Abstract

The complex morphologies of mineralised collagen fibrils are regulated through interactions between the collagen matrix and non-collagenous extracellular proteins. In the present study, polyvinylphosphonic acid, a biomimetic analogue of matrix phosphoproteins, was synthesised and confirmed with FTIR and NMR. Biomimetic mineralisation of reconstituted collagen fibrils devoid of natural non-collagenous proteins was demonstrated with TEM using a Portland cement-containing resin composite and a phosphate-containing fluid in the presence of polyacrylic acid as sequestration, and polyvinylphosphonic acid as templating matrix protein analogues. In the presence of these dual biomimetic analogues in the mineralisation medium, intrafibrillar and extrafibrillar mineralisation via bottom-up nanoparticle assembly based on the nonclassical crystallisation pathway could be identified. Conversely, only large mineral spheres with no preferred association with collagen fibrils were observed in the absence of biomimetic analogues in the medium. Mineral phases were evident within the collagen fibrils as early as 4 hours after the initially-formed amorphous calcium phosphate nanoprecursors were transformed into apatite nanocrystals. Selected area electron diffraction patterns of highly mineralised collagen fibrils were nearly identical to those of natural bone, with apatite crystallites preferentially aligned along the collagen fibril axes.

Keywords: extrafibrillar mineralisation, intrafibrillar mineralisation, matrix protein analogues, reconstituted collagen fibrils, tissue engineering materials

1. Introduction

From earlier studies that demonstrated predominantly extrafibrillar mineralisation around collagen fibrils [1,2] to more recent studies that verified intrafibrillar mineralisation with collagen fibrils [3,4], much progress has been made in the understanding of the biomineralisation process over the past decade. As collagen fibrils are the basic building blocks of mineralised hard tissues [5–8], the processes that contribute to their biomineralisation should be identified. As the collagen matrix does not initiate mineralisation on its own [9], mineralisation is regulated through complex interactions between the collagen matrix and non-collagenous proteins [10–13]. Ex vivo studies have demonstrated that acidic non-collagenous proteins control crystal nucleation and the dimension, order and hierarchy of apatite deposition within mineralised hard tissues [10,14–16]. However, the therapeutic use of native or recombinant extracellular matrix proteins for in-situ biomineralisation is economically prohibitive. Thus, research scientists have elected to using polyanionic macromolecules to mimic the functional domains of these naturally-occurring proteins [1–4,14].

Apatite deposition within collagen fibrils appears to be regulated by two important steps. The first step is sequestration of calcium phosphates into nanoscopic compartments which is referred to as polymer-stabilised amorphous mineral phases [17–19]. Recent studies have shown that the first mineral formed in mineralised collagenous tissues is a liquid phase of amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) [20–23] that canbe drawn into the nanoscopic gaps of collagen fibrils by capillary action [3,18,24,25]. The subsequent step relies on the role of matrix phosphoproteins in providing templates to control the dimension and hierarchy of apatite deposition within collagen fibrils [26,27]. Incorporation of a biomimetic analogue with sequestering function into a mineralisation medium helps stabilise ACP precursors in their required nanoscale dimensions [25,28,29]. The use of phosphoprotein biomimetic analogues further serve as templates that guide the self-assembly of the stabilised nanoprecursors along specific sites on and within collagen fibrils [30]. Previous studies have demonstrated that polyanionic macromolecules can initiate amorphous to crystalline phase transition in a controlled manner [31,32]. These phenomena are thought to proceed via the non-classical crystallization pathways of bottom-up nanoparticle assembly and mesocrystalline transformation [33,34].

A biomimetic mineralisation strategy has been developed based on the binding of two biomimetic analogues, polyacrylic acid and polyvinylphosphonic acid (PVPA) to collagen fibrils so that the doped collagen can guide the scale and distribution of apatites [35]. A low molecular weight polyacrylic acid is used to create metastable ACP nanoprecursors [36] in the presence of calcium and phosphate ions at a high pH [37], while PVPA mimics the negative charges of phosphoproteins such as DMP1, bone sialoprotein and phosphophoryn [15,28,30]. The bound analogues present multiple negatively-charged sites for calcium binding at both intrafibrillar and interfibrillar locations [16]. In addition to the biomimetic analogues, set white Portland cement is used for sustained release of hydroxyl and calcium ions. Set Portland cement is a bioactive cement that releases calcium hydroxide and interacts with phosphate-containing fluid to produce carbonated apatites via ACP phases [37]. A high pH of the mineralisation medium is required for auto-transformation of ACP into a more stable apatite phase without the participation of an octacalcium phosphate phase that is formed at pH values less than 9.25 [38].

The current study was designed to achieve a high level of control of mineralisation kinetics according to the aforementioned protocol. We coated transmission electron microscopy grids with reconstituted type I collagen fibrils, and then attempted to mineralize both the intrafibrillar and extrafibrillar compartments of the collagen scaffolds. This system consisted of five components: the two biomimetic analogues, 1) polyacrylic acid and 2) PVPA were both dispersed in a simulated body fluid (SBF) containing 3) phosphate ions. Set Portland cement provided sustained release of 4) calcium and 5) hydroxyl ions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Synthesis of PVPA

Vinylphosphonic acid (11.44 g, TCI America, Portland, OR, USA) was dissolved in ethyl acetate (55 g, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in a round bottom flask connected to a reflux condenser. Benzoyl peroxide (0.172 g, Sigma-Aldrich) was then added to the mixture and kept for 4 hours in a water bath at 90°C. The white precipitation was washed with ethyl acetate and lyophilized. The dried precipitate (66% yield) was characterised using attenuated total reflection-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) and 1H and 31P nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Infrared spectra were collected at 4 cm−1 resolution using 32 scans (Nicolet 6700, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The 1H and 31P NMR spectra were recorded in solution (5 wt% in D2O) with a Varian Inova spectrometer (Model 400-MR, Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) at 400 and 161 MHz, respectively. The 1H NMR spectra were referenced on internal sodium 3-(trimethylsilyl)propionate-2,2,3,3-d4 (chemical shift = 0 ppm). The 31P NMR spectra were referenced on external H3PO4 (chemical shift = 0 ppm).

2.2. Resin composite with a sustained releasing source of calcium and hydroxyl ions

A light-polymerisable hydrophilic resin blend consisting of 70 wt% bisphenol A diglycidyl ether dimethacrylate (Bis-GMA; Esstech, Essington, PA, USA), 28.75 wt% 2-hydroxylethyl methacrylate (HEMA; Esstech), 1 wt% ethyl N,N-dimethyl-4-aminobenzoate (EDMAB; Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.25 wt% camphorquinone (CQ; Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared. The hydrophilicity of the resin blend was defined in terms of its Hoy’s component solubility parameters (δ) by summing the molar attractive constants of each repeating functional group in the polymer according to the method of Barton [39]: δd for dispersive forces, 14.0; δp for polar forces, 13.1; δh for hydrogen bonding forces, 10.8. All intermolecular attractive forces were summated to yield a total cohesive energy density (δt) that is equivalent to a Hildebrand’s solubility parameter of 22.0 MPa1/2.

Set white Portland cement (Lehigh Cement Company, Allentown, PA, USA) was used as a sustained releasing source of calcium and hydroxyl ions. The cement was mixed with deionised water in a 0.35:1 water-to-powder ratio and allowed to set and aged at 100% relative humidity for one week. The set Portland cement was reduced to a fine powder in a planetary ball mill (PM 100; Retsch, Newtown, PA, USA) using a zirconia jar and grinding balls and further sieved to exclude particles that were larger than 5 μm in diameter. Different amounts of the set Portland cement powder were mixed with silanised colloidal silica (OX-50; kindly provided by Bisco, Inc., Schaumburg, IL, USA) and homogenised with the hydrophilic resin blend to produce four experimental versions of calcium and hydroxyl ion-releasing hybrid composites (Table I).

Table I.

Composition of the four experimental versions of calcium and hydroxyl ion-releasing resin composites

| Composite version | Set Portland cement Powder (wt%) | Silanized colloidal silica (wt%) | Hydrophilic neat resin blend (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 35 | 5 | 60 |

| II | 30 | 10 | 60 |

| III | 45 | 5 | 50 |

| IV | 40 | 10 | 50 |

The experimental resin composites were placed in Teflon molds to form disks 6.0 ± 0.1 mm in diameter and 0.8 ± 0.02 mm thick. The exposed surfaces were covered with Mylar polyester strips to exclude atmospheric oxygen and the composite was polymerised at 450 nm using a quartz-tungsten-halogen light-curing unit operated at 600 mW/cm2 for 40 sec. After removing the disk from the mold, light polymerisation was repeated on the bottom surface of the disk. For each experimental resin composite, 10 resin disks were placed in a closed glass container containing 10 mL of deionised water (pH 6.46). Release of hydroxyl and calcium ions from each resin composite was measured respectively using a pH meter and a calcium ion activity electrode for a period of 32 days and expressed respectively as the pH value for hydroxyl ion release and in mM/L for calcium ion release. Based on their ion-releasing profiles and handling characteristics, one of the four experimental resin composites was selected for the subsequent parts of the experiments.

2.3. Interaction of the selected ion-releasing composite with a phosphate source

A simulated body fluid (SBF) was prepared by dissolving 136.8 mM NaCl, 4.2 mM NaHCO3, 3.0 mM KCl, 1.0 mM K2HPO4·3H2O, 1.5 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 2.5 mM CaCl2 and 0.5 mM Na2SO4 in deionised water and adding 3.08 mM sodium azide to prevent bacterial growth. The SBF was buffered to pH 7.4 with 0.1 M Tris Base and 0.1 M HCl and filtered through a 0.22 μm Millipore filter. The SBF acts as the phosphate source for the formation of calcium phosphate phases. Twenty 6 mm-diameter resin disks were prepared from the selected experimental hydroxyl and calcium ion-releasing composite in the manner previously described and immersed in 40 mL of the SBF for 10 days. The turbid solution containing a white precipitate was centrifuged and the precipitate was re-suspended in deionised water and re-centrifuged. The purification procedure was repeated twice to eliminate dissolved salts from the SBF prior to lyophilisation of the precipitate. Part of the freeze-dried powder was sputtered-coated with gold/palladium for examination with a field emission-scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM; XL-30 FEG; Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at 5 KeV. The rest of the powdered precipitate was analysed as-prepared (i.e. without further sintering) by X-ray diffraction (Rigaku America, Woodlands, TX, USA) using Ni-filtered Cu Kα radiation (30 KeV, 20 mA), in the 2θ range of 20°–60°, with a scan rate of 4°/min, and a sampling interval of 0.02°.

2.4. Self-assembly of collagen fibrils

Lyophilised type I collagen powder derived from calf skin (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved overnight in 0.1 M acetic acid (pH 3.0) containing 2 μL/mL phenol red at 4°C to obtain a 0.1–0.2 wt% collagen solution. Eighty μL droplets of the collagen solution were placed on an inert polyethylene substrate in a humidity chamber and a 400-mesh carbon- and formvar-coated Ni TEM grid (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) was placed on top of each droplet. A Petri dish containing 25% ammonium hydroxide solution (v/v) was placed inside the humidity chamber. The latter was sealed and the grids were incubated at 37°C for 3 hours until neutralisation of the collagen solution by ammonia vapor was evident by the colour change of the pH indicator. The ammonium hydroxide solution was removed and the collagen solution was left to gel by further incubation at 37°C for 21 hours. Cross-linking of the reconstituted collagen fibrils was performed by floating the collagen-coated grids upside down in 0.3 M 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride solution (pH adjusted to 5.5) for 4 hours. Confirmation of self-assembly of the collagen fibrils was performed by staining randomly selected grids with 1% uranyl acetate for 1 min and examining the stained grids with TEM (JEM-1230; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 110 kV.

2.5. Collagen mineralisation in the absence of biomimetic analogues

The SBF was used as the control mineralisation medium. Additional resin composite disks were prepared from the selected resin composite. One 30 μL drop of the SBF was placed on top of the composite disk. Two TEM grids containing the cross-linked reconstituted collagen fibrils were floated upside down on top of the droplet and sealed inside the humidity chamber. The grids were incubated for 4, 8, 16 and 24 hours (N = 6) in the humidity chamber at 37°C, retrieved at the designated time interval and examined without staining using the JEM-1230 TEM.

2.6. Collagen mineralisation in the presence of biomimetic analogues

The experiments were performed as in the control but with a cocktail of biomimetic analogues, consisting of 200–1000 ppm of the synthesised PVPA and polyacrylic acid (Mw 1800; Sigma-Aldrich) added to the SBF to produce a biomimetic mineralisation solution. Collagen-coated grids were similarly incubated for 4, 8, 16 and 24 hours (N = 6). After retrieval, each grid was dipped in and out of deionised water to remove loose precipitates and examined with TEM without further staining. Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) was performed to determine the nature of the calcium phosphate phase within the mineralised collagen fibrils.

3. Results

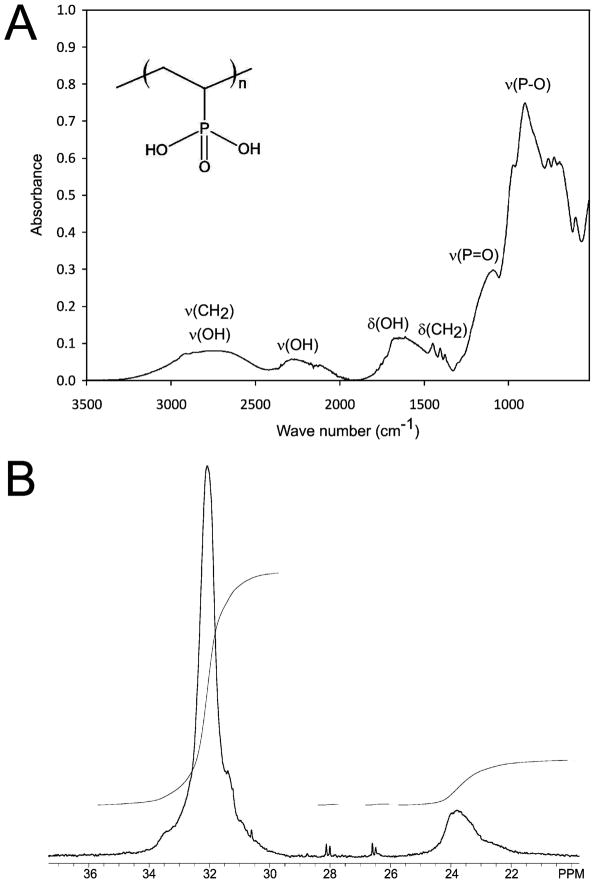

The infrared spectrum of PVPA (Fig. 1A) shows strong bands at 957-766 cm−1 that belongs to asymmetric stretching vibrations of the (P-O)H group and at 966 cm−1 that corresponds to P=0 stretching. The phosphonic acid group produces a broad band in the region of 1670-1600 cm−1 that corresponds to the –OH bending mode. The –OH stretching of the same group shows broad bands at 2900-2639 cm−1 and 2300-2190 cm−1 [40]. The results of 1H and 31P NMR spectra were: 1H NMR (D2O): δ = 2.2 (CH-P), 1.9-1.1 (CH2). 31P NMR (D2O): δ = 32.1. Both the 1H and 31P NMR spectra corresponded well with published data for PVPA [41,42]. An additional peak in the 31P NMR spectrum (δ = 23.8; Fig. 1B) corresponds to that of PVPA anhydride (up to 19 wt%) for precipitates measured immediately after dissolving in D2O [43]. Both 1H and 31P are nuclei of 100% natural abundance and high NMR sensitivity that can be applied to elucidate the PVPA structure by comparison of the chemical shift with known and published spectra.

Fig. 1.

A. Infrared spectrum of synthesised PVPA. B. 31P NMR spectrum of synthesised PVPA (δ = 32.1 ppm) and its anhydride (δ = 23.8 ppm).

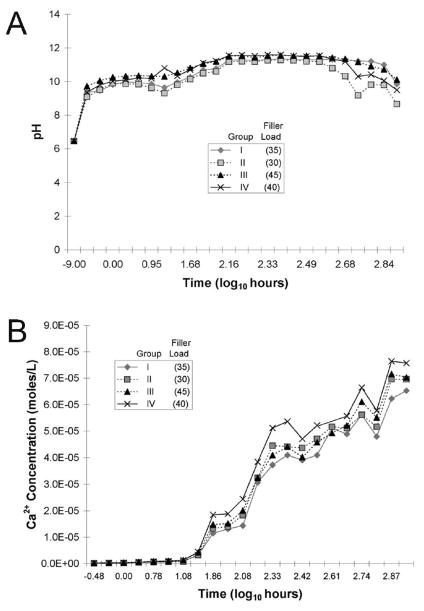

The composition of four experimental versions of calcium and hydroxyl ion-releasing resin composites is presented in Table I and the time-dependent changes in calcium ion concentration and pH from the four experimental polymerised composite disks are shown in Fig. 2. Similar pH changes (Fig. 2A) were observed from the four experimental resin composites after they were immersed in deionised water. The pH increased rapidly from that of deionised water (6.86) to above 9.5 within 1 hour and reached relatively constant values between 11.2–11.3 after 144 hours. These high pH values were maintained for two weeks before the values gradually declined after 336 hours. The final pH values at the end of the 32-day measurement period were between 9.0–10.1. The calcium release from the four experimental resin composites also exhibited a similar trend (Fig. 2B) in that there was a delay of 12 hour before a substantial amount of calcium ions were recorded. There was a greater amount of calcium ion release with increasing filler loads (i.e. 30% < 35% < 40% < 45%) of set Portland cement powder. Because of the similar ion release profiles, version IV of the experimental composites was selected for subsequent experiments based on its better flowability.

Fig. 2.

Release of calcium ions at a high pH from four experimental polymerised hydrophilic resin blends containing different filler loads (30–45 wt%) of set Portland cement. Disks produced from these Portland cement-containing resin blends provide the source of hydroxyl and calcium ions necessary for biomimetic mineralisation of the reconstituted collagen fibrils. A. Changes in pH with time due to the release of hydroxyl ions from the polymerised composite disks over a period of 32 days. B. Release of calcium ions from the polymerised composite disks over a period of 32 days. The composition of resin composites I – IV is shown in Table I.

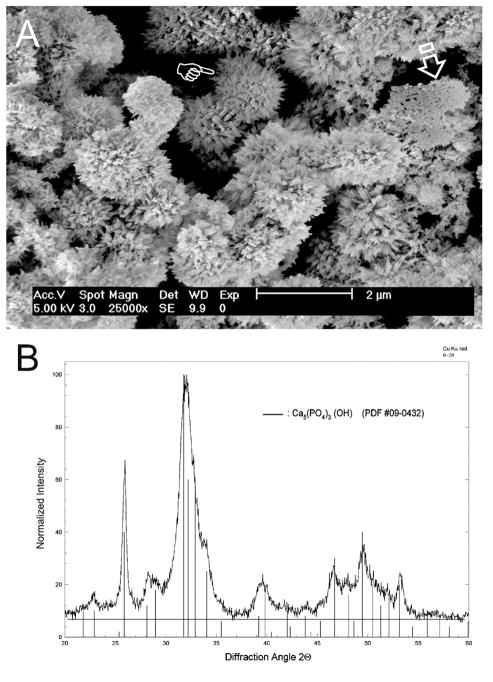

The calcium phosphate phase that was produced from the interaction of the selected experimental composite (version IV, Table I) with a SBF appeared morphologically as spherules of acicular crystallites (Fig. 3A). Those spherules varied between 0.2–1.5 μm in diameter. X-ray diffraction of the non-sintered, lyophilised precipitate (Fig. 3B) yielded a major single peak at 25.86 (°2Θ) that is characteristic of the 002 plane of apatite. The main peak at 31–34 (°2Θ), which represents the convolution of four peaks derived from the 211, 112, 300 and 202 planes of apatite remained unresolved and is characteristic of the low crystallinity observed in apatite prior to sintering [44].

Fig. 3.

Characterisation of the calcium phosphate precipitate retrieved from the interaction of the calcium and hydroxyl ion-releasing composite (experimental version IV) with the phosphate ion-containing simulated body fluid in the absence of biomimetic analogues. A. FE-SEM showing that spherules of acicular crystallites (pointer). Some flattened agglomerates of plate-like crystals were also observed (open arrow). B. X-ray diffraction pattern of the precipitate in the 2θ range from 20° to 60° indicates that it was composed of apatite.

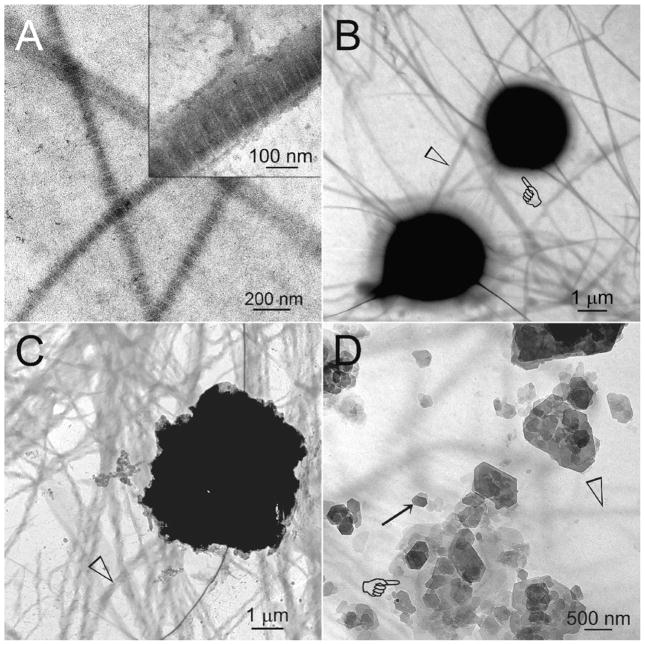

Stained TEM images of the intact, un-sectioned, cross-linked reconstituted collagen showed discrete collagen fibrils that were between 50–150 nm in their lateral diameter (Fig. 4A). Branching of the reconstituted collagen fibrils [45] were frequently observed (see Fig. 5A). These negatively-stained unmineralised collagen fibrils demonstrated banding patterns with ~67 nm periodicity (Fig. 4A) that is characteristic of self-assembled collagen fibrils [46]. Unstained TEM images of reconstituted fibrils that were retrieved from biomimetic analogue-free control medium contained large electron-dense spheres with a characteristic peripheral halo (4 hours; Fig. 4B). Many of those spheres appeared shrunken, revealing an irregular profile after immersion in the control medium for 8–16 hours (Fig. 4C). The large shrunken spheres appeared to have transformed into hexagonal crystalline plates at the end of 24 hours (Fig. 4D). Collagen fibrils from the control group did not mineralise at any time periods.

Fig. 4.

A. Low magnification TEM image of uranyl acetate negative-stained, cross-linked, reconstituted type I collagen fibrils (0.2 mg/mL) before they were subjected to biomimetic mineralisation. Inset: high magnification of a banded fibril showing the characteristic 67 nm periodicity of the stained, unmineralised collagen fibrils. B–D. Collagen fibrils from the control medium (open arrowheads) did not mineralise in the absence of biomimetic analogues. B. TEM grids retrieved after 4 hours from the control medium showed large (2–4 μm diameter) amorphous electron-dense spheres, each surrounded by a diffuse halo (pointer). C. In TEM grids that were retrieved between 8–16 hours, some of the electron-dense spheres appeared shrunken and exhibited spike-like features. D. Hexagonal crystalline plates (arrow) could additionally be identified from TEM grids retrieved after 24 hours of immersion in the control medium. The silhouette of a shrunken sphere with much reduced electron density (pointer) could be seen beneath some of the crystalline plates.

Fig. 5.

Unstained TEM of carbodiimide cross-linked, reconstituted type I collagen fibrils after the collagen-coated grids were left floating for 4 hours on top of a set Portland cement-containing resin disks that was covered with biomimetic analogues-containing simulated body fluid. A. Low magnification TEM showing electron-dense, amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) nanoprecursors droplets (arrow) that were formed in the vicinity of the unstained collagen fibrils (open arrowhead). B. High magnification of a cluster of partially-coalesced ACP droplets showing the fluidic nature of the initially formed nanoprecursors. C. High magnification of an unstained collagen fibril showing the first sign of intrafibrillar mineralisation of the fibril. The minerals were deposited in the form of electron-dense strands (arrow) within the collagen fibrils. Adjacent ACP nanoprecursors (open arrowhead) were imaged out of focus to enhance the mineralised fibril. D. Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) of the fibril shown in Fig. 5C revealed a diffuse pattern that is characteristic of the amorphous nature of the initially formed minerals.

Unstained reconstituted collagen fibrils that were retrieved from the biomimetic mineralisation medium after 4 hours demonstrated the presence of electron-dense, partially-coalesced spherical mineral phases scattered throughout the collagen matrix (Fig. 5A). At high TEM magnification, the fluidic nature of those amorphous phases was clearly revealed (Fig. 5B). Electron-dense strands that recapitulated the rope-like microfibrillar arrangement of the substructure of the collagen fibrils [47] could be vaguely discerned as early as 4 hours after mineralisation in the biomimetic medium (Fig. 5C). SAED of these mineral phases yielded an amorphous scatter of diffuse rings (Fig. 5D) that is characteristic of the fluidic nature of the ACP precursor phase [48].

Unstained reconstituted collagen fibrils that were retrieved from the biomimetic mineralisation assembly after 8 hours contained discrete electron-dense islands in which intrafibrillar mineralisation of the collagen fibrils and extrafibrillar mineralisation of the matrix adjacent to the fibrils could be simultaneously observed (Fig. 6A). While some of the intrafibrillar minerals retained their microfibrillar rope-like characteristics (Fig. 6B), others had been transformed into discrete nanocrystals within the fibrils (Fig. 6C), as demonstrated by the SAED appearance of diffraction ring patterns that are characteristic of poorly crystalline apatite (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Unstained TEM of cross-linked, reconstituted type I collagen fibrils after the collagen-coated grids were subjected to 8 hours of mineralisation. A. Low magnification image of the darker intrafibrillar and the lighter extrafibrillar mineralisation of the collagen fibrils. A distinct junction could be seen between the intrafibrillarly mineralised part and the unmineralised part of the same fibril (open arrow). ACP nanoprecursors (open arrowhead) could be seen in the vicinity of the collagen matrix. B. High magnification of Fig. 6A showing a dense arrangement of the rope-like intrafibrillar minerals (arrow) within the collagen fibril. Extrafibrillar nanocrystals were also formed around the fibril (open arrowhead). Open arrow: junction between the mineralised and unmineralised parts of the collagen fibril. C. High magnification of Fig. 6B showing intrafibrillar arrangement of nanocrystals within the mineralised part of the collagen fibrils. Silhouettes of the continuing unmineralised portion of the fibrils (between open arrows) show vague microfibrillar mineral strands (open arrowheads). D. SAED of the intrafibrillar nanocrystals revealed discrete ring patterns characteristic of apatite.

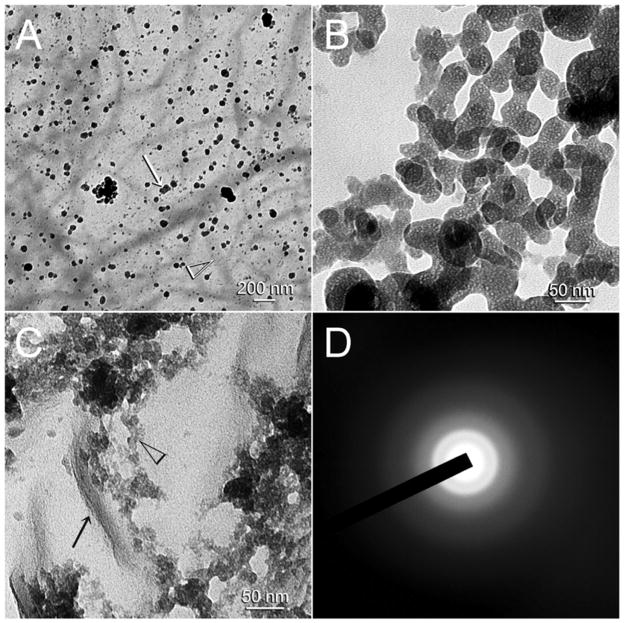

Collagen-coated grids that were retrieved after 16 and 24 hours from the biomimetic mineralisation medium demonstrated discrete islands of heavy mineralisation amidst regions with unmineralised collagen and matrices. Within those electron-dense islands, mineralisation was so heavy that evidence of both intrafibrillar and extrafibrillar mineralisation could only be discerned from the edge of the mineralised islands (Figs. 7A and B). Apatite nanocrystal formation within the collagen fibrils (Fig. 7C) was confirmed by the SAED showing arc-shaped patterns in some of the diffraction rings (Fig. 7D). Although the latter was suggestive of an orientated arrangement of nanocrystals, no definitive banded arrangement of the nanocrystals could be observed within the mineralised fibrils.

Fig. 7.

Unstained TEM of cross-linked, reconstituted collagen fibrils after they were subjected to 16 hours of mineralisation. A. Mineralisation occurred in the form of large, discrete islands of intrafibrillar (open arrowhead) and extrafibrillar mineralisation (asterisk). Pointer: areas containing unmineralised collagen fibrils. B. High magnification of Fig. 7A. As imaging was performed without sectioning, heavy intrafibrillar mineralisation within the collagen fibrils precluded identification of individual crystallites. Extrafibrillar minerals demonstrated a parallel alignment of nanocrystals. C. A less heavily mineralised edge of a mineralised island showing transformation of the initially formed intrafibrillar mineralised strands into needle-shaped nanocrystals within the collagen fibril (arrow). Open arrow: plate-like extrafibrillar nanocrystals. D. SAED of the region identified with an asterisk in Fig. 7C showing concentric ring patterns with arc-shaped patterns in the (002) and (211) planes that are indicative of the formation of apatite with a regular orientation (i.e. parallel to the longitudinal axis of the collagen fibril).

4. Discussion

To date, techniques involved in the synthesis of biomaterials and devices may be classified as top-down or bottom-up approaches [33,49]. Top-down approaches begin with a bulk material that incorporates nanoscale details, such as nanolithography and etching techniques. In the top-down approach, a biomaterial is generated by scaling down a complex entity into its component parts, such as paring of a virus particle down to its capsid to produce a viral cage. Bottom-up approaches are often affiliated with contemporary nanotechnological strategies and commence with one or more defined constituent elements such as molecular species that are organised into higher-order functional structures. Examples of bottom-up approaches include self-assembly, molecular patterning, templating and scaffolding methods. Self-assembly of collagen fibrils from collagen molecules represents an example of a bottom-up approach of biomaterial synthesis. Likewise, a biomimetic mineralisation strategy that involves the coalescence of polyacrylic acid-sequestered ACP nanoprecursors droplets and the use of templating molecules to guide the nucleation and growth of discrete apatite crystallites from amorphous precursors represents another example of a bottom-up approach in the synthesis of mineralised biomaterials at the nanoscopical scale.

Although mineralisation of natural collagen matrices derived from demineralised human hard tissues has been demonstrated using a similar biomimetic mineralisation strategy [35], it is not known if the mineralisation demonstrated in that study was partially attributed to the presence of remnant phosphoproteins that remain bound to collagen matrices after demineralisation [50,51]. As self-assembled purified collagen fibrils do not contain bound matrix proteins and cannot initiate mineralisation on their own without covalent cross-linking with phosphoproteins derived from other sources [16], we further challenged our biomimetic mineralisation strategy using reconstituted collagen fibrils deposited on TEM grids. We modified our previous strategy by incorporating the sustained releasing source of calcium and hydroxyl ions (i.e. set Portland cement particles) in a hydrophilic resin matrix. This modification was necessary to prevent absorption of mineralisation medium constituents by the highly porous, set Portland cement block. Conversely, the mineralisation medium could remain on top of a resin composite disk for a relatively long time if the assembly was stored in a closed system to prevent the medium from evaporation. While this modification was initially conceptualized out of necessity during the development of the present nanoscopic mineralisation model, the material may find potential use as a remineralising restorative material in dentistry. The phosphoprotein analogue PVPA was also synthesised in our laboratory by free radical polymerisation and was equally adept in terms of its templating function in collagen biomineralisation when compared to a commercial source of the polymer. As recombinant forms of phosphoproteins are still economically prohibitive for therapeutic uses and commercially available biomimetic analogues are relatively expensive, the ability to synthesise one’s own biomimetic analogues stretches research funds for future tissue engineering applications.

When mineralisation of the reconstituted collagen fibrils was performed in the absence of biomimetic analogues, only large mineral spheres were seen around the fibrils. The collagen fibrils per se did not mineralise at any time periods. This is analogous to the mineralisation results achieved when sodium trimetaphosphate was used as the exclusive analogue for chemical phosphorylation of collagen matrices [52]. In that study, the investigators did not use polyaspartic acid or polyacrylic acid for restricting the initially formed calcium phosphate phases to a nanoscale. Although sodium trimetaphosphate functions well as an alternative templating analogue that binds covalently to collagen fibrils at a high pH [52] to induce homogeneous apatite nucleation, only large spherical apatite clusters were formed around collagen fibrils in the absence of a sequestering analogue that stabilizes the ACP in the form of nanoprecursors (Tay FR, unpublished results). Conversely, when polyaspartic acid was used as the exclusive analogue for mineralisation of reconstituted collagen fibrils [4], the mineral phase remained as electron-dense, rope-like microfibrillar strands within the fibril without maturation into discrete apatite crystallites. This was probably due to the lack of a concomitant templating mechanism in that study design. The amorphous nanoprecursor phases formed in the presence of polyaspartic/polyacrylic acid have been referred as polymer-induced liquid-phase precursors [18]. The fluidic nature of calcium carbonate nanoprecursors enables them to coalesce and diffuse into the intercellular spaces of a multi-cell structure such as the sea urchin spine; solidification of that liquid phase produces a porous but continuous crystalline structure that conforms to cellular curvatures but lacks definitive crystalline planes [53]. Based on a similar mechanism, it is envisaged that filling of the internal compartments of a collagen fibril with a coalesced liquid mineral phase results in the manifestation of electron-dense mineral strands within the fibril the recapitulate the spiral, rope-like microfibrillar substructure of the fibril [47]. In the absence of a concomitant templating molecule, however, mineralisation probably remains in this inchoate state without further crystallite nucleation and growth [54]. Noncollagenous acidic matrix phosphoproteins are thought to bind to the collagen fibrils at specific sites such as the collagen bands adjacent to the hole zones of the fibril assembly [55]. The immobilised molecules present fixed anionic charged sites for attraction of the stabilised ACP nanoprecursors, facilitating their transformation into crystalline apatite phases at both intrafibrillar and extrafibrillar locations. The PVPA molecule has been perceived to function similarly as a templating molecule by binding to collagen fibrils. This probably explains why the initially formed electron-dense rope-like mineral phases (seen at 4 hours) within the collagen fibrils were eventually replaced by discrete apatite nanocrystals at a later stage (16 hours) of biomimetic mineralisation. Unlike binding of matrix phosphoproteins that occur at specific sites along a collagen fibril, binding of PVPA to collagen is probably non-specific as there are no preferential docking sites along the collagen molecule for attachment the PVPA molecule (Dr. Vaidyanathan, personal communication). This provides a plausible explanation why collagen banding was not identified even with heavy intrafibrillar mineralisation. Another possible reason is that the collagen fibrils were examined without sectioning, so that overlapping of the apatite platelets would preclude the observation of cross banding patterns even if they were present.

Although TEM examination of mineralised collagen matrices prepared by ultramicrotomy remains the gold standard in terms of optimal section thickness (ca. 70 nm) and resolution, direct examination of a single layer of reconstituted collagen (ca. 100 nm thick) deposited over a TEM grid offers the flexibility of evaluating the results of collagen mineralisation within 24 hours. In our previous TEM study [35], a 5–8 μm thick collagen matrix (i.e. 50–80 layers of collagen fibrils) required 2–3 months for complete mineralisation to occur. Thus, the most practical use of the nanoscopic model developed in the present study is initial screening of potential biomimetic analogues and determination of their optimal concentrations prior to the use of more labour intensive TEM techniques on thicker collagenous tissue sections. For example, we have been using the nanoscopic model to investigate the effect of cross-linking PVPA to the type I collagen with the use of carbodiimide and imidazole on mineralisation of collagen fibrils as a means of clinical translating the use of this phosphoprotein analogue by removing it from the mineralising medium. Based on this nanoscopic model, we have discovered other phosphoprotein analogues apart from PVPA that can be chemically cross-linked to collagen to achieve the same effect of collagen mineralisation. We are currently working on optimizing the concentrations of these alternative analogues, which would have taken us years to accomplish had we have relied on the original mineralisation model we developed using demineralised collagenous tissues. Nevertheless, the nanoscopic model remains a qualitative evaluation technique as deposition of the reconstituted collagen fibrils on the carbon-formvar film of the 400-mesh TEM grid was not uniform due to the influence of surface tension forces along the liquid-film interface during evaporation of the collagen solution. It may be helpful to pre-coat the carbon-formvar film on the TEM grids with a 0.01 mg/L solution of poly-L-lysine to produce an activated surface with positive electrostatic charges and allowing the grids to air-dry before using them for collagen reconstitution [56]. As proteins attach to the poly-L-lysine by electrostatic attraction, proteins containing negatively-charged groups such as carboxylate and hydroxyl groups will bind to the poly-L-lysine. Thus, it is theoretically possible to achieve a more uniform distribution of the reconstituted collagen fibrils. If successful, the present protocol may be adopted for quantitative assessment of the extent of collagen mineralisation.

As the biomechanical properties of mineralised collagenous tissues such as bone [57] and dentine [58] are dependent upon their intrafibrillar apatite minerals, it would be interesting to examine the modulus of elasticity of single, reconstituted and carbodiimide cross-linked collagen fibrils that are mineralised using the biomimetic mineralisation scheme to see if the mineralised collagen fibrils themselves exhibit sufficient load bearing properties for potential use as resorbable biomimetic mineralised collagen scaffolds with interconnecting porosities for tissue engineering applications [59,60]. Such a procedure will involve depositing the reconstituted cross-linked collagen fibrils on specialized silicon nitride perforated TEM grids with uniform 2.5 μm diameter circular holes and testing the bending modulus of the exposed section of a mineralised collagen fibril that spans across those holes using nanoscopic three-point bending with a modified stylus of an atomic force microscope [61].

With the advancement of rapid prototyping technologies [62], it may be possible to harness these techniques with the bottom-up intrafibrillar mineralisation approach by using a reconstituted collagen solution containing polyanionic analogues as bio-inks for inkjet printing of mineralisable 2-D and 3-D collagen scaffolds with precisely controlled internal porosities and cell-specific channel designs [63–65]. Presumably, this may be achieved by direct printing or via the use of sacrificial negative molds for casting of the biomimetic analogues-containing collagen solutions. Likewise, the bottom-up biomimetic mineralisation strategy may be adopted for creating intrafibrillarly-mineralised collagen coatings on the surfaces of orthopedic and dental implants, as a more biocompatible alternative to the use of hydroxyapatite coatings [66,67]. Understanding the basic processes involved in intrafibrillar mineralisation of reconstituted collagen fibrils creates new opportunities for the design of tissue engineering materials for hard tissue repair and regeneration.

5. Conclusions

A biomimetic mineralisation strategy based on the use of calcium and hydroxyl ion-releasing set Portland cement and a phosphate-containing SBF in the presence of polyacrylic acid and PVPA as respective sequestration and templating matrix protein analogues was successfully employed for mineralisation of self-assembled, cross-linked type I collagen fibrils. In the absence of biomimetic analogues in a mineralisation medium, there was no mineralisation of reconstituted collagen fibrils. Conversely, in the presence of biomimetic analogues in a mineralisation medium, intrafibrillar and extrafibrillar mineralisation could be identified. It is concluded that the interactions between collagen and biomimetic analogues lead to the formation of mineralised collagen fibrils that approximate the dimension and order of those found in natural mineralised tissues within 24 h. The nanoscopic protocol has immediate application as a rapid screening tool for potential biomimetic analogues for collagen mineralisation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grant R21 DE019213-01 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (PI. Franklin R. Tay). The colloidal silica employed in the study was a generous gift from Bisco Inc. We thank Michelle Barnes for her secretarial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bradt JH, Mertig M, Teresiak A, Pompe W. Biomimetic mineralization of collagen by combined fibril assembly and calcium phosphate formation. Chem Mater. 1999;11:2694–701. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang W, Liao SS, Cui FZ. Hierarchical self-assembly of nano-fibrils in mineralized collagen. Chem Mater. 2003;15:3221–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olszta MJ, Cheng X, Jee SS, Kumar R, Kim Y-Y, Kaufman MJ, et al. Bone structure and formation: a new perspective. Mat Sci Eng R. 2007;58:77–116. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deshpande AS, Beniash E. Bioinspired synthesis of mineralized collagen fibrils. Cryst Growth Des. 2008;8:3084–90. doi: 10.1021/cg800252f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Traub W, Arad T, Weiner S. Three-dimensional ordered distribution of crystals in turkey tendon collagen fibers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9822–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.9822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landis WJ, Song MJ. Early mineral deposition in calcifying tendon characterized by high voltage electron microscopy and three-dimensional graphic imaging. J Struct Biol. 1991;107:116–27. doi: 10.1016/1047-8477(91)90015-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiner S, Traub W. Bone structure: from angstroms to microns. Faseb J. 1992;6:879–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landis WJ, Hodgens KJ, Arena J, Song MJ, McEwen BF. Structural relations between collagen and mineral in bone as determined by high voltage electron microscopic tomography. Microsc Res Tech. 1996;33:192–202. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19960201)33:2<192::AID-JEMT9>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honda Y, Kamakura S, Sasaki K, Suzuki O. Formation of bone-like apatite enhanced by hydrolysis of octacalcium phosphate crystals deposited in collagen matrix. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2007;80:281–9. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boskey AL. Biomineralization: conflicts, challenges, and opportunities. J Cell Biochem. 1998;72:83–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(1998)72:30/31+<83::AID-JCB12>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boskey AL. Biomineralization: an overview. Connect Tissue Res. 2003;44:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Addadi L, Weiner S. Control and design principles in biological mineralization. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1992;31:153–69. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiner S, Addadi L. Design strategies in mineralized biological materials. J Mater Chem. 1997;7:689–702. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg HA, Warner KJ, Li MC, Hunter GK. Binding of bone sialoprotein, osteopontin and synthetic polypeptides to hydroxyapatite. Connect Tissue Res. 2001;42:25–37. doi: 10.3109/03008200109014246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter GK, Goldberg HA. Modulation of crystal formation by bone sialoproteins: role of glutamic acid-rich sequences in the nucleation of hydroxyapatite by bone sialoprotein. Biochem J. 1994;302:175–9. doi: 10.1042/bj3020175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saito T, Arsenault AL, Yamauchi M, Kuboki Y, Crenshaw MA. Mineral induction by immobilized phosphoproteins. Bone. 1997;21:305–11. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiner S, Sagi I, Addadi L. Choosing the crystallization path less traveled. Science. 2005;309:1027–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1114920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gower B. Biomimetic model systems for investigating the amorphous precursor pathway and its role in biomineralization. Chem Rev. 2008;108:4551–627. doi: 10.1021/cr800443h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pouget EM, Bomans PH, Goos JA, Frederik PM, de With G, Sommerdijk NA. The initial stages of template-controlled CaCO3 formation revealed by cryo-TEM. Science. 2009;323:1455–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1169434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crane NJ, Popescu V, Morris MD, Steenhuis P, Ignelzi MA., Jr Raman spectroscopic evidence for octacalcium phosphate and other transient mineral species deposited during intramembranous mineralization. Bone. 2006;39:434–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boskey AL. Amorphous calcium phosphate: the contention of bone. J Dent Res. 1997;76:1433–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760080501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Termine JD, Posner AS. Infrared analysis of rat bone: age dependency of amorphous and crystalline mineral fractions. Science. 1966;153:1523–5. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3743.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eanes ED. Amorphous calcium phosphate. Monogr Oral Sci. 2001;18:130–47. doi: 10.1159/000061652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cölfen H. Single crystals with complex form via amorphous precursors. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:2351–3. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olszta MJ, Odom DJ, Douglas EP, Gower LB. A new paradigm for biomineral formation: mineralization via an amorphous liquid-phase precursor. Connect Tissue Res. 2003;44:326–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuji T, Onuma K, Yamamoto A, Iijima M, Shiba K. Direct transformation from amorphous to crystalline calcium phosphate facilitated by motif-programmed artificial proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16866–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804277105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu SH. Bio-inspired crystal growth by synthetic templates. Top Curr Chem. 2007;271:79–118. [Google Scholar]

- 28.He G, Gajjeraman S, Schultz D, Cookson D, Qin C, Butler WT, et al. Spatially and temporally controlled biomineralization is facilitated by interaction between self-assembled dentin matrix protein 1 and calcium phosphate nuclei in solution. Biochemistry. 2005;44:16140–8. doi: 10.1021/bi051045l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang L, Webster TJ. Nanotechnology and nanomaterials: promises for improved tissue regeneration. Nano Today. 2009;4:66–80. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gajjeraman S, Narayanan K, Hao J, Qin C, George A. Matrix macromolecules in hard tissues control the nucleation and hierarchical assembly of hydroxyapatite. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1193–204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu GF, Yao N, Aksay IA, Groves JT. Biomimetic synthesis of macroscopic-scale calcium carbonate thin films. Evidence for a multistep assembly process. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:11977–85. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aizenberg J, Muller DA, Grazul JL, Hamann DR. Direct fabrication of large micropatterned single crystals. Science. 2003;299:1205–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1079204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong TS, Brough B, Ho CM. Creation of functional micro/nano systems through top-down and bottom-up approaches. Mol Cell Biomech. 2009;6:1–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niederberger M, Cölfen H. Oriented attachment and mesocrystals: non-classical crystallization mechanisms based on nanoparticle assembly. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2006;8:3271–87. doi: 10.1039/b604589h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tay FR, Pashley DH. Guided tissue remineralisation of partially demineralised human dentine. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1127–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liou SC, Chen SY, Liu DM. Manipulation of nanoneedle and nanosphere apatite/poly(acrylic acid) nanocomposites. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2005;73:117–22. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tay FR, Pashley DH, Rueggeberg FA, Loushine RJ, Weller RN. Calcium phosphate phase transformation produced by the interaction of the portland cement component of white mineral trioxide aggregate with a phosphate-containing fluid. J Endod. 2007;33:1347–51. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyer JL, Weatherall CC. Amorphous to crystalline phosphate phase transformation at elevated pH. J Colloidal Interface Sci. 1982;89:257–67. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barton AFM. Expanded cohesion parameters. In: Barton AFM, editor. Handbook of solubility parameters and other cohesive parameters. 2. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 69–149. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sevil F, Bozkurt A. Proton conducting polymer electrolytes on the basis of poly(vinylphosphonic acid) and imidazole. J Phys Chem Solids. 2004;65:1659–62. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bingol B, Meyer WH, Wagner M, Wegner G. Synthesis, microstructure, and acidity of poly(vinylphosphonic acid) Macromol Rapid Comm. 2006;27:1719–24. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Komber H, Steinert V, Voit B. 1H, 13C and 31P NMR study on poly(vinylphosphonic acid) and its dimethylester. Macromolecules. 2008;41:2119–25. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Millaruelo M, Steinert V, Komber H, Klopsch R, Voit B. Synthesis of vinylphosphonic acid anhydride and their copolymerization with vinylphosphonic acid. Macromol Chem Phys. 2008;209:366–74. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tadic D, Peters F, Epple M. Continuous synthesis of amorphous carbonated apatites. Biomaterials. 2002;23:2553–9. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Starborg T, Lu Y, Huffman A, Holmes DF, Kadler KE. Electron microscope 3D reconstruction of branched collagen fibrils in vivo. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19:547–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shoulders MD, Raines RT. Collagen structure and stability. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:929–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.032207.120833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bozec L, van der Heijden G, Horton M. Collagen fibrils: nanoscale ropes. Biophys J. 2007;92:70–5. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.085704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahamid J, Sharir A, Addadi L, Weiner S. Amorphous calcium phosphate is a major component of the forming fin bones of zebrafish: indications for an amorphous precursor phase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12748–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803354105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silva GA. Neuroscience nanotechnology: progress, opportunities, and challenges. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:65–74. doi: 10.1038/nrn1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Endo A, Glimcher MJ. The effect of complexing phosphoproteins to decalcified collagen on in vitro calcification. Connect Tissue Res. 1989;21:179–96. doi: 10.3109/03008208909050008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saito T, Yamauchi M, Crenshaw MA. Apatite induction by insoluble dentin collagen. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:265–70. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li X, Chang J. Preparation of bone-like apatite-collagen nanocomposites by a biomimetic process with phosphorylated collagen. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;85:293–300. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Politi Y, Arad T, Klein E, Weiner S, Addadi L. Sea urchin spine calcite forms via a transient amorphous calcium carbonate phase. Science. 2004;306:1161–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1102289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim J, Arola DD, Gu L, Kim YK, Mai S, Pashley DH, et al. Functional biomimetic analogs help remineralize partially-demineralized resin-infiltrated dentin collagen matrices via a bottom-up approach. Acta Biomater. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.12.052. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dahl T, Sabsay B, Veis A. Type I collagen-phosphophoryn interactions: specificity of the monomer-monomer binding. J Struct Biol. 1998;123:162–8. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McMahon DJ, Oommen BS. Supramolecular structure of the casein micelle. J Dairy Sci. 2008;91:1709–21. doi: 10.3168/jds.2007-0819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jäger I, Fratzl P. Mineralized collagen fibrils: a mechanical model with a staggered arrangement of mineral particles. Biophys J. 2000;79:1737–46. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76426-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Balooch M, Habelitz S, Kinney JH, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW. Mechanical properties of mineralized collagen fibrils as influenced by demineralization. J Struct Biol. 2008;162:404–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yokoyama A, Gelinsky M, Kawasaki T, Kongo T, König U, Pompe W, et al. Biomimetic porous scaffolds with high elasticity made from mineralized collagen-an animal study. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2005;75:464–72. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cen L, Liu W, Cui L, Zhang W, Cao Y. Collagen tissue engineering: development of novel biomaterials and applications. Pediatr Res. 2008;63:492–6. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31816c5bc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang L, van der Werf KO, Fitié CF, Bennink ML, Dijkstra PJ, Feijen J. Mechanical properties of native and cross-linked type I collagen fibrils. Biophys J. 2008;94:2204–11. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.111013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boland T, Xu T, Damon B, Cui X. Application of inkjet printing to tissue engineering. Biotechnol J. 2006;1:910–7. doi: 10.1002/biot.200600081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sachlos E, Gotora D, Czernuszka JT. Collagen scaffolds reinforced with biomimetic composite nano-sized carbonate-substituted hydroxyapatite crystals and shaped by rapid prototyping to contain internal microchannels. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2479–87. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu CZ, Xia ZD, Han ZW, Hulley PA, Triffitt JT, Czernuszka JT. Novel 3D collagen scaffolds fabricated by indirect printing technique for tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2008;85B:519–28. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Deitch S, Kunkle C, Cui X, Boland T, Dean D. Collagen matrix alignment using inkjet printer technology. Mater Res Soc Symp Proc. 2008;1094:DD07–16. [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Jonge LT, Leeuwenburgh SC, van den Beucken JJ, te Riet J, Daamen WF, Wolke JG, et al. The osteogenic effect of electrosprayed nanoscale collagen/calcium phosphate coatings on titanium. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2461–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Daugaard H, Elmengaard B, Bechtold JE, Jensen T, Soballe K. The effect on bone growth enhancement of implant coatings with hydroxyapatite and collagen deposited electrochemically and by plasma spray. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;92:913–21. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]