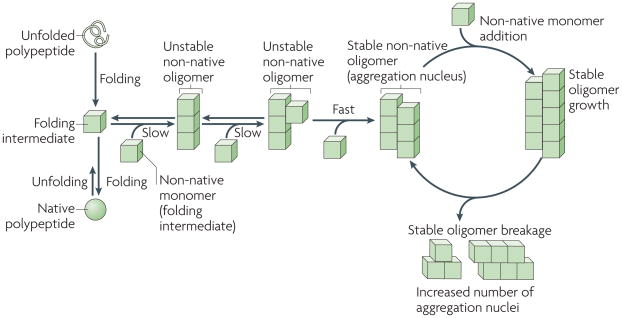

Figure 1. Basic mechanisms of protein aggregation.

The folding of newly synthesized polypeptide chains into their native conformations and the unfolding of proteins from their native states proceeds through distinct intermediates. some of these intermediates are able to self-associate to form non-native oligomeric species of different sizes and structures, in which a given molecule interacts through two interfaces with two neighbouring molecules (an intermediate in which longitudinal interactions are established is shown). As the polypeptides involved in prion, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s diseases populate a wide variety of folding intermediates, they have a higher propensity to form such oligomeric species. The stability of these oligomers increases on establishment of supplementary intermolecular interactions with non-native polypeptides through additional interfaces, as a given molecule in the oligomer becomes multivalent. The rate-limiting step in non-native polypeptide aggregation is therefore the formation of stable oligomers. Such oligomers behave as nuclei and grow from their ends by recruiting non-native monomers. As the binding of a molecule to the oligomer generates an incorporation site for another subunit, the growth of the stable nuclei is unlimited. Brownian52 movement and severing and/or disaggregating factors generate increased numbers of ends and increase the likelihood of new subunits being incorporated.