Abstract

Background

There is increasing interest in the evolution of protein-protein interactions because this should ultimately be informative of the patterns of evolution of new protein functions within the cell. One model proposes that the evolution of new protein-protein interactions and protein complexes proceeds through the duplication of self-interacting genes. This model is supported by data from yeast. We examined the relationship between gene duplication and self-interaction in the human genome.

Results

We investigated the patterns of self-interaction and duplication among 34808 interactions encoded by 8881 human genes, and show that self-interacting proteins are encoded by genes with higher duplicability than genes whose proteins lack this type of interaction. We show that this result is robust against the system used to define duplicate genes. Finally we compared the presence of self-interactions amongst proteins whose genes have duplicated either through whole-genome duplication (WGD) or small-scale duplication (SSD), and show that the former tend to have more interactions in general. After controlling for age differences between the two sets of duplicates this result can be explained by the time since the gene duplication.

Conclusions

Genes encoding self-interacting proteins tend to have higher duplicability than proteins lacking self-interactions. Moreover these duplicate genes have more often arisen through whole-genome rather than small-scale duplication. Finally, self-interacting WGD genes tend to have more interaction partners in general in the PIN, which can be explained by their overall greater age. This work adds to our growing knowledge of the importance of contextual factors in gene duplicability.

Background

Proteins have an impact on the cell through interactions with other components of the system. One type of interaction, Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI), has received much attention in the literature because of the possibilities of genome-wide surveys, such as yeast two-hybrid screens, and the tractability of analysis. In particular, the evolution of PPIs and how this relates to other aspects of molecular evolution is very interesting.

One special category of PPI is the interaction between identical copies of a protein produced from the same gene (self-interaction) forming homomers. These comprise a significant fraction of the protein interaction network (PIN) due to genetic factors: the interacting partners are translated from the same mRNA and so are ipso facto co-regulated and co-localized in the cell; as well as biochemical factors: identical proteins are expected to have high affinity for each other [1].

Gene duplication can act to shape the protein interaction network because although an identical protein copy produced from a duplicate gene will perform the same interactions as the original, over time the protein sequences and the interactions they participate in will diverge [2]. In particular, the ancestral number of interactions may influence the dynamics of gain and loss of protein interactions after gene duplication [3]. It has previously been shown that gene duplicability can be influenced by factors such as dosage-balance constraints [4], connectivity in interaction networks [5] and function [6]. The duplicability of genes also differs between small-scale (SSD) and whole genome duplication (WGD) [7,8].

Several recent studies have examined the duplication of genes whose protein product can interact with a copy of itself (for simplicity we call these "self-interacting genes") [2,9-11]. Pereira-Leal and colleagues investigated the evolutionary origins of protein complexes and concluded that they evolve through duplication of homodimers, that is through duplication of genes coding for self-interacting proteins [10]. They showed that protein interactions amongst paralogous proteins occur more frequently than can be expected purely by chance in yeast, worm and fly. They also show that protein-protein interactions between homodimers and paralogous dimers (interactions between paralogous proteins) in these species are not independent, and conclude that the latter dimer type evolved from the former, something that had been suggested previously [12]. They argue that gene duplication and divergence are important forces driving the expansion of the eukaryotic proteome, and that multiple copies of identical subunits are an economical way of forming larger functional structures. Another study, which modelled the yeast protein interaction network before and after WGD found evidence for greater retention of self-interacting genes in duplicate [11], and so is consistent with this hypothesis.

With a few exceptions (e.g., ref [9]) most previous studies have used the yeast strain S. cerevisiae as a model organism. This is convenient, as thorough, full-scale proteomic interaction studies have been conducted in yeast using affinity purification and mass spectronomy (AP-MS) to gain knowledge of protein complexes [13]. Moreover there is complete genome sequence of several other yeast species for evolutionary comparisons, and extensive protein interaction data between protein pairs are available in the Database of Interacting Proteins (DIP) [14].

In this study we investigate the duplicability of self-interacting genes in human. We also examine the impact of the extent of the duplication event by comparing SSD duplicate genes with WGD duplicate genes. Our results support the model of preferential retention of duplicated self-interacting genes. This result is robust against the method used to define duplicability. We also show a greater enrichment of self-interacting genes among WGD duplicates than SSD duplicates and relate this to an overall higher connectivity of WGD genes in the protein-interaction network.

Results and Discussion

Higher duplicability of self-interacting genes

We examined 34808 interactions between products of 8881 genes, 1879 of which are self-interacting (Figure 1). The protein interactions follow a power-law distribution, a typical feature of biological networks [15,16]. Singletons were defined as human genes with no BLASTP hit in the human genome (other than self-hits) at an E-value threshold of 0.1. Duplicate genes had a non-self BLASTP hit in the human genome with an E-value less than or equal to 1 × 10-20. Genes with hits with intermediate E-values were excluded as ambiguous. Consistent with previous studies [9,10] we found that duplicated genes are enriched for self-interactions (χ2 = 45.02, p = 1.96 × 10-11) and this result does not depend on the E-value used to define duplicate genes (see Additional file 1).

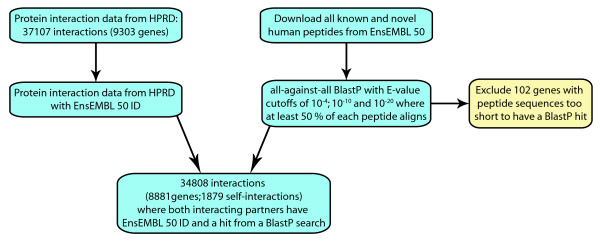

Figure 1.

Data collection. Flow chart illustrating how the human interaction data were collected from HPRD release 7, and subsequently matched with blastable Ensembl Core release 50 identifiers in order to extract the final 8881 genes involved in 34808 protein-protein interactions.

Since homomers can give rise to heteromers through the duplication of self-interacting proteins one possible outcome of the duplication of self-interacting genes is that the self-interaction is lost as the interaction between paralogs is favoured, perhaps because it permits greater evolutionary novelty. If this is the case it may reduce the apparent duplicability of self-interacting genes when duplications and interactions are measured in the same organism [17,18]. Similarly, interactions may be gained after gene duplication. In order to exclude the possibility that the gene duplication interferes with the interaction status of the protein products we measured duplicability in a sister lineage.

We searched for mouse orthologs of the human genes using Ensembl Compara and defined a singleton gene as a human gene that had a one to one ortholog in mouse, while a duplicate gene was a human gene with at least two co-orthologous genes in mouse (i.e., mouse lineage-specific duplication; Figure 2). Thus only human genes that have not experienced a recent human lineage-specific duplication (within the last 90-100 myr) are considered, and duplicability is assessed by the status in the mouse genome (Table 1). For our analysis we could only use genes with available interaction information, however the proportion of duplicated genes (mouse-specific duplication) in this reduced dataset (2.28%) is comparable to the proportion for the whole dataset (2.83%) so we infer that no bias is introduced. We find that orthologs of human self-interacting genes have greater duplicability in the mouse lineage (χ2 = 3.96, df = 1, p = 0.047). The fact that the duplicated genes in this dataset are recently duplicated (since the mouse-human divergence) indicates that this is an ongoing phenomenon.

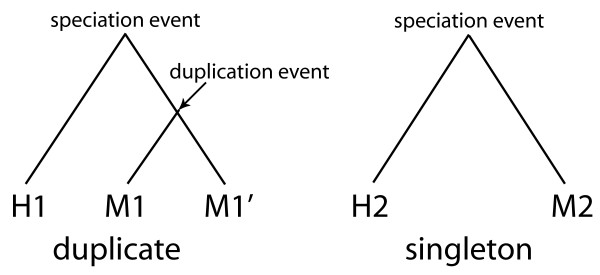

Figure 2.

Definition of mouse-specific duplicate genes in human. Human genes (H) were classified as singletons if they had a one to one orthologous relationship with mouse (M), and as mouse-specific duplicate genes if the relationship with mouse was one to many i.e. if one human gene had at least two orthologous genes in the mouse lineage.

Table 1.

Proportion of self-interacting singletons and duplicates.

| Classification system | self-interacting | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human BLASTP | Singletons | 433 (16%) | 2595 |

| Duplicates | 1285 (23%) | 5531 | |

| Mouse duplicability | 1:1 orthologs | 1682 (21%) | 7968 |

| 1:many orthologs | 51 (27%) | 186 |

WGD genes are enriched for self-interactions by comparison with SSD genes

Previous studies have shown different properties for genes duplicated by SSD or WGD [19,20]. In particular, dosage-balance constraints result in different duplication outcomes under WGD (biased retention) and SSD (lower duplicability). To investigate whether the mechanism of duplication influences the retention of self-interacting genes we compared genes duplicated by the two mechanisms. It has been observed in yeast that genes that form heteromers (complexes of proteins encoded by different genes) have fewer paralogs than other genes, since the integrity of the complex depends on duplication of all, or none, of the genes in the complex [4]. In the human data, 25% of genes duplicated by WGD are self-interacting compared to only 21% of SSD-duplicated genes, a significant difference (χ2 = 10.67, df = 1, p = 0.0011; Table 2). Because self-interaction does not depend on other genes this observation is not immediately reconcilable with between-gene dosage-balance explanations for WGD gene retention. However, it was previously noted that self-interacting proteins tend to have more interacting partners (higher connectivity) than non-self-interacting genes [9] and we confirm this for our dataset. Thus the higher fraction of self-interacting WGD genes may be due to an indirect effect of a greater number of interactions (and thus greater tendency for dosage-balance constraints on these genes).

Table 2.

Proportion of self-interacting duplicate genes generated by different mechanisms.

| Duplication Mechanism | self-interacting | Total |

|---|---|---|

| WGD | 717 (25%) | 2877 |

| SSD | 630 (21%) | 2961 |

WGD genes have more interaction partners on average than SSD genes

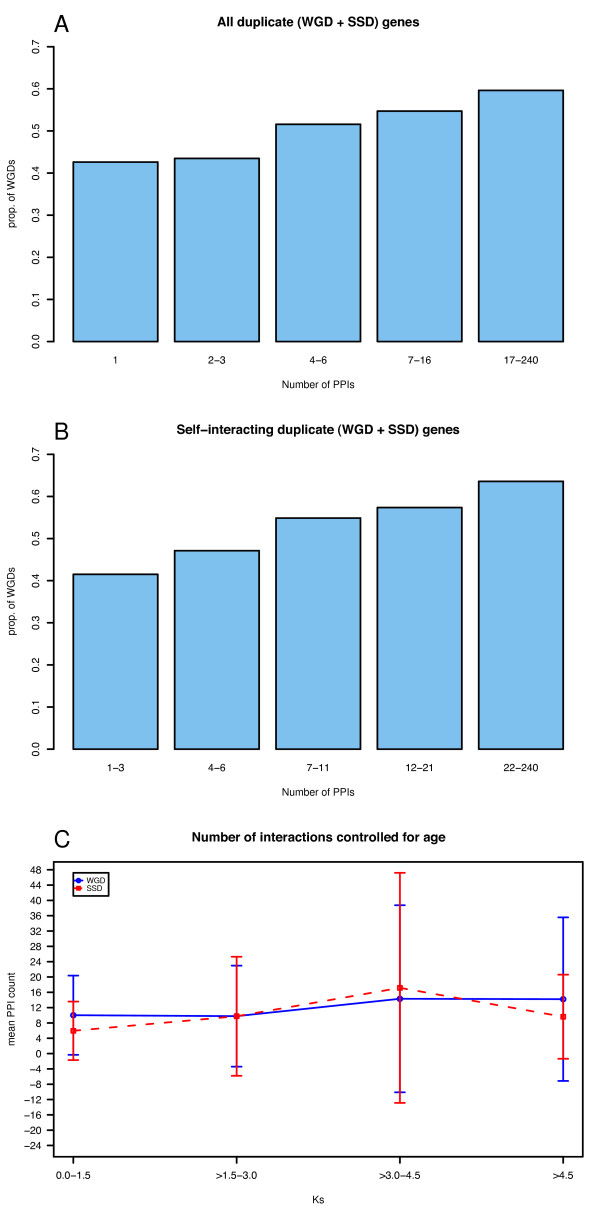

To further investigate the relationship of protein interaction network connectivity and duplicability we examined the number of interacting partners of duplicated genes. We find that the genes with a higher number of interactions contain a greater proportion of genes duplicated by WGD, and that this is true irrespective of self-interaction (p < 2 × 10-16 and p = 1.03 × 10-7 respectively, logistic regression; Figure 3a-b and Figure S2, Additional file 1). However, it was previously noted in yeast that older genes tend to have more interaction partners [21,22] and when we control for age of duplication, we find no difference in connectivity between all WGD and SSD duplicates (Figure 3c) or between self-interacting WGD and SSD duplicates (results not shown).

Figure 3.

Relationship of duplication type and number of interactions. The proportion of WGD genes among all duplicate (WGD and SSD) genes increases with increased number of protein-protein interactions irrespective of self-interactions. a) Proportion of WGD genes among all duplicate genes with respect to the number of interactions. (Bins created to contain similar amounts of genes.) b) Proportion of self-interacting WGD genes among all self-interacting duplicate genes with respect to the number of interactions. (Bins created to contain similar amounts of genes.) c) Relationship of synonymous divergence rate, and the number of PPI partners of each gene in the duplicate pair. The x-axis displays the synonymous substitution rate (KS) between a duplicate pair, while the y-axis is the mean value of the total number of PPIs of all genes in each KS bin (category).

We therefore considered whether the enrichment for self-interactions is truly a generality of duplicated genes, or is only a feature of WGD-duplicated genes which are older on average than SSD-duplicated genes and tend to have a higher number of interaction partners. Indeed, the enrichment for self-interaction among WGD genes compared to singletons is highly significant (χ2 = 55.88, df = 1, p = 7.69 × 10-14), but so too is the enrichment among SSD-duplicated genes (χ2 = 19.92, df = 1, p = 8.08 × 10-6). Thus we conclude that self-interaction is a general feature of duplicated genes that is influenced by the mode of duplication and the total number of interactions, but not determined by those features.

Self-interacting genes are enriched for developmental and essential biological processes, and WGD self-interacting genes are involved in metabolism

In order to understand the biological impact of duplication of self-interacting genes, we examined their functions using Gene Ontology (GO) terms. We found that self-interacting genes are enriched for biological processes such as early development (GO:0030154 and GO:0007275), cell death, cell communication and response to stimulus, and molecular functions such as protein binding, kinase and transferase activity as well as receptor activity (Table 3). We then compared duplicated against singleton genes, and found that while the first set of genes are over-represented for cell communication and cell differentiation, and molecular functions including binding, receptor activity and channel activity; they are under-represented for metabolic and catabolic processes, nucleic acid binding and ligase activity (Table 4). Finally we compared self-interacting WGD and SSD genes against each other, and found that while the WGD genes are under-represented for response to stimulus, oxidoreductase, anitoxidant and hydrolase activity the same set of genes are over-represented for regulation of biological processes, metabolic processes, kinase, transferase and transcription regulation activity (Table 5). Thus, genes involved in metabolic processes are under-represented among duplicate genes in general, but enriched in WGD-duplicated genes compared to SSD-duplicated genes. This is consistent with a recent report by Gout and colleagues which showed that after WGD, metabolic genes are retained more often than non-metabolic genes due to selection for gene expression on the entire metabolic pathway [7].

Table 3.

Over-represented GO terms when self- and nonself-interacting genes are compared against each other.

| Biological Processes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO IDs | Term | Obs. | Mean | S. D. | Z score | p-valuea |

| GO:0008219 | cell death | 197 | 116.651 | 8.8 | 9.1 | 2.12E-16 |

| GO:0007154 | cell communication | 588 | 480.984 | 15.4 | 6.9 | 2.78E-11 |

| GO:0050789 | regulation of biological process | 855 | 748.686 | 15.3 | 7.0 | 4.33E-11 |

| GO:0051704 | multi-organism process | 116 | 66.152 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 1.41E-10 |

| GO:0006928 | cell motion | 113 | 71.586 | 7.0 | 5.9 | 8.45E-07 |

| GO:0050896 | response to stimulus | 321 | 252.834 | 12.2 | 5.6 | 1.42E-06 |

| GO:0007610 | behavior | 86 | 52.189 | 6.0 | 5.6 | 3.96E-06 |

| GO:0009987 | cellular process | 833 | 764.383 | 15.3 | 4.5 | 8.67E-05 |

| GO:0030154 | cell differentiation | 222 | 173.684 | 10.3 | 4.7 | 1.66E-04 |

| GO:0043170 | macromolecule metabolic process | 697 | 628.169 | 15.9 | 4.3 | 1.79E-04 |

| GO:0007275 | multicellular organismal development | 374 | 321.383 | 12.9 | 4.1 | 2.29E-03 |

| GO:0032501 | multicellular organismal process | 222 | 188.816 | 10.8 | 3.1 | 4.20E-02 |

| Molecular Functions | ||||||

| GO IDs | Term | Obs. | Mean | S. D. | Z score | p-valuea |

| GO:0005515 | protein binding | 1026 | 874.792 | 14.8 | 10.2 | 1.25E-23 |

| GO:0016301 | kinase activity | 208 | 118.109 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 2.34E-19 |

| GO:0016740 | transferase activity | 213 | 145.362 | 10.3 | 6.6 | 1.52E-09 |

| GO:0004871 | signal transducer activity | 113 | 75.003 | 7.3 | 5.2 | 2.24E-05 |

| GO:0004872 | receptor activity | 208 | 169.553 | 11.0 | 3.5 | 1.22E-02 |

a The estimated P values were adjusted by Bonferroni correction.

Table 4.

Over- and under-represented (italics) GO terms when duplicated genes are compared against singleton genes.

| Biological processes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO IDs | Term | Obs. | Mean | S. D. | Z score | p-valuea |

| GO:0007154 | cell communication | 2009 | 1819.3 | 17.5 | 10.8 | 5.86E-27 |

| GO:0006139 | nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolic process | 1446 | 1630.6 | 16.6 | -11.1 | 4.08E-25 |

| GO:0009058 | biosynthetic process | 1522 | 1650.6 | 17.0 | -7.6 | 2.21E-12 |

| GO:0050789 | regulation of biological process | 3130 | 3001.9 | 18.3 | 7.0 | 5.91E-11 |

| GO:0007275 | multicellular organismal development | 1346 | 1241.1 | 15.8 | 6.7 | 1.76E-10 |

| GO:0032501 | multicellular organismal process | 787 | 712.5 | 12.4 | 6.0 | 2.34E-08 |

| GO:0022904 | respiratory electron transport chain | 3 | 14.9 | 1.9 | -6.2 | 1.45E-06 |

| GO:0043170 | macromolecule metabolic process | 2628 | 2726.8 | 18.2 | -5.4 | 1.72E-06 |

| GO:0030154 | cell differentiation | 726 | 673.2 | 12.1 | 4.4 | 3.02E-04 |

| GO:0007610 | behavior | 218 | 189.6 | 7.1 | 4.0 | 3.39E-04 |

| GO:0006928 | cell motion | 300 | 267.4 | 8.3 | 3.9 | 6.67E-04 |

| GO:0009056 | catabolic process | 452 | 487.6 | 11.0 | -3.2 | 1.70E-02 |

| GO:0005634 | nucleus | 1 | 5.1 | 1.2 | -3.4 | 4.85E-02 |

| GO:0016787 | hydrolase activity | 1 | 5.1 | 1.2 | -3.4 | 4.85E-02 |

| Molecular Function | ||||||

| GO IDs | Term | Obs. | Mean | S. D. | Z score | p-valuea |

| GO:0005488 | binding | 2905 | 2686.899 | 18.3 | 11.9 | 3.85E-29 |

| GO:0004872 | receptor activity | 714 | 608.911 | 12.3 | 8.6 | 2.06E-19 |

| GO:0016301 | kinase activity | 496 | 420.462 | 10.0 | 7.5 | 4.99E-14 |

| GO:0015267 | channel activity | 203 | 159.644 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 1.28E-12 |

| GO:0015075 | ion transmembrane transporter activity | 300 | 247.312 | 8.1 | 6.5 | 2.48E-11 |

| GO:0004871 | signal transducer activity | 315 | 265.132 | 8.2 | 6.1 | 2.76E-09 |

| GO:0003676 | nucleic acid binding | 1211 | 1290.829 | 16.5 | -4.8 | 3.31E-05 |

| GO:0016787 | hydrolase activity | 870 | 813.748 | 13.8 | 4.1 | 7.61E-04 |

| GO:0045182 | translation regulator activity | 36 | 51.717 | 3.6 | -4.3 | 2.28E-03 |

| GO:0003774 | motor activity | 68 | 55.557 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 1.09E-02 |

| GO:0016874 | ligase activity | 138 | 161.46 | 6.4 | -3.7 | 1.21E-02 |

a The estimated P values were adjusted by Bonferroni correction.

Table 5.

Over- and under-representation (italics) of GO terms in self-interacting WGD with respect to SSD genes.

| Biological processes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO IDs | Term | Obs. | Mean | S. D. | Z score | p-valuea |

| GO:0050896 | response to stimulus | 138 | 171.285 | 7.5 | -4.4 | 0.000246911 |

| GO:0050789 | regulation of biological process | 484 | 456.64 | 8.2 | 3.3 | 0.017011463 |

| GO:0043170 | macromolecule metabolic process | 399 | 372.058 | 9.1 | 2.9 | 0.039105725 |

| Molecular Function | ||||||

| GO IDs | Term | Obs. | Mean | S. D. | Z score | p-valuea |

| GO:0016301 | kinase activity | 143 | 111.112 | 6.7 | 4.8 | 3.34E-05 |

| GO:0016740 | transferase activity | 141 | 113.834 | 6.8 | 4.0 | 1.17E-03 |

| GO:0030528 | transcription regulator activity | 134 | 107.982 | 6.7 | 3.9 | 1.67E-03 |

| GO:0016491 | oxidoreductase activity | 14 | 25.711 | 3.3 | -3.6 | 1.93E-02 |

| GO:0016209 | antioxidant activity | 0 | 4.858 | 1.5 | -3.2 | 4.16E-02 |

| GO:0016787 | hydrolase activity | 81 | 101.071 | 6.3 | -3.2 | 4.37E-02 |

a The estimated P values were adjusted by Bonferroni correction.

Conclusions

We observed greater duplicability of human self-interacting genes and that WGD duplicate genes tend to be self-interacting more often than SSD duplicate genes. This latter observation probably relates to the higher overall connectivity of WGD genes in protein interaction networks. Highly connected genes are more likely to be subject to dosage balance constraints and so to be resistant to SSD, but preferentially retained after WGD [4,8]. This result is also consistent with studies in yeast which showed preferential retention of interacting genes after WGD as a possible explanation of the protein interaction network dynamics [11]. Moreover, consistent with previous observations in yeast [21,22], we found that protein connectivity is correlated with the time since gene duplication. Our results also support the hypothesis that duplication of self-interacting proteins should be selectively advantageous because it facilitates the evolution of complex protein structures [2].

Methods

Filtering of human protein-protein interaction data

We obtained 37,107 PPIs involving 9303 genes from the Human Protein Reference Database (HPRD) release 7 [23,24]. We excluded interactions where either of the interacting partners could not be linked to an Ensembl release 50 identifier [25] as well as 13 genes that were too short or simple for the BLASTP sequence similarity search. Thus, the final dataset consisted of 34808 interactions, encoded by 8881 (1879 self-interacting) genes.

Definition of singleton and duplicate genes

An all against all BLASTP search [26] of all known and novel human peptides present in Ensembl Core release 50 [25] was performed to define singleton and duplicate genes in human. Singleton genes were defined as genes whose protein products lack any non-self hit with an E-value less than 0.1. A gene was considered to be a duplicated gene if its top, non-self hit had an E-value less than or equal to 1 × 10-20, and at least 50% of the two peptides aligned. Genes with BLAST hits at intermediate E-values (less than 0.1 but larger than 1 × 10-20) were considered ambiguous genes, which could neither be classified as singleton or duplicate genes. The analyses were repeated with E-value thresholds of 1 × 10-4, 1 × 10-10 and the results were consistent. Also, 102 genes lacked hits after the BLASTP search was performed (i.e., not even a self-hit). The reason for missing hits could all be assigned to low complexity (simple sequence) masking or too-short peptide sequences and these were excluded from further analysis.

Definition of singleton and duplicate genes for the comparative study

Genes that have not recently duplicated in the human lineage (since the human-mouse split) were examined for mouse lineage-specific duplication using data from the Ensembl Compara release 50 [25] from human (Homo sapiens) and mouse (Mus musculus). A singleton gene was classified as a gene that had a one to one orthologous relationship between the two species, while a duplicate gene was a single human gene with at least two orthologous genes in mouse (1:many relationship; Figure 2).

Comparison of WGD duplicate genes vs SSD duplicate genes

2877 WGD-duplicated genes (also known as ohnologs) with available PPI data were obtained from Nakatani et al. [27]. 307 genes that were not classified by us as duplicated based on our criteria of BLASTP sequence similarity and alignment length (above) were classified as WGD-duplicate genes based on Nakatani's analysis which includes comparative gene synteny. Thus the final dataset consisted of 2877 WGD genes and 2961 SSD-duplicated genes (Table 2).

We applied simple logistic regression [28,29] to measure the proportion of genes encoding self-interacting proteins over all genes with a particular number of interacting partners (degree) k, and in accordance with Ispolatov and colleagues [9] we found that self-interacting genes tend to have more interacting partners in general (not shown). We then measured the proportion of WGD genes over all duplicate genes (WGD and SSD genes) with degree k.

Gene Ontology analyses

Gene Ontology (GO) terms related to biological process and molecular function were examined for sets of self- and nonself-interacting genes, self-interacting WGD and SSD genes, and duplicated and singleton genes using GO slim [30]converted by human GO identifiers [31] (both available from http://www.geneontology.org). Expected values were estimated by simulation, and p-values were calculated as the difference between the expected and observed under hypergeometric distribution. Finally the estimated p-values were adjusted by Bonferroni correction.

Abbreviations

PPI: Protein-protein interaction; PIN: Protein interaction network; WGD: Whole genome duplication; SSD: Small scale duplication; GO: Gene ontology.

Authors' contributions

ÅPB and AMcL devised the project. ÅPB and TM carried out experiments. ÅPB, TM and AMcL analysed the data. ÅPB and AMcL wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Additional methods and results.

Contributor Information

Åsa Pérez-Bercoff, Email: perezbea@tcd.ie.

Takashi Makino, Email: tamakino@m.tains.tohoku.ac.jp.

Aoife McLysaght, Email: aoife.mclysaght@tcd.ie.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Karsten Hokamp and Gavin Conant for discussion. This work is supported by Science Foundation Ireland.

References

- Lukatsky DB, Shakhnovich BE, Mintseris J, Shakhnovich EI. Structural similarity enhances interaction propensity of proteins. J Mol Biol. 2007;365(5):1596–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy ED, Pereira-Leal JB. Evolution and dynamics of protein interactions and networks. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18(3):349–357. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Luo ZW, Kishino H, Kearsey MJ. Divergence pattern of duplicate genes in protein-protein interactions follows the power law. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2005;22(3):501–505. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp B, Pal C, Hurst LD. Dosage sensitivity and the evolution of gene families in yeast. Nature. 2003;424(6945):194–197. doi: 10.1038/nature01771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, Li WH. Gene essentiality, gene duplicability and protein connectivity in human and mouse. Trends Genet. 2007;23(8):375–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaldi D, Giorgi FM, Capuani F, Ciliberto A, Ciccarelli FD. Low duplicability and network fragility of cancer genes. Trends Genet. 2008;24(9):427–430. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gout JF, Duret L, Kahn D. Differential retention of metabolic genes following whole-genome duplication. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26(5):1067–1072. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino T, Hokamp K, McLysaght A. The complex relationship of gene duplication and essentiality. Trends Genet. 2009;25(4):152–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ispolatov I, Yuryev A, Mazo I, Maslov S. Binding properties and evolution of homodimers in protein-protein interaction networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(11):3629–3635. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Leal JB, Levy ED, Kamp C, Teichmann SA. Evolution of protein complexes by duplication of homomeric interactions. Genome Biol. 2007;8(4):R51. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presser A, Elowitz MB, Kellis M, Kishony R. The evolutionary dynamics of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein interaction network after duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(3):950–954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707293105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A. The yeast protein interaction network evolves rapidly and contains few redundant duplicate genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18(7):1283–1292. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin AC, Aloy P, Grandi P, Krause R, Boesche M, Marzioch M, Rau C, Jensen LJ, Bastuck S, Dumpelfeld B. Proteome survey reveals modularity of the yeast cell machinery. Nature. 2006;440(7084):631–636. doi: 10.1038/nature04532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Database of Interacting Proteins. http://dip.doe-mbi.ucla.edu/

- Albert R. Scale-free networks in cell biology. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 21):4947–4957. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabasi AL, Albert R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science. 1999;286(5439):509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JC, Petrov DA. Preferential duplication of conserved proteins in eukaryotic genomes. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(3):E55. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Zhang J. Higher duplicability of less important genes in yeast genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(1):144–151. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y, Dunham MJ, Troyanskaya OG. Functional analysis of gene duplications in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2007;175(2):933–943. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.064329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakes L, Pinney JW, Lovell SC, Oliver SG, Robertson DL. All duplicates are not equal: the difference between small-scale and genome duplication. Genome Biol. 2007;8(10):R209. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunin V, Pereira-Leal JB, Ouzounis CA. Functional evolution of the yeast protein interaction network. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21(7):1171–1176. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prachumwat A, Li WH. Protein function, connectivity, and duplicability in yeast. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(1):30–39. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshava Prasad TS, Goel R, Kandasamy K, Keerthikumar S, Kumar S, Mathivanan S, Telikicherla D, Raju R, Shafreen B, Venugopal A. Human Protein Reference Database--2009 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009. pp. D767–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Peri S, Navarro JD, Amanchy R, Kristiansen TZ, Jonnalagadda CK, Surendranath V, Niranjan V, Muthusamy B, Gandhi TK, Gronborg M. Development of human protein reference database as an initial platform for approaching systems biology in humans. Genome Res. 2003;13(10):2363–2371. doi: 10.1101/gr.1680803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicek P, Aken BL, Beal K, Ballester B, Caccamo M, Chen Y, Clarke L, Coates G, Cunningham F, Cutts T. Ensembl 2008. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008. pp. D707–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatani Y, Takeda H, Kohara Y, Morishita S. Reconstruction of the vertebrate ancestral genome reveals dynamic genome reorganization in early vertebrates. Genome Res. 2007;17(9):1254–1265. doi: 10.1101/gr.6316407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley MJ. Statistics An Introduction using R. Wiley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Handbook of Biological Statistics. http://udel.edu/~mcdonald/statintro.html

- GO slim. ftp://ftp.geneontology.org/pub/go/GO_slims/goslim_goa.obo

- GO identifiers. ftp://ftp.geneontology.org/pub/go/gene-associations/gene_association.goa_human.gz

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional methods and results.