Abstract

Rationale and Objectives

To conduct a pre-clinical evaluation of the robustness of our computerized system for breast lesion characterization on two breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) databases that were acquired using scanners from two different manufacturers.

Materials and Methods

Two clinical breast MRI databases were acquired from a Siemens scanner and a GE scanner, which shared similar imaging protocols and retrospectively collected under an IRB-approved protocol. In our computerized analysis system, once a breast lesion is identified by the radiologist, the computer performs automatic lesion segmentation and feature extraction, and outputs an estimated probability of malignancy. We used a Bayesian neural network with automatic relevance determination for joint feature selection and classification. To evaluate the robustness of our classification system, we first used Database 1 for feature selection and classifier training, and Database 2 to test the trained classifier. Then, we exchanged the two datasets and repeated the process. Area under the ROC curve (AUC) was used as a performance figure of merit in the task of distinguishing between malignant and benign lesions.

Results

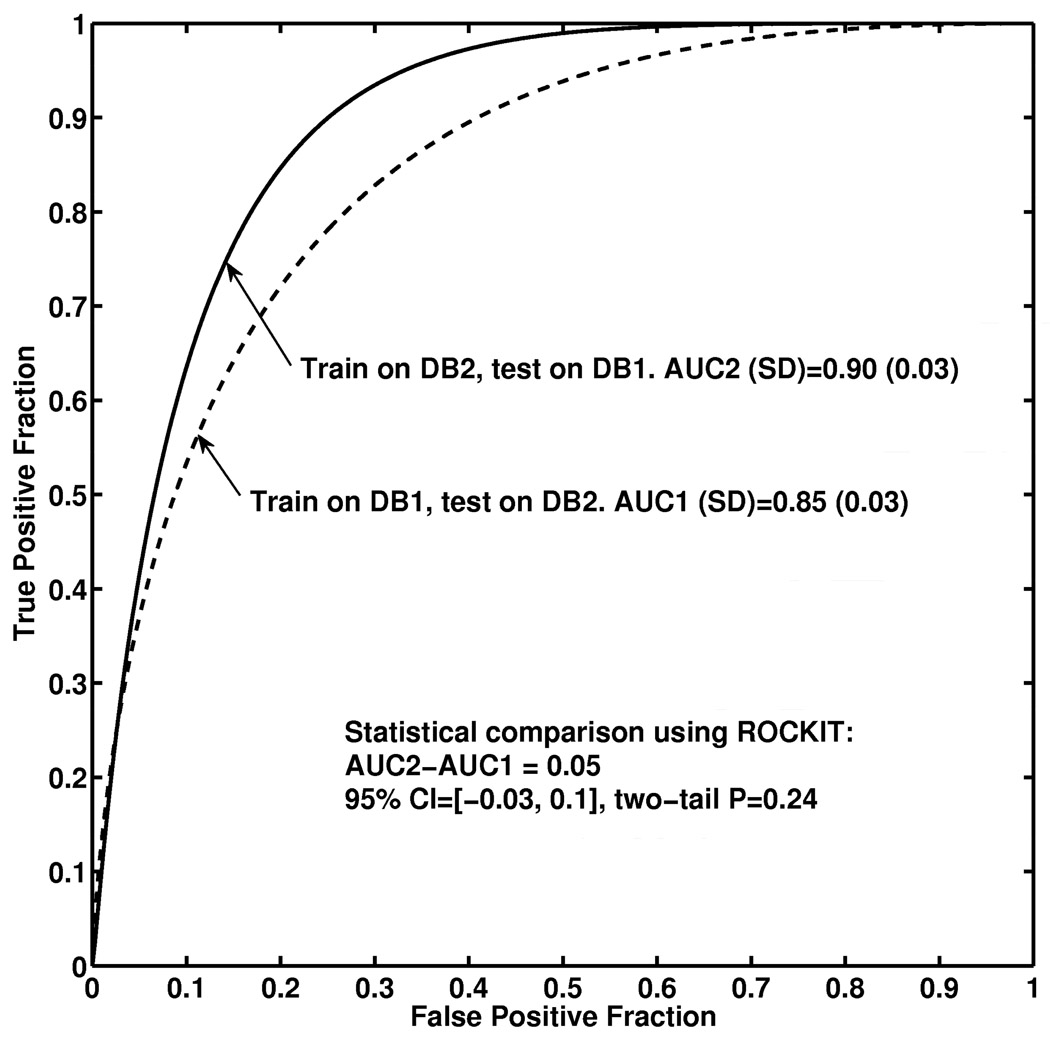

We obtained an AUC of 0.85 (approximate 95% confidence interval (CI): [0.79, 0.91]) for (a) feature selection and classifier training using Database 1 and testing on Database 2; and an AUC of 0.90 (approximate 95% CI: [0.84, 0.96]) for (b) feature selection and classifier training using Database2 and testing on Database1. We failed to observe statistical significance for the difference AUC of 0.05 between the two database-conditions (P=0.24; 95% confidence interval [− 0.03, 0.1]).

Conclusion

These results demonstrate the robustness of our computerized classification system in the task of distinguishing between malignant and benign breast lesions on DCE-MRI images from two manufacturers. Our study showed the feasibility of developing a computerized classification system that is robust across different scanners.

Keywords: computer-aided diagnosis, breast MRI, robustness

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is being increasingly used in clinical practice for the detection and characterization of breast cancer (1–6). The American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN) Trial 6667 Investigators Group has recently reported that MRI can detect cancer that is missed by mammography and clinical examination at the time of the initial breast-cancer diagnosis (3). In 2007, the American Cancer Society published guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography (4) in high risk women. The expanding clinical applications of breast MRI call for developments of advanced computer tools to assist the radiologists in image interpretation and patient workup. First, computer-aided analysis may improve diagnostic accuracy as well as reduce intra- and inter-observer variability as it does in traditional modalities (7–10): there is evidence that computerized analysis of breast MR images complements clinical reading (11). Furthermore, a typical breast MRI study acquires a substantial amount of four-dimensional data, and navigation and interpretation of these large datasets is time-consuming and even challenging for radiologists (12–13). These reasons have motivated us to investigate computerized techniques for breast MR image analysis (14–17).

Historically, researchers and clinicians started performing breast MRI at the two ends of the spectrum of imaging techniques: one used high temporal resolution techniques attempting to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions by enhancement characteristics (called the “dynamic school” in a review by Kuhl et al. (18)), whereas another (called the “static school” (18)) used high spatial resolution techniques attempting to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions by characteristic morphological features. This disparity was mainly due to technical limitations and tradeoffs between spatial and temporal resolution taken at different institutions. Correspondingly, computerized breast lesion characterization in MR images has been an active area of research for many years (19–33) and many of these studies have focused on some particular characteristic features of breast lesions on MR images. Recent multi-center studies (34) and clinical consensus (35–36) have shown that both morphological and kinetic features are important and should be combined in breast MR image lesion characterization. Consensus has also been reached, in principle, that breast MR images should be obtained with both fairly high spatial resolution and fairly high temporal resolution, which is achievable now due to technical progress in recent years (1). However, the image acquisition protocol for breast MRI is not yet standardized across manufacturers and institutions (1). This fact raises the question about the robustness of a computerized image analyses to different MRI scanners or acquisition parameters – a question that is insufficiently studied in the current literature.

In this research, we conducted a pre-clinical evaluation of our computerized system, which takes a suspicious breast lesion identified by radiologists as input and performs automatic lesion segmentation and characterization in order to aid in the discrimination between malignant and benign lesions. Our purpose is to conduct a pre-clinical evaluation of the robustness of our computerized system for breast lesion characterization on two breast MR databases that were obtained from two different MRI scanners.

Materials and Methods

Breast MRI databases

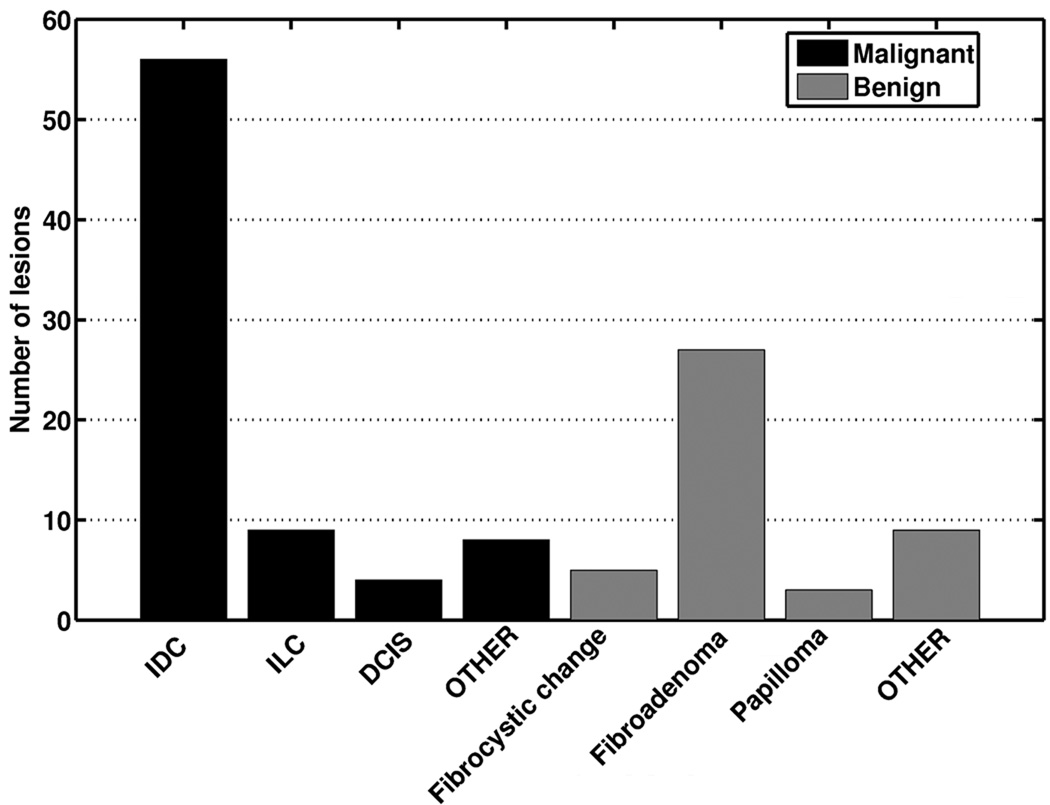

Two breast MR image databases were retrospectively collected under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) for this Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant study. Informed consent was waived. The two databases share similar imaging protocols with slightly different imaging acquisition parameters as summarized in Table 1. Database 1 consisted of 121 primary lesions (mass or nonmass, focus lesions excluded) from 121 patients imaged on a 1.5T Siemens system (Siemens Vision, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). 77 lesions were classified as malignant and 44 lesions as benign based on retrospective review of final pathology reports. The average lesion size was 4.1±0.7 cm3 (range 0.03 cm3 to 78 cm3; median 2.0 cm3). The average age of the patients was 51 years (range 21 to 85; median 50). Database 2 consisted of 181 primary lesions (mass or nonmass, focus lesions excluded) from 161 patients imaged on a 1.5T General Electronic (GE) system (GE medical System, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA). Of these, 97 lesions were classified as malignant and 84 lesions as benign. The average lesion size was 3.4±0.4 cm3 (range 0.09 cm3 to 27 cm3; median 1.2 cm3). The average age of the patients was 52 years (range 24 to 87; median 52). The distribution of lesions by pathologic subtype is shown for both systems in Figure 1. In both databases, fibroadenomas were the most common benign lesion, while invasive ductal carcinomas comprised the majority of malignant lesions. The difference between the average lesion size was not found to be statistically different (two-tailed p value of 0.34 in unpaired t test).

Table 1.

Breast MRI acquisition protocols

| Database 1 | Database 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Scanner | 1.5T Siemens Vision | 1.5T GE Medical System |

| Sequence | T1-weighted 3D spoiled gradient echo sequence | |

| Repetition Time (TR) | 8.1 ms | 7.7 ms |

| Echo Time (TE) | 4 ms | 4.2 ms |

| Fat suppression | No | No |

| Acquisition matrix | 256 × 128 | 256 × 128 |

| Temporal resolution | 69 seconds | 68 seconds |

| Planar spatial resolution | 1.25 mm × 1.25 mm | 1.25 mm × 1.25 mm ~ 1.6 mm× 1.6 mm |

| Slice thickness | 2 mm ~ 3 mm | 3 mm ~ 4 mm |

| View, # slices | Coronal, 64 slices | Coronal, 60 slices |

| Gd-DTPA dose | 0.2 mmol/kg | fixed 20 ml of 0.5 mmol/ml |

| Flow rate | 2 ml/s | |

| Saline Flush | 20 ml | |

| Number of lesions | 77 Malignant, 44 Benign | 97 Malignant, 84 Benign |

Figure 1.

Distribution of patients over their primary lesion pathology for (a) Database 1 and (b) Database 2.

Computerized analysis of breast lesions on MRI images

We have developed a computerized breast MRI analysis system that aims to characterize a suspicious breast lesion as benign or malignant. Once a breast lesion is identified by the radiologist on MR images, the computer performs automatic lesion segmentation and analysis, and outputs an estimated probability of malignancy (Figure 2). In our method, the suspicious lesion is first automatically segmented in 3D. Then, the characteristic kinetic curve (CKC) is automatically identified from the 4D lesion data (i.e., the time course of the 3D lesion). Computerized algorithms are subsequently used to extract image features (i.e., numerical mathematical descriptors) that are useful in the task of distinguishing between malignant and benign lesions. Kinetic features are derived from the computer-identified CKC, morphological features are derived from the 3D lesion segmentation, and texture features are derived from the 3D lesion at the first postcontrast time frame. Finally, a subset of selected features is used to train a neural network that outputs an estimated probability of malignancy. Details of these various stages within the breast MRI CADx workstation are expanded in the next paragraphs.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of our computerized analysis and interpretation scheme.

The breast lesions are automatically segmented in 3D using a fuzzy-c means (FCM) based approach, the details on which we have reported previously (15). As an initial step, a box-shaped volume of interest (VOI) containing the suspicious lesion is selected by a human operator. The postcontrast series of the VOI are normalized voxel-by-voxel by the precontrast intensities. FCM clustering is then applied to partition the voxels in the VOI into two classes, lesion and non-lesion, using the relative-enhancement values of the postcontrast series as a feature vector. Subsequently, a connected-component labeling operation in terms of 3D connectivity is performed to remove the spurious and noisy structures and yield a 3D lesion object. A hole-filling operation is performed on the 3D lesion object to include those lesion voxels with necrosis-induced or noise-related low enhancement. Lesion segmentation by this computerized approach has been found to be highly correlated with the manual delineation by an experienced breast MRI radiologist (15).

The next key step in our approach is to identify the representative kinetic curve of the segmented lesion. A kinetic curve that is generated by simple averaging over the voxels within the entire lesion is suboptimal to characterize the lesion due to inhomogeneity of the contrast agent uptake within the lesion. In the clinical practice, the curve is usually generated from a small region of interest (ROI) drawn manually by clinicians. Visually searching and manually outlining the most-enhancing ROI from 4D data is a time-consuming procedure and is affected by inter- and intra-observer variability. Thus, we had developed an efficient and automatic approach for this curve identification task (16). In our approach, the FCM clustering technique is employed to partition the voxels within the lesion into a number of subsets with each subset having kinetic curves similar to a prototype kinetic curve. The prototype curves are compared and the curve that is most-enhancing at the first postcontrast time-frame is selected as the characteristic kinetic curve (CKC) of the lesion. Kinetic features including the uptake rate, washout rate, time to peak, and maximum uptake are extracted from the CKCs. In the task of distinguishing between benign and malignant lesions, the performance of the kinetic features based on the FCM-identified CKCs was found to be better than that of the features based on the curves obtained by averaging over the entire lesion, and similar to the performance of the features based on kinetic curves generated from regions drawn within the lesion by an experienced radiologist (16).

We also investigated computerized methods for quantifying the morphological and textural characteristics of breast lesions on MR images. Investigation of shape and margin features is motivated by the clinical observation that benign lesions tend to have smooth or lobulated borders, whereas spiculated and irregular margins are indicators of malignancy. A prior study from our group has demonstrated that 3D analyses are more advantageous than 2D analyses for shape and margin features (18).

Investigation of texture features is motivated by the clinical observation that the spatial pattern of contrast enhancement of a malignant lesion tends to be more inhomogeneous than that of a benign lesion. To further quantify the spatial properties of enhancement in breast lesions on MR images, we extended the traditional 2D gray-level co-occurrence matrix method to a volumetric texture analysis approach, which allows extraction of texture features from 3D segmented lesions (17). Compared to the traditional texture feature extraction method that calculates the features from a rectangular ROI containing the lesion, our approach has two advantages: it improves the counting statistics by utilizing the 3D information and it also renders the texture characterization more accurate by excluding the influence of the normal structure that would be included by a regular-shaped ROI. Our results showed that our volumetric approach significantly improved the performance of texture features, as compared to the traditional 2D approach, in the task of distinguishing between malignant and benign lesions (17).

Additionally, spatial-temporal features were extracted to describe the kinetics of spatial variance of the enhancement within the 3D lesion (14).

The qualitative description of all these features (mathematical descriptors) is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of computerized features in the classification of breast lesions on DCE-MRI: “small “(“large”) means malignant lesions tend to have smaller (larger) feature values than do benign ones. “-” means failing to find significant difference of feature values between malignant and benign lesions.

| Feature | Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fk1 | Max. enh. | maximum contrast enhancement | - |

| Fk2 | Time to peak | time frame at which the maximum enhancement occurs | small |

| Fk3 | Uptake rate | uptake speed of the contrast enhancement | large |

| Fk4 | Washout rate | washout speed of the contrast enhancement | large |

| Fk5 | Curve shape index | difference between late and early enhancement | small |

| Fk6 | Max. var. of enh. | maximum variance of contrast enhancement | - |

| Fk7 | Time to peak | time frame at which the maximum variance occurs | small |

| Fk8 | Var. incr. rate | increasing speed of the enhancement-variance | large |

| Fk9 | Var. dec. rate | decreasing speed of the enhancement-variance | large |

| Fm1 | Energy | local image homogeneity | small |

| Fm2 | Contrast | local image variations | large |

| Fm3 | Correlation | image linearity | large |

| Fm4 | Variance | how spread out the gray-level distribution is | large |

| Fm5 | Homogeneity | local image homogeneity | small |

| Fm6 | Sum Average | the overall brightness (average gray-level) | large |

| Fm7 | Sum Variance | how spread out the distribution of the sum of the gray-levels of voxel- pairs is |

large |

| Fm8 | Sum Entropy | the randomness of the sum of gray-levels of neighboring voxels | large |

| Fm9 | Entropy | the randomness of the gray-levels | large |

| Fm10 | Difference Variance | variations of difference of gray-levels between voxel-pairs | large |

| Fm11 | Difference Entropy | the randomness of the difference of neighboring voxels’ gray-levels | large |

| Fm12 | IMC1 | nonlinear gray-level dependence | small |

| Fm13 | IMC2 | nonlinear gray-level dependence | large |

| Fm14 | Max Corr. coeff. | nonlinear gray-level dependence | large |

| Fm15 | Circularity | similarity of lesion shape to an effective sphere | small |

| Fm16 | Irregularity Margin | deviation of 3D lesion surface from a sphere surface | large |

| Fm17 | sharpness Var. of | mean of the image gradient at the lesion margin | small |

| Fm18 | margin sharpness | variance of the image gradient at the lesion margin | small |

| Fm19 | Variance of RGH | indicates how well the enhancement structures in a VOI extend in a radial pattern originating from the center of the VOI |

small |

Computerized classification of breast lesions on MRI images

Computerized classification is performed using an automatic classifier to combine multiple features into a numerical index, i.e., an estimated probability of malignancy. A feature selection step is needed to reduce the dimensionality of the feature space and hence reduce the complexity of the classifier. In this task, we used a Bayesian neural network (BNN) with automatic relevance determination (ARD) priors for joint feature selection and classification. BNN with ARD priors has been investigated and described in the literature (37–40) and its use in medical imaging has been demonstrated (41). In this approach, a hierarchical model is designed to use a group of hyperparameters to control the magnitude of the neural network weight parameters. In particular, each feature has a hyperparameter that indicates the relevance of this feature to the classifier output – the larger the hyperparameter, the less relevance of the feature.

A subset of the most relevant features can then be used to train the neural network to estimate the probability of malignancy, which evaluated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. The area under the ROC curve, or AUC, is used as a performance figure of merit in the task of distinguishing between malignant and benign breast lesions. The ROCKIT software (42) was used in our analyses.

To evaluate the robustness of our classification system, we first used Database 1 (DB1) for feature selection and classifier training, and used Database 2 (DB2) as a test dataset to assess the performance of the trained classifier. Then, we exchanged the training/test role of the two datasets and repeated the process. The repetition is an independent and identical procedure except switching the role of the two datasets, i.e., the results in the first training/test procedure were not employed in any way (e.g., adjusting classifier parameters) in the repeated procedure.

Results

We used the BNN with ARD priors to determine the relevance of the 28 features under investigation. For clarity, Figure 3 (a) shows the relative importance of the top 14 features as determined by training the BNN with ARD priors using DB1. Figure 3 (b) shows the corresponding results for DB2. Between the two databases (DB1 and DB2), 8 features were commonly ranked as among the top 14 features. Although the kinetic feature (Fk2) is ranked as the most relevant feature by both datasets, other features are not ranked in the exact same order.

Figure 3.

The relative importance of computerized image features to the classification task as assessed by the Bayesian neural network model with automatic relevance determination priors using (a) Database 1; and (b) Database 2. The results for the top-ranked 14 features are plotted. See Table 2 for the definition of the features.

We then examined the classification performance of BNN using the top N (N=2,3,…,28) features as input. The following results are shown in Figure 4: (a) feature selection and classifier training using DB1 and testing the classifier on DB2; (b) feature selection and classifier training using DB2 and testing the classifier on DB1; (c) feature selection and classifier training using DB1 and testing the classifier on DB1; (d) feature selection and classifier training using DB2 and testing the classifier on DB2. The results in (a) and (b) represent the assessment on independent datasets whereas the results in (c) and (d) represent resubstitution results that are optimistically biased. It is observed from Figure 4 that when the number of features is above 10, the AUC achieves a plateau for all four conditions with average AUC values of 0.84, 0.90, 0.95, 0.92, for (a), (b), (c), and (d) respectively.

Figure 4.

The classification performance of the computerized system as a function of the number of top-ranked features.

We then used ROCKIT to perform a statistical comparison of the two “independent assessment” conditions (a) and (b) when the top 14 features were used and the results are plotted in Figure 5. We obtained an AUC of 0.85 for condition (a) and an AUC of 0.90 for condition (b). We failed to observe statistical significance for the difference AUC of 0.05 between the two conditions (P=0.24; 95% confidence interval [−0.03, 0.1]).

Figure 5.

ROC curves and statistical comparison of the two “independent assessment” conditions: (a) feature selection and classifier training using DB1 and testing the classifier on DB2 (dash); (b) feature selection and classifier training using DB2 and testing the classifier on DB1 (solid).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate the robustness of our computerized classification system in the task of distinguishing between malignant and benign breast lesions on DCE-MRI images. Both independent assessments—that is, training on one distinct database and evaluating performance on another— yielded fairly high classification performances, the difference between which shows no statistical significance. The two datasets were obtained in two institutions on scanners from two different manufacturers. The two scanners used a similar MR imaging protocol with slightly different image acquisition parameters and different contrast agent dosage. The significance of the study showed the feasibility of developing computerized classification system that is robust across different scanners.

It should be noted that the failure to observe statistically significant difference does not mean that the difference may not actually exist (43). The retrospective analysis of the two existing datasets may have limited the ability to demonstrate the robustness of our technique because the different mix of lesion subtypes in the two datasets (see Figure 1) may have contributed to the observed performance difference. Despite this limitation, the results still show encouraging degree of robustness. Although the conclusion may not be directly generalizable to all MR imaging protocols in current clinical practice, the computer characterization architecture of the system may be applicable to other imaging protocols. For example, the classifier can be re-trained for the system to be used on a different imaging protocol.

Indeed, image acquisition protocols in breast MR imaging are not standardized and optimal imaging parameters are still under investigation (1) (44). This is probably the fundamental obstacle at present for the development of computerized systems since a computerized system is typically designed on a dataset available from a specific institution and/or manufacturer, and robustness concerns can always be raised when a newly-designed protocol is introduced to clinical practice. Research on the standardization and optimization of breast MR imaging protocols using methods such as the task-based approach outlined in (45) are expected to facilitate the development of computerized analysis systems.

The imaging technique used in our study is similar to that launched by Kaiser et al. (46) , called “the archetype of dynamic breast MRI” by Kuhl et al. (18), which involves acquisition of one precontrast and a series of postcontrast images of both breasts at a temporal resolution of roughly 60 seconds. This type of breast MR image acquisition sequence has the advantage of being able to provide both morphological and kinetic information from one MRI examination, and was representative of early dynamic MR protocols. However, due to technical limitations, both the spatial resolution and the temporal resolution are moderate in this protocol. A recent study by Schnall et al. (12) reported on a multicenter breast MR imaging study in which a “double exam” protocol was used. In their study, subjects were scanned with a contrast-enhanced 3D T1-weighted gradient echo sequence with high spatial resolution (minimum spatial resolution of 0.7×1.4 ×3 mm). Subsequently, patients with suspicious findings were asked to return for a 2D dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging with a temporal resolution of 15 seconds. The computerized morphological features and kinetic features that we have derived may have improved diagnostic performance when applied to MR images with improved spatial resolution and improved temporal resolution.

The BNN model with ARD priors provides the flexibility for joint feature relevance determination and classification. However, an optimal subset of features may not be determined uniquely for a number of reasons. First, it is possible that different sets of features may yield similar classification performances on the population, i.e. with infinite data to perform the feature selection. Second, due to the use of a finite size data sample, even if there exists a unique optimal subset of features for a population, a feature selector would select the optimal subset only with some certain probability less than 1 due to the uncertainty in the individual performance of each feature (47). Third, in practice, different datasets may not represent an actual random sample from the same population, thus increasing the variability in the feature selection results. The observed discrepancy between Figure 3(a) and Figure 3(b) may be due to all these reasons. A large dataset would help improve the consistency of feature selection.

In addition, the BNN model with ARD priors that we used only provided the relevance (or relative importance) of the features, with the number of features being chosen by the user. Without defining further objective criterion for this judgment, one cannot use the assessment results on clinical datasets such as those in Figure 4 to determine the exact number of features for practical applications. In this application, one may arbitrarily choose between 10 and 14, since, within this range, we observed no substantial decrease of performance due to increasing the complexity or reducing the feature set. Increasing the patient sample size would definitely reduce this ambiguity.

The output of the BNN is an estimate of the a posteriori probability of malignancy (48). It should be noted that the use of AUC is an assessment of the diagnostic accuracy or the discrimination ability of the BNN, but not an assessment of the absolute value or the calibration of the BNN output (49). In addition, for clinical use of such probability estimates, some adjustment of the BNN output may be needed to reflect the actual clinical prevalence of malignancy (50). The assessment of calibration and clinical adjustment are beyond the scope this paper.

Our datasets were collected from a consecutive series of patients with known breast lesions planned for open (surgical) biopsy, which explains the relative high number of malignant cases compared to benign lesions. Although the focus of this paper is on diagnostic work-up applications, the techniques have potential to be extended to other clinical applications, such as classification of lesions beyond the two primary classes to multiple subtypes of cancers, high-risk screening, and preoperative staging.

Patient motion during image acquisition may introduce inaccuracies in kinetic features. Cases with abrupt and large patient movements between dynamic series had been clinically treated as acquisition failure and were excluded from our datasets. In our datasets, only patient respiratory motion was observed. The motion mostly resulted in additional blurring rather than actual displacement of image structure. However, it is important to note that image alignment of breast volumes at different time frames may improve the accuracy of our analyses.

In conclusion, in this pre-clinical evaluation, we have demonstrated the robustness of our computerized classification system across two different scanners in the task of distinguishing between malignant and benign breast lesions on DCE-MR images. The system is potentially useful to aid radiologists in the characterization and interpretation of breast MR images. For actual clinical applications, a clinical study for both stand-alone and observer performance evaluations are needed with a prospective design on a target population (screening or diagnosis) and a sufficiently large random sample of patients from that population.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in parts by NIH R33-113800, P50-CA125183, and a DOE grant DE-FG02-08ER6478.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

M.L.G. is a stockholder in R2 Technology/Hologic and receives royalties from Hologic, GE Medical Systems, MEDIAN Technologies, Riverain Medical, Mitsubishi and Toshiba. It is the University of Chicago Conflict of Interest Policy that investigators disclose publicly actual or potential significant financial interest that would reasonably appear to be directly and significantly affected by the research activities.

Certain commercial materials and equipment are identified in order to adequately specify experimental procedures. In no case does such identification imply recommendation or endorsement by the FDA, nor does it imply that the items identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

References

- 1.Kuhl CK. Current status of breast MR imaging. Part 1. Technical issues. Radiology. 2007;244:356–378. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2442051620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhl CK. Current status of breast MR imaging. Part 2. Clinical applications. Radiology. 2007;244:672–691. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2443051661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehman CD, Gatsonis C, Kuhl CK, Hendrick RE, Pisano ED, Hanna L, Peacock S, Smazal SF, Maki DD, Julian TB, DePeri ER, Bluemke DA, Schnall MD ACRIN Trial 6667 Investigators Group. MRI evaluation of the contralateral breast in women with recently diagnosed breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1295–1303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, Harms S, Leach MO, Lehman CD, Morris E, Pisano E, Schnall M, Sener S, Smith RA, Warner E, Yaffe M, Andrews KS, Russell CA American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75–89. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeMartini W, Lehman C, Partridge S. Breast MRI for Cancer Detection and Characterization: A Review of Evidence-Based Clinical Applications. Acad Radiol. 2008;15:408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eyal E, Degani H. Model-based and model-free parametric analysis of breast dynamic-contrast-enhanced MRI. NMR in biomedicine. 2009;22:40. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huo Z, Giger ML, Vyborny CJ, Metz CE. Breast cancer: effectiveness of computer-aided diagnosis observer study with independent database of mammograms. Radiology. 2002;224:560–568. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2242010703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan HP, Sahiner B, Helvie MA, et al. Improvement of radiologists’ characterization of mammographic masses by using computer-aided diagnosis: an ROC study. Radiology. 1999;212:817–827. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.3.r99au47817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang Y, Nishikawa RM, Schmidt RA, Metz CE, Giger ML, Doi K. Improving breast cancer diagnosis with computer-aided diagnosis. Acad Radiol. 1999;6:22–33. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(99)80058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang Y, Nishikawa RM, Schmidt RA, Toledano AY, Doi K. Potential of computer-aided diagnosis to reduce variability in radiologists’ interpretations of mammograms depicting microcalcifications. Radiology. 2001;220:787–794. doi: 10.1148/radiol.220001257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deurloo EE, Muller SH, Peterse JL, Besnard AP, Gilhuijs KG. Clinically and mammographically occult breast lesions on MR images: potential effect of computerized assessment on clinical reading. Radiology. 2005;234:693–701. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2343031580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnall MD. Clinical applications of image analysis and visualization for three dimensional breast imaging. In: Armato SG III, Brown MS, editors. Multidimensional image processing, analysis, and display: RSNA categorical course in diagnostic radiology physics. RSNA; 2005. pp. 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilhuijs KG. Computer-supported analysis of breast MR imaging in four dimensions: why, when, and how. In: Armato SG III, Brown MS, editors. Multidimensional image processing, analysis, and display: RSNA categorical course in diagnostic radiology physics. RSNA; 2005. pp. 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen W, Giger ML, Lan L, Bick U. Computerized interpretation of breast MRI: Investigation of enhancement-variance dynamics. Med Phys. 2004;31:1076–1082. doi: 10.1118/1.1695652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen W, Giger ML, Bick U. A fuzzy c-means (FCM) based approach for computerized segmentation of breast lesions in dynamic contrast-enhanced MR images. Acad Radiol. 2006;16:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen W, Giger ML, Bick U, Newstead GM. Automatic identification and classification of characteristic kinetic curves of breast lesions on DCE-MRI. Med Phys. 2006;33:2878–2887. doi: 10.1118/1.2210568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen W, Giger ML, Li H, Bick U, Newstead GM. Volumetric texture analysis of breast lesions on contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance images. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:562–571. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhl CK, Schild HH. Dynamic image interpretation of MRI of the breast. J. Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12:965–974. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200012)12:6<965::aid-jmri23>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayton P, Brady M, Tarassenko L, Moore N. Analysis of dynamic MR breast images using a model of contrast enhancement. Medical Image Analysis. 1997;1:207–224. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(97)85011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilhuijs KG, Giger ML, Bick U. Computerized analysis of breast lesions in three dimensions using dynamic magnetic-resonance imaging. Med Phys. 1998;25:1647–1654. doi: 10.1118/1.598345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penn AI, Bolinger L, Schnall MD, Loew MH. Discrimination of MR images of breast masses with fractal-interpolation function models. Acad Radiol. 1999;6:156–163. doi: 10.1016/S1076-6332(99)80401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucht RE, Knopp MV, Brix G. Classification of signal-time curves from dynamic MR mammography by neural networks. Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;19:51–57. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(01)00222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibbs P, Turnbull LW. Textural analysis of contrast-enhanced MR images of the breast. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:92–98. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szabó BK, Wiberg MK, Boné B, Aspelin P. Application of artificial neural networks to the analysis of dynamic MR imaging features of the breast. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:1217–1225. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Twellmann T, Lichte O, Nattkemper TW. An adaptive tissue characterization network for model-free visualization of dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image data. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2005;24:1256–1266. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2005.854517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penn AI, Thompson S, Brem R, Lehman C, Weatherall P, Schnall M, Newstead G, Conant E, Ascher S, Morris E, Pisano E. Morphologic blooming in breast MRI as a characterization of margin for discriminating benign from malignant lesions. Acad Radiol. 2006;13:1344–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmid VJ, Whitcher B, Padhani AR, Taylor NJ, Yang GZ. Bayesian methods for pharmacokinetic models in dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2006;25:1627–1636. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2006.884210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams TC, DeMartini WB, Partridge SC, Peacock S, Lehman CD. Breast MR imaging: computer-aided evaluation program for discriminating benign from malignant lesions. Radiology. 2007;244:94–103. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2441060634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meinel LA, Stolpen AH, Berbaum KS, Fajardo LL, Reinhardt JM. Breast MRI lesion classification: Improved performance of human readers with a back propagation neural network computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) system. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25:89–95. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woods BJ, Clymer BD, Kurc T, Heverhagen JT, Stevens R, Orsdemir A, Bulan O, Knopp MV. Malignant-lesion segmentation using 4D co-occurrence texture analysis applied to dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance breast image data. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2007;25:495–501. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levman J, Leung T, Causer P, Plewes D, Martel AL. Classification of Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Breast Lesions by Support Vector Machines. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2008;2:688–696. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2008.916959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nie K, Chen JH, Yu HJ, Chu Y, Nalcioglu O, Su MY. Quantitative analysis of lesion morphology and texture features for diagnostic prediction in breast MRI. Acad Radiol. 2008;15:1513–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLaren CE, Chen WP, Nie K, Su MY. Prediction of malignant breast lesions from MRI features: a comparison of artificial neural network and logistic regression techniques. Acad Radiol. 2009;16:842–851. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schnall MD, Blume J, Bluemke DA, DeAngelis GA, DeBruhl N, Harms S, Heywang-Köbrunner SH, Hylton N, Kuhl CK, Pisano ED, Causer P, Schnitt SJ, Thickman D, Stelling CB, Weatherall PT, Lehman C, Gatsonis CA. Diagnostic architectural and dynamic features at breast MR imaging: multicenter study. Radiology. 2006;238:42–53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2381042117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ikeda DM, Hylton NM, Kinkel K, Hochman MG, Kuhl CK, Kaiser WA, Weinreb JC, Smazal SF, Degani H, Viehweg P, Barclay J, Schnall MD. Development, standardization, and testing of a lexicon for reporting contrast-enhanced breast magnetic resonance imaging studies. J. Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13:889–895. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American College of Radiology. ACR BIRADS: Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System: breast imaging atlas. Reston, VA: 2003. ACR BI-RADS: MRI. [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacKay DJS. PhD thesis, California. Pasadena, CA: Institute of Technology; 1992. Bayesian Methods for Adaptive Models. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neal RM. Lecture notes in statistics. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1996. Bayesian learning for neural networks. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bishop CM. Neural Networks for Pattern Recognition. Oxford, U.K: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nabney T. Netlab: Algorithms for Pattern Recognition. London, U.K: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen W, Zur RM, Giger ML. Joint feature selection and classification using a Bayesian neural network with “automatic relevance determination” priors: potential use in CAD of medical imaging. Proceedings of SPIE, Medical Imaging 2007: Computer-aided diagnosis. Vol. 6514:65141G. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Metz CE, Herman BA, Shen JH. Maximum likelihood estimation of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves from continuously-distributed data. Stat Med. 1998;17:1033–1053. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980515)17:9<1033::aid-sim784>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Metz CE. Quantification of failure to demonstrate statistical significance: the usefulness of confidence intervals. Invest Radiol. 1993;28:59–63. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199301000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jansen SA, Shimauchi A, Zak L, Fan X, Wood AM, Karczmar GS, Newstead GM. Kinetic curves of malignant lesions are not consistent across MR systems: the need for improved standardization of breast Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI acquisitions. Am. J. Roentg. 2009;193:832–839. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barrett HH, Myers KJ. Foundations of Image Science. Wiley-Interscience; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaiser WA, Zeitler E. MR imaging of the breast: fast imaging sequence with and without Gd-DTPA. Radiology. 1989;170:681–686. doi: 10.1148/radiology.170.3.2916021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kupinski MA, Giger ML. Feature selection with limited datasets. Med. Phys. 1999;26:2176–2182. doi: 10.1118/1.598821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kupinski MA, Edwards DC, Giger ML, Metz CE. Ideal observer approximation using Bayesian classification neural networks. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2001;20:886–899. doi: 10.1109/42.952727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cook NR. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation. 2007;115:928–935. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.672402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horsch K, Giger ML, Metz CE. Prevalence scaling: Applications to an intelligent workstation for the diagnosis of breast cancer. Acad Radiol. 2008;15:1446–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]