Abstract

Background

Reproductive control including pregnancy coercion (coercion by male partners to become pregnant) and birth control sabotage (partner interference with contraception) may be associated with partner violence and risk for unintended pregnancy among young adult females utilizing family planning clinic services.

Study Design

A cross-sectional survey was administered to females ages 16–29 years seeking care in five family planning clinics in Northern California (N=1278).

Results

Fifty-three percent of respondents reported physical or sexual partner violence, 19% reported experiencing pregnancy coercion, and 15% reported birth control sabotage. One third of respondents reporting partner violence (35%) also reported reproductive control. Both pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage were associated with unintended pregnancy (AOR 1.83, 95% CI 1.36, 2.46, and AOR 1.58, 95% CI 1.14, 2.20, respectively). In analyses stratified by partner violence exposure, associations of reproductive control with unintended pregnancy persisted only among women with a history of partner violence.

Conclusions

Pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage are common among young women utilizing family planning clinics, and in the context of partner violence, are associated with increased risk for unintended pregnancy.

Keywords: Pregnancy, unwanted, Domestic Violence, Contraception, barrier, Family Planning Services

1. Introduction

Nearly one in four women in the United States report experiencing violence by a current or former spouse or boyfriend at some point in her life [1], with adolescents and young adults at highest risk for intimate partner violence [2–5]. Studies have highlighted the association between partner violence and unintended pregnancy [6–14]. Recent evidence suggests these associations co-occur with reproductive control, i.e., male partners’ attempts to control a woman’s reproductive choices. Abused women face compromised decision-making regarding, or limited ability to enact, contraceptive use and family planning, including fear of condom negotiation [9, 15–20]. Women’s lack of control over her reproductive health is increasingly recognized as a critical mechanism underlying abused women’s elevated risk for unintended pregnancy [21, 22].

One specific element of abusive men’s control that may, in part, explain the association of partner violence with unintended pregnancy is overt pregnancy coercion and direct interference with contraception. Some males use verbal demands, threats, and physical violence to pressure their female partners to become pregnant [12, 23, 24]. Reproductive control may also take the form of direct acts that ensure a woman cannot use contraception -- birth control sabotage – including flushing birth control pills down the toilet, intentional breaking of condoms, and removing contraceptive rings or patches [23, 24]. The extent to which reproductive control and the elements of pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage are associated with physical and/or sexual violence in intimate relationships is not known.

Family planning clinics provide an important venue for examination of these phenomena, as family planning clients are known to experience a higher prevalence of partner violence than the general population [25, 26], and are frequently seeking care for pregnancy-related issues, providing opportunities for intervention. This study examines: 1) the prevalence of pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage, 2) associations of such reproductive control with partner violence, 3) whether such reproductive control is associated with unintended pregnancy, and 4) whether such associations are affected by the co-occurrence of partner violence, among clients seeking reproductive health services at family planning clinics.

2. Materials and methods

The current study was conducted via a cross-sectional survey of English- and Spanish-speaking females ages 16–29 years seeking care in five family planning clinics in California that served as baseline data for an intervention study. Clients were recruited from August 2008 to March 2009. Upon arrival to a clinic, females seeking any health services were screened for age eligibility by trained research staff. Eligible women interested in participating were escorted to a private area in the clinic for consent and survey administration. As participants were receiving confidential services, parental consent for participation was waived for minors.

Data were collected via Audio Computer Assisted Survey Instrument, a self-administered computer program that allows participants to complete surveys on a laptop computer with questions read aloud through headphones. Each participant received a violence-related resource card and a $15 gift card to thank them for their time. All materials were provided in English or Spanish based on patient preference. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by Human Subjects Research Committees at the University of California Davis, Harvard School of Public Health, and Planned Parenthood Federation of America; the data were protected with a federal Certificate of Confidentiality.

Eligible female clients (n=1479) were recruited, and 1319 agreed to complete the survey, resulting in a participation rate of 89%. The final sample size was determined by outcomes of interest for the intervention study. The primary reasons for non-participation were lack of time and plans to move away from the local area in the near future (these individuals were disqualified based on the need for a follow-up survey three months later for the parent study). For the purpose of analysis, women reporting never having sex (n=20) and those that were missing data for key indicators (birth control sabotage: n=17; pregnancy coercion: n=19) were removed from the sample resulting in an effective sample size of 1278.

2.1.Measures

Single items assessed demographic characteristics including age, ethnicity, education level, and immigrant status. Participants were asked ““How many times have you been pregnant when you didn't want to be?”; those reporting once or more were classified as having experienced unintended pregnancy.

Intimate relationships were defined as “your sexual or dating relationships.” Lifetime histories of physical and sexual violence were assessed using items modified from the Conflict Tactics Scales-2 (CTS-2) [27] and Sexual Experiences Survey [28].

Pregnancy coercion was assessed using an investigator-developed assessment consisting of the following six items: “Has someone you were dating or going out with ever:” 1) told you not to use any birth control (like the pill, shot, ring, etc.)?; 2) said he would leave you if you didn’t get pregnant?; 3) told you he would have a baby with someone else if you didn’t get pregnant?; 4) hurt you physically because you did not agree to get pregnant?; and 5) tried to force or pressure you to become pregnant? The final item for this assessment was “Have you ever hidden birth control from a sexual partner because you were afraid he’d get upset with you for using it?” Pregnancy coercion was defined as a positive answer to any of these items.

Birth control sabotage was assessed via five items specific to acts of contraception interference developed by the investigators based on prior qualitative work [23]. Participants were asked, “Has someone you were dating or going out with ever:” 1) taken off the condom while you were having sex so that you would get pregnant?; 2) put holes in the condom so you would get pregnant?; 3) broken a condom on purpose while you were having sex so you would get pregnant?; 4) taken your birth control (like pills) away from you or kept you from going to the clinic to get birth control so that you would get pregnant?; 5) made you have sex without a condom so you would get pregnant? Birth control sabotage was defined as a positive answer to any of these items.

The pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage binary variables were both considered singly and combined disjunctively to create a third binary variable representing a broader array of experiences of reproductive control.

Lifetime prevalence estimates of intimate partner violence, birth control sabotage, pregnancy coercion, and composite reproductive control were calculated, and bivariate associations among these indicators were reported as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Differences in demographic characteristics with partner violence, pregnancy coercion, birth control sabotage, and unintended pregnancy were assessed via chi-square analyses; significance for all analyses was set at p<.05. Differences in unintended pregnancy based on exposure to partner violence, pregnancy coercion, birth control sabotage and reproductive control were assessed via logistic regression models. Models for the effects of pregnancy coercion, birth control sabotage and reproductive control were subsequently adjusted for recruitment site, age, ethnicity, and immigrant status as potential confounders, and stratified by presence of partner violence to evaluate the impact of each exposure on unintended pregnancy both in the presence and the absence of violence. The final models for each form of reproductive control utilized the full analytic sample and included an indicator term reflecting exposure to both partner violence and the form of reproductive control under consideration. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9 (SAS II. SAS, 9 ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2003).

3. Results

Seventy-six percent of the sample were 24 years of age or younger. Consistent with the location of family planning clinics in neighborhoods serving communities of color, over three quarters of the sample identified themselves as non-White, with 16% not born in the United States. Sixty-five percent reported being in a serious relationship, married, or cohabiting (Table 1).

Table 1.

Associations of demographic characteristics with partner violence, pregnancy coercion, birth control sabotage, and unintended pregnancy (n=1278)

| %* | % Partner violence † |

% Pregnancy coercion † |

% Birth control sabotage † |

% Unintended pregnancy † |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | (100) | 53.4 | 19.1 | 15.0 | 40.9 |

| Age / years | |||||

| 16–20 | 42.6 | 51.0 | 17.6 | 11.7 | 27.0 |

| 21–24 | 33.4 | 50.4 | 19.9 | 15.9 | 47.3 |

| 25–29 | 23.9 | 62.1 | 20.6 | 19.3 | 56.6 |

| Chi-square p value | 0.002 | 0.498 | 0.010 | <0.0001 | |

| Race | |||||

| White | 22.4 | 56.3 | 13.3 | 7.3 | 36.7 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 28.1 | 54.6 | 25.9 | 27.0 | 49.9 |

| Hispanic | 29.9 | 50.0 | 16.8 | 11.5 | 34.0 |

| Multiracial | 7.1 | 62.6 | 27.5 | 15.4 | 48.4 |

| Asian/ Other | 12.5 | 48.8 | 15.0 | 9.4 | 40.0 |

| Chi-square p value | 0.114 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Relationship(s) | |||||

| Single/Dating | 32.3 | 55.0 | 22.5 | 21.8 | 43.6 |

| Serious relationship |

45.5 | 53.0 | 17.0 | 11.7 | 37.0 |

| Married/cohabiting | 19.4 | 50.0 | 17.7 | 11.3 | 44.4 |

| Divorced/Widowed | 2.7 | 68.6 | 22.9 | 14.3 | 48.6 |

| Chi-square p value | 0.185 | 0.149 | <0.0001 | 0.074 | |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school |

1.81 | 39.1 | 34.8 | 26.1 | 34.8 |

| Some high school | 20.8 | 54.3 | 16.6 | 12.1 | 35.9 |

| High school graduate |

34.0 | 50.1 | 18.0 | 16.4 | 41.8 |

| Some college | 32.7 | 55.8 | 21.9 | 12.7 | 43.8 |

| College graduate | 10.8 | 57.7 | 15.3 | 19.7 | 38.7 |

| Chi-square p value | 0.216 | 0.078 | 0.068 | 0.291 | |

| Country of origin | |||||

| U.S. Born | 83.9 | 55.9 | 20.2 | 15.8 | 42.2 |

| Born outside U.S. | 16.1 | 41.5 | 13.7 | 10.7 | 33.7 |

| Chi-square p value | 0.0001 | 0.030 | 0.063 | 0.024 |

Column %;

row %.

Over half of the sample (53.4%) reported having experienced physical or sexual violence from an intimate partner. Pregnancy coercion was reported by approximately 1 in 5 (19.1%), and birth control sabotage was reported by approximately 1 in 7 (15.0%). More than 2 in 5 (40.9%) had experienced at least one unintended pregnancy.

As expected, due to greater exposure to more relationships as people age, reports of lifetime experiences of intimate partner violence, birth control sabotage, and unintended pregnancy were highest among older women. Even among the youngest in this sample (ages 16–20 years), however, over half had experienced partner violence, 18% pregnancy coercion, and 12% birth control sabotage. Non-Hispanic Black and multi-racial women were most likely to report pregnancy coercion, birth control sabotage, and unintended pregnancy. Birth control sabotage was most common among women describing themselves as single or dating more than one person. U.S. born women were more likely to report violence from a partner, unintended pregnancy, and pregnancy coercion relative to immigrant counterparts.

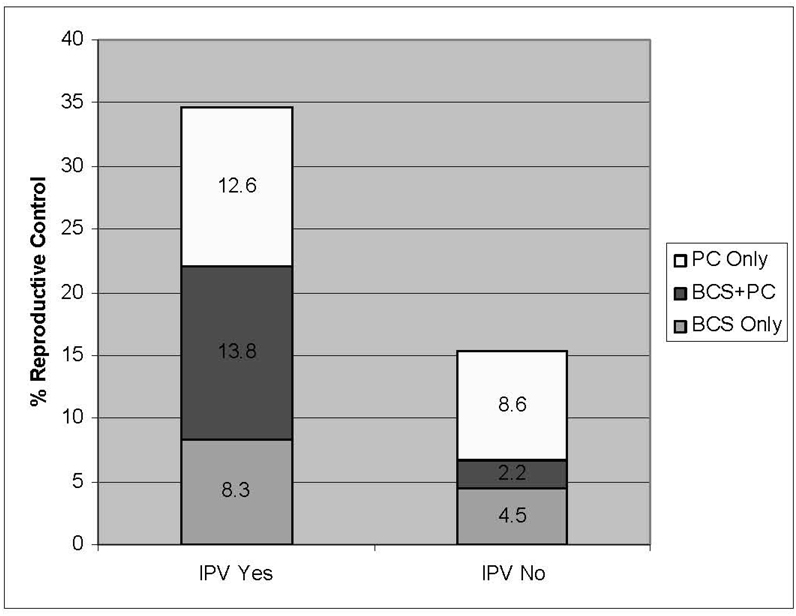

Fig. 1 illustrates the overlap of partner violence, pregnancy coercion, and birth control sabotage. Approximately a third (35%; 237 of 683) of women reporting partner violence also reported either pregnancy coercion or birth control sabotage, in contrast to only 15% (91 of 595) of those who never reported violence reporting reproductive control of either form. Of the 191 women reporting birth control sabotage, 79% (151 women) also reported partner violence and just over half (56% or 107 women) also reported pregnancy coercion. Of the 244 women reporting pregnancy coercion, 74% (180 women) also reported partner violence, and 44% (107 women) reported birth control sabotage. Of note, the co-occurrence with reproductive control did not differ between physical and sexual violence victimization when these partner violence experiences were examined separately (results available upon request). In unadjusted models, each of these exposures (reproductive control, pregnancy coercion only, birth control sabotage only, and partner violence) was associated with unintended pregnancy (Table 2).

Fig.1.

Overlap of lifetime physical or sexual partner violence victimization, pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage among female clients seeking family planning services

Intimate partner violence (IPV) history reported N (% total sample) = 683 (53.4%)

No IPV history reported N (% total sample) = 595 (46.6%)

PC = pregnancy control

BCS = birth control sabotage

Table 2.

Unintended pregnancy distribution across exposure to reproductive control and intimate partner violence (n=1278)

| Unintended pregnancy among exposed %* |

Unintended pregnancy among unexposed %* |

Crude OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Any reproductive control |

51.8 | 37.5 | 1.79 (1.39, 2.31) |

| Pregnancy coercion |

54.5 | 37.6 | 1.99 (1.50, 2.63) |

| Birth control sabotage |

54.5 | 38.5 | 1.91 (1.40, 2.61) |

| Intimate partner violence |

45.7 | 35.3 | 1.54 (1.23, 1.93) |

Row %.

In a multivariate model (Model 1) adjusted for age, ethnicity, clinic site, and immigrant status, reproductive control (composite of pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage) and partner violence were both associated with unintended pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 1.60, 95% CI 1.22, 2.09; AOR 1.29, 95% CI 1.01, 1.65, respectively; Table 3). In analyses stratified by exposure to partner violence (Model 2), reproductive control was associated with unintended pregnancy among those exposed to partner violence (AOR 2.02, 95% CI 1.45, 2.82), but not among those reporting no violence (AOR 1.00, 95% CI 0.62, 1.63). In the third model containing an interaction term representing exposure to both partner violence and reproductive control, the main effect of partner violence (AOR 1.11, 95% CI 0.84, 1.46) represents the effect of partner violence in the absence of reproductive control, and the main effect of reproductive control represents the effect of reproductive control in the absence of violence (AOR 1.01, 95% CI 0.62, 1.63). The combined effect of both partner violence and reproductive control increased the odds of unintended pregnancy almost two-fold (AOR 1.99, 1.11, 3.58).

Table 3.

Associations of reproductive control with unintended pregnancy

| Reproductive control | Pregnancy coercion | Birth control sabotage | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reproductive control AOR (95% CI) |

Partner violence AOR (95% CI) |

Both AOR (95% CI) |

Pregnancy coercion AOR (95% CI) |

Partner violence AOR (95% CI) |

Both AOR (95% CI) |

Birth control sabotage AOR (95% CI) |

Partner violence AOR (95% CI) |

Both AOR (95% CI) |

|

|

Model 1* (multivariate) Entire sample |

1.60 (1.22, 2.09) |

1.29 (1.01, 1.65) |

-- |

1.83 (1.36, 2.46) |

1.29 (1.02, 1.65) |

-- |

1.58 (1.14, 2.20) |

1.32 (1.04, 1.68) |

-- |

|

Model 2* (stratified) Among Violence YES N = 683 |

2.02 (1.45, 2.82) |

-- |

-- |

2.35 (1.63, 3.38) |

-- |

-- |

1.77 (1.21, 2.59) |

-- |

-- |

| Among Violence NO N = 595 |

1.00 (0.62, 1.63) |

-- | -- | 1.03 (0.59, 1.81) |

-- | -- | 1.11 (0.56, 2.20) |

-- | -- |

|

Model 3* (interaction) Entire sample |

1.01 (0.62, 1.63) |

1.11 (0.84, 1.46) |

1.99 (1.11, 3.58) |

1.05 (0.60, 1.83) |

1.14 (0.88, 1.48) |

2.22 (1.14, 4.32) |

1.11 (0.56, 2.19) |

1.26 (0.97, 1.62) |

1.60 (0.73, 3.48) |

Adjusted for age, ethnicity, recruitment site, and immigrant status as well as all variables listed in the row.

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

Similar patterns were observed for each distinct component of reproductive control. Pregnancy coercion and partner violence demonstrated independent associations with unintended pregnancy (AOR 1.83, 95% CI 1.36, 2.46; AOR 1.29, 95% CI 1.02, 1.65, respectively). Stratified analyses indicated that the impact of pregnancy coercion was, again, concentrated only among those also exposed to partner violence (AOR 2.35, 95% CI 1.63, 3.38 for those experiencing partner violence vs. AOR 1.03, 95% CI 0.59, 1.81 among those not exposed to such abuse). The final model containing the interaction term indicated that neither pregnancy coercion in the absence of partner violence (AOR 1.05, 95% CI 0.60, 1.83) nor violence in the absence of pregnancy coercion (AOR 1.14, 95% CI 0.88, 1.48) were significantly associated with unintended pregnancy. The relationship of pregnancy coercion with unintended pregnancy in the presence of partner violence was approximately two fold greater compared with pregnancy coercion in the absence of violence (AOR 2.22; 95% CI 1.14, 4.32).

Birth control sabotage and partner violence demonstrated independent associations with unintended pregnancy (AOR 1.58, 95% CI 1.14, 2.20; AOR 1.32, 95% CI 1.04, 1.68, respectively). In stratified models, birth control sabotage was also associated with unintended pregnancy in the presence of partner violence (AOR 1.77, 95% CI 1.21, 2.59). However, the interaction term representing exposure to both birth control sabotage and partner violence was not statistically significant (AOR 1.60, 95% CI 0.73, 3.48).

4. Discussion

The current study documents a high prevalence of partner violence, pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage among young women attending family planning clinics. To our knowledge, this is the first quantitative description of reproductive control (pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage) in the family planning and domestic violence literature. These under-recognized behaviors are likely to increase risk for unintended pregnancy. Moreover, associations of intimate partner violence with unintended pregnancy observed in prior studies [6–14] may be at least partially explained by experiences of pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage.

Pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage were reported in the absence of physical or sexual partner violence in 7% (91 of 1278 women) of this clinic-based sample, suggesting women’s experiences of reproductive controlling behaviors by men who do not physically or sexually abuse them are less common than among women who have experienced partner violence. One explanation may be that reproductive control by male partners precedes physical and sexual abuse; longitudinal research is needed to determine if such a chronology exists. Moreover, the current assessment was limited to lifetime exposure, with little detail available concerning frequency and severity of reproductive controlling behaviors; thus, the lack of association of reproductive control with unintended pregnancy observed among those not victimized by partner violence may reflect qualitative differences in experiences of reproductive control among those not also abused. However, the current findings should not be interpreted as determining that reproductive control of women by men in the absence of violence is not detrimental to women’s health and well-being; future studies should examine the broader effects of this type of male partner control in women’s lives. Conversely, approximately three quarters of women reporting pregnancy coercion or birth control sabotage also reported a history of partner violence (237 of the 328 women reporting reproductive control), with risk for unintended pregnancy doubled for this group. Future studies should examine these phenomena to clarify the relative chronology of reproductive control and partner violence, and how they combine in women’s lives to affect risk for unintended pregnancy.

The high prevalence of partner violence in family planning clinics found in this study (over half of women and girls ages 16–29 years) is consistent with prior studies that have documented high rates of violence in intimate relationships among female clients presenting for sexual and reproductive health services [25, 26]. Likely related to the reproductive health concerns associated with abuse and violence in intimate relationships, women victimized by violence also have high rates of seeking care at family planning and sexual health clinics [14, 29]. The present findings underscore the potential utility of family planning clinics to provide intervention programs to reduce harm related to reproductive control and partner violence, and to serve as a bridge to other services for the large numbers of young women who are affected by this violence.

This study describes pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage as specific experiences that pose increased risk for unintended pregnancy. The findings suggest that pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage may be an aspect of partner violence that, given its relevance to reproductive health, should be identified by providers in clinical settings. As simply screening for physical or sexual violence will not necessarily identify women experiencing pregnancy coercion or birth control sabotage, providers should ask specifically about these experiences. Screening for pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage will allow providers to assist clients in identifying strategies to reduce their risk for unintended pregnancy, including “invisible” forms of birth control such as injectable and intrauterine contraceptives as well as easy access to emergency contraception. In addition, providers must consider the overlap between pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage with partner violence and be prepared to connect women to violence-related support services.

The findings from the present study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the investigation precludes conclusions concerning temporality regarding associations observed among pregnancy coercion, birth control sabotage, and intimate partner violence with unintended pregnancy. Similarly, the measures of lifetime prevalence prevent any temporal ordering of these variables. Longitudinal studies with greater specificity about partner violence and reproductive control occurring in which relationships are necessary to better understand the associations described here. Findings from this convenience sample from five family planning clinics in one Northern California region with similar demographics across clinics also cannot be generalized to all family planning clinic clients.

Comprehensive screening in clinical settings for the prevalent experiences of pregnancy coercion, birth control sabotage, and partner violence should be considered a priority, particularly in the context of family planning and related programmatic efforts to reduce unintended pregnancy. Such screening may facilitate the critical work of addressing barriers to contraception among affected women and girls so as to reduce their elevated risk for unintended pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the staff of Planned Parenthood Shasta Diablo Affiliate for their invaluable support with this study, specifically the clinics located in the Richmond, Vallejo, Antioch, and Fairfield communities. Heather Anderson, Jenna Burton, Shadi Hajizadeh, Marian Parsons, and Alicia Riley provided invaluable research assistance. In addition, we wish to thank Lisa James, Director of Health, Family Violence Prevention Fund, and Yali Bair, Vice President Planned Parenthood Affiliates of California, for their input on this manuscript.

Funding: Funding sources for this study are the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R21 HD057814-02 to Miller and Silverman); UC Davis Health System Research Award to Miller; and Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health award to Miller (BIRCWH, K12 HD051958; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Office of Research on Women’s Health, Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institute of Aging).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Black MC, Breiding MJ. Adverse health conditions and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence - United States, 2005. [accessed December 1, 2009];Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008 http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5705a1.htm. [PubMed]

- 2.Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci LA, Hathaway JE. Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. JAMA. 2001;286:572–579. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamberger LK, Ambuel B. Dating violence. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1998;45:381–390. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard D, Wang M, Yan F. Psychosocial factors associated with reports of physical dating violence among U.S. adolescent females. Adolescence. 2007;42:311–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catalano S. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Intimate partner violence in the United States. 2007

- 6.Cripe SM, Sanchez SE, Perales MT, Lam N, Garcia P, Williams MA. Association of intimate partner physical and sexual violence with unintended pregnancy among pregnant women in Peru. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;100:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao W, Paterson J, Carter S, Iusitini L. Intimate partner violence and unplanned pregnancy in the Pacific Islands Families Study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;100:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman JG, Gupta J, Decker MR, Kapur N, Raj A. Intimate partner violence and unwanted pregnancy, miscarriage, induced abortion, and stillbirth among a national sample of Bangladeshi women. BJOG. 2007;114:1246–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephenson R, Koenig MA, Acharya R, Roy TK. Domestic violence, contraceptive use, and unwanted pregnancy in rural India. Stud Fam Plann. 2008;39:177–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pallitto CC, O'Campo P. The relationship between intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy: analysis of a national sample from Colombia. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2004;30:165–173. doi: 10.1363/3016504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Donnell L, Agronick G, Duran R, Myint UA, Stueve A. Intimate partner violence among economically disadvantaged young adult women: associations with adolescent risk-taking and pregnancy experiences. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;41:84–91. doi: 10.1363/4108409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lang DL, Salazar LF, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Mikhail I. Associations between recent gender-based violence and pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, condom use practices, and negotiation of sexual practices among HIV-positive women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:216–221. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31814d4dad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gazmararian JA, Petersen R, Spitz AM, Goodwin MM, Saltzman LE, Marks JS. Violence and reproductive health: current knowledge and future research directions. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4:79–84. doi: 10.1023/a:1009514119423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hathaway JE, Mucci LA, Silverman JG, Brooks DR, Mathews R, Pavlos CA. Health status and health care use of Massachusetts women reporting partner abuse. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:302–307. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The effects of an abusive primary partner on the condom use and sexual negotiation practices of African-American women. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1016–1018. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams M, Bowen A, Ross M, Timpson S, Pallonen U, Amos C. An investigation of a personal norm of condom-use responsibility among African American crack cocaine smokers. AIDS Care. 2008;20:218–227. doi: 10.1080/09540120701561288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sales JM, Salazar LF, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Rose E, Crosby RA. The mediating role of partner communication skills on HIV/STD-associated risk behaviors in young African American females with a history of sexual violence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:432–438. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.5.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teitelman AM, Ratcliffe SJ, Morales-Aleman MM, Sullivan CM. Sexual relationship power, intimate partner violence, and condom use among minority urban girls. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23:1694–1712. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davila YR, Brackley MH. Mexican and Mexican American women in a battered women's shelter: barriers to condom negotiation for HIV/AIDS prevention. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1999;20:333–355. doi: 10.1080/016128499248529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shrier LA, Pierce JD, Emans SJ, DuRant RH. Gender differences in risk behaviors associated with forced or pressured sex. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:57–63. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McFarlane J, Malecha A, Watson K, et al. Intimate partner sexual assault against women: frequency, health consequences, and treatment outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:99–108. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000146641.98665.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, McCree DH, Harrington K, Davies SL. Dating violence and the sexual health of black adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2001;107:e72. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.5.e72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller E, Decker MR, Reed E, Raj A, Hathaway JE, Silverman JG. Male partner pregnancy-promoting behaviors and adolescent partner violence: findings from a qualitative study with adolescent females. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center for Impact Research. Chicago, IL: Center for Impact Research; 2000. Domestic violence and birth control sabotage: A report from the Teen Parent Project. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rickert VI, Wiemann CM, Harrykissoon SD, Berenson AB, Kolb E. The relationship among demographics, reproductive characteristics, and intimate partner violence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1002–1007. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.126649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keeling J, Birch L. The prevalence rates of domestic abuse in women attending a family planning clinic. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2004;30:113–114. doi: 10.1783/147118904322995500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale: Development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Iss. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koss MP, Gidycz CA. Sexual Experiences Survey: reliability and validity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:422–423. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Decker MR, Silverman JG, Raj A. Dating violence and sexually transmitted disease/HIV testing and diagnosis among adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e272–e276. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]