Abstract

Because many serious adolescent offenders reduce their antisocial behavior after court involvement, understanding the patterns and mechanisms of the process of desistance from criminal activity is essential for developing effective interventions and legal policy. This study examined patterns of self-reported antisocial behavior over a 3-year period after court involvement in a sample of 1,119 serious male adolescent offenders. Using growth mixture models, and incorporating time at risk for offending in the community, we identified five trajectory groups, including a “persister” group (8.7% of the sample) and a “desister” group (14.6% of the sample). Case characteristics (age, ethnicity, antisocial history, deviant peers, a criminal father, substance use, psychosocial maturity) differentiated the five trajectory groups well, but did not effectively differentiate the persisting from desisting group. We show that even the most serious adolescent offenders report relatively low levels of antisocial activity after court involvement, but that distinguishing effectively between high-frequency offenders who desist and those who persist requires further consideration of potentially important dynamic factors related to this process.

There is broad recognition of the potential of longitudinal data to inform the study of juvenile crime and delinquency. Over the last few decades, researchers concerned with the development of antisocial behavior have produced many large prospective studies worldwide (see Thornberry & Krohn, 2003) and numerous secondary analysis projects (e.g., Broidy et al., 2003; Sampson & Laub, 1993). The introduction and refinement of new methodological and statistical techniques, particularly trajectory modeling (Muthén & Muthén, 2000; Nagin, 1999, 2005; Piquero, 2008), have fueled these efforts, allowing researchers to directly examine group-based patterns of antisocial behavior over time. These efforts have clarified our understanding of the course of particular behavioral patterns over different periods of development (e.g., the stability of aggressive behavior; Coie & Dodge, 1998; Piquero, Farrington, & Blumstein, 2003), and the importance of particular events at different ages for promoting onset or maintenance of antisocial activity (e.g., Kokko, Tremblay, Lacourse, Nagin, & Vitaro, 2006; Patterson & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1984).

Panel studies have considerable potential for helping juvenile justice and child welfare professionals formulate more informed identification of at-risk groups and more focused preventive interventions (Mulvey & Woolard, 1997). Existing longitudinal research is minimally useful, however, in providing a clear picture of the offending patterns of adolescents who are in the juvenile justice system, especially serious adolescent offenders, an important group for the development of criminological theory and juvenile justice policy (Laub & Sampson, 2001). In general, extant studies have been directed mainly toward mapping out developmental regularities connected with the onset and maintenance of antisocial behavior, providing a picture of when and how particular children veer off the path of normal development to ones of high rates of antisocial activity (at least for an extended time period). More specifically, longitudinal studies of antisocial behavior usually have followed cohorts of children and adolescents sampled from schools or communities, sometimes oversampling those with high-risk status to provide adequate numbers of both subjects who will and will not display problem behaviors. Even with oversampling, though, this approach usually yields only a small number of adolescents who end up penetrating deeply into the juvenile justice system (Elliott & Huizinga, 1987). Accordingly, there is limited information about the specific developmental contexts and behavioral characteristics that differentiate among adolescents whose offending is most serious.

We were only able to identify six previous trajectory studies undertaken with samples of adjudicated offenders. Three different data sets have been used, and all subjects were followed through portions of adulthood. Three studies employ the sample of Boston area delinquents studied by the Gluecks (Eggleston, Laub, & Sampson, 2004; Laub, Nagin & Sampson, 1998; Sampson & Laub, 2003), two involve cohorts of California Youth Authority parolees (Piquero et al., 2001; Piquero, MacDonald, & Parker, 2002), and one uses an offenders’ index from the British Home Office (Francis, Soothill, & Fligelstone, 2004). Although important, these studies are limited in four ways: (a) they tend to employ only official records of offending, (b) they are based on a single site, (c) they contain primarily White subjects (with the exception of the California Youth Authority parolees), and (d) they contain a limited number of important and relevant theoretical predictors that have been found to be associated with antisocial and criminal activity over the life course.

Information about patterns of change over time in serious offenders, if available, would be of enormous value, because it is the starting point for mapping out the process of desistance from involvement in antisocial activity (Ezell & Cohen, 2005; Laub & Sampson, 2001). Longitudinal research has repeatedly documented that less than half of serious adolescent offenders likely will continue their adult criminal career into their 20s (see Elliott, 1994; Piquero et al., 2001; Redding, 1997). Describing the pathways out of involvement in antisocial activity (and the justice system) and identifying the key factors related to desistance constitute major questions that have received only limited attention from researchers.

Purpose of the Present Study

The present article draws on data from an ongoing, large-scale, prospective study of a cohort of serious juvenile offenders, the Pathways to Desistance study (see Mulvey et al., 2004). The primary aim of the analyses presented here is to provide a portrait of the offending patterns of a group of serious adolescent offenders in the period following court adjudication. It addresses the basic question of how much and what type of variability might exist in adolescent offenders at the deepest end of the juvenile justice system. Knowing the trajectories of these offenders in the critical period after their court involvement provides valuable information for focusing assessment and intervention strategies with these individuals. We also examine the power of background characteristics to differentiate serious adolescent offenders who follow different behavioral pathways through this time period. In short, this study provides a unique opportunity to address the limitations of previous longitudinal studies of serious juvenile offenders: it contains a comprehensive, soundly measured, and generally complete set of both predictor and outcome measures on a sample of serious adolescent offenders from two major metropolitan areas.

Our focus in this article is on characteristics of offenders that predict patterns of offending and desistance, and not on the impact of various types of interventions on these same outcomes. In the present analyses, we estimate the extent, types, and magnitude of heterogeneity of subsequent patterns of antisocial behavior among serious offenders, and whether this heterogeneity is meaningfully related to individuals’ developmental histories and life circumstances at the time of court adjudication. Taking on the ambitious task of thoroughly mapping out the desistance process also requires an examination of the sanctioning and treatment experiences of offenders while in the system as well as their experiences in the community in closely spaced intervals while on probation or after release from secure confinement. Static characteristics alone will be insufficient to differentiate subgroups who follow different patterns of offending behavior (Nagin & Tremblay; 2005; Piquero, 2008; Sampson & Laub, 2005). Nonetheless, examining relations between offender characteristics and patterns of offending are valuable leads for framing future research on the desistance process and the development of possible screening tools for disposition decision making and risk management. The present analysis takes the first step in addressing this broader goal.

In the present study, trajectory analysis approaches are used to determine if there are identifiable subgroups of serious adolescent offenders with different patterns of self-reported offending during a 3-year follow-up period following adjudication. Although the use of group-based trajectory modeling among criminologists has been both widely employed and controversial (Piquero, 2008), we believe that the enterprise of identifying groups of individuals with different overtime patterns of offending is a useful endeavor, both heuristically and practically. Clearly, solutions obtained in any individual analysis (including this one) are dependent on the characteristics of the sample examined, the outcome measures used, and the length of the follow-up period (see Eggleston et al., 2004; Piquero et al., 2001; Roeder, Lynch, & Nagin, 1999). However, trajectory solutions can identify individuals within meaningful populations, such as the sample for this study, who share common behavior patterns over time.

Factors Predicting Subgroup Membership

In addition to estimating distinct offending trajectories, our interest in this article is in the relation between patterns of offending and numerous theoretically relevant factors that have been associated with continued offending in previous investigations, but rarely studied within large samples of juveniles who have been adjudicated of serious offenses. The universe of possible variables to consider as predictors of continued offending is long, and no single study could hope to be exhaustive in its coverage. Following a comprehensive review of the most common and important risk or protective factors associated with adolescent offending (Loeber & Farrington, 1998), we examined a set of variables indicative of an individual’s risk or propensity for future offending (“case characteristics”) and a set of variables reflecting potentially criminogenic social contexts (“social context characteristics”). This approach allowed us to examine the relative influence of both personal and environmental characteristics simultaneously, and to consider contemporary theoretical models that have been tested under a wide range of sampling and measurement conditions. A central question of this inquiry is whether the factors associated with patterns of adolescent offending in prior studies using population samples of adolescents are also predictive of desistance within a sample of serious adolescent offenders.

Case characteristics

Four sets of individual characteristics were examined: (a) criminal history, (b) substance use and mood disorders, (c) attitudes toward the law, and (d) psychosocial maturity. Much prior research on antisocial behavior in community and high-risk samples indicates that individuals with a history of offending, substance use, and other mental health problems, cynical attitudes toward the legitimacy of the law, and psychosocial immaturity, especially problems in self-regulation, are at great risk for continued involvement in antisocial activity. However, to our knowledge, no studies have examined these factors simultaneously, in conjunction with the contextual variables we describe below, or in a sample of serious offenders over a lengthy study interval that spans developmental transitions from adolescence into adulthood.

The first set of factors, which is the most influential factor in judges’ disposition decisions, concerns the offender’s prior history of offending and arrest. A large literature (Campbell & Schmidt, 2000; Hoge, Andrews, & Leschied, 1995; Horwitz & Wasserman, 1980; Matarazzo, Carrington, & Hiscott, 2001; Thomas & Cage, 1977), including our own analyses with this sample (Cauffman et al., 2007), indicates that dispositional decisions in contemporary juvenile courts are based mainly on the type and severity of the current offense and the individual’s prior record, even when the adolescents considered are restricted to serious offenders (thus limiting the heterogeneity of these two variables). Accordingly, in the present set of analyses we ask whether individuals with a history of relatively more serious antisocial behavior, as indexed both by juveniles’ self-reports of offending prior to their current adjudication and their official prior arrest record, are more likely to follow a trajectory of continued offending than their peers.

The second set of individual case characteristics characterizes individuals’ use and abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs (see Fagan, 1990) and their mood or anxiety problems (Grisso, 2004). A growing body of evidence indicates a high degree of comorbidity of substance use problems (i.e., high or problematic levels of substance use or the presence of a diagnosable substance use disorder of dependence or abuse) and delinquency (i.e., high rates of self-reported criminal behavior or official arrest) in adolescence, with about half of all serious juvenile offenders having substance use problems (Grisso, 2004). There is also evidence that substance use at one age is a highly consistent indicator of continued serious offending at a later age (D’Amico, Edelen, Miles, & Morral, 2008; Dembo, Wareham, & Schmeidler, 2007) and that crime and substance use fluctuate together over time (Sullivan & Hamilton, 2007), suggesting a reciprocal relationship between the two behaviors.

Affective disorders also have a demonstrated connection to involvement in delinquent behavior. Affective states such as depression or anxiety can often be manifested in adolescents as anger, leading to increased involvement in violent acts toward others (Mattila, Parkkari, & Rimpela, 2006). In addition, disproportionately higher rates of affective disorders have been observed in samples of juvenile offenders (Abram, Teplin, McClelland, & Dulcan, 2003). Although less is known about the relation between delinquency and affective psychopathology over time, it seems reasonable to assume that there is a substantial relation between the two (McReynolds et al., 2008).

The third set of individual predictors includes individuals’ attitudes and values about antisocial behavior and beliefs about the law, law authorities, and legal institutions; sometimes referred to as “legal socialization” (Fagan & Tyler, 2005; Sampson & Bartusch, 1998; Tapp & Kohlberg, 1971; Tyler & Huo, 2002). Attitudes about the acceptability of antisocial activity to achieve desired ends or the elevation of one’s own interests above the obligations of the social contract have long been considered a central component of the character of a repeat offender (Samenow, 1996). More specific attitudes about the legitimacy of the legal system have also been linked to individuals’ inclination to follow a law-abiding lifestyle (Tyler, 1990, 1997) and to cooperate with police and other legal actors (Tyler & Fagan, 2008). Our own analyses of legal socialization within the current sample indicates quite clearly that offenders differ significantly in their views of the law and legal system prior to their adjudication, that these differences are stable for a significant period after adjudication (Piquero, Fagan, Mulvey, Steinberg, & Odgers, 2005), and that the changes that do occur in these beliefs are related logically to perceptions of deterrence and the costs and benefits of crime as well as the risk of detection and punishment (Fagan & Piquero, 2007).

The final set of personal factors includes variables that index individual differences in aspects of psychosocial maturity that have been hypothesized to affect antisocial behavior. The most influential theory of the underlying individual causes of individual differences in antisocial behavior within criminology is Gottfredson and Hirschi’s (1990) General Theory of Crime. According to this view, the only significant individual predictor of criminal activity is low self-control, defined as the “tendency to pursue short-term, immediate pleasure” to the neglect of long-term consequences (p. 93). For Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990), self-control is, “for all intents and purposes, the individual-level cause of crime” (emphasis in original, p. 232) and is believed to stably predict criminal acts throughout the life course (Hirschi & Gottfredson, 1995), a position that has received extensive support in prior research (Pratt & Cullen, 2000). Deficiencies in self-control within a sample of serious offenders should distinguish individuals who continue offending from those who desist from antisocial behavior over time (Cauffman, Steinberg, & Piquero, 2005; Monahan, Steinberg, Cauffman, & Mulvey, in press).1 We also include other indicators of psychosocial maturity that have been linked to adolescent antisocial behavior, such as responsibility, perspective taking, and susceptibility to peer pressure (see Cauffman & Steinberg, 2002). These constructs, indicating key perceptual abilities associated with successful transition from adolescence to early adulthood roles, have been investigated in numerous normative studies and ones linking these skills to increased likelihood of involvement in risky and antisocial behaviors (e.g., Steinberg et al., 2008, 2009).

Social contexts

Theories of contextual influences on offending have focused on family, peers, and community as interrelated factors that increase the likelihood of involvement in antisocial behavior (Chung & Steinberg, 2006). It has been shown that adolescents are more likely to engage in antisocial behavior when they are exposed to harsh or lax parenting, when they affiliate with delinquent peers, and when they grow up in neighborhoods characterized by poverty, disorganization, and low “collective efficacy” (Farrington, 2004; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2004; Loeber & Farrington, 1998). Cross-sectional analyses of data on histories of offending within the current sample indicate, in fact, that offenders from contexts characterized by poor parenting, deviant peer groups, and neighborhood disadvantage are disproportionately overrepresented among the most serious of the serious offenders in the cohort (Chung & Steinberg, 2006; Steinberg, Blatt-Eisengart, & Cauffman, 2006). What we do not know, however, is whether these contextual factors predict distinct patterns of offending over time and continued involvement in offending behavior at a high rate over time and across developmental stages.

Knowledge of which individual case characteristics and contextual factors prospectively predict patterns of desistance in serious adolescent offenders and the strength of these effects are valuable for both theoretical and practical reasons. Information about the factors most related to different patterns of involvement in antisocial activities provides leads about the possible mechanisms behind these patterns of behaviors, within the sample as a whole and in identified subgroups (cf. Haviland & Nagin, 2005). On a more practical note, these results provide the empirical base needed to construct structured heuristics or judgment systems for classifying offenders. In short, given the lack of long-term data on serious adolescent offenders generally, and the factors associated with persistence/desistance among such a group specifically (Laub & Sampson, 2001), this study can provide fertile ground for spurring theoretical and policy-relevant discussions about the course, nature, and decisions regarding serious adolescent offending and offenders.

Extending Prior Research

The analyses presented here differ from much of the previous work examining patterns of self-reported offending. First, we study a sample of serious adolescent offenders, rather than a general community or high-risk sample. Because trajectory solutions are groupings of individuals in a sample based on relative patterns of observations over time, any trajectory groups obtained can only be interpreted for their applicability against the backdrop of the sample used for the particular analyses. The trajectories derived here reflect possible subgroups of serious adolescent offenders, not all adolescent offenders or adolescents in general. Second, the time period covered starts with a baseline interview conducted shortly after adjudication and considers observations over the subsequent 3 years; most previous analyses consider changes over different ages, rather than over time. Thus, unlike these prior analyses, the trajectory groups presented here indicate social adaptation in relation to time since adjudication, rather than as a function of chronological age.

Both of these aspects of the design and analysis are deliberate. The Pathways to Desistance Study is primarily concerned with providing data relevant for improving practice and policy in the justice system. As a result, our interest is in the identification of groups of serious adolescent offenders who present the most difficult individual and policy conundrums, who drive policy and legislation well in excess of their numbers in the system, and about whom least is known: those who do not desist from offending, despite having been arrested and convicted of a serious offense (e.g., Laub & Sampson, 2001). In addition, data are examined about the time period directly after court involvement. The pressing question for professionals in the juvenile and adult justice systems is to determine what distinguishes those who get out of the deep end of the system once they are there (Jones, Harris, Fader, & Grubstein, 2001). Looking ahead from a point of court involvement to see what factors might be related to desistance can promote reasoned and informed interventions. A first task in this larger effort is to determine if there are distinct groups of serious adolescent offenders who follow different paths of offending after they are detected by the court, and if there are distinct characteristics of the adolescents who progress along each of these pathways.

Methods

Participants

The pathways study enrolled 1,354 adjudicated adolescents2 who were at least 14 and below 18 years of age at the time of the offense precipitating a court petition to the juvenile or adult court systems in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Phoenix, Arizona, and found guilty (adjudicated) of one of a list of serious offenses. Eligible crimes included all felony offenses with the exception of less serious property crimes, as well as misdemeanor weapons offenses and misdemeanor sexual assault.3 Because drug law violations represent such a significant proportion of the offenses committed by this age group, and because males account for the vast majority of those cases (Stahl, 2003), we were concerned about compromising the heterogeneity of the sample if we did not limit the number of study participants who were drug offenders. Therefore, the proportion of juvenile males with drug offenses was capped at approximately 15% of the sample at each site. All females meeting the age and adjudicated crime requirements and all youths whose cases were being considered for trial in the adult system were eligible for enrollment, even if the charged crime was a drug offense. For most of these adolescents, the most serious adjudicated charge that qualified them for enrollment in the study was a serious crime against person (e.g., armed robbery, felony assault), and this was not their first appearance in court. Further details about the enrollment process and sample characteristics are available in Schubert et al. (2004).

We restricted our current analyses to male adolescent offenders who had at least three completed follow-up interviews out of the possible six (n = 1,119). The ethnicity of this selected sample is 19.6% White, 41.1% African American, 34.7% Hispanic, and 4.6% other. The participants’ average age was 16.0 years (SD = 1.2 years) at the time of the initial interview. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the entire enrolled group, each gender group, and the selected subsample.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Characteristic | Entire Sample | Males | Females | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1,354 | 1,170 | 184 | 1,119 |

| Mean age at study index petition | 16.24 (1.10) | 16.25 (1.11) | 16.16 (1.02) | 16.23 (1.11) |

| Mean number of prior petitionsa | 1.92 (2.14) | 2.06 (2.21) | 1.04 (1.41) | 2.03 (2.20) |

| Mean age at first prior petition | 14.93 (1.64) | 14.85 (1.67) | 15.40 (1.33) | 14.86 (1.66) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian/White | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.20 |

| African American/Black | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.41 |

| Hispanic | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.34 |

| Other | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Most serious offenseb | ||||

| Crime against person | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.45 |

| Property crime | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.27 |

| Drug offense | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 0.13 |

| Weapons offense | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| Other | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Missing data | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

Note: The values in parentheses are standard deviations.

Average count of all prior petitions available in the subject’s court records excluding probation violations.

Most serious charge on study index petition.

There is limited research on longitudinal patterns of female offending (Piquero, Brame, & Moffitt, 2005), but existing studies indicate that patterns and types of female offending over time are likely to differ substantially from male offending (Moretti, Odgers & Jackson, 2004). Unfortunately, we had only a marginally sufficient number of females in the sample (N = 184) to obtain a stable trajectory model for this group alone (cf. Nagin, 2005). Rather than imposing statistical controls for this variable in an overall model, we opted to consider only males in this analysis, a strategy that allows for direct comparisons with existing studies. Analyses of the patterns of female offending in this sample and in others are important directions for future research.

Procedures

Potential participants were identified from a daily review of court record information in each site. Adolescents and their parents (or a participant advocate in situations where parental or guardian contact was unobtainable) provided informed consent to participate in the study, with 20% of those approached (either the adolescent or the parent) declining to participate. Some small, but statistically significant, differences were found between the adolescents who were adjudicated of eligible crimes, but not enrolled, and those adolescents enrolled in the study (these are reported in more detail in Schubert et al., 2004). The enrolled group was younger at their adjudication hearing (15.9 vs. 16.1 years old; t = −4.42, p < .001), had more prior petitions to court (mean of 2.1 vs. 1.5; t = 8.78, p <.001), and appeared in the court for the first time at an earlier age (13.9 vs. 14.2 years old; t =−3.29, p =< .001). We did enroll proportionately more White offenders (test of proportions z = 3.27, p < .005) and fewer African Americans (test of proportions z = 3.09, p < .005), most likely because of the imposition of a cap on the proportion of the sample adjudicated on drug charges. Overall, these data indicate that the enrolled adolescents were no less, and possibly more, serious offenders than those not enrolled.

A baseline interview was conducted within 75 days of adjudication for enrolled youths in the juvenile system and, for those referred to the adult system, within 90 days of their legal certification as adults (as the result of a decertification hearing in Pennsylvania or an adult arraignment hearing in Maricopa County). In most cases (62%), the baseline interview occurred after the disposition hearing. We then conducted a follow-up interview (“time-point” interview) every 6 months for 3 years and then annually thereafter. All study participants have completed at least 3 years of follow-up interviews, but interviews beyond that point are still ongoing. The analyses reported here use data from the baseline interview and the six follow-up interviews completed over the first 3 years after the baseline interview.

The computer-assisted interview assesses status and change across multiple domains such as individual functioning, psychosocial development and attitudes, family and community context, and relationships. A combination of structured and interviewer-rated instruments were used.4 On average, follow-up interviews took 2 hr to complete. Participants were paid for their participation.

Interviews were completed at the participants’ homes, institutional placement, or in a public place such as a library. Attempts were made to provide a private setting or to conduct the interview out of the hearing range of others within each of these locations. Trained interviewers read each item aloud and respondents generally answered aloud. However, in situations or in sections of the interview where privacy was a concern, a portable keypad was provided as an option to obtain a nonverbal response.

Retention of participants in the study was very high during the interval for this analysis. Overall, 3% of participants dropped out of the study and 3% died during the 36-month follow-up period. On average, we completed over 90% of the expected interviews at each time point. As a result, at the 3-year point, 77% of the participants had no missed interviews (they have a baseline and six time-point interviews) and 17% have four or five of the six possible time-point interviews.

Measures

Self-reported offending

We used a modified version of the Self-Report of Offending (SRO; Elliott, 1990; Huizinga, Esbensen, & Weihar, 1991) at each interview to measure the adolescent’s account of his/her involvement in antisocial and illegal activities. The scale used here is composed of 22 items listing different serious illegal activities (the specific items are presented later). The subject indicates whether he/she has done any of these activities “ever” or over the “last 6 months” (both time frames were used at the baseline interview, but only the “last 6 months” time frame was used during each follow-up interview). A sum of the number of items endorsed (a “general variety” score ranging from 0 to 22) is calculated for each subject at each time point.

The SRO measure used in the Pathways to Desistance Study is a version of the most commonly used self-reported delinquency measure across longitudinal studies of antisocial behavior. Repeated analyses have demonstrated the scale’s validity, reliability, association with predictor variables, and correlation with official measures of offending among both general- and offender-based samples in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (see Thornberry & Krohn, 2000). Previous research has shown that a variety score provides a consistent and valid estimate of overall involvement in illegal activity over a given recall period (Osgood, McMorris, & Potenza, 2002; Thornberry & Krohn, 2000).

Two subcategories of the offending variety score are also computed: aggressive offending variety (e.g., “Been in a fight?”) and income offending variety (e.g., “Used checks or credit cards illegally?”). These are calculated in the same manner as the general variety score, except using a limited number of behaviorally homogeneous activities. That is, each of these scores is the sum of the endorsed acts that are either aggressive offenses (for aggressive offending variety score) or income offenses (for income offending variety score). These scores are not used as outcome measures, but are components of a composite score regarding prior offending that is used as a predictor variable in later analyses.

Case characteristics

Demographics

Research participants provided their date of birth, ethnicity, and parental involvement in crime (i.e., whether father was ever arrested or jailed, whether mother was ever arrested or jailed) during the initial interview. Research participants completed the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 1999), which produces an estimate of general intellectual ability (IQ) based on two subtests: one for vocabulary and one for matrix reasoning. The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence performance is correlated with both the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, and it has been normed for individuals aged 6 to 89 years.

Prior history of offending and arrest

Juvenile court records were coded regarding prior involvement with the legal system for criminal offenses. The total number of prior petitions to court and the age at first petition were taken from these official sources. To reduce potential problems from multicollinearity, we constructed a single measure for the construct of antisocial history from multiple indicators (age at first arrest, number of prior petitions in past year, level of self-reported income generating offenses ever, level of self-reported aggressive offenses ever; see Mulvey, Schubert, & Chung, 2007). To derive the composite measure, we performed a confirmatory factor analyses using the full sample of Pathways study subjects, including the variables of age at first petition to court, number of prior court petitions in the past year, SRO aggressive offending variety score (ever), and the SRO income offending variety score (ever). This composite measure fit the data well (comparative fit index [CFI] =0.99; root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.04).

Mood/anxiety and substance use problems were assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), a highly structured clinical interview based on DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnostic criteria (Kessler & Ustün, 2004). The CIDI is a computerized assessment tool administered by nonclinical interviewers (Kessler et al., 2004) that has good concordance with other clinician-based diagnostic instruments (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002). The present study only obtained diagnostic information on major depressive disorder, dysthymia, manic episode, posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol abuse, alcohol dependency, drug abuse, and drug dependency in the previous year. All items were coded as 0 (no diagnosis) or 1 (diagnosis).

Research participants also completed the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (Reynolds & Richmond, 1985), a 37-item, self-report instrument designed to assess the level and nature of anxiety. The subject is asked to endorse or deny each statement as descriptive of his/her feelings or actions. A total anxiety score is computed based on the number of positive endorsements from among 28 items, exclusive of 9 items that comprise a lie subscale (α = 0.87 for the baseline data).

In addition, we assessed the quantity and frequency of alcohol and drug use at the initial interview using items adapted from the Alcohol and Health Study at the University of Missouri (Chassin, Rogosch, & Barrera, 1991; Sher, 1981). This measure considers the adolescent’s use of illegal drugs and alcohol over the course of his/her lifetime and in the past 6 months. The self-report measure is comprised of the following subscales: substance use (e.g., “How often have you had alcohol to drink?”) and social consequences, dependency, and treatment (e.g., “Have you ever had problems or arguments with family or friends before because of your alcohol or drug use?”, “Have you ever wanted a drink or drugs so badly that you could not think of about anything else?”).

In prior work (Mulvey et al., 2007), we developed and reported the psychometric properties of composite scores derived from these measures to indicate the presence or absence of mood/anxiety problems and substance use problems, and we used these same indicators here. Mood/anxiety problems were rated using four dichotomous yes/no variables: (a) past-year diagnosis of major depressive disorder, dysthymia, or a manic episode; (b) past (ever) impairment from depressive symptomatology; (c) past (ever) diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder; and (4) significant anxiety problems. The first three variables were based on items from the CIDI, and the last was based on the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale. The composite for substance use problems was composed of four dichotomous yes/no indicators: (a) past-year diagnosis of alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, or drug dependence; (b) significant lifetime social consequences from alcohol use; (c) significant lifetime social consequences from drug use; and (d) significant dependence symptoms from both alcohol and drug use. The first variable was based on the CIDI interview and the remaining three from the Substance Use/Abuse Inventory. Using items from the Substance Use/Abuse Inventory, we also constructed measures of the amount of substance use over the 6 months prior to the initial interview. Variables reflecting the overall level of alcohol use and the overall substance use frequency were calculated from the self-reports of substance use.

Attitudes toward the legal system

For this study, we developed measures of two central constructs regarding perceptions of the legal process, or legal socialization. Following Sampson and Bartusch (1998), we modified Srole’s (1956) legal anomie scale to create a measure of legal cynicism that assesses general values about the normative basis of law and social norms. The items assess whether laws or rules are not considered binding in the existential, present lives of respondents (Sampson & Bartusch, 1998). Respondents are asked to report their level of agreement with five statements, such as “laws are made to be broken” and “there are no right or wrong ways to make money.” The measure is computed as the mean of the five items, and it fit the baseline data adequately (α = 0.60; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.03).

We also adapted Tyler’s (1990, 1997) measure of legitimacy of law and legal actors. Items measured respondent’s perception of fairness and equity of legal actors in their contacts with citizens, including both police contacts and court processing (Tyler, 1997; Tyler & Huo, 2002; Tyler & Lind, 1992). Respondents indicate their agreement with 11 statements such as “overall, the police are honest,” and “the basic rights of citizens are protected by the courts.” The measure is computed as the mean for the 11 items and this score fit the baseline data adequately (α = 0.80; CFI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.07).

In addition, we used the Mechanisms of Moral Disengagement (Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, 1996) to assess attitudes concerning the treatment of others, a key component of assessing the legitimacy of legal sanctions. The self-report measure contains 32 items that tap a variety of justifications for mistreating others (e.g., “It is alright to beat someone who bad mouths your family.”). Following the recommendations of the authors of the scale, an overall mean of the 32 items was used as a general moral disengagement score. This overall score showed good internal consistency at baseline (α = 0.88).

Psychosocial maturity

Steinberg and Cauffman’s (1996) model of psychosocial maturity consists of three elements: temperance, perspective, and responsibility; each of these has two components. In the present study, we examine each of these six components independently. Specifically, for temperance, we examine impulse control and suppression of aggression; for perspective, we examine consideration of others and future orientation; and for responsibility, we examine personal responsibility and resistance to peer influence. Four measures were used to create these six indices: the Weinberger Adjustment Inventory (WAI; Weinberger & Schwartz, 1990), which includes subscales assessing index impulse control, suppression of aggression, and consideration of others; the Psychosocial Maturity Inventory (Form D; Greenberger, Josselson, Knerr, & Knerr, 1974), which includes a scale that assesses personal responsibility; the Resistance to Peer Influence measure (Steinberg & Monahan, 2007); and the Future Outlook Inventory (Cauffman & Woolard, 1999), which was used to derive a measure of future orientation.

Three subscales of the WAI were used: impulse control (e.g., “I say the first thing that comes into my mind without thinking enough about it”), suppression of aggression (e.g., “People who get me angry better watch out”), and consideration of others (e.g., “Doing things to help other people is more important to me than almost anything else”). The measure asks participants to assess how accurately a series of statements match their own behavior in the previous 6 months (5-point scale, false to true). Each subscale was found to have adequate reliability (as indexed by Cronbach α) and good fit to the baseline data (as indicated by confirmatory factor analysis): impulse control (eight items, α =0.76; normative fit index [NFI] =0.95; CFI =0.95; RMSEA = 0.07), suppression of aggression (seven items, α = 0.78; NFI = 0.96; CFI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.06), and consideration of others (seven items, α = 0.73; NFI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.04).

The Future Outlook Inventory is a 15-item measure that utilizes items from the Life Orientation Task (Scheier & Carver, 1985), the Zimbardo Time Perspective Scale (Zimbardo, 1990), and the Consideration of Future Consequences Scale (Strathman, Gleicher, Boninger, & Edwards, 1994). The inventory asks participants to rank the degree to which each statement reflects how they usually act, on a scale of 1 (never true) to 4 (always true). A future orientation score is calculated based on the mean of eight items from the scale (e.g., “I will keep working at difficult, boring tasks if I know they will help me get ahead later”). The scale showed good reliability and an excellent fit to the baseline data (α = 0.68; NFI = 0.96; CFI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.03).

The Psychosocial Maturity Inventory includes a 30-item subscale that assesses personal responsibility (e.g., “If something more interesting comes along, I will usually stop any work I’m doing,” reverse scored). Individuals respond on a 4-point scale, from strongly disagree to strongly agree; an overall personal responsibility score is calculated as the mean across all 30 items. The measure showed excellent reliability and an adequate fit to the baseline data (α =0.89; NFI =0.82, CFI =0.87, and RMSEA = 0.04).

The measure of resistance to peer influence (Steinberg & Monahan, 2007) assesses the degree to which adolescents act autonomously in interactions with their peer group. Participants are first presented with two conflicting statements (e.g., “Some people go along with their friends just to keep their friends happy” and “Other people refuse to go along with what their friends want to do, even though they know it will make their friends unhappy”) and are then asked to choose the characterization that most closely reflects their behavior. Next, the participant is asked to rate the degree to which the statement is accurate (i.e., “sort of true” or “really true”). Each item is then scored on a 4-point scale, ranging from really true for the characterization indicating less resistance to influence (1) to really true for the characterization indicating more resistance to influence (4), with answers of sort of true assigned a score of 2 (if associated with the less resistant option) or 3 (if associated with the more resistant option). Ten such items are presented to the participant, each exploring a different dimension of peer influence (e.g., going along with friends, saying things one does not really believe), and one resistance to peer influence score is computed for this measure by averaging scores on the 10 items. The measure showed excellent reliability and adequate fit to the baseline data (α =0.73; NFI = 0.92; CFI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.04).

Three composite measures (used in previous research, see Cauffman & Steinberg, 2000) were constructed from these instruments. A temperance scale is computed as the standardized mean of the 15 items comprising the impulse control and suppression of aggression subscales of the WAI. A perspective scale is computed as the mean of the standardized Future Outlook Inventory score and the “consideration of others” subscale from the WAI. A responsibility scale is computed as the mean of the standardized Psychosocial Maturity Inventory score and the standardized resistance to peer influence score.

Table 2 summarizes the composite measures of individual characteristics that were used in these analyses. Composite measures were used to represent prior criminal behavior, mood/anxiety problems, substance use problems, and aspects of psychosocial maturity (temperance, perspective, and responsibility). These composites all fit the data well and represent constructs of interest in a parsimonious manner.

Table 2.

Composite measures of constructs

| Construct | Indicators | Instrument |

|---|---|---|

| Prior criminal behavior | Age at first arrest | Court record |

| Number of prior court petitions (past year) | Court record | |

| Aggressive offenses | Self-report offending | |

| Income offenses | Self-report offending | |

| Mood/anxiety problems | Diagnosis of select mood disorder (past year) | CIDI |

| Impairment from depressive symptoms (ever) | CIDI | |

| Diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (ever) | CIDI | |

| Significant anxiety problems | Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale | |

| Substance use problems | Diagnosis of substance use disorder | CIDI |

| Significant social consequences from alcohol use | Substance use/abuse inventory | |

| Significant social consequences from drug use | Substance use/abuse inventory | |

| Dependence symptoms from alcohol or drug use | Substance use/abuse inventory | |

| Temperance | Impulse control | WAI |

| Suppression of aggression | WAI | |

| Perspective | Future outlook score | Future Outlook Inventory |

| Consideration of others | WAI | |

| Responsibility | Psychosocial maturity | Psychosocial Maturity Index |

| Resistance to peers | Resistance to peer influence |

Note: CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; WAI, Weinberger Adjustment Inventory.

Social contextual characteristics

Neighborhood disadvantage

We created a summary score of the adolescent’s neighborhood resources based on census data for each of the locales (c.f., Chung & Steinberg, 2006). “Neighborhood” was defined by 2000 census tract boundaries and based on the address youth identified as their primary residence at the time of the baseline interview. The measure of neighborhood disadvantage was derived using four indicators from 2000 Census data: percentage of households below the poverty line; percentage of households receiving public assistance; percentage of unemployed residents; and percentage of residents with less than a high school education (US Bureau of the Census, 2000). These factors are robust predictors of neighborhood risk that are associated with elevated rates of both juvenile and adult crime (for a review, see Fagan, 2008). A principal components analysis, run separately for Philadelphia and Maricopa County, revealed one factor that accounted for 79% and 77%, respectively, of total explained variance. Factor scores for neighborhood disadvantage were used in the main analyses.

Parenting

The Parental Monitoring Inventory (Steinberg, Lamborn, Dornbusch, & Darling, 1992) was adapted for this study to assess parenting practices related to supervision of the adolescent. Preliminary questions establish the presence of a single individual who is primarily responsible for the youth. The respondent’s answers to several items about their current living situation, specifically whether they live with the identified caretaker, establishes the skip pattern followed in the parental monitoring items. The scale is composed of nine items. Five items assess parental knowledge, and are asked even if a youth does not live with the person identified as their primary caretaker. If the youth lives with the primary caretaker, four additional items are asked to assess parental monitoring of the youth’s behavior (e.g., “How often do you have a set time to be home on weekend nights?”). A parental knowledge score is calculated as the mean of the five items regarding parental knowledge and a parental monitoring score is calculated as the mean of the four items addressing this aspect of the relationship. Confirmatory factor analyses were conducted fitting a two-factor solution with the above subscale scores to the baseline data. This solution, allowing for one correlated error term fit the data well (CFI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.08).

The Quality of Parental Relationships Inventory (Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, & Simons, 1994) was adapted for this study to assess the affective tone of the parental–adolescent relationship, asked separately with regard to mother and father. Forty-two items tap parental warmth (e.g., “How often does your mother let you know she really cares about you?”). For this study, we used the scale for the parental warmth of the mother, which showed reasonably acceptable fit to the baseline data (α =0.92; NFI =0.95; CFI =0.95; RMSEA =0.08). There were too many missing values for the ratings of the parental warmth of the father to include this variable.

Peers

The Peer Delinquent Behavior items are a subset of 19 questions used by the Rochester Youth Study (Thornberry, Lizotte, Krohn, Farnworth, & Jang, 1994) to assess the degree of antisocial activity among the adolescent’s peers. Research participants answer questions about the level of involvement of their friends in illegal activities (e.g., “How many of your friends have sold drugs?”) and the amount of pressure that their friends exert on them to be involved in illegal activities (e.g., “How many of your friends have suggested that you should sell drugs?”). Two scores are derived from this measure. The peer delinquency–behavior score is the mean of the 12 items regarding the involvement of peers in illegal activity. The peer delinquency–influence score is the mean of the 7 items regarding whether peers pressure the adolescent to engage in illegal activities. Confirmatory factor analyses for each of these scales showed good fits to the baseline data (peer delinquency–behavior: α = 0.92; NFI = 0.93; CFI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.09; peer delinquency–influence: α = 0.89; NFI = 0.95; CFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.07).

Results

Latent class growth analysis was used to identify groups that follow distinctive patterns or pathways of self-reported antisocial behavior over time. Latent class growth analysis uses a single outcome variable measured at multiple time points to define a latent class model in which the latent classes correspond to different growth curve shapes for the outcome variable. The analysis estimates the different growth curve shapes and class probabilities for each group (Muthén & Muthén, 2000). We used the group-based trajectory modeling procedure developed by Nagin and colleagues (Land, McCall, & Nagin, 1996; Land & Nagin, 1996; Nagin, 2005; Nagin & Land, 1993; Nagin & Tremblay, 1999; Roeder, Lynch, & Nagin, 1999) to identify subgroups of individuals who display similar patterns of behavior over time. Analyses were done using the PROC TRAJ program, an SAS procedure for estimating group-based trajectory models. Because we were analyzing count data (number of acts endorsed) and more zeros were present than would be expected in the purely Poisson model, we used the zero-inflated Poisson model (Lambert, 1992; Zorn, 1998). Because we were not testing nested models, we followed the lead of D’Unger, Land, McCall, and Nagin (1998) and used the change in the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) to compare the fit of different models, according to the guidelines provided by Jones, Nagin, and Roeder (2001).

The level of missing data for the self-report measure was low. The total number of interviews completed on the sample (N = 6,365) represents 95% of the number of interviews that could have possibly been collected if all subjects (N = 1,119) were successfully interviewed at each time point. Only 10 completed interviews had missing data on self-reported antisocial activity. Missing data were assumed to be missing at random in the PROC TRAJ program.

The analysis examining the sample for trajectory groups took into account the effect of institutional confinement on the subject’s level of offending, because this factor can substantially affect the derived solution in samples of active offenders (see Piquero et al., 2001). Exposure time or the amount of time the subject was free to engage in criminal acts in the community was used as a time-varying covariate in the analysis. This value was a proportion indicating the total days during the 6-month recall period that the individual was reported to be in the community (i.e., not in a detox/drug treatment facility, psychiatric hospital, secure facility, or residential treatment facility). This information was not available for the baseline observation, so these values were set uniformly to 1 for this starting period (Nagin, 2005).

Patterns of self-reported offending and identification of subgroups

Mixtures of up to seven latent classes were considered. At the initial stage where we decided on the number of classes, the form of the polynomial used to capture the shape of each trajectory group was cubic in time. Table 3 presents the values of BIC and 2loge(B10) for the solutions with different number of groups.

Table 3.

BIC and 2loge(B10) of the models considered

| No. of Groups | BIC | Null Model | 2loge(B10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −14586.20 | ||

| 2 | −13008.40 | 1 | 3155.6 |

| 3 | −12641.75 | 2 | 733.3 |

| 4 | −12522.83 | 3 | 237.8 |

| 5 | −12461.63 | 4 | 122.4 |

| 6 | −12417.87 | 5 | 87.52 |

| 7 | −12390.26 | 6 | 55.22 |

Note: BIC, Bayesian information criterion; 2loge(B10), twice the logarithm of the Bayes factor. The null model column represents the number of groups tested in the null hypothesis. Here, 2loge(B10) ≈ 2(ΔBIC), where ΔBIC is the BIC of the alternative (more complex) model minus the BIC of the null (simpler) model. The log form of the Bayes factor is interpreted as the degree of evidence favoring the alternative model.

For these data the BIC continued to improve as more groups were added, which is typical. The five-group trajectory solution was chosen as the overall best fitting model, however, because the six- and seven-group trajectory solutions did not add substantially to the understanding of different group patterns. The additional subgroups identified in these solutions were small (<5% of the sample) and did not indicate trajectories that were distinct in shape from the ones appearing in the five-group solution.

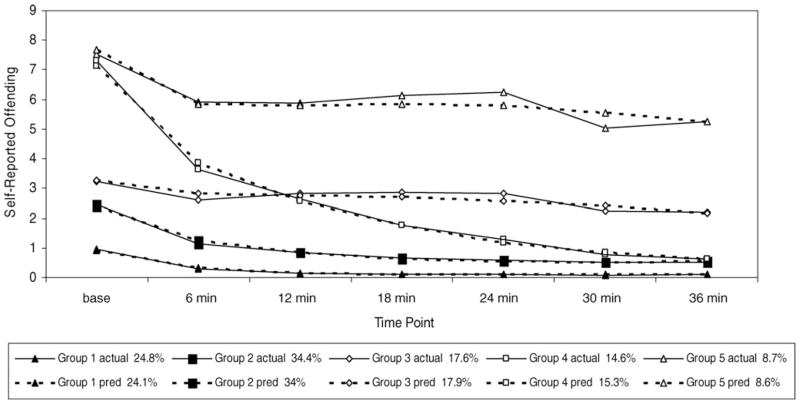

Figure 1 shows the final, five-group trajectory solution using exposure time as a time-varying covariate. Group 1, which comprises about 24.8% of the sample, is a low offending group, with a low level of offending at baseline that approaches zero in the follow-up periods. Group 2, which makes up about 34.4% of the sample, is also a low offending group but with a slightly more marked decline than group 1 in the first two follow-up periods. Group 3, which constitutes 17.6% of the sample, has moderate levels of offending across the 36-month period. Group 4, which represents about 14.65% of the sample, is a high declining group whose level of offending is relatively high at the start and steadily decreases across the 36-month period (i.e., “desisters”). Group 5, which forms about 8.7% of the sample, is a high offending group whose level of offending is high at the start and remains relatively higher compared to other groups across the 36-month period (i.e., “persisters”). Comparisons of these two groups may be especially informative to our understanding of the desistance process.

Figure 1.

The five-group trajectory solution for males controlling for exposure time using the zero-inflated Poisson model.

We checked the appropriateness of this five-group model, using four diagnostic standards recommended by Nagin (2005): (a) the average posterior probability of group membership should be at least 0.7 for all the groups, (b) the odds of correct classification is greater than 5 for all groups, (c) there is a reasonably close correspondence between a group’s estimated probability of membership and the proportion of individuals classified to the group on the basis of maximum posterior probability assignment rule, and (d) the confidence interval for group membership probability is sufficiently narrow. Table 4 presents the four diagnostics of model performance in the sample and suggests that the capacity of the model to estimate group membership probabilities and to sort cases among the groups is very good. For each group, there is a close correspondence between the estimated probability of membership and the proportion assigned to the group on the basis of a maximum posterior assignment probability rule. The 95% confidence intervals are also relatively narrow for each group, less than 0.06 plus or minus π̂j. The average posterior probability of group membership is considerably above the 0.7 cutoff for each group, and the odds of correct classification is also considerably above 5 for all the groups.

Table 4.

Diagnostics of model performance

| Group j | π̂j | pj | AVPPj | OCCj | 95% CI for πj |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.241 | 0.247 | 0.84 | 16.53 | (0.18, 0.30) |

| 2 | 0.340 | 0.344 | 0.82 | 8.84 | (0.29, 0.39) |

| 3 | 0.179 | 0.176 | 0.84 | 24.08 | (0.15, 0.21) |

| 4 | 0.153 | 0.145 | 0.83 | 27.03 | (0.12, 0.19) |

| 5 | 0.086 | 0.086 | 0.91 | 107.46 | (0.07, 0.11) |

Note: π̂j, estimated probability of group membership; pj, proportion of the sample classified in group j; AVPPj, average posterior probability of classification in group j; OCCj, odds of correct classification in group j, where OCCj = [AVPPj/(1 − AVPPj)]/[π̂j/(1 − π̂j)]; CI, confidence interval.

An illustrative figure shows the differences in the levels of self-reported antisocial activity among the groups. Figure 2 shows the proportion of each of three of the groups at different levels of self-reported offending (Groups 1, 3, and 5) that endorses each of the items included in the SRO variety score at the initial interview. Given the much larger percentages of endorsement across all items, it is clear that the high offending group (Group 5) is reporting a level and range of criminal activity that is many times that reported by members of the low offending groups.

Figure 2.

The proportion of Groups 1, 3, and 5 reporting activity for the past 6 months at the initial interview.

Across the whole sample, the types of offenses reported at each time point roughly mirrors the patterns of endorsement seen at baseline. Although there is a general decline in the proportion of the sample reporting involvement over the recall period, there is consistency in which items are endorsed most at each time point. The most frequently reported behaviors and their ranges of prevalence rates for endorsement over the follow-up time points are fighting (23.1–43.9%), buying/selling stolen goods (8.8–17.2%), destroying property (6.7–14.6%), driving drunk (11.4–13.5%), selling marijuana (9.5–12%), carrying a gun (8.7–12%), strong arm robbery (4.1–11.3%) and selling other drugs (8.3–10.6%). Other offenses were endorsed by less than 10% of the adolescents at any given time point. These results indicate a general involvement across a variety of offenses among these serious adolescent offenders.

Exposure time had a significant effect on each trajectory group. Entered as a time-varying covariate for each recall period, the amount of time in the community had a significant positive effect (p < .05) across all time periods on the offending rates of Groups 2, 3, 4, and 5. This indicates that more time spent in the community was related to a higher rate of offending for the adolescents belonging to these groups. In the low offending group (Group 1), however, exposure time had a significant negative effect on the rate of offending. This indicates that for this group more time in the community was associated with lower rates of offending and more time in institutional care was related to higher rates of offending.

It is difficult to cleanly interpret the strength of this effect in terms of increased offending in this low offending group. The use of a zero-inflated Poisson model means that the effect is not uniform across each time point, and that the size of the effect is related to a reduction in the log rate of offending at each time point (B. Jones, personal communication, March 26, 2009). Estimates of the effect at each time point (available from the author upon request) indicate that the overall impact on offending is statistically significant but rather small. The rate of offending is estimated to increase by less than by 7% of this already very low rate with each 10% increase in the proportion of time spent in institutional care.

It is important to know the average number of months each group spent in institutional care during the follow-up period and the types of institutions experienced in order to interpret this effect. Figure 3 presents the proportion of time spent in institutional care during the 3-year period for each group. The difference among the groups is significant (F = 12.07, p < .001), with the lower offending groups spending less time in institutional care. It is worth noting that even the group reporting the lowest levels of offending (Group 1) spent almost a third of the follow-up period in an institutional setting. There is, however, no significant difference between Groups 4 and 5 in the amount of time spent in institutional care.

Figure 3.

The proportion of the follow-up period spent in institutional care for each trajectory group. The error bars represent a 95% confidence interval.

The types of facilities where adolescents spent time over the recall period were also examined. Each institution was classified as being one of nine possible types of facilities: (a) drug or alcohol treatment unit, (b) psychiatric hospital or psychiatric unit of a general hospital, (c) shelter, (d) jail or prison, (e) juvenile detention center, (f) state training school, (g) contracted residential treatment with a mental health focus, (h) contracted residential treatment center with a general focus, and (i) other. Detailed definitions for each of these types of settings and the types of services provided to this sample during institutional stays are provided in Mulvey et al. (2007). Those authors found that, during the first 2 years of follow-up, the most commonly reported institutional stays were those in jails/prisons, contracted residential settings with a general focus, juvenile detention centers, and state training schools. When Groups 4 and 5 are examined separately for the current analyses, they also report staying in these four types of facilities. There is, however, no significant difference across the recall period in the proportion of Groups 4 and 5 who spend some time in these different types of facilities (i.e., approximately 41% across both groups report a stay in a jail or prison, approximately 15% a stay in juvenile detention, approximately 14% a stay in a contracted residential facility, and approximately 10% a stay in a state training school). It appears that the adolescents in Groups 4 and 5 are likely to be placed in secure institutions, but that individuals in these two groups spent equivalent amounts of time in institutional care and are equally likely to spend time in the same types of facilities over the follow-up period.

Differentiating trajectory group membership

We next conducted a series of analyses to identify factors that distinguish membership in the trajectory subgroups identified above. We first examined which variables differentiated the five identified subgroups. We then looked at which factors differentiate Groups 4 and 5. These latter analyses provide more focused information on what characteristics might distinguish adolescents who start and stay at a high rate of offending from those who start at a comparably high rate and then move to a near zero rate over the follow-up period. The levels of missing data on individual variables were low (the highest being 12% for parental monitoring, with all others below 6%), and the full information at maximum likelihood procedure was used to replace missing values.

Table 5 presents the correlation matrix of the individual and social context variables. Inspection of these correlations indicates few problems with multicollinearity among these variables. Only 4 of the 231 correlation coefficients exceed .50: peer influence and peer behavior at .703, alcohol use and the frequency of substance use at .698, substance use problems composite score and frequency of substance use at .549, and peer delinquency–antisocial behavior and composite score for antisocial history at .528. Prior analyses with these data have not produced acceptable factor solutions that combined these variables. Moreover, the variables with notably high intercorrelations are indicators of similar constructs, possibly reducing the efficiency of the model tested, but not seriously affecting the interpretability of the findings.

Table 5.

Correlation matrix (Pearson correlation coefficients) of case characteristic and social contextual variables

| Age at Baseline |

Biological Father Arrested/Jailed |

Biological Mother Arrested/Jailed |

Full Scale IQ | Antisocial History Composite Score |

Substance Use Problem Composite |

Mood/Anxiety Composite Score |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline | |||||||

| Biological father arrested or jailed | −0.062 | ||||||

| Biological mother arrested or jailed | −0.025 | 0.168 | |||||

| Full scale IQ WASI | 0.006 | 0.072 | 0.022 | ||||

| Antisocial history composite score | −0.031 | 0.172 | 0.133 | 0.048 | |||

| Substance use problem composite | 0.165 | 0.103 | 0.107 | 0.118 | 0.480 | ||

| Mood/anxiety composite score | 0.055 | 0.061 | 0.048 | 0.020 | 0.138 | 0.200 | |

| Legal cynicism | 0.034 | 0.050 | 0.046 | −0.065 | 0.188 | 0.169 | 0.023 |

| Legitimacy of law | −0.145 | −0.037 | −0.022 | 0.061 | −0.184 | −0.069 | −0.079 |

| Moral disengagement | −0.001 | 0.028 | 0.042 | −0.009 | 0.307 | 0.324 | 0.073 |

| Temperance Scale | −0.001 | −0.105 | −0092 | −0.004 | −0.393 | −0.402 | −0.170 |

| Responsibility Scale | 0.080 | −0.023 | −0.029 | 0.156 | −0.070 | −0.123 | −0.086 |

| Perspective Scale | 0.059 | −0.107 | −0.057 | −0.069 | −0.220 | −0.176 | 0.034 |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | −0.039 | 0.037 | 0.015 | −0.235 | 0.051 | −0.059 | −0.006 |

| Parental monitoring | −0.263 | −0.055 | −0.048 | −0.006 | −0.218 | −0.223 | −0.034 |

| Parental knowledge | −0.139 | −0.082 | −0.067 | −0.012 | −0.262 | −0.304 | −0.054 |

| Parental warmth–mother | −0.059 | −0.046 | −0.049 | −0.129 | −0.013 | −0.082 | −0.061 |

| Peer delinquency–antisocial behavior | 0.109 | 0.119 | 0.065 | 0.048 | 0.528 | 0.469 | 0.139 |

| Peer delinquency–antisocial influence | 0.119 | 0.090 | 0.047 | 0.079 | 0.403 | 0.471 | 0.139 |

| Alcohol use | 0.130 | 0.026 | 0.048 | 0.126 | 0.337 | 0.439 | 0.081 |

| Frequency of substance use | 0.104 | 0.081 | 0.075 | 0.134 | 0.413 | 0.549 | 0.126 |

| Being White | −0.058 | 0.045 | 0.041 | 0.271 | −0.010 | 0.092 | 0.014 |

| Being Latino | −0.027 | −0.026 | 0.041 | −0.034 | 0.076 | 0.124 | −0.013 |

| Legal Cynicism | Legitimacy of Law | Moral Disengagement | Temperance Scale | Responsibility Scale | Perspective Scale | Neighborhood Disadvantage | |

| Age at baseline | |||||||

| Biological father arrested or jailed | |||||||

| Biological mother arrested or jailed | |||||||

| Full scale IQ WASI | |||||||

| Antisocial history composite score | |||||||

| Substance use problem composite | |||||||

| Mood/anxiety composite score | |||||||

| Legal cynicism | |||||||

| Legitimacy of law | −0.157 | ||||||

| Moral disengagement | 0.441 | −0.162 | |||||

| Temperance Scale | −0.296 | 0.123 | −0.476 | ||||

| Responsibility Scale | −0.183 | −0.112 | −0.296 | 0.289 | |||

| Perspective Scale | −0.195 | 0.139 | −0.220 | 0.246 | 0.135 | ||

| Neighborhood disadvantage | 0.089 | −0.006 | 0.069 | −0.020 | −0.094 | 0.013 | |

| Parental monitoring | −0.170 | 0.173 | −0.182 | 0.143 | −0.015 | 0.189 | −0.065 |

| Parental knowledge | −0.133 | 0.167 | −0.212 | 0.189 | 0.063 | 0.220 | 0.017 |

| Parental warmth–mother | −0.117 | 0.029 | −0.141 | 0.140 | 0.150 | 0.258 | 0.104 |

| Peer delinquency–antisocial behavior | 0.223 | −0.173 | 0.377 | −0.410 | −0.100 | −0.190 | 0.107 |

| Peer delinquency–antisocial influence | 0.189 | −0.075 | 0.341 | −0.404 | −0.206 | −0.160 | 0.064 |

| Alcohol use | 0.118 | −0.060 | 0.218 | −0.260 | −0.075 | −0.179 | −0.040 |

| Frequency of substance use | 0.180 | −0.092 | 0.272 | −0.318 | −0.048 | −0.208 | −0.051 |

| Being White | −0.060 | 0.097 | −0.028 | −0.075 | 0.019 | −0.086 | −0.368 |

| Being Latino | 0.090 | 0.141 | 0.122 | −0.064 | −0.243 | −0.069 | 0.280 |

| Parental Monitoring | Parental Knowledge | Parent Warmth–Mother | Peer Delinquency–Antisocial Behavior | Peer Delinquency–Antisocial Influence | Alcohol Use | Frequency of Substance Use | |

| Age at baseline | |||||||

| Biological father arrested or jailed | |||||||

| Biological mother arrested or jailed | |||||||

| Full scale IQ WASI | |||||||

| Antisocial history composite score | |||||||

| Substance use problem composite | |||||||

| Mood/anxiety composite score | |||||||

| Legal cynicism | |||||||

| Legitimacy of law | |||||||

| Moral disengagement | |||||||

| Temperance Scale | |||||||

| Responsibility Scale | |||||||

| Perspective Scale | |||||||

| Neighborhood disadvantage | |||||||

| Parental monitoring | |||||||

| Parental knowledge | 0.359 | ||||||

| Parental warmth–mother | 0.158 | 0.167 | |||||

| Peer delinquency–antisocial behavior | −0.233 | −0.282 | −0.007 | ||||

| Peer delinquency–antisocial influence | −0.184 | −0.198 | −0.077 | 0.703 | |||

| Alcohol use | −0.204 | −0.175 | −0.049 | 0.374 | 0.376 | ||

| Frequency of substance use | −0.195 | −0.246 | −0.033 | 0.417 | 0.378 | 0.698 | |

| Being White | 0.096 | 0.036 | −0.111 | −0.102 | −0.029 | 0.054 | 0.148 |

| Being Latino | −0.028 | 0.005 | −0.014 | 0.127 | 0.106 | 0.178 | 0.090 |

Note: WASI, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence.

Diagnostic statistics show no marked problems with multicollinearity among these variables. On the full sample, the variance inflation factors for the variables range between 1.1 (biological mother arrested or jailed) and 2.5 (peer delinquency–antisocial behavior). For the sample of cases in trajectory Groups 4 and 5, the variance inflation factors range from 1.1 (mood/anxiety composite score) to 2.5 (frequency of substance use). These values are below the standard criteria of 10 or the more stringent criteria of 2.5 for binary logistic models with smaller samples (Allison, 1999).

A multinomial logistic regression, entering all variables simultaneously, was performed to assess the relative associations of the case characteristics with trajectory group membership. The overall model was statistically significant and explained group variability reasonably well, χ2 (92) = 705.39; Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 = .509; p < .001. Table 6 presents the overall results of this analysis. Variables across several domains differentiated among the five groups; demographics (age, ethnicity), historical factors (antisocial history factor score, whether father has an arrest record), contextual influences (level of peer antisocial behaviors), behavioral indicators (level of substance use in the 6 months before the initial interview), and psychosocial variables (temperance and perspective scores) were all significant contributors to the overall model.

Table 6.

Overall main effects for multinomial logistic regression of trajectory group membership on case characteristics and social context variables

| Effect | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 12.74 | <.013* |

| Ethnicity | 16.45 | <.036* |

| Father arrested/jailed | 15.13 | <.004* |

| Mother arrested/jailed | 3.93 | <.416 |

| IQ | 3.64 | <.457 |

| Antisocial history | 53.33 | <.001* |

| Substance use problem | 2.81 | <.591 |

| Mood/anxiety problem | 3.98 | <.409 |

| Legal cynicism | 2.00 | <.736 |

| Legitimacy | 7.79 | <.100 |

| Moral disengagement | 0.50 | <.973 |

| Temperance | 18.32 | <.001* |

| Responsibility | 4.74 | <.316 |

| Perspective | 17.97 | <.001* |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | 3.57 | <.468 |

| Parental | ||

| Monitoring | 7.71 | <.103 |

| Knowledge | 3.22 | <.523 |

| Warmth | 4.29 | <.368 |

| Peers | ||

| Behavior | 54.48 | <.001* |

| Attitudes | 5.84 | <.212 |

| Level of alcohol use | 5.02 | <.286 |

| Frequency of substance use | 34.77 | <.001* |

Note: The chi-square values are computed as −2(LUR – LR) ~χ2, where LUR and LR are the maximized log-likelihoods of the full and restricted models, respectively. All tests have 4 degrees of freedom.

p ≤ .05.

A summary of the significant results (ps < .05) of the post hoc tests for group differences is presented in Table 7. The post hoc tests for this solution indicated that several case characteristics consistently distinguished among certain trajectory groups. Age was significantly different between Groups 1 and 3, 2 and 3, 3 and 4, and 3 and 5. Group 3 was somewhat younger than the other groups (mean ages in years: Group 1 =16.03, Group 2 = 16.06, Group 3 = 15.87, Group 4 = 16.12, Group 5 = 16.04). Other variables consistently distinguished the highest and lowest offending groups. Having a father with an arrest or jail history distinguished Group 5 (the persisters) from every other group, and also distinguished between Groups 1 and 2 (both low level offending groups). (The proportion of each group with a father with a history of being arrested or jailed is as follows: Group 1 =22%, Group 2 =36%, Group 3 =41%, Group 4 = 35%, Group 5 = 58%.) Two of the psychosocial maturity variables (temperance and perspective) differentiated the lowest offending group (Group 1) from every other group (except for Group 3, where only temperance was significant). The psychosocial maturity variable of “perspective” was also significantly different between Group 5 (the persisters) and each other group. Finally, two variables appeared to distinguish almost all of the groups from each other. There were significant differences in the level of peer antisocial behavior between every pair of groups except Groups 4 and 5. The total substance use score was also significantly different in all the group comparisons except the ones between Groups 2 and 3 and Groups 4 and 5.

Table 7.

Significant effects of post hoc analyses of group differences

| Group Ref. vs. Other | Variable | β | Wald | Exp(β) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 vs. 1 | Father arrested/jailed | 0.51 | 6.14 | 1.66 | <.013 |

| Antisocial history | −0.83 | 16.63 | −0.44 | <.001 | |

| Temperance | 0.29 | 7.62 | 1.33 | <.006 | |

| Perspective | 0.27 | 5.21 | 1.31 | <.023 | |

| Peers–behavior | −0.58 | 10.77 | 0.56 | <.001 | |

| Frequency of substance use | −0.08 | 7.76 | 0.93 | <.005 | |

| 3 vs. 1 | Age | 0.30 | 8.36 | 1.35 | <.004 |

| Antisocial history | −1.05 | 19.35 | 0.35 | <.001 | |

| Temperance | 0.48 | 12.84 | 1.62 | <.001 | |

| Peers–behavior | −0.98 | 22.48 | 0.37 | <.001 | |

| Ethnicity (being minority) | −0.82 | 5.32 | 0.44 | <.021 | |

| Frequency of substance use | −0.06 | 4.05 | 0.946 | <.044 | |

| 3 vs. 2 | Age | 0.29 | 10.25 | 1.34 | <.001 |

| Legitimacy | 0.36 | 4.26 | 1.44 | <.039 | |

| Peers–behavior | −0.40 | 6.27 | 0.67 | <.012 | |

| Ethnicity (being minority) | −0.86 | 8.25 | 0.43 | <.004 | |

| 4 vs. 1 | Antisocial history | −1.71 | 41.97 | 0.18 | <.001 |

| Parental monitoring | −0.43 | 5.57 | 0.65 | <.018 | |

| Temperance | 0.36 | 5.44 | 1.44 | <.020 | |

| Perspective | 0.43 | 6.20 | 1.53 | <.013 | |

| Peers–behavior | −1.39 | 37.54 | 0.25 | <.001 | |

| Frequency of substance use | −0.14 | 22.86 | 0.87 | <.001 | |

| 4 vs. 2 | Antisocial history | −0.89 | 17.44 | 0.41 | <.001 |

| Legitimacy | 0.47 | 4.96 | 1.60 | <.026 | |

| Peers–behavior | −0.81 | 20.19 | 0.45 | <.001 | |

| Frequency of substance use | −0.07 | 13.52 | 0.94 | <.001 | |

| 4 vs. 3 | Age | −0.27 | 5.77 | 0.76 | <.016 |

| Antisocial history | −0.66 | 8.84 | 0.52 | <.003 | |

| Parental monitoring | −0.38 | 5.20 | 0.68 | <.023 | |

| Peers–behavior | −0.40 | 4.38 | 0.67 | <.036 | |

| Ethnicity (being minority) | 0.90 | 5.84 | 2.46 | <.016 | |

| Level of alcohol use | 0.12 | 4.27 | 1.13 | <.039 | |

| Frequency of substance use | −0.08 | 17.60 | 0.92 | <.001 | |

| 5 vs. 1 | Father arrested/jailed | 1.07 | 11.53 | 2.94 | <.001 |

| Antisocial history | −1.85 | 35.06 | 0.16 | <.001 | |

| Temperance | 0.69 | 11.98 | 2.00 | <.001 | |

| Perspective | 0.84 | 15.65 | 2.31 | <.001 | |

| Peers–behavior | −1.63 | 34.65 | 0.20 | <.001 | |

| Peers–attitudes | 0.58 | 5.16 | 1.78 | <.023 | |

| Frequency of substance use | −0.12 | 13.60 | 0.89 | <.001 | |

| 5 vs. 2 | Father arrested/jailed | 0.58 | 4.39 | 1.79 | <.036 |

| Antisocial history | −1.02 | 14.57 | 0.36 | <.001 | |

| Temperance | 0.40 | 4.79 | 1.50 | <.029 | |

| Perspective | 0.57 | 8.66 | 1.76 | <.003 | |

| Peers–behavior | −1.05 | 19.34 | 0.35 | <.001 | |

| Ethnicity (being minority) | −0.85 | 4.26 | 0.43 | <.039 | |

| Frequency of substance use | −0.04 | 3.92 | 0.96 | <.048 | |

| 5 vs. 3 | Age | −0.29 | 3.93 | 0.75 | <.048 |

| Father arrested/jailed | 0.69 | 5.53 | 2.00 | <.019 | |

| Antisocial history | −0.80 | 8.63 | 0.45 | <.003 | |

| Perspective | 0.65 | 10.91 | 1.92 | <.001 | |

| Peers–behavior | −0.65 | 7.00 | 0.52 | <.008 | |

| Frequency of substance use | −0.06 | 6.85 | 0.94 | <.009 | |

| 5 vs. 4 | Perspective | 0.41 | 4.54 | 1.51 | <.033 |