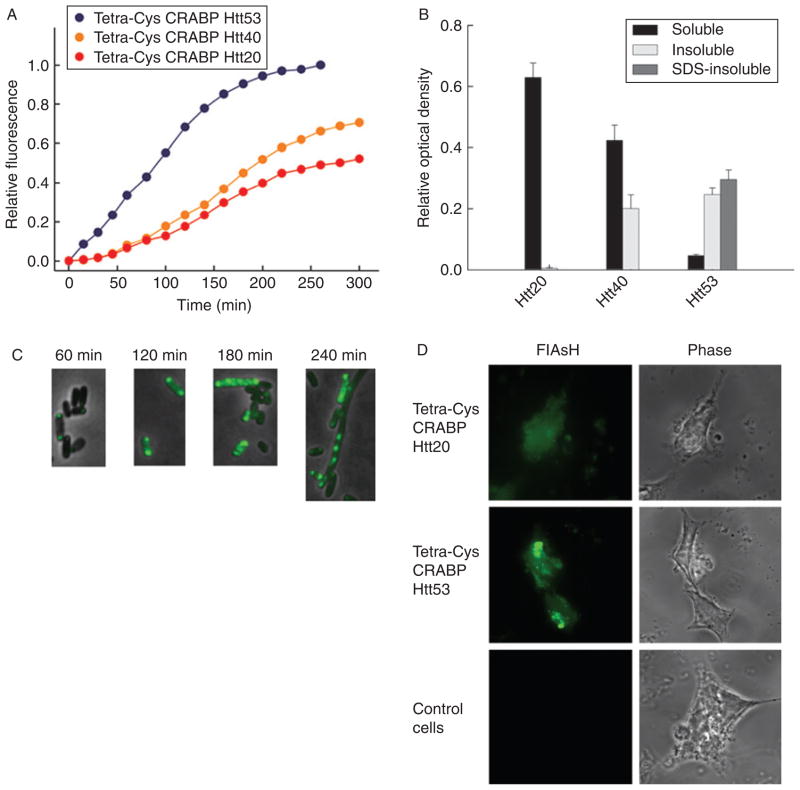

Fig. 3.

Chimeras of tetra-Cys CRABP and the exon 1-encoded portion of Htt show polyQ-length-dependent aggregation. (A) Time course of bulk fluorescence (at 530 nm; excitation 500 nm) of FlAsH-labeled E. coli cells expressing tetra-Cys CRABP Htt20 (red), Htt40 (orange), and Htt53 (blue). (B) Partitioning of the chimeras between the soluble (black bars), detergent-labile insoluble (light gray bars), and SDS-resistant insoluble (dark gray bars) cytoplasmic fractions at the conclusion of the experiment shown in Fig. 2A (260 min after induction of the protein synthesis). (C) Tetra-Cys CRABP Htt53 chimera forms hyperfluorescent aggregates in the E. coli host, and the appearance of the SDS-resistant species coincides with the appearance of the filamentous phenotype of the E. coli cells. (D) Fluorescence microscopic images of FlAsH-labeled eukaryotic HEK293T cells transiently transfected with tetra-Cys CRABP Htt chimeras. Tetra-Cys CRABP Htt20 is soluble and yields uniformly distributed FlAsH fluorescence, whereas tetra-Cys CRABP Htt53 generates hyperfluorescent loci. Cells transfected with empty pcDNA3.1 vector serve as control. The localization of the tetra-Cys CRABP Htt chimeras is visualized as indicated (by FlAsH fluorescence or phase contrast). Parts of this figure are reproduced from Ignatova and Gierasch (2006).