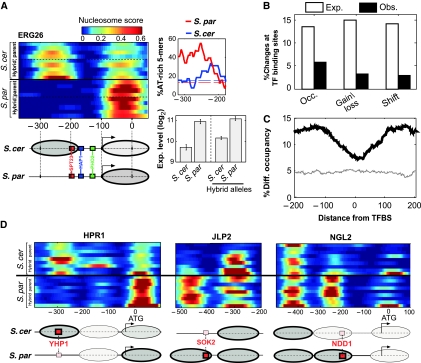

Figure 4.

Divergence of nucleosome positioning is excluded from regulatory elements. (A) Expression divergence of ERG26 is correlated with divergence of nucleosome positioning. ERG26 promoter nucleosome scores are shown for all available strains of the two species and the respective hybrid alleles, indicating the absence of the −1 nucleosome at S. paradoxus. This nucleosome covers a conserved SPT23-binding site and borders a conserved HAP1-binding site. Consistent with this, expression of ERG26 is ∼2-fold higher in S. paradoxus and in the corresponding hybrid allele, than in S. cerevisiae. Also shown is the fraction of AT-rich 5-mers for the two species at the region of the −1 nucleosome. (B) The percentage of promoter changes for each class that overlaps conserved TFBSs (MacIsaac et al, 2006), compared with the expected percentage calculated by shuffling (P<0.05 for each of the three classes). (C) Percentage of positions with significant differences (P<0.05, t-test), as a function of the distance from conserved TFBS (MacIsaac et al, 2006), for comparison of all strains from the two different species (black) or for biological repeats of S. cerevisiae (gray). (D) Examples where nucleosome changes appear to be compensated by divergence of binding sites. Red boxes correspond to high-scoring binding sites, and smaller pink boxes correspond to weaker binding site (lower by at least two in LOD score based on MacIsaac et al). Ovals correspond to nucleosomes and their color represents occupancy (brighter ovals represent nucleosomes with low occupancy). In two of these cases (JLP2 and NGL2), expression is higher for S. paradoxus (not shown), suggesting that divergence of the motif had a more significant influence than divergence of the nucleosome. For the third case (HPR1), we do not have expression data.