Abstract

Poor vascularization coupled with mechanical instability is the leading cause of post-operative complications and poor functional prognosis of massive bone allografts. To address this limitation, we designed a novel continuous polymer coating system to provide sustained localized delivery of pharmacological agent, FTY720, a selective agonist for sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors, within massive tibial defects. In vitro drug release studies validated 64% loading efficiency with complete release of compound following 14 days. Mechanical evaluation following six weeks of healing suggested significant enhancement of mechanical stability in FTY720 treatment groups compared with unloaded controls. Furthermore, superior osseous integration across the host-graft interface, significant enhancement in smooth muscle cell investment, and reduction in leukocyte recruitment was evident in FTY720 treated groups compared with untreated groups. Using this approach, we can capitalize on the existing mechanical and biomaterial properties of devitalized bone, add a controllable delivery system while maintaining overall porous structure, and deliver a small molecule compound to constitutively target vascular remodeling, osseous remodeling, and minimize fibrous encapsulation within the allograft-host bone interface. Such results support continued evaluation of drug-eluting allografts as a viable strategy to improve functional outcome and long-term success of massive cortical allograft implants.

Introduction

Each year, nearly one million bone graft procedures are performed annually; including 800,000 bone allograft procedures in the United States alone [1,2]. However, 30%–60% of allograft implants exhibit complications by the 10-year mark. Particularly challenging is the incorporation of massive structural allografts that are commonly used for limb salvage, after tumor resection, and acute trauma. These allografts can provide vastly superior mechanical stability relative to morselized or demineralized allografts, but significant limitations in long-term functional capacity and poor host integration remain, including non-union fractures (10–30%), persistent infection (6–13%), and secondary fractures (10–30%) [3–5]. Notably, mode of fixation to enhance mechanical stability has no influence on rate of complications [6] and attempts to improve overall bone mass to protect against fatigue-induced fracture by local delivery of bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) have also failed to reduce long-term complications [7]. Interestingly, most cases presenting post-operative complications including non-union or fracture showed poor revascularization contiguous to the region of graft failure [8,9], and growing evidence suggests that the largest barrier to successful allograft incorporation and sustained mechanical integrity is not osseous remodeling but delayed or absent vascularization.

To address this limitation, our laboratory has been developing strategies to enhance neovascularization and promote osseous remodeling within massive osseous defect sites via sustained delivery of sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor targeted drugs. S1P is an autocrine and paracrine signaling small molecule that impacts proliferation, survival and migration of endothelial cells, mural cells (i.e. vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes), osteoblasts, and osteoblastic precursors through a family of high-affinity G protein-coupled receptors (S1P1–5) [10–14]. Selectively targeting a subset of S1P receptors with agonists and antagonist compounds (with longer bioactive half-lives than native S1P in vivo), one can control different biological responses. For example, recent reports suggest selective activation of S1P1 and S1P3 receptors via synthetic analog, FTY720, promote the recirculation of osteoclast precursor monocytes from the bone surface, an effect that ameliorates bone loss in models of postmenopausal osteoporosis [15]. Furthermore, FTY720 treatment demonstrates enhanced CXCR4-mediated migration of endothelial progenitor cells and homing of bone marrow progenitors in hindlimb ischemia models [16]. Recent discoveries of smooth muscle cell phenotype regulation in large arteries suggest possible synergies between S1P1 and S1P3, both targets of FTY720. Specifically, daily injections of S1P1/S1P3 antagonist (VPC44116) significantly decreased smooth muscle proliferation and migration [17]. Thus, FTY720 as a single bioactive factor has multiple cellular targets making it an attractive molecule for strategies to improve graft-host integration where multiple biological processes can be simultaneously augmented to address a central limitation, poor vascularization.

Previously, we have shown that sustained release of FTY720 from two dimensional biodegradable films (1:200 wt./wt.) of 50:50 poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLAGA) in the mouse dorsal skinfold window chamber promotes formation of new arterioles and structural enlargement of existing arterioles [18]. This pattern of FTY720-induced microvascular remodeling increases the number and diameter of microvessels, a therapeutic response that is critical for successful integration of allograft implants in vivo. In addition, implantation of 3D PLAGA scaffolds delivering FTY720 to critical size calvarial bone defects significantly increases osseous tissue ingrowth and the proportion of mature smooth muscle cell-invested microvessels within the bony defect [19]. In this study, we evaluate the ability of FTY720, locally released from thin biomaterial surfaces, to improve allograft vascularization, mechanical integrity, osseous remodeling, and ultimately incorporation at the host-graft interface. Specifically, we coated devitalized bone allografts with a thin polymer coating of FDA-approved 50:50 poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLAGA) encapsulated with bioactive FTY720. Subsequently, quantified drug loading and release kinetics in vitro, characterized changes in pore structure resulting from polymer coating, measured improvement in mechanical properties, and evaluated the biological remodeling near the defect in vivo. We also quantified the establishment of patent smooth muscle-invested vessels and examined the recruitment of leukocytes and deposition of bony tissue along the allograft-host bone interface.

Materials and Methods

Polymer Coating Solution

Polymer coatings using 50:50 or 85:15 poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLAGA, Mw = 72.3 kDa, Mw= 123.6 kDa respectively) were purchased from Lakeshore Biomaterials, Birmingham, AL. The polymer was dissolved in methylene chloride (MeCl) at three different wt./vol. ratios to achieve a range of coating viscosities (1:10, 1:12, 1:14). The solutions were agitated overnight to ensure homogeneity. For 50:50 PLAGA-coated, FTY720-loaded allografts (coated-loaded, C/L), 50:50 PLAGA was dissolved in MeCl at 1:12 (wt./vol.). FTY720 was then loaded into the polymer solution at 1:200 (wt./wt.). The solution containing polymer and drug was agitated briefly over heat until the drug dissolved completely. Samples were stored in a 4°C vacuum desiccator for at least 24 hours to remove residual solvent and preserve drug activity.

Bone Allograft Preparation

Samples of tibial and femoral bone were harvested from Sprague Dawley retired breeders. Both tibias and femurs had soft tissue cleaned off, distal ends bone removed, and bone marrow flushed from the cavity. Remaining segments were agitated in a chloroform solution overnight to remove any residual fatty tissue. Following a brief 70% ethanol rinse, the allograft tissue was autoclaved for sterilization (121°C at 15 PSI for 20 min) and allowed to fully dry. For polymer characterization studies, allograft samples were cut to 10 mm in length. For in vivo tibial defect studies, allograft samples were cut to 8 mm in length. Samples were stored in a −20°C freezer until use. To coat allograft samples, the specified polymer solution was drawn up into the syringe containing the bone held in place; this allowed the solution to pass over and through the stationary sample. The solution was then expelled and this pumping motion continued for a total coating time of 10 min. Following coating, samples were stored in a −20°C freezer for 72 hours to allow the slow evaporation of solvent.

Encapsulation Efficiency and Sphingolipid Release

Allograft samples were coated similarly to the above protocol with radio-labeled sphingosphine 1-phosphate (S1P, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor MI) to measure drug release over a 14-day period. Specifically, 2.92 mg of S1P was resolubilized in MeCl to a final concentration of 2 mg/mL by frequent heating and vortexing. Using a conversion factor of 2.2×106 cpm/μCi and 1 μCi/μL, 6.8 μL of Phosphorus-33 (33P) (Perkin Elmer, Inc., Waltham, MA) was added to the S1P solution. Next, 583 mg of 50:50 PLAGA was added to the S1P-33P solution to achieve a 1:12 (wt./vol.) polymer-solvent ratio. The final solution had 2.92 mg of S1P, 6.8 μL of 33P, and 583 mg of 50:50 PLAGA mixed in 7 mL of MeCl. The allografts were then placed into a glass scintillation vial containing 50 μL of simulated body fluid (SBF) with 4% fatty acid free (FAF) BSA. Following 24 hours incubation, the allografts were removed from the vials and the remaining 4% FAF-BSA SBF was mixed with 5 mL of EcoScintA biodegradable scintillation solution for quantifying drug release using the Beckman Coulter liquid scintillation counter. Allografts were then placed into a new glass vial containing fresh 4% FAF-BSA SBF. This cycle was repeated for a 14-day period to achieve cumulative measurements. Encapsulation efficiency (maximum amount of S1P that can be released) was quantified by placing allografts in MeCl to completely dissolve the drug-containing polymer solution.

Critically-sized Tibial Defect Model

All animal surgeries were performed according to an approved protocol from the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee. Briefly, adult male Sprague Dawley rats (~400 g) were randomly assigned to three different experimental groups: uncoated allograft (U), coated 1:12 PLAGA (C), and coated 1:12 PLAGA loaded with 1:200 FTY720 (C/L). Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane gas. Following anesthetization, the dorsal skin was sterilized with betadine and 70% ethanol. A small incision was made longitudinally over the midshaft of the tibia. Subperiosteal dissection was performed once the subcutaneous tissue was dissected over the anterior aspect of the tibia. A Dremel rotary tool with a Diamond Wheel accessory was used to make an 8 mm defect slightly distal to the tibial tubercle and the 8 mm allograft segment was inserted into the defect. A stab incision was made just medial to the patellar tendon and a 19.5 gauge needle was inserted into the intramedullary canal, through the allograft, into the distal intramedullary canal to resistance, and tamped flush to the bone. The incision was irrigated and closed with 4-0 Nylon suture. Following closure, Buprenorphine was administered intramuscularly (0.1 mg/kg) after surgery and then as needed to minimize pain post surgery. Only the left tibia per animal was used, leaving the right side for normal function.

MicroCT Imaging (Polymer Coating Characterization, In Vivo, Ex Vivo)

To characterize polymer coating thickness and changes in allograft pore structure, samples were imaged using the quantitative micro-computed tomography (microCT) scanner (Scanco, Bassersdorf, Switzerland). Allograft samples from each group (PLAGA 1:10, PLAGA 1:12, PLAGA 1:14) were imaged utilizing a high-resolution 45 kVp scan. Following reconstruction of the 2D slices, an appropriate threshold matching the original grayscale image was chosen, contour lines were drawn around the allograft, and 3D images were generated. Total volume of bone and polymer, average pore size, and thickness of the polymer coating on the outer surface and inner canal of the bone were measured utilizing the 3D evaluation software. Subsequently, the polymer-coated allografts were agitated in MeCl overnight to dissolve the polymer coating and generate the uncoated bone sample. The samples were re-imaged and analyzed using microCT to measure the bone volume only and the average pore size of the uncoated bone. Bone volume of the uncoated allograft was subtracted from total bone and polymer volume of the coated allograft to obtain a measure of polymer volume. Average pore size of the uncoated allograft was subtracted from the average pore size of the coated allograft to obtain a measure of the change in pore size after coating; the resulting number was negative if the average pore size decreased after coating. The thresholds (bone: lower = 200, upper = 1000; polymer: lower = 112, upper = 200; bone + polymer: lower = 112, upper = 1000) and scan parameters (bone: support = 4, width = 1.2; polymer: support = 6, width = 3.4; bone + polymer: support = 6, width = 1.2) were kept constant throughout the entire study.

New bone healing along the length of the allograft insertion site was imaged post-operatively at 0, 2, 4, and 6 weeks. Animals were anesthetized by isofluorane gas and imaged for 11.7 minutes utilizing a low-resolution 45 kVp scan. At end time points, animals were euthanized, the hindlimb was disarticulated, the soft tissue was stripped, and the intramedullary pin was removed. Ex vivo scans of each specimen were obtained utilizing a high-resolution 45 kVp scan. Following reconstruction of the 2D slices, an appropriate threshold matching the original grayscale images was chosen. Contour lines were drawn to appropriately select a standard window of 2 mm × 0.15 mm drawn 0.4 mm away from the interface between the host bone and allograft. These standard contour lines were drawn around both the host bone and allograft but excluded the hollow canal. 3D images were created from 2D slices, and the bone density within the contour lines was calculated using the 3D evaluation program. The standard window, threshold (260 for high resolution ex vivo bone volume data, 200 for low resolution in vivo qualitative 3D images), and scan parameters (support = 4, width = 1.2) were kept constant throughout the entire study.

Evaluation of Post-operative Mechanical Properties

Excised tibias were tested under compression in an Instron 4511 machine to determine the elastic modulus and ultimate compressive strength (UCS) of uncoated, coated, and coated/loaded (50:50 PLAGA + 1:200 FTY720) allograft samples. The tibial portion of the limb was harvested from knee to ankle and stored at 4°C no longer than 24 hours before testing. The primary goal was to determine the strength of the integrated structure (host-bone-allograft) 6 weeks post-op. All compression testing was performed at a rate of 1 mm/min until sample failure.

Evaluation of Post-operative Tissue Histology

Following ex vivo microCT scanning at 6 weeks, tibia samples were fixed in 10% formalin, decalcified using Richard Scientific Decalcifying Solution (Kalamazoo, MI) for 2 days at room temperature, and dehydrated overnight. Half the samples were embedded in paraffin and the other half cryo-sectioned. Each sample was cut along the sagittal plane at the midline of the defect. For smooth muscle α-actin (SMA) staining to visualize mature vessel lumens, four 7 μm-thick histological sections per sample (paraffin-embedded) were dewaxed, rehydrated, blocked 3 × 10 minutes in PBS/saponin/BSA and immunolabeled for SMA using CY3-conjugated monoclonal anti-SMA (Sigma Aldrich) diluted 1:200 in PBS/saponin/BSA. Slides were incubated with antibodies for approximately 15 hours at 4°C. Subsequently, tissues were washed 3 times in PBS/saponin for 10 min each. Samples were then mounted using a 50:50 solution of PBS and glycerol. For CD45 staining to visualize leukocyte recruitment, four 7 μm-thick histological sections per sample (cryo-embedded) were blocked 3 × 10 minutes in PBS/saponin/BSA and immunolabeled with CD45 (BD Pharmingen) diluted 1:50 in PBS/saponin/BSA. Slides were incubated with antibodies for approximately 15 hours at 4°C followed by the secondary antibody streptavidin 488 for additional 15 hours at 4°C. Subsequently, tissues were washed 3 times in PBS/saponin for 10 min each. Samples were then mounted using a 50:50 solution of PBS and glycerol. For hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson's Trichrome staining to visualize collagen fiber morphology, four 7 μm-thick histological sections per sample (paraffin-embedded) were dewaxed, rehydrated, and appropriately stained. Immunostained sections were imaged using both a Nikon TE 2000-E2 confocal microscope and Zeiss Axioskop 40 inverted microscope. Representative images were acquired using 4×, 10×, and 50× objectives. To quantify changes in vascular remodeling (particularly recruitment of mural cells) in response to FTY720, SMA-positive cells that formed an obvious lumen were quantified in each tissue section. Total tissue area was measured in ImageJ, and the FTY720-mediated response was represented as a fraction of SMA-positive lumens per total tissue area.

Statistical significance

Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis of polymer coating thickness, bone density, mechanical properties, and vessel density was performed using a one-way General Linear ANOVA, followed by Tukey's test for pairwise comparisons. Significance was asserted at p < 0.05.

Results

Polymer-Coated Allograft Characterization

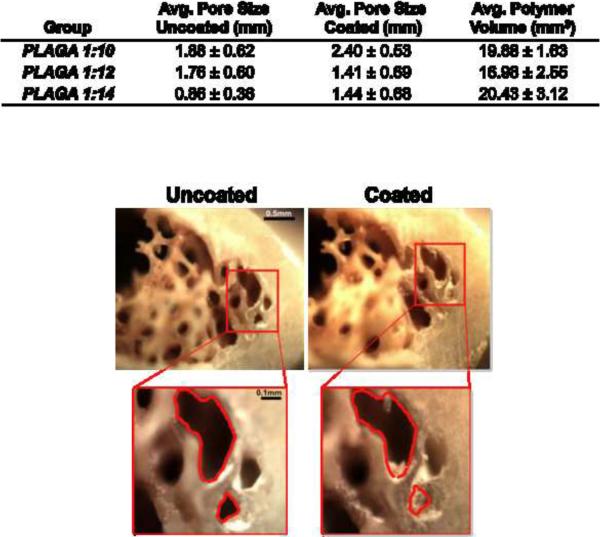

Changes in average pore size between coated and uncoated samples were measured by microCT imaging analysis. Allografts were scanned before and after coating with each PLAGA concentration (1:10, 1:12, 1:14) (Fig 1A). The 1:12 concentration was chosen to provide an even pore coating while maintaining the general pore structure important for osteoconductivity and fracture healing. As expected, data trends showed average pore size decreases following polymer coating. Despite decreases in average pore size, macroscopic cross-sections of tibial bone revealed preservation of many larger pore features following polymer coating (Fig 1B). These images suggested that although average pore size was reduced in most groups following coating, the overall pore structure was maintained; this property is critical for osteoconductivity and fracture healing. Furthermore, the total volume of polymer implanted at the defect site was less than 5% of the allograft itself, thus keeping degradation byproducts to a minimum. The thickness of polymer coating on both inner and outer surfaces was also measured by microCT imaging. Thicknesses ranged from 0.1 mm to 0.2 mm, where smooth outer surfaces retained thinner layers of polymer compared with porous inner surfaces (Fig 2A). Measurements of thicknesses were similar across polymer types and solution ratios. Representative images from each group display polymer coating in red, bone tissue in white, and marrow cavity in black (Fig 2B).

Fig 1. Characterization of PLAGA-coated allograft pore size.

(A) Outline of parameters used to create various PLAGA coatings, where average pore size before and after coating and total volume of PLAGA coating is calculated for each sample using microCT evaluation. (B) Macroscale images of allograft cross-sections with representative polymer coating. Images show complete obstruction of smaller pores by polymer coating, whereas larger pores retain open structure.

Fig 2. Characterization of PLAGA coating thickness.

(A) Thickness of the PLAGA coating on the outer surface and the inner canal of the allograft, measured for each experimental group using microCT evaluation. n = 4 per group. (B) Cross-sectional slice of rat femur allograft coated with PLAGA. Threshold values show bone tissue in white (200–1000) and PLAGA coating in red (112–200). Scale bar = 1 mm.

Encapsulation Efficiency and Drug Release

To determine total amount of drug loaded into allograft implants and the kinetics of drug release, in vitro experiments were conducted utilizing allografts loaded with S1P-33P (Fig 3). Complete degradation of PLAGA occurs between 6–8 weeks [20]. However, substantial S1P release was expected to occur earlier, given the bulk degradation profile of PLAGA. We found approximately 0.64 mg of the original 1 mg of S1P was actually loaded within the polymer-coated allograft (64% loading efficiency). After 14 days incubation, 0.57 mg of S1P was detected in the simulated body fluid (SBF). This amount was assumed to be the total amount of S1P loaded given the minimal increases in S1P release at later time points. An initial burst release of drug was observed during the first five days, typical for 50:50 PLAGA degradation profiles.

Fig 3. Characterization of polymer degradation and drug release.

In vitro percent release of S1P from PLAGA-coated allografts was measured using radioactive 33P labeling. Approximately 0.57 mg of S1P was released in 14 days with a loading efficiency of 64%. Since S1P and FTY720 have similar molecular weights and structures, we assume FTY720 exhibits similar release profiles from coated allografts.

In Vivo MicroCT Analysis

Bone healing was monitored at 2, 4, 6 weeks post surgery utilizing low-resolution in vivo microCT imaging. At six-week endpoints, samples were scanned ex vivo at high resolution (Fig 4A) and quantitative values of bone density near the host bone-allograft interface were calculated for each sample from the high resolution ex vivo scans (Fig 4B). Qualitative images suggest better integration of remodeled bone along the length of the implanted allograft in the coated-loaded (C/L) group compared with unloaded (U) and coated (C) groups. This qualitative analysis suggests a positive effect of FTY720 on the spatial distribution and integration of new bone at the implant-tibial interface. Additionally, bone density measurements were calculated for high resolution ex vivo scans for all groups. Comparisons between bone density in host tissue and allograft regions suggest a closer match of densities within the C/L group compared with U and C groups. Thus, FTY720 treatment may promote osseous tissue remodeling such that allograft/bone density interface is well-matched to promote long-term allograft incorporation.

Fig 4. MicroCT imaging of bone remodeling.

(A) Representative images show in vivo microCT low resolution scans of segmental defects at the day of the surgery and following 6 weeks healing. Defects loaded with either uncoated allografts (U), 1:12 PLAGA coated allografts (C), or 1:12 PLAGA coated, 1:200 FTY720 loaded allografts (C/L). C/L group shows superior osseous integration particularly at the interface of the defects. Scale bar = 1 mm. (B) Bone density of the host bone and allograft near the interface was calculated using microCT evaluation. The density of the C/L allograft is closest to the density of the host bone compared to the U and C groups, perhaps due to active remodeling of the bone in this group.

Mechanical Testing

A leading cause of allograft failure or post-operative complications includes mechanical instability at the bone-allograft interface. Thus, mechanical testing following six-weeks healing was performed using an Instron machine to determine the elastic modulus of all groups (U, C, C/L) ex vivo (Fig 5A). To determine the elastic modulus, the slope was calculated between the values of 0.07 to 0.08 strain, since this was the interval in which the elastic region existed in all the graphs. Both values of elastic modulus and ultimate compressive strength (Fig 5B) were significantly higher in C/L groups compared with both U and C groups. Superior mechanical properties in C/L groups supported qualitative microCT images and quantitative bone density measurements, suggesting that local FTY720 delivery may effectively increase the structural integrity of the allograft-host bone interface.

Fig 5. Measurement of elastic modulus and ultimate compressive strength.

(A) Results from the Instron 4511 demonstrate that the 1:12 PLAGA coated + 1:200 FTY720-loaded (C/L) group had a significantly higher elastic modulus in comparison to the U and C groups. *Statistically significant compared with U and C (where p < 0.05). (B) *Statistically significant compared with U and C (where p = 0.081).

Immunofluorescence Analysis

Previous observations demonstrated significant increases in smooth muscle cells investment when FTY720 was delivered locally in both cranial defect and dorsal skinfold window chamber models [18,19]. In massive allograft implants, poor vascularization is a leading cause for post-operative complications and failure of massive bone allografts. To this end, FTY720 was locally delivered to encourage vascularization of the interface region and subsequently smooth muscle cell was quantified. Similar to previous applications, FTY720 treatment significantly increased the number of SMCs within the interface regions compared with C and U groups (Fig 6A). Immunostaining showed continuous lumens with signature “tire-track” alpha-smooth muscle actin staining within allograft regions (Fig 6B). In additional to enhancing bone and vascular remodeling, FTY720 treatment in vivo has also demonstrated immunosuppressive properties. Here, using a pan-leukocyte stain, qualitative images suggested reductions in the number of hematopoietic lineage leukocytes within the allograft-host bone interface when treated with FTY720 (Fig 6C).

Fig 6. Assessment of mural cell and leukocyte recruitment.

(A) Number of blood vessels stained with smooth muscle a-actin. aStatistically significant between C/L and both U and C groups (where p < 0.05). (B) Representative confocal microscopic images of SMA+ mural cells (red) within tissue sections from uncoated, (U) 1:12 PLAGA-coated (C), and 1:12 PLAGA-coated, 1:200 FTY720-loaded (C/L) allografts. (C) Representative confocal microscopic images of CD45+ leukocytes (green) within tissue sections from uncoated, (U) 1:12 PLAGA-coated (C), and 1:12 PLAGA-coated, 1:200 FTY720-loaded (C/L) allografts. Scale bar = 150 mm.

Bone remodeling and collagen fibril alignment were visualized through H&E and Masson's trichrome staining of longitudinal cross-sections of allograft-host bone interfaces. FTY720 treated groups (Fig 7C) showed superior collagen alignment, osseous tissue generation along the outer edge of the allograft tissue, better preservation of inner cancellous porous regions, and preservation of allograft-tibial alignment compared with U (Fig 7A) and C (Fig 7B) groups.

Fig 7. H&E and Masson's trichrome staining of tibial defects.

(A) Uncoated (U) and (B) 1:12 PLAGA-coated (C) samples show poor allograft-host bone integration after 6 weeks healing while (C) 1:200 FTY720-loaded (C/L) group show superior osseous integration with newly-formed bony islands. Substantial osteogenesis observed in the FTY720-loaded group (C/L). Scale bar = 250 mm.

Discussion

Poor vascularization and hampered osseous graft integration are commonly associated with long-term complication and poor functional outcome of massive skeletal allografts [3–5,8,9]. Promising new strategies designed to directly address limitations in vascularization of allograft regions include co-delivery of stem cells [21], platelet-rich plasma [22], recombinant proteins [23], and gene therapy [24]. In particular, recent clinical data suggests that rhBMP2 proteins can be effective in improving repair success in non-union fracture healing and cervical spine fusion; however, concerns persist regarding the delivery of large amounts of rhBMP2 and associated complications, including edema and ectopic bone formation [25,26]. Moreover, adjunct therapies focused exclusively on enhancement of overall bone mass to aid graft incorporation have failed to significantly reduce these post-operative complications [7]. Our laboratory is interested in developing and evaluating alternative approaches utilizing small molecule compounds, including pharmacological agonists and antagonists of S1P receptors.

In this study, we have coated devitalized tibial grafts with a thin layer of PLAGA to support the controlled delivery of FTY720 to the host-graft interface, while successfully maintaining overall porous structure of cancellous bone. Utilizing biodegradable polymer systems is an effective strategy to incorporate sustained drug release in vivo. Previous factor-eluting polymer coating systems have utilized titanium implants coated with poly(D,L-lactide) to locally deliver TGF-beta-1 and IGF-1 [27]. In these studies, enhanced mechanical fixation and osseointegration were observed at the host-graft interface and minimal fibrous scarring was noted. Others have evaluated the effectiveness of coating cortical bone with poly(propylene fumarate) foam to enhance allograft incorporation [27–29]. In these studies, strength to failure of the coated allograft groups was stronger at the interface compared with uncoated grafts. Additionally, authors suggested that polymer-coated grafts were better protected from excessive osteoclastic resorption, a process that can often enhance fibrous scar invasion and ultimately deteriorate effective allograft incorporation. To this end, we developed a novel polymer coating system, where a continuous polymer layer is coated across the entire porous allograft surface, creating a sustainable localized delivery mechanism within a massive tibial defect site. Using this approach, we can capitalize on the existing properties of devitalized bone and provide a barrier from excessive osteoclastic resorption. Moreover, local administration of FTY720 allows us to exploit the multiple biological functions of the S1P receptor signaling axis to promote bone healing.

Fundamentally, we understand that following injury, local vasculature and damaged osseous tissue incite an inflammatory response that proceeds via complement activation, recruitment of monocytes/macrophages, and eventual clearance of damaged tissues. Additionally, timely integration of functional vascular networks is critical to initiate appropriate osseous remodeling, similar to the microvessels in developing embryos which serve as a bed for osteoblastic development and differentiation [30,31]. Given the emerging evidence elucidating downstream effects of selective S1P1/S1P3 activation on microvascular development and stabilization, we believe that the delivery of FTY720 may be effective for inducing growth and development of mature microvascular networks within allograft regions, leading to improved bone healing outcomes and reducing post-op complications. Specifically, our results show that local delivery of FTY720 led to two significant outcomes. First, it enhanced the number of smooth-muscle-invested vessels within allograft tissue sections, a hallmark of mature microvessel network growth. Second, it promoted significant new bone formation with statistically significant increases in compressive modulus and ultimate tensile strength after only 6 weeks implantation.

These results are consistent with the wealth of evidence supporting the critical role of S1P receptors in vascular development and signaling in both vascular endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells. Global knockout of S1P1 is embryonic lethal through hemorrhaging as a result of aberrant recruitment of smooth muscle cells to nascent endothelial tubes [32]. Tissue-specific knockout of S1P1 in endothelial cells phenocopies the global S1P−/− knockout phenotype, likely due to disruption of N-cadherin-dependent adhesive contacts between endothelial cells and mural cells that are critical to vascular maturation in the embryo [33]. Moreover, in vitro and in vivo studies of mature SMCs show that S1P1 and S1P3 promote the proliferation and migration of SMCs, which are critical to vascular network maturation [17]. These results support the idea that pharmacological targeting of S1P1/S1P3 with drugs like FTY720 is an exciting new approach to therapeutic neovascularization and enhancement of bone healing.

Modulation of local immune response and foreign body reaction may also be part of the mechanism by which FTY720 promotes allograft incorporation. Clinically, systemic delivery of FTY720 has shown potent immunomodulatory effects, preventing lymphocyte egress and recirculation from the thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs [34]. Moreover, S1P1 antagonizes pathologic inflammation by preventing monocyte adhesion to activated endothelium [35], and recent evidence has shown that treatment with FTY720 ameliorates osteoporosis in mice by reducing the osteoclast population size [15]. In our study, we observed significant reduction in the number of CD45+ leukocytes near graft sections. This result was consistent with previous studies from our group showing dramatic reduction in CD45+ cell recruitment in response to localized FTY720 release in both dorsal skinfold window chamber studies (data not shown) and cranial bone defects studies [18,19]. As part of the innate immune response, fibrous tissue may often invade and surround bone implants, creating a discontinuous strain interface that is mechanically inferior to cortical bone. Moreover, the formation of fibrous tissue is a significant barrier to microvascularization and osseous tissue ingrowth. Thus, delivery of FTY720 may act locally to reduce the formation of fibrous tissue invasion of allograft implants by reducing leukocyte trafficking near graft regions.

Because such strong coordination exists between inflammatory cell recruitment and wound healing progression towards resolution, inflammation-driven modulation of S1P receptor signaling may also play an important role in recruitment of marrow derived mesenchymal progenitor cells to sites of tissue regeneration. For example, recent data indicate that the therapeutic success of transplanted progenitor or stem cells can be improved by pharmacological stimulation of surface receptors in order to enhance homing to sites of injury and ischemia. Indeed, several studies have explored the dynamics of SDF-1α/CXCR4 cross talk with S1P receptor signaling and its possible role in directing MPC adhesion and recruitment. Activation of S1P1 and S1P3 by FTY720 augments SDF-1-dependent transendothelial progenitor cell migration in vitro and bone marrow homing [36]. These observations support previous data from our laboratory suggesting that local delivery of FTY720 to cranial defects may enhance bone ingrowth through recruitment of local bone progenitor cells from the meningeal dura mater and adjacent soft tissues [19].

Conclusions

Allograft products continue to be an attractive option for replacement strategies in massive skeletal defects including spinal fusion and joint revision. However, devitalized grafts must be quickly re-populated and vascularized in vivo for proper long-term functional success. Here, we have successfully coated grafts with a thin layer of PLAGA, successfully maintained overall porous structure of cancellous bone, locally delivered FTY720 to the host-graft interface, enhanced mechanical stability and vascular recruitment, appropriately remodeled osseous tissue surrounding the interface, and reduced leukocyte trafficking near the implant site. Such results support continued evaluation of drug-eluting allografts as a viable strategy to improve functional outcome and long-term success of massive cortical allograft implants.

Acknowledgements

Sources of support for this study include the UVA Coulter Translational Research Partnership Program and National Institutes of Health grants K01AR052352-01A1, R01AR056445-01A2, R01DE019935-01 to Dr. Botchwey. Dr. Caren Petrie Aronin is supported by the Biotechnology Training Program grant T32 GM-008715-03. Dr. Lauren Sefcik is supported by predoctoral fellowships from the National Science Foundation and American Heart Association Mid-Atlantic Affiliate 0815211E. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Trey Cui for funding support of Drs. Jones-Quaidoo, Zawodny and Bagayoko.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Giannoudis PV, Dinopoulos H, Tsiridis E. Bone substitutes: an update. Injury. 2005;36(Suppl 3):S20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenwald AS, Boden SD, Goldberg VM, Khan Y, Laurencin CT, Rosier RN, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The Committee on Biological Implants Bone-graft substitutes: facts, fictions, and applications. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(Suppl 2 Pt 2):98–103. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200100022-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wheeler DL, Enneking WF. Allograft bone decreases in strength in vivo over time. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;435:36–42. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000165850.58583.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delloye C, de Nayer P, Allington N, Munting E, Coutelier L, Vincent A. Massive bone allografts in large skeletal defects after tumor surgery: a clinical and microradiographic evaluation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1988;107:31–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00463522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mankin HJ, Hornicek FJ, Raskin KA. Infection in massive bone allografts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;432:210–216. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000150371.77314.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vander Griend RA. The effect of internal fixation on the healing of large allografts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:657–663. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199405000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boraiah S, Paul O, Hawkes D, Wickham M, Lorich DG. Complications of recombinant human BMP-2 for treating complex tibial plateau fractures: a preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:3257–3262. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1039-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delloye C, Cornu O, Druez V, Barbier O. Bone allografts: What they can offer and what they cannot. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:574–579. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B5.19039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson RC, Jr, Pickvance EA, Garry D. Fractures in large-segment allografts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1663–1673. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199311000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Desai NN, Olivera A, Seki T, Brooker G, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate, a novel lipid, involved in cellular proliferation. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:155–167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuvillier O, Pirianov G, Kleuser B, Vanek PG, Coso OA, Gutkind S, et al. Suppression of ceramide-mediated programmed cell death by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Nature. 1996;381:800–803. doi: 10.1038/381800a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee MJ, Thangada S, Paik JH, Sapkota GP, Ancellin N, Chae SS, et al. Akt-mediated phosphorylation of the G protein-coupled receptor EDG-1 is required for endothelial cell chemotaxis. Mol Cell. 2001;8:693–704. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryu J, Kim HJ, Chang EJ, Huang H, Banno Y, Kim HH. Sphingosine 1-phosphate as a regulator of osteoclast differentiation and osteoclast-osteoblast coupling. EMBO J. 2006;25:5840–5851. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pebay A, Bonder CS, Pitson Stem cell regulation by lysophospholipids. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;84:83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishii M, Egen JG, Klauschen F, Meier-Schellersheim M, Saeki Y, Vacher J, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate mobilizes osteoclast precursors and regulates bone homeostasis. Nature. 2009;458:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature07713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walter DH, Rochwalsky U, Reinhold J, Seeger F, Aicher A, Urbich C, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate stimulates the functional capacity of progenitor cells by activation of the CXCR4-dependent signaling pathway via the S1P3 receptor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:275–282. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000254669.12675.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wamhoff BR, Lynch KR, Macdonald TL, Owens GK. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor subtypes differentially regulate smooth muscle cell phenotype. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1454–1461. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sefcik LS, Petrie Aronin CE, Wieghaus KA, Botchwey EA. Sustained release of sphingosine 1-phosphate for therapeutic arteriogenesis and bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2869–2877. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrie Aronin C, Sefcik LS, Tholpady A, Sadik KW, Tholpady SS, Macdonald TL, et al. FTY720 promotes local microvascular network formation and regeneration of cranial bone defects. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010 Mar 8; doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0539. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramchandani M, Pankaskie M, Robinson D. The influence of manufacturing procedure on the degradation of poly(lactide-co-glycolide) 85:15 and 50:50 implants. J Control Release. 1997;43:161–173. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucarelli E, Fini M, Beccheroni A, Giavaresi G, Di Bella C, Aldini NN, et al. Stromal stem cells and platelet-rich plasma improve bone allograft integration. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;435:62–68. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000165736.87628.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han B, Woodell-May J, Ponticiello M, Yang Z, Nimni M. The effect of thrombin activation of platelet-rich plasma on demineralized bone matrix osteoinductivity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1459–1470. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nevins M, Hanratty J, Lynch SE. Clinical results using recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor and mineralized freeze-dried bone allograft in periodontal defects. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2007;27:421–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yazici C, Yanoso L, Xie C, Reynolds DG, Samulski RJ, Samulski J, et al. The effect of surface demineralization of cortical bone allograft on the properties of recombinant adeno-associated virus coatings. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3882–3887. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cahill KS, Chi JH, Day A, Claus EB. Prevalence, complications, and hospital charges associated with use of bone-morphogenetic proteins in spinal fusion procedures. JAMA. 2009;302:8–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shields LB, Raque GH, Glassman SD, Campbell M, Vitaz T, Harpring J, et al. Adverse effects associated with high-dose recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 use in anterior cervical spine fusion. Spine. 2006;31:542–547. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000201424.27509.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamberg A, Schmidmaier G, Soballe K, Elmengaard B. Locally delivered TGF-beta1 and IGF-1 enhance the fixation of titanium implants: a study in dogs. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:799–805. doi: 10.1080/17453670610013024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewandrowski KU, Bondre S, Hile DD, Thompson BM, Wise DL, Tomford WW, et al. Porous poly(propylene fumarate) foam coating of orthotopic cortical bone grafts for improved osteoconduction. Tissue Eng. 2002;8:1017–1027. doi: 10.1089/107632702320934119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bondre S, Lewandrowski KU, Hasirci V, Cattaneo MV, Gresser JD, Wise DL, et al. Biodegradable foam coating of cortical allografts. Tissue Eng. 2000;6:217–227. doi: 10.1089/10763270050044399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Streeten EA, Brandi ML. Biology of bone endothelial cells. Bone Miner. 1990;10:85–94. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(90)90084-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drushel RF, Pechak DG, Caplan AI. The anatomy, ultrastructure and fluid dynamics of the developing vasculature of the embryonic chick wing bud. Cell Differ. 1985;16:13–28. doi: 10.1016/0045-6039(85)90603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Wada R, Yamashita T, Mi Y, Deng CX, Hobson JP, et al. Edg-1, the G protein-coupled receptor for sphingosine-1-phosphate, is essential for vascular maturation. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:951–961. doi: 10.1172/JCI10905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paik JH, Skoura A, Chae SS, Cowan AE, Han DK, Proia RL, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor regulation of N-cadherin mediates vascular stabilization. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2392–2403. doi: 10.1101/gad.1227804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cinamon G, Lesneski MJ, Xu Y, Brinkmann V, et al. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 2004;427:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whetzel AM, Bolick DT, Srinivasan S, Macdonald TL, Morris MA, Ley K, et al. Sphingosine-1 phosphate prevents monocyte/endothelial interactions in type 1 diabetic NOD mice through activation of the S1P1 receptor. Circ Res. 2006;99:731–739. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000244088.33375.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimura T, Boehmler AM, Seitz G, Kuci S, Wiesner T, Brinkmann V, et al. The sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor agonist FTY720 supports CXCR4-dependent migration and bone marrow homing of human CD34+ progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;103:4478–4486. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]