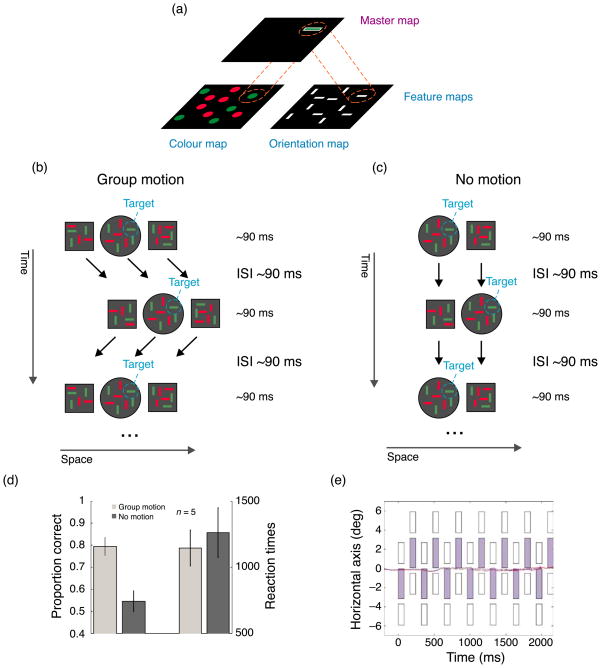

Figure 5.

Ternus search. (a) Feature integration theory. Features are coded in retinotopic feature maps, one map for each basic feature dimension. To bind features together, a master map operates on the feature maps. If, for example, a green, horizontal line has to be searched for, the master map “checks” whether there is a “green” entry in the color map and a “horizontal” entry in the orientation map at the same retinotopic location in each map. (b) On each square and the central disk, a different search display was presented. The squares and the disk were shifted by one inter-element spacing back and forth. Five observers searched for a green, horizontal line in the central disk. Because of group motion and the corresponding non-retinotopic integration, search is quite accurate in the group motion condition (see (d)). (c) When the outer squares are omitted, group motion is obliterated and “integration” is retinotopic. This creates strong masking effects because different search displays alternate at each retinotopic location. (d) Results. Accuracy is higher and reaction times are faster for the group motion condition compared to the no motion condition. (e) There are virtually no (horizontal) eye movements during visual search when group motion is perceived. Data from one naive observer (the data from the other observer, author MB, are very similar). The stimulus layout is plotted as in Figure 3e.