induced IFN-γ production within the tumor microenvironment influences antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2008;180:3132–3139. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Auh SL, Wang Y, Burnette B, Wang Y, Meng Y, et al. Therapeutic effects of ablative radiation on local tumor require CD8+ T cells: changing strategies for cancer treatment. Blood. 2009;114:589–595. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Evans JE., and , Rock KL. Molecular identification of a danger signal that alerts the immune system to dying cells. Nature. 2003;425:516–521. doi: 10.1038/nature01991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casares N, Pequignot MO, Tesniere A, Ghiringhelli F, Roux S, Chaput N, et al. Caspase-dependent immunogenicity of doxorubicin-induced tumor cell death. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1691–1701. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeid M, Tesniere A, Ghiringhelli F, Fimia GM, Apetoh L, Perfettini JL, et al. Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nat Med. 2007;13:54–61. doi: 10.1038/nm1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, Obeid M, Ortiz C, Criollo A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med. 2007;13:1050–1059. doi: 10.1038/nm1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Bowerman NA, Salama JK, Schmidt H, Spiotto MT, Schietinger A, et al. Induced sensitization of tumor stroma leads to eradication of established cancer by T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:49–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield P, Merrick A, Harrington K, Vile R, Bateman A, Selby P, et al. Radiation-induced cell death and dendritic cells: potential for cancer immunotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2005;17:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reits EA, Hodge JW, Herberts CA, Groothuis TA, Chakraborty M, Wansley EK, et al. Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1259–1271. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao YP, Wang CC, Butterfield LH, Economou JS, Ribas A, Meng WS, et al. Ionizing radiation affects human MART-1 melanoma antigen processing and presentation by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:2462–2469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty M, Abrams SI, Camphausen K, Liu K, Scott T, Coleman CN, et al. Irradiation of tumor cells up-regulates Fas and enhances CTL lytic activity and CTL adoptive immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2003;170:6338–6347. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett CT, Palena C, Chakraborty M, Chakarborty M, Tsang KY, Schlom J, et al. Sublethal irradiation of human tumor cells modulates phenotype resulting in enhanced killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7985–7994. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcellos-Hoff MH, Park C., and , Wright EG. Radiation and the microenvironment—tumorigenesis and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:867–875. doi: 10.1038/nrc1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura S, Wang B, Kawashima N, Braunstein S, Badura M, Cameron TO, et al. Radiation-induced CXCL16 release by breast cancer cells attracts effector T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:3099–3107. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt AJ, Vijayakumar S, Nemunaitis J, Sandler A, Schwartz H, Hanna N, et al. A Phase I trial of TNFerade biologic in patients with soft tissue sarcoma in the extremities. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5747–5753. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senzer N, Mani S, Rosemurgy A, Nemunaitis J, Cunningham C, Guha C, et al. TNFerade biologic, an adenovector with a radiation-inducible promoter, carrying the human tumor necrosis factor α gene: a phase I study in patients with solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:592–601. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formenti SC., and , Demaria S. Local control by radiotherapy: is that all there is. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:215. doi: 10.1186/bcr2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichselbaum RR., and , Kufe D. Translation of the radio- and chemo-inducible TNFerade vector to the treatment of human cancers. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16:609–619. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2009.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGill RS, Davis TA, Macko J, Mauceri HJ, Weichselbaum RR., and , King CR. Local gene delivery of tumor necrosis factor α can impact primary tumor growth and metastases through a host-mediated response. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2007;24:521–531. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodarev NN, Park J, Kataoka Y, Nodzenski E, Hellman S, Roizman B, et al. Receiver operating characteristic analysis: a general tool for DNA array data filtration and performance estimation. Genomics. 2003;81:202–209. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(02)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitroda SP, Khodarev NN, Beckett MA, Kufe DW., and , Weichselbaum RR. MUC1-induced alterations in a lipid metabolic gene network predict response of human breast cancers to tamoxifen treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5837–5841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812029106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnik A., and , Yoshie O. Chemokines: a new classification system and their role in immunity. Immunity. 2000;12:121–127. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:540–550. doi: 10.1038/nrc1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlin H, Meng Y, Peterson AC, Zha Y, Tretiakova M, Slingluff C, et al. Chemokine expression in melanoma metastases associated with CD8+ T-cell recruitment. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3077–3085. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn GP, Koebel CM., and , Schreiber RD. Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:836–848. doi: 10.1038/nri1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii KJ, Coban C, Kato H, Takahashi K, Torii Y, Takeshita F, et al. A Toll-like receptor-independent antiviral response induced by double-stranded B-form DNA. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:40–48. doi: 10.1038/ni1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Sheehan KC, Shankaran V, Uppaluri R, Bui JD, et al. A critical function for type I interferons in cancer immunoediting. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:722–729. doi: 10.1038/ni1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensbergen PJ, Wijnands PG, Schreurs MW, Scheper RJ, Willemze R., and , Tensen CP. The CXCR3 targeting chemokine CXCL11 has potent antitumor activity in vivo involving attraction of CD8+ T lymphocytes but not inhibition of angiogenesis. J Immunother. 2005;28:343–351. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000165355.26795.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmori Y, Schreiber RD., and , Hamilton TA. Synergy between interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α in transcriptional activation is mediated by cooperation between signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 and nuclear factor κB. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14899–14907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi M., and , Ohmori Y. The transcriptional coactivator CREB-binding protein cooperates with STAT1 and NF-κB for synergistic transcriptional activation of the CXC ligand 9/monokine induced by interferon-γ gene. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:651–660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlom J, Arlen PM., and , Gulley JL. Cancer vaccines: moving beyond current paradigms. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3776–3782. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo-Saito C, Schlom J, Camphausen K, Coleman CN., and , Hodge JW. The requirement of multimodal therapy (vaccine, local tumor radiation, and reduction of suppressor cells) to eliminate established tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4533–4544. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauceri HJ, Beckett MA, Liang H, Sutton HG, Pitroda S, Galka E, et al. Translational strategies exploiting TNF-α that sensitize tumors to radiation therapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16:373–381. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimchi ET, Posner MC, Park JO, Darga TE, Kocherginsky M, Karrison T, et al. Progression of Barrett's metaplasia to adenocarcinoma is associated with the suppression of the transcriptional programs of epidermal differentiation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3146–3154. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusher VG, Tibshirani R., and , Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Histology of primary tumors and DLNs after Ad.Egr-TNF/IR treatment. a. Histology of primary tumors. Histology of primary tumors also showed the massive lymphocyte sized inflammatory cells infiltrating in tumors received Ad.Egr-TNF /IR treatment. WT C57BL/6 (n=12/group) were s.c injected with 5x105 B16.SIY melanoma cells, Ad.Egr-TNF (2x109pu) and control Ad.Egr-Null (2x109pu) virus were intratumorally injected on day 9 and day 10. 20 Gy was delivered on day 10. Tumors were harvested on 7 days post IR. b. Histology of DLNs from same experiments as above only the primary tumors were surgically removed 5 days post IR. Mice were sacrificed and DLNs were collected on day 35. Arrows marked at the margin of metastatic tumor cells.

Small effect of Ad.Egr-TNF/IR on B16.SIY primary tumor regrowth and DLN metastases in CD8 knockout mice. a. CD8 knockout mice with C57BL/6 background (n=12/group) were s.c injected with 5x105 B16.SIY melanoma cells, Ad.Egr-TNF (2x109pu) and control Ad.Null (2x109pu) virus were injected intratumorally on day 9 and day 10. 20 Gy was delivered locally on day 10. b. Small effect of Ad.Egr-TNF /IR on B16.SIY tumor DLN metastases, Lymph node metastases was measured by clonogenic assay.

Gene symbol and abbreviations.

Primer sequences.