Abstract

The purpose of this study was to illuminate the experiences of poor, urban HIV-positive drug users. Sixty participants were asked about HIV risk behaviors, the impact of HIV on their lives, religious beliefs, life plans, relationships, and work-related issues both prior to and since diagnosis. A theoretical framework was developed using Frank's (1995; 1998) Illness Narratives and Boss and Couden's (2002) Ambiguous Loss theories. Themes pertaining to both physical and emotional or spiritual dimensions were located within Benefit, Loss, or Status Quo orientations. The findings contribute to researchers' understanding of the HIV/AIDS illness experiences among the very marginalized and they have important implications for physical and mental health care professionals working with HIV-positive drug users.

Increasingly, public health responses to the AIDS epidemic are shifting to the treatment and care end of the treatment/prevention continuum. The movement of both public and private intervention resources toward the provision of care, treatment, and secondary rather than primary prevention for people living with HIV/AIDS underscores the importance of developing a better understanding of illness experiences in this population. How people respond to treatment and even their symptoms has been shown to be impacted by how illness is conceptualized and experienced by the sufferer (Troop, et al., 1997). Consequently, assessment of HIV/AIDS illness experiences emerges as a critical element in the process of helping people living with the disease to embrace understandings that contribute to better health and emotional outcomes.

HIV/AIDS is a unique illness in that the trajectory from health into illness is generally not linear. Some people live with the disease for an extended period of time with relatively few obvious signs or symptoms. Others become incapacitated in a relatively short period of time. Still others confound expectations by overcoming severe illness, high viral loads, and low t-cell counts by eventually returning to a state of relative health in which there is little evidence of HIV in their systems. Transposed upon the HIV-positive individual's experience are the changes and advances in medical knowledge about the disease, including improved medical care and drug therapy for those who are connected to the health care system and can afford to be involved in such expensive and complex regimens. Another layer involves the relationships between those infected and important others, including health care workers, family, and friends, who may in turn communicate stigma, rejection, and advocacy.

Poor, urban drug users with HIV face even greater challenges along several fronts. For example, many are intermittently or chronically homeless. This situation sets up a whole host of consequences, which make living with the disease a logistical and practical nightmare. Adhering to a strict medication regimen and suffering from debilitating side effects (e.g., diarrhea) is difficult enough when one has a home; without a stable living environment, adherence may be impossible (see Sollitto, Mehlman, Youngner, & Lederman, 2001 for a review of the literature). For economic reasons, some may have to live with roommates, family members, or partners. In these cases, they may be at risk of eviction or loss of the relationship if their HIV-positive status becomes known (Simoni, et al., 1995).

Another challenge poor, urban drug users face is rooted in the dynamics of addiction. Drug users who are dope sick (i.e., suffering from withdrawal) may not be in a position to take the necessary precautions to prevent secondary HIV transmission. Some drug users discuss the guilt and fear they feel about situations in which they have put others at risk of infection. In many cases, if their peers fail to take self-protective measures, the HIV-positive drug users bear the onus of responsibility to disclose their serostatus. Social relationships in such contexts are often tenuous, and the ramifications for such disclosure could be perilous. That is to say, the knowledge that someone with whom an individual has engaged in risky behavior is HIV-positive might put that person at risk of violence or financial cut-off (Rothenberg & Paskey, 1995).

Many HIV-positive drug users also have inadequate or nonexistent health care or insurance, which may contribute to limited access to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) (Menke, Giordano, & Rabeneck, 2003). Further, with limited income, they may be faced with the choice of purchasing illicit drugs, which have an immediate and positive effect, or HIV drugs, which may likely result in noxious side effects and delayed or inconspicuous health benefits (Ammassari, et al., 2001). An apparently simple act like arriving at a medical appointment on time is complicated by poverty and drug use. Those who do not have ready access to transportation may have to rely on erratic bus schedules or even walk to appointments, sometimes in a compromised state of health. Healthcare providers may also be biased against providing adequate care to drug users, maintaining an unofficial prejudice that they did this to themselves, or believing that they could never adhere to the treatment regimen, despite a lack of clear evidence of their ability to predict treatment adherence (Sollitto, et al., 2001). HIV-positive drug users may be afraid to admit drug use because of such stigma, which might have deleterious consequences due to illicit and pharmaceutical drug interaction effects.

Personal relationships among drug users tend to be compromised due to poverty, addiction, and HIV infection (Fals-Stewart & Birchler, 1998). Rather than referring to their friends, drug users often talk about drug associates on whom they rely for practical or emotional support until an event occurs that results in a complete breakdown of trust. In fact, those individuals on whom they come to rely may be as vulnerable to the social consequences as they are. Alienation by family and friends because of drug use is also a common experience (Carroll & Chambliss, 1990), as is an unwarranted fear of contamination (Falkin & Strauss, 2000).

Unlike illnesses with similar trajectories, the etiology of HIV infection (e.g., sharing of contaminated drug injection equipment, sexual intercourse with an HIV-positive person) has been incorporated into a moral system in which shame and projected blame are paramount, creating as much or more suffering than from the biological aspects of infection. Moreover, people living with HIV disease are not a uniform population. For some, HIV is their primary health, interpersonal, and emotional concern; for others it is just one of a litany of life challenges. For the latter, HIV/AIDS contributes to the experience of what might be called multiplicative stigmatization, that is, moral reproach across multiple personal attributes and conditions. Drug users living with HIV disease, for example, do not merely suffer from a potentially lethal disease, nor do they endure social suffering and stigmatization only on the basis of having what some see as a disease of immorality. Rather, they are subject to stigmatization born of condemned behaviors, denigrated lifestyles, and often, being members of socially devalued ethnic or sexual minority groups as well. While the stories of some people living with HIV/AIDS have been told, these usually have not been the stories of inner city drug users.

Purpose

Injection drug users have constituted 36% of people with AIDS (Centers for Disease Control, 2004) and they confront special challenges in accessing and maintaining effective treatment and meaningful care. The purpose of this article is to illuminate how current or recent street drug users dealing with HIV frame their illness, taking into account the diversity of experiences and unexpected responses to illness and death they might have. In so doing, we hope to highlight the multiple stressors as well as sources of support or comfort that this largely hidden population has, as well as to challenge the notion that HIV positive drug users fail to make efforts to improve their health after being diagnosed. In the end, we will provide a theory that represents the themes presented by HIV-positive drug users in a mid-sized U.S. city. Optimally, physical and mental health care providers or other caregivers will benefit from this information and consider multiple aspects of the illness experience for HIV-positive persons who have other significant life struggles, including poverty and addiction. Further, this research might inspire other researchers to consider how the experience of HIV is similar to or different from people's experiences of other chronic, non-reversible, incurable, or debilitating illnesses that may be invisible to others (c.f. Hydén, 1997 and Williams, 1984 in Hänninen & Koski-Jännes, 1999).

The people providing the narratives in this article are illicit drug users living in poverty in Hartford, Connecticut. Some have tried to beat their drug habit; in fact, many that we interviewed were in some phase of the recovery process. Many were also afflicted with various diseases besides HIV, including other sexually transmitted infections, mental illness, diabetes, and cancer (Singer & Clair, 2003). Some have had experience selling sex in exchange for drugs or money. These issues also have a clear influence on their experience of life—and the possibility of death. Marginalization, whether it has occurred as a result of racism, poverty, drug addiction, or illness, magnifies the impact of having HIV. Thus, their experiences with illness are very different from those HIV-positive persons who are privileged in real and important ways. Elsewhere (Singer, Scott, Wilson, Easton, & Weeks, 2001) we have examined the life experience narratives of active street drug users. Although it would be useful to compare their narratives with non-drug using HIV-positive persons, such a comparison is beyond the scope of this article. We will utilize two existing categorical frameworks to begin to look at the illness experience of drug users (Boss & Couden, 2002; Frank, 1995; Frank, 1998).

Narrative Frameworks

Arthur Frank (1998) has argued that people suffering deep illness tend to tell three predominant stories. He defines deep illness as that which is “perceived as lasting, as affecting virtually all life choices and decisions, and as altering identity” (1998, p. 197). These stories include the Restitution narrative, the Chaos narrative, and the Quest narrative. The Restitution narrative exists because of the relative efficacy of medical professionals to adequately diagnosis and treat physical illnesses. As told, this story follows a general linear trajectory, in which an individual becomes ill, but through medical intervention, regains health. This is a popular and pervasive account. Most people tend to assume that health will be restored, sometimes even in light of a serious diagnosis, such as cancer. When medical interventions fail, the person may feel a sense of injustice or incredulity, leaving him or her angry, in despair, or in disbelief. The belief that a restoration to health will ultimately occur in the future and it is simply a matter of time before that takes place may follow these feelings. Some people cling to the hope of restoration until they die.

In contrast, the Chaos narrative is filled with uncertainty, confusion, and a sense of powerlessness over events in one's life. It refers to the perception that everything is falling to pieces. For the listener, this can be the most difficult account to hear; Frank (1998) has described this story as suffocating. For this reason, the Chaos narrative is likely to be subverted, if not by the person telling it, then by the person listening to it. A common thread in this narrative is a sense of never-ending suffering and a series of negative life events that either contribute to the experience of the illness, or are exacerbated by its presence. Frank (1995) has argued that listeners are most frightened of the Chaos narrative because it forces them to recognize their own vulnerability to illness. It is unnerving and isolating to consider that one might neither regain health nor become spiritually transformed by the illness experience.

Transformation through illness is evident in the Quest narrative. In this account, it is unnecessary for a person to return to health, like it is in the Restitution narrative. Rather, in the Quest narrative, a metamorphosis occurs. A failure to return to one's previous state is compensated by the emergence of an optimal state. For example, a person with HIV disease might suffer and eventually die, but after her HIV-positive diagnosis, she becomes an advocate for those who are also afflicted with the disease. Her transformation does not result in a return to physical health; however, it helps her gain emotional clarity, and for the first time, a deeper sense of meaning. While listeners to illness narratives may be most comfortable with Restitution stories, in the absence of such accounts, they may hope for Quest narratives. Sometimes, the Quest narrative may be encouraged, with the hope that it reflects part of the journey en route to Restitution.

In Boss and Couden's (2002) conceptualization of ambiguous loss, they highlight the potentially inconsistent physical and psychological realities in relation to death or dying processes. This inconsistency arises, for example, if one comes to terms emotionally with death but death fails to arrive at the expected time. This would be the case for those individuals who have had going away parties and spent all their life savings, only to realize that death did not ensue neatly behind their acceptance of it. The ambiguity of loss framework highlights the real difference between physical and psychological or spiritual realities. This framework may be used to evaluate the narrative accounts of those living with HIV, particularly because these individuals struggle with some degree of physical deterioration and the burden of living with a life-threatening illness that may or may not be evident to those around them.

Some researchers have addressed the question of how people with HIV or AIDS frame their illness. However, many have examined HIV through the lens of physical deterioration and the eventuality of death. The present context of HIV is one of ambiguity and uncertainty, particularly because many of the individuals who provided these narratives have experienced either no symptoms or mild to moderate symptoms. They have not yet had to confront physical limitations, despite having known of their illness for a considerable length of time. Building on the frameworks of illness narratives and ambiguity of loss, we will elucidate the stories of active or recovering drug users living with HIV, and investigate ways in which these narratives diverge from the stories identified by Frank (1995; 1998). We will also illustrate the diversity of experiences people with HIV have and look at trends to formulate hypotheses about the life contexts of those who tell particular stories.

Methods

Procedure

The data for this analysis were drawn from in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 60 individuals who participated in a larger study of HIV risk and prevention among active heroin and cocaine users recruited through street outreach in Hartford, Connecticut (Longitudinal Studies of AIDS Risk Among Drug Users, Grant R01 DA11359-03). The interview protocol and informed consent procedures were approved by an Institutional Review Board in accordance with the American Psychological Association's (APA) ethical principles for research (APA, 2002). The interviews took place between December 1998 and September 2000. Participants involved in the larger study who reported being HIV-positive were recruited for participation in this study. All participants provided informed consent. The semi-structured interviews generally lasted between 1½ and 2 hours and participants were paid $20 for their time. Participants were asked questions pertaining to HIV drug- and sexual-risk behaviors, religious beliefs, life plans, relationships, and work-related issues both prior to and since diagnosis. Additionally, they were asked the following questions to ascertain their personal constructions of the meaning of HIV:

What does HIV mean to you? How does HIV affect you? Why do some people get HIV but others (engaging in similarly risky behaviors) do not? How has HIV affected how you see yourself?

Participants were also asked about HIV-related issues, such as treatment adherence/compliance, disclosure, and disease-related discrimination. Interviews were primarily conducted in English by the second author; other project staff conducted the remainder of the interviews, particularly those in Spanish. Efforts were made to ask open-ended questions and probes were used to clarify and expand participant comments. During the process of being interviewed, one participant became upset when discussing her concern about her children's future. In this case, the interviewer asked the woman whether she would like to take a break or terminate the interview altogether. The participant decided to continue the interview and declined support services referral information. No other such incidents occurred in response to study activities.

Interviews were audiotaped, transcribed, and analyzed for themes by the first two authors. In contrast to a traditional narrative analysis in which the unit of analysis is the entire transcript (Rice & Ezzy, 1999), we examined the diversity of themes both within and between transcripts. Two methodological approaches influenced the methods used for this study. Grounded theory allows a typology to emerge from the data (Strauss & Corbin, 1997); however, Frank's (1995; 1998) Illness Narratives and Boss and Couden's (2002) Ambiguous Loss theories provided an initial reference point from which the analysis commenced. Sandelwoski and Barroso (2003) have argued that qualitative researchers utilize a variety of semantics in describing their research methods and that there is often no relation between the description and the subsequent data transformation and enumeration of the findings. They propose, instead, a classification of qualitative findings according to the degree of data transformation. To this end, our data analysis reflects a conceptual/thematic description in which the “findings are rendered in the form of…concepts or themes either developed in situ from the data or imported from existing theories or literature outside the study” (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003, p. 913). We identified illness narratives that diverged from Frank's (1995; 1998) narrative categories and noted them for further coding scheme development. During weekly meetings, we came to agreement regarding the themes and developed the conceptualization of the proposed framework. We achieved redundancy of themes after having reviewed 50 interviews (83%), but we decided to review all 60 interviews to ensure that complete saturation was achieved. The results presented here contain the conceptualization deemed to provide the most parsimonious representation of the data.

Participants

The 60 participants in this study were predominantly Puerto Rican (48%) and African-American (45%). Sixty-eight percent were male and 32% were female with a mean age of 41 years (range = 27 to 60 years). Over three-quarters (78%) were unemployed and most (90%) had no private health insurance. They were all either HIV-positive or diagnosed with AIDS. One participant reported having been diagnosed with HIV in 1977, before tests to detect HIV antibodies were available. The rest of the participants reported having the disease for a period of time ranging from 0 to 15 years (mean and median = 7 years) and all but two individuals, who died within six months after the interviews, were medically stable at the time of the study.

Results

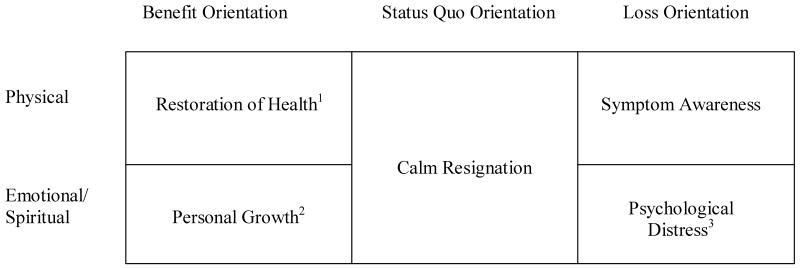

The narrative types Frank (1995; 1998) provides were evident in the accounts our participants told. Alternative narratives were also present and required an expansion of his theory to provide for them. We developed a conceptual framework reflecting three distinct orientations located within distinct physical and emotional/spiritual dimensions1. The modified thematic structure used to explain these data is presented in Figure 1. We will present each category in the matrix in turn. The Status Quo orientation, however, will be discussed last.

Figure 1. Illness Narratives Among Drug Users Living with HIV/AIDS.

1Incorporates Frank's (1998) Restitution Narratives

2Incorporates Frank's (1998) Quest Narratives

3Incorporates Frank's (1998) Chaos Narratives

Benefit Orientation

Restoration of Health

A focus on the movement from illness to health was evident in many narratives despite of the fact that there is no known cure for HIV. Faith in the restoration of health is not surprising or even illogical, particularly given that many individuals have outlasted their prognosticated life spans, despite the fact that many of our participants were either not involved in antiretroviral regimens or they were taking medication inconsistently at the time of the study. Janice2, a 53-year old woman who had been living with HIV without symptoms for eight years at the time of her interview, believed that she would not be a statistic and that HIV has a less certain course than other diseases, such as cancer.

You know how they have them talking movies; talking about that they only go up to ten years. You only could have HIV, the virus and AIDS…you know you die within that ten years. The system [body] could [not] keep that in there. I just wouldn't believe that….when we were in the groups talking about [it], I said, “That's impossible. People could live longer than 10 years if you take care of yourself. By right can't nobody determine when you are going to die other than if you had cancer.” I said, “No doctor, nobody can tell you when you are going to die.”

Janice also indicated a strong internal locus of control, or a sense of personal responsibility and an ability to respond to HIV. She started a drug treatment program after finding out she had HIV, “so I decided to take care of myself to last a little longer.”

At times, and perhaps unsurprisingly, desperation appears in a person's investment in the restoration of health. As Harry pointed out:

I'm comfortable with what I have but I just want this thing, you know, I just want it to turn over so I can get back to life again and be healthy again. I don't mind if I have this virus. Even though I have it, I still want to live, you know what I mean? I don't want to die. Let me just live the way I'm livin' right now but don't take me away.

Harry appeared to be pleading for his life, which is a common experience when one is coming to terms with a life-threatening illness (Kubler-Ross, 1969).

The reliance on antiretroviral medications and the hope for the next medical advance that puts these individuals one step closer to a cure was often suggested, even if tentatively, and the anticipated movement toward health was clearly implied. Mark, a 50-year-old man who has lived with HIV for eleven years believed that medication would inevitability lead toward a restoration of health:

P: I don't know how it is doing yet, but I know [subsequent] to me starting with this new one that my T-cell count has been climbing and my viral load has been dropping. So it's been ok.

I: So it's working.

P: Yeah obviously I am doing very good.

Mark does not clarify what “doing very good” means, exactly, although the idea could take on several meanings. He could be referring to the temporal indicators of improved immune system functioning; however, the implication is that he is moving toward health and moving further away from illness.

Notably, other participants not only reported coping well with the disease; they reported that having the disease, in a sense, saved their lives or that they were physically stronger as a result of having the disease. For them, drug abuse and addiction appear to pose even greater threats than imminent deterioration and possible death from AIDS-related complications. For example, Eugenia, a 53 year-old woman, described what HIV means to her:

It doesn't mean I am going to die today. It would have meant I could have died tomorrow or a week from now if I didn't change my life around. If I had continued to use drugs and not try to go and see what AIDS is all about and the treatment that is needed- yeah, I would have died.

Likewise, after describing the disease process in pathological terms, Alexandro, 37, personalized his response and added,

Physically…right now I feel like I could do a hundred push ups, like…I dance a lot…I haven't done that in twenty years, so…I feel good! I feel real good. On a scale from 1 to 10-- probably 9.99.

This projects an image that he could hardly feel better, even if he were HIV-negative. Many other individuals reported that they took better physical care of themselves as a result of the diagnosis, including stopping drug and alcohol use, adhering to antiretroviral regimens, eating regularly and more nutritiously, and using alternative treatments, such as Maguey roots.

A common metaphor used among those who were focused on a restoration of health was that of HIV as a battle to be fought. For example, “I realized that there were people who still loved me and that it is worth fighting for my life.” In some cases, belief in God played a particularly central role in this fight and/or was the reason for an actual or expected miraculous recovery. The following examples illustrate this:

Now that I found out I was positive, I said, “I am going to live with this disease because of my faith.” (Eduardo, 38 years old)

I thought I only had a short time to live. I said, “Oh my God, What am I going to do? You are the only one who can help me or take me away.” Then I felt normal again, so I said, “Maybe it's a miracle.” (Angel, 49 years old)

He [God] is my doctor, my medicine. (Marisol, 38 years old)

One man, who had been diagnosed three years earlier, reported believing in the miraculous intervention of God, although not for himself:

I know I'm going to die from this, but I still believe that God will make a way for the ones that have it…he will cure. Some people say they have gotten to a point that it [the virus] is undetected and I think that's a good sign for someone.

Good luck and uniqueness of self in contrast to other people living with HIV were also expressed. Uniqueness, for example, was represented by accounts of miracles or good luck involving extreme health, often to the astonishment of the medical professionals involved. For example, Ricky, a 51-year-old man who had known his status for over eleven years, explained:

If anything I think, “Lucky me, having it and having no symptoms. Look how lucky I am.” Look how special I am, if anything. It's crazy but in some way it's been a blessing. I think the fact that here I got this thing that's killing people and some people have lived very short periods of time and some people live longer periods of time and they're on medication or change their lifestyle and here I didn't do a damn thing and I've lived all this time. To me that's some sort of, I'll use the word blessing, you know, I just use that for other people, but, no, I think that makes me very special, as crazy as it sounds.

In the context of stigma and rejection associated with drug addiction and HIV, Ricky's comment reflects his own astonishment that such luck has fallen to him. Such narratives that reflect an individual's awe with his or her own uniqueness or good fortune, including narrow escapes and miraculous gains, were found in our previous research with similar populations (Singer, et al., 2001).

Personal Growth

Personal growth narratives, not unlike Frank's Quest narrative, also consider the ‘benefits’ of the illness, but from a spiritual or emotional standpoint. Such stories have also been identified among individuals coming to terms with the illness of drug addiction (Hänninen & Koski-Jännes, 1999). In our interviews, this was true with regard to spiritual or emotional enlightenment. Some participants maintained that HIV had provided them with an opportunity to change their psychological, interpersonal, or spiritual lives in some way. In some of these narratives, participants viewed their experience as one that resulted from uniqueness or good fortune and God's intervention. Some appeared self-righteous in this description, suggesting that others living with the disease had not reached their own level of enlightenment, or alternatively, that those who did not have the disease continued to squander their good health with bad habits.

Many spoke of a journey toward becoming a better individual as a result of the experience of living with HIV, invoking particular subplots. For example, some provided the interviewer with an image of the perfect patient, who, barring a healthy recovery, has learned something very important. Some discussed making up for past mistakes. Others focused on HIV as a wake-up call of sorts. Finally, others indicated that they were using their disease as an opportunity to connect with family members, friends, or even strangers. They liked to think of themselves as reaching out to those in need. Some connected that need to God's will, as did Tom, who has lived with HIV for seven years:

The way I'm starting to look at it is that God got a plan to make you wake up and see things sometimes from this virus, to make you stop doing what you're doing, killing yourself…I guess he wanted me to stop suffering and start looking inside myself and he present this virus to me and said, “Hey this is it! You want to keep doing this and die or do you want to live and look at life on life terms?” And it worked. That's why I think I got the virus, to make me look at things a little closer than I was. Make me change my lifestyle, look at people in a different kind of way and surround myself with good people rather than bad people and the bad things out there. That's what I think.

Similarly, Genny, a 37-year-old woman who has had the virus for four years, talked about needing to reach out to others:

[I have to] show-- not show people, but let people understand that because you have this and you can't do nothing, you still can accomplish anything in life regardless if you are sick or not. You understand what I am saying? I'm a fighter. This is not going to stop me from doing what I want to do.

Both of the previous quotes provided a sense of what living with HIV and drug addiction is like. For many of the participants, getting an HIV diagnosis prompted them to consider getting treatment for their drug abuse. While this was certainly not the case for all participants, and not all who wanted to get clean experienced success, both HIV and drug addiction are viewed as challenges to overcome. These challenges provide the individual with valuable life lessons and a forum within which to start over.

Some participants moved beyond an internal reflection of the lessons the disease had provided them and projected these lessons onto others. An artifact of this for some was a sense of self-righteousness. For example, Carmen, a 53-year-old woman, complained:

That's why a lot of people kills me when they get to screaming, “Why me? Why me?” When we go to the meetings, I be mad…they be mad, but I tell them, “Why you? Because you picked up the needle and did it or you had sex with the wrong person.”

She added, in response to the anger people express at God for the infection, “I say, ‘You know damn well (laughs), the Lord didn't give you HIV and He damn sure didn't put that hypodermic needle in your arm.’”

Although one might expect to find those afflicted with HIV to be understanding of others with the infection, particularly given the stigma commonly attached to it, some participants appeared to project their own shame onto others who are in similar circumstances. Internalization of stigma associated with having HIV infection may magnify a life pattern of being subjected to damaging social messages stemming from exposure to racism, sexism, discrimination against the poor, and prejudice against drug users (Singer & Weeks, in press). Hydén (1997) has highlighted the question of morality as it relates to illness. He suggests that one uses illness narratives to question the extent to which one is responsible for one's illness and the extent to which one is a victim of it. In the same regard, once an individual has become infected and internalizes societal stigma, she may have had a possibly unconscious need to distinguish herself from other HIV-positive persons or other drug users in order to situate herself in a different, if only slightly elevated, moral category. This is reflected here in the narrative indicating self-righteousness in comparison to other addicts regarding their handling of HIV, and it is a common theme in narratives about drug addiction itself.

Loss Orientation

Symptom Awareness

We asked participants about their symptom experiences. We received a wide range of responses. A few individuals indicated that they had not experienced any symptoms. Others reported having felt better after a period of illness, either with or without medication. Some reported only having side effects from antiretroviral treatment. Others reported having had HIV-related symptoms, such as pneumonia, fatigue, weight loss, diarrhea, darkness of fingernails, and skin dryness. Participants identified symptoms that may have been related to drug abuse or withdrawal, or corporal damage due to chronic drug use. In addition, some participants reported other serious medical and psychological conditions, such as cancer, renal failure, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder, making it difficult to distinguish which conditions were related directly or indirectly to their HIV serostatus. Further, because of the damaging effects of poverty (including poor health maintenance and limited access to state-of-the-art treatments and medical support), drug addicts may experience more severe symptoms than other HIV-infected individuals (del Borgo, et al., 2001; Sollitto, et al., 2001).

Individuals clearly have diverse experiences with regard to symptom presentation and tolerance. Pain and suffering are subjective experiences, and one can only rely on another's self-report to get a sense of the degree to which he or she is discomforted, inconvenienced, or made miserable by illness (Rotheram-Borus, 2000). Those living with HIV also have varied degrees of symptoms. Many symptoms can be objectively observed and measured, such as weight loss, diarrhea, or respiratory infection. Still, despite the objective presence or absence of certain symptoms as confirmed by medical diagnostics, one's perspective or framing of the symptom event can have a great influence on the degree and manner in which one copes or fails to thrive. Although we specifically asked about symptoms, participants varied in the degree to which their focus on symptoms influenced their perspectives on living with HIV or other aspects of their functioning.

Two subthemes emerged from discussions about symptom experience. These included a focus on physical deterioration and the embodiment of HIV, particularly with regard to the fear of deformity or having the appearance of being someone who is sick with HIV-related symptoms. Juan Carlos provided the following description of living with HIV:

I feel like something is aching inside my body. I believe it is the HIV because sometimes I can't sleep because sometimes I just start thinking about it, that I got it and I be up all night. And I don't know if it's that, why I am losing weight too because of the worries; I'm thinking, “Whoa, when is it going to be the day that I am going to [die]?” you know, and it's hard for me.

Mary, who had lived with HIV for six years, provided another description:

I can [tell]…my body is getting smaller, like something sucking me at like the neck, and everything's gonna get stringier and weaker, and I know this. And everything's showing, like my ribs and stuff, and the flab outside my face is gonna sink and I know this.

Such comments about increasing evidence of the disease also suggest concern that these participants will no longer be able to hide their status and protect themselves from the multiplicative stigmatization of HIV infection and drug addiction. In fact, internalized stigma has been associated with severity of symptoms (Lee, Kockman & Sikkema, 2002) and the appearance of external symptoms (Herek, 1999).

Psychological Distress

Internalized stigma appeared to be associated with psychological distress, as participants provided vivid details about the anxiety resulting from either the actual presentation or the anticipated or feared manifestation of those symptoms. Distorted personal appearance as a result of infection and medical treatment was of special concern:

It's a slow death, I think. That['s] what bothers me a lot, the appearance part of it. When I see those scars, I hope it ain't going to be all over my face….knowing that I won't be able to get around like I normally do. When I see people [who are HIV positive], they can't really get around. Those are the things that worry me the most. The only medication side-effect I got was the darkness of the fingernails and the dryness of the skin. I would do anything to keep my appearance; I didn't want to be sick. Some people look healthy and then there are those that really look sick. And my biggest scare is looking sick; not just feeling it but looking sick.

One participant discussed having considered suicide in the face of physical deterioration. Referring to another HIV-positive person, Jacki explains,

Yeah, and he'd look so skinny like this pole in here. I don't want to get that way. I wouldn't want nobody to see me like that. Because it's not a good sight to see. If I get to the point where my T-cells get that low and I get that way, I don't know what to do. I've been thinking about trying to end it before it gets that way.

Here, body image concerns related to HIV infection rather than symptom experience or pain appears to be driving the consideration of suicide.

Other psychological issues involved fear related to the suffering that participants were or would be causing others, losses that the illness represented (e.g., not being able to have children or not being able to see a grandchild get married), and fears of death. Some participants seemed to be caught within a web of despondency, depression, and suicidality either directly or indirectly related to their illness. Indirect concerns included the psychosocial factors that were present before the onset of the HIV diagnosis, but were perhaps exacerbated by it (e.g., poverty, drug use, alienation of partners, domestic violence, mental illness) as well as stress from HIV-related stigma or the fear of the repercussions from such stigma. The dynamics of poverty and addiction had left many individuals without income, employment, or familial support, and in poor health.

Some participants reported using drugs as a way to cope emotionally with the infection or as a means to end their lives. Grant, a 48-year-old man, started injecting heroin and cocaine at the age of 16. At the time of the interview, he was in drug treatment and reported:

You know, and especially after I found out that I had the virus, that was my goal, was if I was going to die, it would be behind shooting drugs, you know? And then I just felt like my life was totally lost and that I had lost my self-esteem, and I didn't care. A lot of different…feelings hit me. And I just…said, “Well, I will deal with it the way I know how.” And the only way I knew how to deal with it was to get high every day to try to escape it.

In fact, a common theme among some participants was the desire to avoid thinking about their illness. Friends and family had given the advice to not think about it, and for those who reported a desire to avoid the topic, they tended to believe that thinking about it would either make them become critically ill or severely depressed. Ironically, none of the participants who reported having such beliefs appeared distressed during the interview nor did they express a desire to stop talking about it.

Status Quo Orientation

Demonstrating the diversity of illness experiences, some participants appeared to have a laissez-faire attitude about coping with the illness or accepting death. We understood these apparently ambivalent responses to be significant and relevant illness narratives, yet they did not fit neatly within any of the aforementioned benefit or loss narrative categories. The following are striking examples illustrating maintenance of the status quo and a calm resignation about the inevitability of death. In response to questions about changes that have happened since his diagnosis, Richard reported:

Sometimes I get a little disappointed with myself now, whereas I didn't before. You know, overall, I still care about me, I still take a shower every night, I still get up and brush my teeth and, you know, try to keep a little hair cut, keep my face done you know….I'm still living, so…You know that I can't do what I used to do, but that's cool.

He continued, saying how he is “living one day at a time.” Taking each day as it comes is promoted in the Narcotics Anonymous (NA) literature (NA, 1987), and evidence of this type of status quo maintenance might well reflect participants' socialization into this conceptual framework through prior experience with 12-step drug treatment or support groups.

Other participants discussed death as something inevitable and just another prosaic part of life. After talking about his idea of what a happy life entailed, Ron was asked about priorities for the rest of his life. He reported that the financial priority was simply to have life insurance so that his family could afford to bury him. Some did not seem to show particular distress about death and presented a rather mundane picture of it. Victor reported, “Everything is still the same. Because I am not going to change just because I'm sick. I'm sick, yes. But everybody's going to die, not just me.” Similarly, Johnny stated:

You could die from anything; you could go into the hospital and die, you could get shot, etcetera. I don't really care because I am already fifty and I feel that I have lived long enough; and I know that once you start getting old you start getting sick and die from anything.

Religious faith appeared to play an important role in understanding death. Although faith seemed to help in dealing with the inevitability of death, ambivalence remained for Carol, 38 years old, who said, “When God wants to take me, he'll take me, with or without medication. However, I do try to protect myself and not get others infected.”

It is important to consider this ambivalence and sense of the inevitability of death in the broader social context in which these participants live. Many have experienced the death of numerous relatives, friends, and community members. Poverty, illness, and violence are often more immediate threats than the risk of AIDS-related death. Many drug users are subjected to violence in various forms, beginning in childhood and continuing in their intimate relationships and on the street (Duke, Teng, Simmons, & Singer, 2003). Death may also be something that drug addicts are less insulated from than others in the wider community, and it might not have many of the anxiety-provoking connotations that other experiences have. In this context, the presence of this narrative type among HIV-positive drug addicts reflects the sense that death is close even in the midst of mundane daily activity.

Discussion

The purpose of this article was to shed light on how HIV-positive drug users experience their illness, and the words that they assign to these experiences. We have developed a typology to classify their illness narratives. Using Frank's (1995; 1998) illness narrative framework as a starting point to categorize narrative types, we constructed the model presented here that explained more completely our participants' experiences of living with HIV or AIDS. These diverse narratives reflected three primary orientations (Benefit, Loss, and Status Quo). The narratives differed with regard to the emphasis given to either physical or emotional and spiritual implications of the illness.

Themes reflected within the physical dimension of a Benefit Orientation included the belief in a restoration of pre-diagnosis health status, and in some cases, an improvement of health beyond that which was experienced prior to known seroconversion. Although some evidence in the literature indicates decreased clinical progression of HIV due to antiretroviral therapies (Henry, et al., 1998) or coping strategies (Mulder, Antoni, Duivenvoorden, Kauffmann, & Goodkin, 1995), there has not been evidence presented in the literature of functioning exceeding premorbid indices. Three factors might be particularly salient to explain this phenomenon. First, an HIV diagnosis for some of our participants seemed to signify, in both perceived and substantive ways, a second chance to move from a life of chaos and addiction (Holmes & Pace, 2002). This was evident in narratives referring to a healthier, more stable lifestyle, sometimes including decreased drug use or complete abstinence. This response may be fed by an underlying optimistic sense of hope that is pervasive in Western culture: a sense that it is almost never too late, as well as a belief in the capacity of the individual to take action to make things right in the world. Second, some participants in our study became intimately involved in their medical care; they worked in tandem with medical providers and co-created supportive relationships in their battle against disease progression. Although we had reason to expect participants to provide accounts of dubious and perhaps dehumanizing interactions with medical personnel (Roth & Nelson, 1997) particularly given the constraints they faced as a result of enduring multiplicative stigmatization (e.g. poverty, drug use/abuse, marginalized racial categorization), participants reported having generally positive and supportive relationships with medical personnel. It is possible that this finding may be a consequence of grassroots AIDS activism, which may have resulted in heightened sensitivity among physicians who treat patients living with HIV or AIDS. Whatever the source, such interactions can help to redirect participants' notion of self-care and facilitate the effects of medication via improved compliance and treatment adherence. Finally, some have argued that HIV serves as an important commodity among people living in poverty; having HIV essentially entitles one to improved access to supplemental income, housing, food, services, and medical services (Crane, Quirk, & van der Straten, 2002), thereby potentially improving their quality of life and hope for the future beyond what was possible before diagnosis. While we found no evidence of intentional infection, and doubt that it occurs very frequently, there is no denying that a diagnosis of HIV infection opens doors to resources often unattainable by those who are not infected.

Importantly, although some participants reported having had success with HAART, others did not use such protocols due to an inability to consistently take medication, noxious side effects, or even a belief that God was their medicine. Further, involvement in HAART did not account for the numerous narratives focused on a restoration to health. Essentially, HAART was viewed as one of many pathways to health, despite overwhelming evidence that it has caused at least preliminary decreases in AIDS deaths over recent years (HIV Trialists' Collaborative Group, 1999).

Emotional or spiritual benefits were also perceived as a result of an HIV diagnosis. Similar to the perception of a second chance at physical redemption, participants also cited a second chance for personal growth. Improved relationships with God and one's family seemed to be at the core of this category. This is a particularly encouraging finding, as some researchers have found that relational stressors and a lack of social support might be important contributing factors in a hastened transition from HIV to AIDS (Leserman, et al., 1999). For some participants, distressed family relationships may have contributed to initial drug abuse; for others, these relationships were ruptured as a result of the participants' drug involvement. The diagnosis may have served as a wake-up call for all relevant parties, reminding them that they might have just one last chance to mend damaged relationships before death ensues. Of course, those involved in drug treatment, and particularly those in programs operating from a 12-step paradigm, may also be actively working to reconcile with people they may have hurt as a result of drug addiction. Finally, a certain moral awareness of the dangers of addiction and engaging in behaviors that put individuals at risk for HIV seems to have propelled some participants into the realm of outreach and public support of others who are also at risk of HIV and drug relapse.

As expected, loss narratives were also evident. As with benefit narratives, we found that loss narratives primarily emphasized either physical or emotional and spiritual losses. This is not to say that physical losses were not experienced psychologically (Rotheram-Borus, 2000). On the contrary, it is clear that these dimensions are not mutually exclusive; however, the difference in emphasis participants provided with regard to these two realms was great enough to require distinct categories in our thematic framework. Although the presence of an immune-suppressing virus unequivocally involves at least some degree of physical loss or impairment, the degree to which participants became preoccupied with such loss varied substantially. Concerns about the markers of disease progression were evident, as was trepidation about a variety of known symptoms of HIV infection. Certain symptoms were of greater concern and these appeared to have less to do with the gravity of the symptom or even the degree to which it threatened significant impairment or suppressed immune functioning. Rather, visible symptoms that were associated with HIV in particular were those that caused the greatest concern. Some feared that “looking HIV” would lead to discrimination. For others, such signs were evident in others they knew who had not survived; in this case, these clearly signal impending death. As this discussion suggests, AIDS stigma is every bit as and possibly more damaging than HIV disease itself (Singer, 2003).

Spiritual and emotional losses were evident in individuals who provided accounts of depression, hopelessness, and despair. These experiences, although occurring in the context of HIV infection, probably cannot be extrapolated from the sociocultural realities and structural violence that surrounds our participants. It is beyond the scope of the article to examine the etiology of spiritual and emotional losses; however, addiction, poverty, racism, stigmatization, and other health complications surely contributed to a sense of loss and despair.

Surprisingly, another category of responses that did not fit into either a clear Benefit or Loss orientation also emerged. We identified a Status Quo orientation in which the participant seemed neither particularly distressed by the inevitability of death, nor focused on a life of physical renewal or personal growth. Instead, these participants provided narratives that portrayed HIV as a part of expected life struggles. These individuals seemed to be focused on their day-to-day needs and did not report spending much time thinking about HIV beyond what was necessary for daily living. There may be any of a number of reasons participants provided these types of narratives. Some HIV-positive people we interviewed had relatively few physical symptoms and were not forced to attend to HIV-related ailments on a regular basis. Other individuals might have experienced a number of major problems in their lives and HIV might truly be just one of multiple health or psychological issues on their plates. Given such realities, they may have many more proximal concerns than HIV, including finding employment, maintaining sobriety, or repairing damaged familial relationships. In any case, the Status Quo orientation provides important information about some people's experiences with the disease that might incorporate neither hopefulness nor despair. These narratives may well reflect the transition that has occurred between an earlier focus on HIV/AIDS as death to viewing it as just another chronic disease.

Some important limitations must be addressed. Participants in our study responded to questions about their experiences of living with HIV in a single interview. The retrospective accounts may certainly have been dependent upon the peculiarities that these individuals were experiencing at that particular moment (Ezzy, 2000). It would be interesting and informative to note how and why or whether the individuals we interviewed moved from one narrative to another throughout the course of their illness. Longitudinal assessment of this sort, while necessary to understand individual trajectories in the face of this disease, was beyond the scope of our study.

A second limitation relates to cultural assumptions and meanings given to illness narratives. Although we are not assigning value to particular stories, the very task of identifying predominant narratives and categorizing them is inherently culturally bound (Ezzy, 1998). We may have conceptualized these differently because of our particular cultural backgrounds and experiences (Miczo, 2003). We have taken efforts during the course of the analysis to discuss our findings with members of our research team who represent a variety of ethnic, age, and experience diversities. Likewise, we have carefully considered how our own experiences with illness and conceptualizations of the illness experience have influenced our interpretations of particular stories.

Important questions remain for us. What would these stories look like in a different population? How does HIV-related stigma influence the story telling, particularly the public telling of the story? That is, can the politics of being HIV-positive be extracted from the solitary and perhaps lonely experience of living with concerns about one's own mortality and truth in existence? What does a life of poverty, drug addiction, and ambivalence toward social service organizations contribute to the telling of the account? It is important for physical and mental health care providers to consider the politics of certain narratives, their own biases, and the dynamics of the relationship with the patient that might make some illness narratives more or less likely to be told. This acknowledgment will help those working with HIV-positive individuals to understand and validate their experiences more fully. Despite the questions that remain, it is evident that HIV-positive, minority drug users have their own stories to tell (Chandler & Kingery, 2000). In that they have long been a marginalized and silenced population, the time has come for others to listen.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) supplemental grant R01 DA11359-02S1 granted to the third and fourth authors (principal and co-principal investigator, respectively). An initial analysis of this data was presented at the ProVisions VII Conference in Hartford, Connecticut (2000). The authors wish to express their gratitude to the participants for their honesty and courage in discussing their experiences of living with HIV/AIDS.

Footnotes

Katie E. Mosack, Institute for Community Research, Hartford, Connecticut; Maryann Abbott, Institute for Community Research, Hartford, Connecticut; Margaret R. Weeks, Institute for Community Research, Hartford, Connecticut; Merrill Singer, Hispanic Health Council, Hartford, Connecticut; Lucy Rohena, Hispanic Health Council, Hartford, Connecticut.

Katie E. Mosack is now at the Center for AIDS Intervention Research (CAIR), Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Our model combines the emotional and spiritual aspects of the illness experience in one dimension. Participants reported particular non-physical benefits and losses from HIV. Some attributed their affective experiences to God or other metaphysical realities. Others, however, connected them with emotional health, including psychological mechanisms and social support. Although these experiences were different enough to be considered separate from physical realities, the data suggested that they were tapping into a single affective dimension.

All participant names have been changed to protect their identities.

Contributor Information

Katie E. Mosack, Email: kmosack@mcw.edu, Center for AIDS Intervention Research (CAIR), 2071 N. Summit Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53202; phone (414) 456-7740; fax (414) 287-4209.

Maryann Abbott, Email: mabbott58@hotmail.com, Institute for Community Research, 2 Hartford Square West, Suite 100, Hartford, Connecticut 06106; phone (860) 278-2044; fax (860) 278-2141.

Merrill Singer, Email: anthro8566@aol.com, Hispanic Health Council, 175 Main Street, Hartford, Connecticut 06106; phone (860) 527-0856; fax (860) 724-0437.

Margaret R. Weeks, Email: mweeks@icrweb.org, Institute for Community Research, 2 Hartford Square West, Suite 100, Hartford, Connecticut 06106; phone (860) 278-2044; fax (860) 278-2141.

Rohena Lucy, Hispanic Health Council, 175 Main Street, Hartford, Connecticut 06106; phone (860) 527-0856; fax (860) 724-0437.

References

- Ammassari A, Murri R, Pezzotti P, Trotta MP, Ravasio L, De Longis P, et al. Self-reported symptoms and medication side effects influence adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in person with HIV infection. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS. 2001;28:445–449. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200112150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychologist. 2002;57:1060–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss P, Couden BA. Ambiguous loss from chronic physical illness: Clinical interventions with individuals, couples, and families. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;58:1351–1360. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JF, Chambliss CA. A comparison of the self-reported problems of alcoholics, drug dependent persons, and multiple drug dependent persons at admission. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 1990;7:3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Drug-Associated HIV Transmission Continues in the United States. 2002 May; Retrieved July 20, 2004, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pubs/facts/idu.pdf.

- Chandler C, Kingery C. Yell real loud: HIV-positive women prisoners challenge constructions of justice. Social Justice. 2000;27:150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Crane J, Quirk K, van der Straten A. “Come back when you're dying:” The commodification of AIDS among California's urban poor. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55:1115–1127. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Borgo C, Izzi I, Chiarotti F, del Forno A, Moscati AM, Cornacchione E, Fantoni M. Multidimensional aspects of pain in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2001;15:95–102. doi: 10.1089/108729101300003690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke M, Teng W, Simmons J, Singer M. Structural and interpersonal violence among Puerto Rican drug users. Practicing Anthropology. 2003;25:28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzy D. Lived experience and interpretation in narrative theory: Experiences of living with HIV/AIDS. Qualitative Sociology. 1998;21:169–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzy D. Illness narratives: Time, hope and HIV. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50:605–617. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkin GP, Strauss SM. Drug-using women's communication with social supporters about HIV/AIDS issues. Journal of Drug Issues. 2000;30:801–822. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Birchler GR. Marital interactions of drug-abusing patients and their partners: Comparisons with distressed couples and relationship to drug-using behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12:28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Frank AW. The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Frank AW. Just listening: Narrative and deep illness. Families, Systems, & Health. 1998;16:197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hänninen V, Koski-Jännes A. Narratives of recovery from addictive behaviours. Addiction. 1999;94:1837–1848. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941218379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry K, Erice A, Tierney C, Balfour HH, Fischl MA, Kmack A, et al. A randomized, controlled, double-blind study comparing the survival benefit of four different reverse transcriptase inhibitor therapies (three-drug, two-drug, and alternating drug) for the treatment of advanced AIDS. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1998;19:339–349. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199812010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. AIDS and stigma. American Behavioral Scientist. 1999;42:1106–1116. [Google Scholar]

- HIV Trialists' Collaborative Group. Zidovudine, didanosine, and zalcitabine in the treatment of HIV infection: meta-analyses of the randomised evidence. Lancet. 1999;353:2014–2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WC, Pace JL. HIV-seropositive individuals' optimistic beliefs about prognosis and relation to medication and safe sex adherence. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17:677–683. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.00746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hydén LC. Illness and narrative. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1997;19:48–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kubler-Ross E. On Death and Dying. New York: Scribner; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RS, Kockman A, Sikkema KJ. Internalized stigma among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6:309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J, Jackson ED, Petitto JM, Golden RN, Silva SG, Perkins DO, Cai J, Folds JD, Evans DL. Progression to AIDS: The effects of stress, depression, and social support. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1999;61:397–406. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199905000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke TJ, Giordano TP, Rabeneck L. Utilization of health care resources by HIV-infected white, African American, and Hispanic men in the era before highly active antiretroviral therapy. 2003 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczo N. Beyond the “Fetishism of Words”: Considerations on the use of the interviews to gather chronic illness narratives. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13:469–490. doi: 10.1177/1049732302250756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder CL, Antoni MH, Duivenvoorden HJ, Kauffmann RH, Goodkin K. Active confrontational coping predicts decreased clinical progression over a one-year period in HIV-infected homosexual men. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1995;39:957–965. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narcotics Anonymous. Narcotics Anonymous, It Works: How and Why. World Service Conference 1987 [Google Scholar]

- Rice P, Ezzy D. Qualitative Research Methods: A Health Focus. Sydney: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Roth NL, Nelson MS. HIV diagnosis rituals and identity narratives. AIDS Care. 1997;9:161–179. doi: 10.1080/09540129750125190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg KH, Paskey S. The risk of domestic violence and women with HIV infection: Implications for partner notification, public policy, and the law. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:1569–1576. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.11.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ. Variations in perceived pain associated with emotional distress and social identity in AIDS. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2000;14:659–665. doi: 10.1089/10872910050206586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13:905–923. doi: 10.1177/1049732303253488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Mason HRC, Marks G, Ruiz MS, Reed D, Richardson JL. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:474–478. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. AIDS stigma as social terrorism. Newsletter of the Society for Applied Anthropology. 2003;15:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: Reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2003;17:423–441. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Scott G, Wilson S, Easton D, Weeks M. “War stories”: AIDS prevention and the street narratives of drugs users. Qualitative Health Research. 2001;11:589–611. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Weeks MR. The Hartford Model of AIDS practice/research collaboration. In: Trickett E, editor. Community Intervention and HIV/AIDS: Affecting the Commuity Context. London: Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sollitto S, Mehlman M, Youngner S, Lederman M. Should physicians withhold highly active antiretroviral therapies from HIV/AIDS patients who are thought to be poorly adherent to treatment? AIDS. 2001;15:153–159. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200101260-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded Theory in Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Troop M, Easterbrook P, Thornton S, Flynn R, Gazzard B, Catalan J. Reasons given by patients for ‘non-progression’ in HIV infection. AIDS Care. 1997;9:133–142. doi: 10.1080/09540129750125172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G. The genesis of chronic illness: Narrative reconstruction. Sociology of Health and Illness. 1984;6:175–200. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep10778250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]