Abstract

The voltage-gated Cl− channel (CLC) family comprises cell surface Cl− channels and intracellular Cl−/H+ exchangers. CLCs in organelle membranes are thought to assist acidification by providing a passive chloride conductance that electrically counterbalances H+ accumulation. Following recent descriptions of Cl−/H+ exchange activity in endosomal CLCs we have re-evaluated their role. We expressed human CLC-5 in HEK293 cells, recorded currents under a range of Cl− and H+ gradients by whole-cell patch clamp, and examined the contribution of CLC-5 to endosomal acidification using a targeted pH-sensitive fluorescent protein. We found that CLC-5 only conducted outward currents, corresponding to Cl− flux into the cytoplasm and H+ from the cytoplasm. Inward currents were never observed, despite the range of intracellular and extracellular Cl− concentrations and pH used. Endosomal acidification in HEK293 cells was prevented by 25 μm bafilomycin-A1, an inhibitor of vacuolar-type H+-ATPase (v-ATPase), which actively pumps H+ into the endosomal lumen. Overexpression of CLC-5 in HEK293 cells conferred an additional bafilomycin-insensitive component to endosomal acidification. This effect was abolished by making mutations in CLC-5 that remove H+ transport, which result in either no current (E268A) or bidirectional Cl− flux (E211A). Endosomal acidification in a proximal tubule cell line was partially sensitive to inhibition of v-ATPase by bafilomycin-A1. Furthermore, in the presence of bafilomycin-A1, acidification was significantly reduced and nearly fully ablated by partial and near-complete knockdown of endogenous CLC-5 by siRNA. These data suggest that CLC-5 is directly involved in endosomal acidification by exchanging endosomal Cl− for H+.

Introduction

Members of the mammalian CLC family of membrane proteins comprise cell surface Cl− channels (CLC-1, -2, -Ka, -Kb) and organelle Cl−/H+ exchangers (CLC-3 to -7) with varying degrees of outwardly, inwardly, or non-rectifying currents (reviewed in Jentsch et al. 2005). Loss of function of CLC family members is associated with a variety of inherited pathophysiological disorders including myotonia congenita (CLC-1), idiopathic epilepsy (CLC-2), Bartter syndrome (CLC-Kb), Dent's disease (CLC-5) and osteopetrosis (CLC-7) (reviewed in Jentsch et al. 2005).

CLC-5 is expressed in renal proximal tubule cells (Devuyst et al. 1999) where it co-localises with the vacuolar-type H+-ATPase (v-ATPase) in endosomal membranes (Günther et al. 1998). Coupled with the identification of CLC-5 as a member of the voltage-gated Cl− channel family, co-localisation of CLC-5 with v-ATPase led to the idea that CLC-5 provided the passive Cl− conductance required for maintaining the electroneutrality of organelles during acidification by v-ATPase (Sabolic & Burckhardt, 1986; van Dyke, 1988). The observed reduction in the rate and extent of endosomal acidification observed in CLC-5 knock-out mice (Günther et al. 2003; Hara-Chikuma et al. 2005) further strengthened the Cl− shunt hypothesis.

The discovery of voltage-dependent Cl−/H+ exchange activity in some CLC family members, including CLC-5 (Picollo & Pusch, 2005; Scheel et al. 2005), raised some doubts as to their suitability to fulfil the proposed role as an electrical shunt. Firstly, with an exchange stoichiometry of 2Cl−:1H+ (Zifarelli & Pusch, 2009) similar to the bacterial counterpart CLC-ec1 (Accardi & Miller, 2004), Cl− flux into the endosome would be coupled to a loss of half of the H+ transported into the endosome by the v-ATPase. Secondly, overexpression of cloned CLC-4 and CLC-5 give rise to outwardly rectifying currents that are active at positive potentials (Friedrich et al. 1999). When transposed to endosomal membranes, outward currents equate to the movement of positive charge (H+) into and negative charge (Cl−) out of the endosome. Recently, the outward rectification and pH sensitivity of CLC-3 currents expressed in the human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293 have been described (Matsuda et al. 2008). The Cl−/H+ exchange currents through CLC-3 are proposed to dissipate the build-up of negative charge due to endosomal NADPH oxidase activity by removing Cl− from the lumen, coupled with acidification that could potentially neutralise superoxide ions to produce H2O2 (Miller et al. 2007). In this model, the directions of Cl− and H+ flux are consistent with the outwardly rectifying currents.

Our first aim was to determine whether the voltage dependence or direction of CLC-5 current could be altered by changing the ionic gradients to result, in particular, in Cl− efflux. The endosomal concentrations of both Cl− and H+ vary over time (Hara-Chikuma et al. 2005) and the rectification of some ion channels, e.g. inwardly rectifying K+ channels, is modulated by increasing the concentration of permeant ions to relieve voltage-dependent pore blockade (Stanfield et al. 1994). We therefore studied the properties of ionic currents conducted by CLC-5 by expressing recombinant human CLC-5 in HEK293 cells using the whole-cell patch clamp technique, which enables control over the ionic environment on both sides of the membrane. Endosomal acidification and the direction of H+ flow through CLC-5 in endosomal membranes was also investigated using an endosome-targeted pH-sensitive green fluorescent protein (GFP) variant. We found that under all conditions tested CLC-5 only conducted outward currents when expressed in the plasma membrane, corresponding to Cl− influx and H+ efflux. We therefore hypothesised that CLC-5 might behave similarly in endosomal membranes and directly acidify endosomes independently of v-ATPase.

Methods

Molecular biology

Human CLC-5 was expressed as a full length protein (pCMV-CLC-5, a gift from Professor R. V. Thakker, University of Oxford) or with a C-terminal enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (CLC-5-EYFP) fusion protein or N-terminal haemagglutinin (HA-CLC-5) epitope tag (Smith et al. 2009). Mutations in CLC-5 were generated by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) and constructs were verified by automated DNA sequencing (Faculty of Biological Sciences facility, University of Leeds). Constructs expressing vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2)-fused or glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored ratiometric pHluorin were a gift from Professor G. Miesenböck (Oxford University), and a construct expressing CD8 membrane protein was from Dr M. Hunter (University of Leeds).

Electrophysiology

HEK293 cells (Griptite 293 MSR cell line, Invitrogen) were transiently transfected with CLC-5-EYFP using Fugene 6 (Roche) and transfected cells were identified by EYFP epifluorescence. To express unfused CLC-5, full-length CLC-5 was co-transfected with CD8 and transfected cells were identified using Dynabeads CD8 (Dynal Biotech). Patch pipettes were pulled from thin-walled borosilicate glass (Harvard Apparatus), polished, and gave resistances of 2–4 MΩ in experimental solutions. Currents were recorded at room temperature (20–22°C) by whole-cell patch clamp using an EPC-10 amplifier (HEKA Electronics) and >70% series resistance compensation where appropriate. Junction potentials were calculated using the calculator supplied with the pCLAMP 9.0 software (Axon Instruments) and the voltage offset was corrected prior to seal formation. Currents were filtered at 10 kHz and digitised at 50 kHz using PatchMaster software (HEKA Electronics). Cells were held at −30 mV and 10 ms pulses from −100 to +100 or +200 mV at 10 mV increments were applied at 1 s intervals. To evoke tail currents, cells were held at −30 mV and a 3 ms pulse to +200 mV was applied prior to the test pulses. P/–4 leak subtraction was used where appropriate and currents were divided by the whole-cell capacitance to give current density (pA pF−1).

The standard bath solution contained (in mm) 136 CsCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 Hepes, 5 Mes, pH 7.4 with CsOH. The standard pipette solution contained 42 CsCl, 98 aspartic acid, 10 EGTA, 5 Hepes, 5 Mes, pH 7.4 with CsOH. To vary [Cl−], CsCl was replaced by aspartic acid. The use of both Hepes and Mes enabled buffering over the pH range used in these studies.

The theoretical reversal potentials (Erev) in the various levels of pH and [Cl−] were calculated using the equation in Accardi & Miller (2004):

| (1) |

where ECl and EH are the Cl− and H+ equilibrium potentials, respectively, and r the ratio of H+ transported per Cl−. Using a transport ratio (r) of 0.5 (Zifarelli & Pusch, 2009), this equation can be expanded and rearranged (to log10) to give the theoretical Erev at room temperature with the various levels of [Cl−] and pH inside and outside the cell ([Cl−]i, [Cl−]o, pHi and pHo):

|

(2) |

The Boltzmann distribution, using the calculated reversal potential (Erev) to calculate conductance, was fitted to the current–voltage (I–V) relationships:

| (3) |

where Gmax is the maximum conductance, V1/2 the voltage that gives half-maximal activation, and k the slope factor. Alternatively, the current amplitudes were converted to conductance (G) by dividing by the driving force, V – Erev, and conductance–voltage relationships were fitted by Boltzmann distributions (eqn (4)), which were then normalised to Gmax to generate the mean activation curves.

| (4) |

Confocal microscopy

HEK293 cells were transfected with VAMP2-pHluorin plus wild-type or mutant HA-CLC-5 and seeded onto poly-l-lysine-coated borosilicate coverslips. HA-tagged protein was labelled and imaged as described previously (Mankouri et al. 2006). Briefly, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, permeabilised with 1:1 acetone/methanol (−20°C), and labelled with rat anti-HA antibody (Roche) diluted in 5% goat serum in PBS. Cells were then extensively washed and labelled with anti-rat Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted in 5% goat serum in PBS. Labelled cells were examined using a Zeiss LSM510-META laser scanning confocal microscope under an oil-immersed ×63 objective lens (NA = 1.40). pHluorin was excited using an argon laser fitted with 488 nm filters and Cy3 was excited using a He/Ne laser fitted with 543 nm filters. Images were analysed using a Zeiss LSM5 image browser.

Vesicular acidification measurement

The intra-luminal pH of endosomal compartments was determined using endosome-targeted ratiometric pHluorin as carried out previously (Smith et al. 2009). HEK293 and opossum kidney (OK) cells were transfected with ratiometric pHluorin and were imaged using a Zeiss LSM510-Meta laser scanning confocal microscope with an oil-immersed ×63 objective lens (NA = 1.40). The cells were bathed in imaging solution (in mm; 25 Na-Hepes (pH 7.4), 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 30 glucose) and examined at 37°C. Ratiometric pHluorin was excited at 405 nm using a diode laser and at 488 nm using an argon laser. Emitted fluorescence was collected through a 505 nm long-pass filter. The fluorescence intensity of ratiometric pHluorin with each excitation wavelength was measured from regions of interest using ImageJ software (NIH) and the 405 nm/488 nm fluorescence ratio calculated. GPI-anchored pHluorin, which adheres to the extracellular surface of the plasma membrane, was used to construct a pH versus 405 nm/488 nm fluorescence ratio calibration curve with both HEK293 and OK cells using bathing solutions adjusted to a range of pH. This method of calibrating pHluorin was validated by comparing in situ measurements of pHluorin fused to the N-terminus of mouse VAMP2, which was used to measure the pH of endosomes (see Supplemental data for this paper, available online only). The constructs and characterisation of pHluorin are described by Miesenböck et al. (1998). Bafilomicin-A1 (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared as a 25 mm stock solution in DMSO, which was subsequently diluted in the experimental solution to a final concentration of 25 μm.

Knockdown of OK cell CLC-5 using siRNA

Endogenous CLC-5 mRNA in opossum kidney (OK) cells, a renal proximal tubule cell line, was knocked down using siRNA targeted against the predicted opossum CLC-5 open reading frame (Genbank, XM_001363619). The siRNA duplexes were designed and manufactured by Eurogentec and were targeted against three separate mRNA sequences: 5′-GCACTTCCATCATTCATTT-3′ (siRNA1), 5′-GAGACCTCATCATTTCCAT-3′ (siRNA2), and 5′-GCTCTTCAATGACTGTGGT-3′ (siRNA3). In control experiments, cells were either mock transfected (no siRNA) or transfected with control siRNA (Silencer negative control no. 1 siRNA, Ambion). The siRNA duplexes were transfected into OK cells using X-tremeGENE reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and harvested for experiments 72 h later. The degree of CLC-5 mRNA knockdown was determined by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). RNA was extracted from OK cells using the SV total RNA isolation system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA (2 μg) was reverse-transcribed using Superscript III (Invitrogen). CLC-5 abundance in first strand cDNA was examined using the LightCycler II quantitative PCR system (Roche) and was amplified using primers 5′-GTGAGGGAGAAATCCAGA-3′ and 5′-TTGATGATCAGCGTCCA-3′. Expression was quantified relative to the abundance of opossum β-actin cDNA (Genbank XM_001372315), which was amplified using the primers 5′-TCATGAAGTGTGACGTTGACATCCGT-3′ and 5′-CCTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGCACGATG-3′. In each experiment (n= 4) the expression of CLC-5 relative to β-actin with each siRNA treatment was expressed relative to that in the control (mock transfected) cells. Protein concentrations in OK cell lysates were quantified and equal amounts were loaded and separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane and incubated with rabbit anti-CLCN5 (Prestige Antibodies, Sigma-Aldrich) or mouse anti-translocation-associated membrane protein 1 (TRAM1; Abcam). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were used (Jackson Immunoresearch) and detected by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ±s.e.m. of n cells or samples. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was tested using either Student's t test or ANOVA.

Results

Expression of CLC-5 in HEK293 cells gives large, outwardly rectifying currents

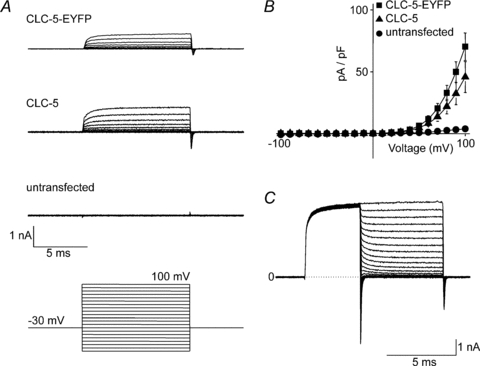

Human CLC-5, fused with EYFP at the C-terminus (CLC-5-EYFP), was expressed in HEK293 cells and whole-cell currents were examined by patch clamp electrophysiology. Caesium-based solutions were used to eliminate endogenous potassium currents. Macroscopic CLC-5 currents were activated by test potentials above +30 mV, exhibited rapid activation (<1 ms), and displayed strong outward rectification (Fig. 1A and B). Such currents were absent in untransfected cells (Fig. 1A and B). To confirm that fusing EYFP had no effect on the functional properties of CLC-5, currents were recorded from cells expressing unfused CLC-5. These currents also exhibited strong outward rectification (Fig. 1A) with a voltage dependence that was indistinguishable from CLC-5-EYFP (Fig. 1B). CLC-5 outward rectification was studied further by applying a strong depolarisation to +200 mV and then applying test pulses to between +200 and −200 mV (Fig. 1C). Sustained outward currents were observed with test pulses from +200 down to +30 mV. At more negative potentials, test pulses resulted in a transient (<0.5 ms) inward current that decayed rapidly to leave no significant current. These transient inward currents that are evoked by repolarisation do not relate to Cl− or H+ transport through pre-deactivated CLC-5: the apparent reversal potential of these tail currents is approximately +45 mV and is unrelated to ECl, −30 mV, or EH, 0 mV. These transient inward currents are capacitative and arise from the CLC-5 voltage-sensing mechanism (Smith & Lippiat, 2010). In summary, sustained CLC-5 currents were only observed under conditions that result in an outward current.

Figure 1. Properties of CLC-5 expressed in HEK293 cells.

A, whole-cell currents recorded from untransfected cells or those expressing CLC-5-EYFP or unfused CLC-5 as indicated. Cells were held at −30 mV and 10 ms test pulses were applied at 10 mV increments between −100 mV and +100 mV as shown by the voltage protocol below the representative traces. B, mean (±s.e.m., n= 6–7 cells) current density–voltage relationships of cells expressing CLC-5-EYFP or CLC-5 compared to untransfected HEK293 cells. C, tail currents were evoked by 3 ms pre-pulses to +200 mV followed by 5 ms test pulses from +200 mV to −200 mV at 10 mV increments. The dotted line denotes the zero current level (0).

Effects of altering intra- and extracellular [Cl−] on CLC-5 currents

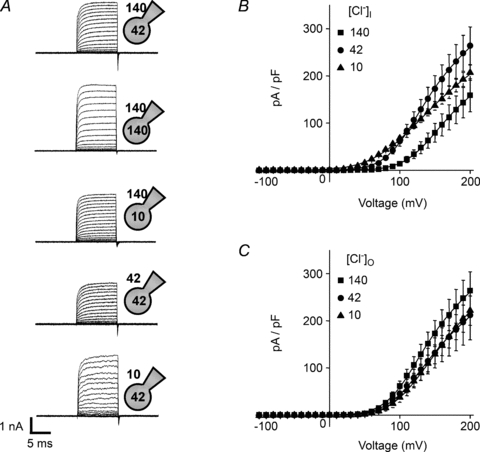

CLC-5 is proposed to facilitate endosomal acidification by permitting Cl− to enter the endosome and electrically balance the active pumping of H+ (Günther et al. 1998). Since this mechanism leads to changes in both endosomal pH and [Cl−] (Hara-Chikuma et al. 2005) the different ionic gradients experienced over time may influence CLC-5 gating. We therefore adjusted the pH and [Cl−] in the pipette (cytoplasmic) and bathing (equivalent to endosomal lumen) solutions and recorded whole-cell CLC-5 currents. The intracellular [Cl−] was changed to either 10 or 140 mm, whilst maintaining extracellular [Cl−] at 140 mm and all solutions at pH 7.4. In either case CLC-5 yielded currents that were qualitatively similar to those seen in the standard solutions (Fig. 2A) with respect to the current magnitude and the outward rectification (Fig. 2B). Despite the shifts of the current–voltage relationships along the voltage axis, neither condition induced inward currents. Similarly, outward whole-cell currents were observed when extracellular [Cl−] was reduced to 42 and 10 mm (Fig. 2A), but there was little change to the current–voltage relationship (Fig. 2C) and no evidence for inward current.

Figure 2. Effects of changing extracellular and intracellular [Cl−] on whole-cell CLC-5 currents.

Cells were held at −30 mV and 10 ms test pulses were applied at 10 mV increments to between −100 mV and +200 mV. A, representative current families recorded using the conditions indicated by the whole-cell patch clamp schematic diagrams denoting the intracellular and extracellular [Cl−] in mm. B, mean (±s.e.m., n= 7 cells) current density–voltage relationships using an extracellular solution containing 140 mm Cl− and varying the intracellular [Cl−], in mm as indicated in the key. C, mean (±s.e.m., n= 6–7 cells) current density–voltage relationships using an intracellular solution containing 42 mm Cl− and varying the extracellular [Cl−], in mm as indicated in the key. The continuous lines are Boltzmann functions (eqn (3)) fitted directly to the mean current density–voltage plots, using the predicted current reversal potential (eqn (2)).

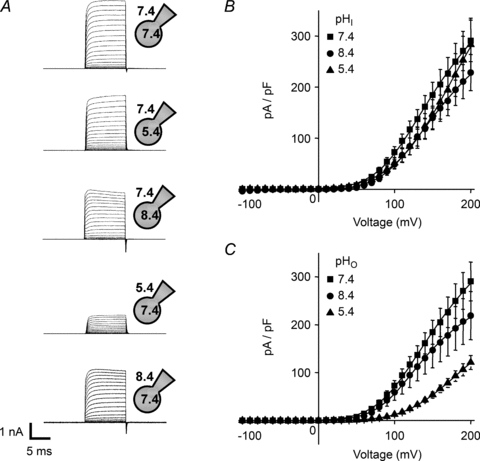

Effects of altering intra- and extracellular pH on CLC-5 currents

Using the standard bath and pipette solutions (140 mm[Cl−]o and 42 mm[Cl−]i), the intracellular pH was adjusted from 7.4 to either 5.4 or 8.4. Likewise, keeping intracellular pH at 7.4, the extracellular pH was adjusted to either 5.4 or 8.4. Again, currents were of a similar magnitude and exhibited strong outward rectification, being qualitatively similar to those observed with symmetrical pH 7.4 (Fig. 3A). Changing intracellular and extracellular pH caused small changes to the shape and position of the current–voltage relationships (Fig. 3B and C), but extracellular acidification to pH 5.4 reduced the amplitude of the CLC-5 currents (Fig. 3A and C) consistent with previous reports (Friedrich et al. 1999; Picollo & Pusch, 2005).

Figure 3. Effects of changing extracellular and intracellular pH on whole-cell CLC-5 currents.

Cells were held at −30 mV and 10 ms test pulses were applied at 10 mV increments to between −100 mV and +200 mV. A, representative current families from whole-cell recordings using conditions indicated by the whole-cell patch clamp schematic diagrams denoting the intracellular and extracellular pH as indicated. B, mean (±s.e.m., n= 6–7 cells) current density–voltage relationships when the extracellular solution had pH 7.4 and the intracellular pH was varied, as indicated. C, mean (±s.e.m., n= 6–7 cells) current density–voltage relationships when the intracellular solution had pH 7.4 and the extracellular pH was varied, as indicated. The continuous lines are Boltzmann functions (eqn (3)) fitted directly to the mean current density–voltage plots.

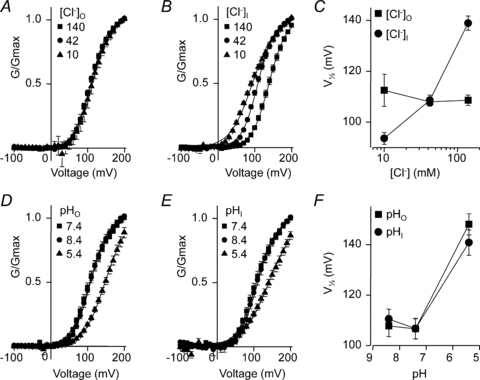

Effects of [Cl−] and pH on CLC-5 activation

The effects of altering extracellular and intracellular [Cl−] and pH on CLC-5 kinetics were analysed further by generating activation curves. Whilst CLC-5 is not a Cl− channel, but has Cl−/H+ exchange activity, it exhibits voltage-dependent activation. We envisaged that the conductance–voltage relationship would follow the Boltzmann function (eqn (4)), which describes voltage-dependent transitions. The strong rectification and rapid deactivation kinetics prevented measurement of the reversal potential of CLC-5 currents, therefore the theoretical reversal potentials (Erev, eqn (2)) were used to estimate the conductance (G). The conductance–voltage relationships and the shifts in the half-maximal activation voltages (V1/2) are shown in Fig. 4 with the calculated Erev and fitted parameters summarised in Table 1. The conductance–voltage relationships were well-fitted by the Boltzmann equation (eqn (4)) and reveal the effects of [Cl−] and pH on CLC-5 gating. With the 10–140 mm[Cl−] range, there was little effect of extracellular Cl−, but decreasing intracellular [Cl−] shifted CLC-5 activation to more negative potentials (Fig. 4A–C). Both the intracellular and extracellular low pH of 5.5 shifted activation to more positive potentials (Fig. 4D–F).

Figure 4. CLC-5 activation curves with the various extracellular and intracellular [Cl−] and pH.

The conductance G was calculated using the predicted reversal potential (eqn (2)), the Boltzmann function fitted to the conductance–voltage relationship, and data presented relative to the maximum conductance Gmax. A, mean (±s.e.m.) activation curves when the extracellular [Cl−] was varied, as indicated, in mm. The continuous lines are Boltzmann functions fitted to the mean data. B, mean activation curves when the intracellular [Cl−] was varied, as indicated. C, the mean (±s.e.m.) V1/2 values returned by the Boltzmann fits to the individual data sets plotted against extracellular and intracellular [Cl−]. Mean activation curves when the extracellular (D) and intracellular (E) pH were varied. F, mean activation V1/2 with the different extracellular and intracellular pH.

Table 1.

Effects of [Cl−] and pH on the predicted reversal potential, Erev (calculated from eqn (2)), and the activation kinetics (half-maximal activation voltage, V1/2, and the slope factor, k)

| [Cl−]o (mm) | [Cl−]i (mm) | pHo | pHi | Erev (mV) | V1/2 (mV) | k (mV) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 140 | 42 | 7.4 | 7.4 | −20.1 | 108.6 ± 2.0 | 22.0 ± 0.6 | 5 |

| 42 | 42 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 0 | 108.0 ± 1.7 | 22.5 ± 0.5 | 6 |

| 10 | 42 | 7.4 | 7.4 | +23.9 | 112.5 ± 6.3 | 22.3 ± 1.6 | 4 |

| 140 | 140 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 0 | 140.5 ± 2.9 | 24.3 ± 0.4 | 7 |

| 140 | 10 | 7.4 | 7.4 | −44.0 | 97.7 ± 2.8 | 35.8 ± 1.9 | 3 |

| 140 | 42 | 5.4 | 7.4 | +18.3 | 150.6 ± 3.0 | 34.4 ± 1.2 | 6 |

| 140 | 42 | 8.4 | 7.4 | −39.2 | 110.5 ± 4.6 | 25.3 ± 1.0 | 6 |

| 140 | 42 | 7.4 | 5.4 | −58.4 | 140.8 ± 5.0 | 35.6 ± 1.2 | 7 |

| 140 | 42 | 7.4 | 8.4 | −0.88 | 110.5 ± 3.9 | 24.0 ± 1.0 | 7 |

Importantly, CLC-5 was only active at positive potentials and inward currents were never observed under any of the conditions tested, including the large inward or outward concentration gradients of either [Cl−] or pH. The magnitudes of the currents at negative potentials (both raw data and leak-subtracted) were not significantly different between untransfected and CLC-5-expressing cells. The outward currents correspond to a flux of Cl− into the cytoplasm in exchange for H+ from the cytoplasm. Since CLC-5 is predominantly found in endosomal membranes we considered its function in these organelles by exploring its influence on endosomal acidification.

CLC-5 directly acidifies endosomal compartments in transfected HEK293 cells

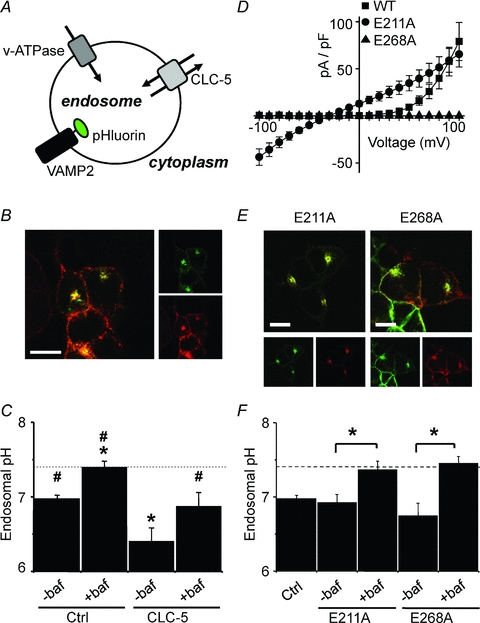

To examine the role of CLC-5 in endosomal acidification we used a pH-sensitive GFP variant, ratiometric pHluorin, fused to VAMP2 for endosomal targeting (Fig. 5A) (Miesenböck et al. 1998). This indicator has been used previously to examine pH changes in secretory vesicles and endosomes (Miesenböck et al. 1998; Disbrow et al. 2005) and to characterise endosomal acidification in HEK293 cells transfected with CLC-5 harbouring Dent's disease mutations (Smith et al. 2009). Figure 5B shows the overlapping distribution of pHluorin and CLC-5 in fixed HEK293 cells, both of which are localised in early and late endosomes (Smith et al. 2009); thus pHluorin reports the pH of CLC-5-containing endosomes.

Figure 5. Cl−/H+ exchange through CLC-5 enhances endosomal acidification.

A, endosomal pH, which is regulated by the activity of both v-ATPase and CLC-5, was measured using ratiometric pHluorin targeted to the luminal face of the endosomal membrane as a VAMP2-pHluorin fusion protein. B, confocal images showing VAMP2-pHluorin (green, upper inset image) and HA-CLC-5 (red, lower inset image) co-localised (yellow, main image) in fixed HEK293 cells (scale bar = 10 μm). C, endosomal pH (mean ±s.e.m., n > 20 cells) measured using VAMP2-pHluorin transfected into HEK293 cells alone (Ctrl) or with HA-CLC-5 (CLC-5). Where indicated (+baf), cells were treated with 25 μm bafilomycin-A1 for 1 h prior to and during the experiment to inhibit v-ATPase, or were untreated (–baf). The dotted line represents the pH of the bathing medium (pH 7.4). Statistical significance is shown with #P < 0.05 vs. CLC-5 (–baf), and *P < 0.05 vs. control (–baf) (ANOVA). D, current density–voltage relationships of whole-cell recordings from HEK293 cells expressing wild-type (WT), E211A, or E268A CLC-5-EYFP. Cells were held at −30 mV and 10 ms test pulses were applied at 10 mV increments between −100 mV and +100 mV. E, confocal images showing co-localisation (yellow, main images) of VAMP2-pHluorin (green, inset images) with either E211A or E268A mutant HA-CLC-5 (red, inset images) in fixed HEK293 cells (scale bar = 10 μm). F, endosomal acidification (mean ±s.e.m., n≥ 18 cells) in HEK293 cells transfected with VAMP2-pHluorin alone (Ctrl) or with either E211A or E268A mutant HA-CLC-5. Where indicated, cells were treated with 25 μm bafilomycin-A1 (+baf) for 1 h prior to and during the experiment to inhibit v-ATPase, or were untreated (–baf). The dashed line represents the pH of the bathing medium (pH 7.4). *P < 0.05 (Student's t test).

Endosomes from control HEK293 cells were more acidic (pH 6.98 ± 0.04, n= 32, P < 0.05) than the extracellular bathing pH of 7.4 (Fig. 5C). Endosomal acidification in untransfected HEK293 cells was abolished by treatment with 25 μm bafilomycin-A1, a selective inhibitor of v-ATPase (pH 7.40 ± 0.08, n= 31); this demonstrates complete inhibition of the v-ATPase by this concentration of bafilomycin-A1. Expression of wild-type CLC-5 in HEK293 cells led to an endosomal pH of 6.41 ± 0.17 (n= 24, Fig. 5C), significantly more acidic than the control HEK293 cells (P < 0.05). Treatment of CLC-5-expressing HEK293 cells with 25 μm bafilomycin-A1 resulted in an endosomal pH of 6.87 ± 0.18 (n= 25), which was significantly (P < 0.05) more acidic than the control untransfected HEK293 cells in the presence of bafilomycin-A1 and the bathing medium pH of 7.4. Overexpressing CLC-5 in HEK293 cells results in endosomal acidification by a mechanism independent of v-ATPase.

Another hypothesised role for CLC-5 involves the clustering and targeting of proteins involved in endocytosis and acidification (Hryciw et al. 2006b). In this sense CLC-5 plays a non-conducting role and serves to assist targeting of v-ATPase and NHE3 (Na+/H+-exchanger 3) to endosomal membranes (Moulin et al. 2003; Hryciw et al. 2006a). To confirm that the bafilomycin-insensitive acidification observed with the expression of CLC-5 in HEK293 cells was due to H+ conducted through CLC-5, we utilised two pore mutants that do not conduct H+. The first mutation, E211A, corresponds to the mutation of the ‘gating glutamate’ and ablates both H+ transport and voltage dependence (Friedrich et al. 1999; Picollo & Pusch, 2005; Scheel et al. 2005). This mutant conducts both outward and inward Cl− currents (Fig. 5D), has a linear current–voltage relationship that reverses at ECl (−30 mV), and would act as a Cl− shunt. The second mutation, E268A, is homologous to E203A in the prokaryotic isoform, CLC-ec1, which also removes H+ transport. This residue has been identified as the internal H+-acceptor site, or ‘proton glutamate’ of CLC-ec1 and is conserved only in the transporter subclass of the mammalian CLC family (Accardi et al. 2005). The E268A mutation in CLC-5, unlike the equivalent mutation in CLC-ec1, abolishes currents (Fig. 5D), an effect also observed by Zdebik et al. (2008). Both the E211A and E268A mutant CLC-5 co-localise with VAMP2-pHluorin in endosomes, similarly to wild-type CLC-5 (Fig. 5E). Endosomes in cells expressing either E211A or E268A acidified to pH 6.92 ± 0.11 (n= 20) and pH 6.74 ± 0.17 (n= 18), respectively, and are not significantly different from those measured from untransfected cells (Fig. 5F). Treatment of cells expressing either mutant with bafilomycin-A1 prevented acidification from the extracellular pH of 7.4 (pH 7.37 ± 0.12, n= 24, with E211A, and pH 7.45 ± 0.09, n= 29, with E268A). Neither E211A nor E268A CLC-5 proton transport mutants enhance endosomal acidification.

Bafilomycin-independent endosomal acidification in OK cells is conferred by endogenous CLC-5

We next sought to determine if CLC-5 found endogenously in proximal tubule cells (OK cells) functions in a similar manner. Using pHluorin, the pH of OK cell endosomes was 5.98 ± 0.05 (n= 22), which was more acidic than endosomal pH in HEK293 cells (Fig. 5C), but was only partially neutralised by 25 μm bafilomycin-A1 to 6.53 ± 0.12 (n= 23; Fig. 6C, mock transfected). OK cells were transfected with control siRNA and duplexes that were targeted to three different CLC-5 mRNA regions (siRNA1, siRNA2 and siRNA3). The control siRNA did not alter the CLC-5 mRNA abundance (1.05 ± 0.07, n= 4) relative to mock-transfected cells, but the CLC-5 siRNA partially or near-completely reduced CLC-5 mRNA. Using qRT-PCR, the abundance of CLC-5 mRNA was 0.60 ± 0.03, 0.57 ± 0.06 and 0.04 ± 0.01 with siRNA1, siRNA2 and siRNA3, respectively, relative to mock-transfected cells (all n= 4, Fig. 6A). Knockdown of OK cell CLC-5 mRNA resulted in reduced levels of CLC-5 protein (Fig. 6B). The endosomal pH of similarly treated cells was investigated by co-transfecting VAMP-pHluorin. Bafilomycin-A1 (25 μm) significantly (P < 0.05) reduced endosomal acidification in all cases (Fig. 6C). Knockdown of CLC-5 mRNA reduced both the total and the bafilomycin-insensitive acidification (Fig. 6C). The endosomal pH in the presence of 25 μm bafilomycin-A1 was 6.48 ± 0.10 (n= 21) with the control siRNA, which was not significantly different to mock-transfected cells (see above). The pH of bafilomycin-treated cells was significantly less acidic when treated with siRNA1 (7.00 ± 0.10, n= 21, P < 0.05), siRNA2 (7.05 ± 0.08, n= 21, P < 0.05), and siRNA3 (7.35 ± 0.06, n= 22, P < 0.05). With a combination of siRNA3 transfection and bafilomycin-A1 treatment, endosomal acidification was almost completely prevented. The data were plotted to show the relationship between the relative abundance of CLC-5 mRNA and endosomal acidification in the presence and absence of bafilomycin-A1 (Fig. 6D). The degree of acidification in OK cells in both the presence and absence of bafilomycin-A1 is related to the level of expression of endogenous CLC-5.

Figure 6. Effects of CLC-5 knockdown on endosomal acidification in OK cells.

OK cells were either mock transfected (M), transfected with control (C), or transfected with CLC-5-targeted siRNA1, -2 and -3 (s1, s2, s3, respectively). A, knockdown of endogenous CLC-5 in OK cells by siRNA determined by qRT-PCR 72 h post-transfection of CLC-5-targeted or control siRNA duplexes as indicated. The abundance of CLC-5 cDNA was normalised to that of β-actin and expressed relative to the ratio in mock transfected cells (mean ±s.e.m., n= 4 experiments). *P < 0.05 vs. mock-transfected cells. Products from the qRT-PCR reaction resolved by gel electrophoresis are shown below. B, reduced CLC-5 protein levels in similarly treated OK cells determined by Western blotting. Equal amounts of protein from OK cell lysates were loaded into each lane and proteins detected by anti-CLC-5 and anti-TRAM1 are shown in the top and bottom Western blot, respectively. Data are representative of three blots. C, endosomal pH (mean ±s.e.m., n≥ 16 cells) measured from OK cells that were treated as in A and co-transfected with VAMP2-pHluorin. Where indicated, cells were treated with 25 μm bafilomycin-A1 (+baf, filled bars) for 1 h prior to and during the experiment to inhibit v-ATPase, or were untreated (–baf, open bars). The dashed line represents the pH of the bathing medium (pH 7.4). *P < 0.05 –baf vs.+baf and #P < 0.05 vs. corresponding treatments in mock transfected cells. D, correlation between CLC-5 expression (from A) and endosomal acidification (from C) in bafilomycin-A1-treated (filled symbols) and untreated (open symbols) cells that were mock transfected (squares), or transfected with control (circles) or with siRNA1 (triangles), siRNA2 (inverted triangles), or siRNA3 (diamonds) CLC-5-targeted siRNA. The continuous fitted lines are second-order polynomials and the dashed line represents the pH of the bathing medium (pH 7.4).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify the physiological process mediated by CLC-5 in endosomal membranes. The functional properties identified to date, particularly voltage-dependent 2Cl−/H+ exchange, are not ideal for the anion shunt conductance required during endosomal acidification. Why would nature rely on CLC-5 to perform this role in epithelia when other CLCs, such as CLC-Ka or -Kb, could provide a passive Cl− conductance? Our approach was twofold: firstly to examine in more detail the biophysical properties of CLC-5 and secondly to investigate how CLC-5 contributes to endosomal acidification in conjunction with v-ATPase.

Under all experimental conditions tested, CLC-5 only conducted outward currents and activity was voltage dependent, being well-described by the Boltzmann function similar to voltage-gated ion channels. CLC-5 does not behave as a typical ion exchange transporter and does not appear to follow Michaelis–Menten kinetics: activity was not directly related to the availability of ionic substrate and transport was not reversible. Whilst the voltage-dependent mechanism is likely to have some similarities with the structurally related and outwardly rectifying Cl− channels, CLC-0 and CLC-1, there are some differences. These CLC Cl− channels are dependent on [Cl−]o (Pusch et al. 1995; Rychkov et al. 1996), but we found that changing [Cl−]o between 10 and 140 mm had no effect on CLC-5 activity (Fig. 4A and C). This lack of effect may be due to the obligate Cl−/H+ coupling in the pore, [Cl−]o could be saturating in this range, or the closed CLC-5 pore is relatively inaccessible to extracellular Cl−. In contrast, increasing [Cl−]i shifted CLC-5 voltage dependence to more positive potentials and lowering [Cl−]i had the opposite effect (Fig. 4B and C). Again this is unlike CLC-1 where [Cl−]i had no discernible effects (Rychkov et al. 1996), but is similar to the effects of [Cl−]i on the inwardly rectifying CLC-2 Cl− channel (Pusch et al. 1999). The inhibition of CLC-5 by lowering extracellular pH was caused by a reduction in both the driving force on the permeating ions and the activity of CLC-5. How lowering pH and intracellular [Cl−] modulates the voltage dependence of CLC-5 (Table 1) is presently unknown.

The outward CLC-5 currents correspond to Cl− flowing into the cytoplasm and H+ flowing out from the cytoplasm. These ionic fluxes are the opposite of those proposed for the shunt mechanism involving CLC-5 where Cl− is required to flow passively into the endosomal lumen. Instead, we detected the movement of H+ into endosomes through CLC-5 by measuring an enhanced acidification when CLC-5 was overexpressed in HEK293 cells (Fig. 5C) and a resultant bafilomycin-A1-insensitive component, indicating that it was independent of v-ATPase. The dependence of this process on the H+ transport activity of CLC-5 was confirmed by using the E211A and E268A mutants, where their expression did not result in v-ATPase-independent acidification (Fig. 5F). Cl− transport is retained in the E211A mutant and is bidirectional and voltage independent (Fig. 5D), and so would provide a shunt conductance, but this mutant had no effect on acidification. This lack of effect suggests that either v-ATPase activity is adequately shunted by an endogenous Cl− conductance or that expressed CLC-5 and VAMP2-pHluorin do not fully co-localise with v-ATPase. In addition, the failure of the non-conducting E268A CLC-5 mutant to alter acidification (Fig. 5D–F) suggests that CLC-5 protein interactions did not recruit other H+ transporting proteins to the endosomes in HEK293 cells. Alternatively, endosomal protein clustering caused by CLC-5 expression requires intact Cl−/H+ transport. CLC-5 has been found to be endogenously expressed in HEK293 cells (Devuyst et al. 1999), yet endosomal acidification was weak, relative to OK cells, and was completely inhibited by treatment with bafilomycin-A1 (Fig. 5C). The level of endogenous expression of CLC-5 in HEK293 cells may not be sufficient to enhance endosomal acidification or the protein may be resident in different vesicular compartments.

In our experiments with OK cells the endosomal pH was acidic by an order of magnitude (one pH unit) more than in HEK293 cells (Figs 5 and 6). It is possible that CLC-5 in its native environment can behave in a different manner or that functional CLC-5 can recruit proton-transporting proteins to endosomes to establish more effective endosomal acidification (Hryciw et al. 2006a). The reduction of both total and bafilomycin-insensitive acidification by siRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous CLC-5 mirrored the appearance of bafilomycin-insensitive acidification when CLC-5 was overexpressed in HEK293. The results with siRNA3, which gave the largest reduction in CLC-5 mRNA and protein in OK cells, raise some interesting points. In the near absence of CLC-5 the activity of v-ATPase alone results in reduced, but not ablated acidification, and is therefore adequately supported by a passive shunt conductance. These findings are consistent with endosomes isolated from CLC-5 knockout mice, which exhibit reduced, but cytosolic Cl−-dependent acidification (Günther et al. 2003).

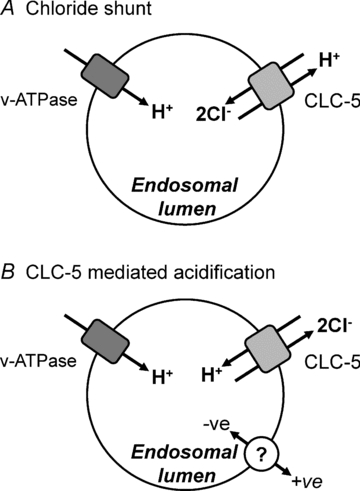

Our data suggest that native CLC-5 contributes to endosomal acidification by exchanging endosomal Cl− for cytoplasmic H+, as summarised in the schematic diagram in Fig. 7B. The Cl− concentration of newly formed endocytic vesicles is similar to that of the external medium but is rapidly (<1 min) reduced to approximately 20 mm by an interior-negative Donnan potential (Sonawane et al. 2002; Sonawane & Verkman, 2003). Negatively charged proteins at the cell surface have little effect on the large volume of the extracellular space but upon the formation of endocytic compartments they become concentrated into a significantly smaller volume. This is thought to lead to a negatively charged voltage relative to the cytoplasm, immediately upon endocytosis (Sonawane & Verkman, 2003; Saito et al. 2007). This may be sufficient to activate CLC-5 in the early endosome and drive Cl− extrusion (Saito et al. 2007), which would occur in exchange for H+ resulting in acidification of the early endocytic vesicles. This model provides no conducting role for CLC-5 following neutralisation of the interior-negative Donnan potential if CLC-5 is unable to conduct Cl− into the endosome. A rapid rate of acidification in early endocytic vesicles would contribute to effective and constitutive endocytosis in the proximal tubule. Acidification is required for both ligand–receptor dissociation and effective recycling of the multi-ligand receptor megalin back to the apical membrane, as discussed by Marshansky et al. (2002). The CLC-5-mediated component of early endosomal acidification would be absent in Dent's patients with loss-of-function mutations in CLC-5 and also in CLC-5 knockout mice.

Figure 7. Proposed roles of CLC-5 in endosomal acidification: Cl− shunt (A) versus direct acidification (B).

CLC-5 (light grey shape) and v-ATPase (dark grey shape) are depicted in the endosomal membrane. In A, two Cl− ions are transported into the vesicle lumen in exchange for a single proton. This provides an anion shunt for the pumping of protons into the endosome by v-ATPase since the 2Cl− to 1H+ gives a net influx of 3 negative charges. However, for every two H+ pumped into the endosome by v-ATPase, one is removed by CLC-5. In B, CLC-5 exchanges two Cl− ions from the endosomal lumen for a proton from the cytoplasm. This leads to endosomal acidification directly by CLC-5 and in parallel with v-ATPase. The compensatory shunt conductance is provided by an unidentified ion channel or transporter (open circle).

Our findings and proposed mechanism are at variance with the prevalent view that CLC-5 supports efficient acidification of endosomes by providing a Cl− conductance to counterbalance the accumulation of positively charged H+ pumped in by v-ATPase (Fig. 7A) (Günther et al. 1998). This role was proposed when CLC-5 was thought to be an ion channel through sequence homology with the well-studied CLC-0 and CLC-1 Cl− channels and prior to findings that CLC-5 has Cl−/H+ exchange activity (Picollo & Pusch, 2005; Scheel et al. 2005). The possibility that CLC-5 could directly acidify endosomes has been postulated previously (Scheel et al. 2005; Jentsch, 2007; Zifarelli & Pusch, 2009), but the data presented here are the first to directly demonstrate the ability of CLC-5 to acidify intracellular compartments independently of v-ATPase through its function as a Cl−/H+ exchanger. Much of the evidence in support of the Cl− shunt hypothesis has been derived from CLC-5 knockout mice. These have reduced endosomal acidification, consistent with the loss of a Cl− shunt, resulting in decreased v-ATPase function and endocytosis (Piwon et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2000; Günther et al. 2003; Hara-Chikuma et al. 2005). Alternatively, reduced acidification and endocytosis could arise from the loss of CLC-5-mediated H+ influx into the endosome. Many of the results described in these previous studies are unable to distinguish between defects in H+ transport into the endosome through either v-ATPase or CLC-5.

With endogenous CLC-5 directly acidifying early endosomes it would be expected that another channel or transporter would be required to provide a shunt conductance. Cl− accumulation in endosomes from proximal tubule cells of CLC-5 knockout mice is reduced, but acidification still requires cytosolic Cl− (Günther et al. 2003), which still enters the endosome (Hara-Chikuma et al. 2005), suggesting the existence of alternative pathways for Cl− entry, for which several candidates have been proposed. DIDS (4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid) and NPPB (5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)-benzoic acid)-sensitive 73 pS Cl− channels have been recorded from endosomal preparations from rat renal cortex (Schmid et al. 1989). Furthermore, CLIC1 is a Cl− channel that has been identified in subapical vesicles in proximal tubule cells and may be involved in endocytosis and recycling pathways (Ulmasov et al. 2007). Another candidate, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is found in the same subapical endosomes as CLC-5 in renal proximal tubules and disruption of CFTR function is associated with proteinuria in both cystic fibrosis patients and CFTR knockout mice (Jouret et al. 2007). Proteinuria occurs through a mechanism very similar to that observed in CLC-5 knockout mice, namely loss of multiligand receptors from the apical membrane and disruption of receptor-mediated endocytosis (Christensen et al. 2003; Jouret et al. 2007). The similarity between the phenotypes of mice lacking either CFTR or CLC-5 points towards their involvement in a common cellular process. It is likely that several channels and transporters provide the shunt conductance, possibly explaining the relatively moderate proteinuria phenotype observed in CFTR knockout mice (Jouret et al. 2007).

In summary, we have demonstrated that the outward rectification of the intracellular Cl−/H+ exchanger CLC-5 is a characteristic property of this transporter and that this translates into an ability to directly acidify endosomes independently of the v-ATPase. This process would be limited to the newly formed endocytic vesicle, where the transient interior-negative Donnan potential may drive extrusion of endocytosed Cl− through CLC-5 in exchange for H+. Efficient early acidification of endocytic vesicles might be an important step in constitutive endocytosis in the proximal tubule.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Rajesh Thakker (Oxford University) for the CLC-5 cDNA, Professor G. Miesenböck (Oxford University) for the pHluorin constructs and for helpful discussion on their use, and the following colleagues from the University of Leeds: Dr M. Hunter for the CD8 construct and anti-CD8 beads, Dr Gareth Howell for assistance with the pHluorin imaging, and Professor Asipu Sivaprasadarao and Dr Stan White for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 076545/Z/05/Z).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CLC

voltage-gated chloride channel

- EYFP

enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- HA

haemagglutinin

- HEK293

human embryonic kidney 293 cell line

- OK

opossum kidney

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- TRAM1

translocation-associated membrane protein 1

- v-ATPase

vacuolar-type H+-ATPase

- VAMP2

vesicle-associated membrane protein 2

Author contributions

A.J.S. and J.D.L. conceived and designed the experiments. All experiments were carried out by A.J.S. and J.D.L. at the University of Leeds. A.J.S. and J.D.L. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Author's present address

A. J. Smith: Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PT, UK.

Supplemental material

Supplemental information: Calibration of pHluorin measurements

Supplemental Methods

Supplemental Results

Supplemental Figure 1

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer-reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors

References

- Accardi A, Miller C. Secondary active transport mediated by a prokaryotic homologue of CLC Cl− channels. Nature. 2004;427:803–807. doi: 10.1038/nature02314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accardi A, Walden M, Nguitragool W, Jayaram H, Williams C, Miller C. Separate ion pathways in a Cl−/H+ exchanger. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:563–570. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen EI, Devuyst O, Dom G, Nielsen R, Van Der Smissen P, Verroust P, Leruth M, Guggino WB, Courtoy PJ. Loss of chloride channel ClC-5 impairs endocytosis by defective trafficking of megalin and cubilin in kidney proximal tubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8472–8477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432873100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devuyst O, Christie PT, Courtoy PJ, Beauwens R, Thakker RV. Intra-renal and subcellular distribution of the human chloride channel, CLC-5, reveals a pathophysiological basis for Dent's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:247–257. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disbrow GL, Hanover JA, Schlegel R. Endoplasmic reticulum-localized human papillomavirus type 16 E5 protein alters endosomal pH but not trans-Golgi pH. J Virol. 2005;79:5839–5846. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5839-5846.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich T, Breiderhoff T, Jentsch TJ. Mutational analysis demonstrates that ClC-4 and ClC-5 directly mediate plasma membrane currents. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:896–902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günther W, Lüchow A, Cluzeaud F, Vandewalle A, Jentsch TJ. ClC-5, the chloride channel mutated in Dent's disease, colocalizes with the proton pump in endocytotically active kidney cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8075–8080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günther W, Piwon N, Jentsch TJ. The ClC-5 chloride channel knock-out mouse – an animal model for Dent's disease. Pflugers Arch. 2003;445:456–462. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0950-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara-Chikuma M, Wang Y, Guggino SE, Guggino WB, Verkman AS. Impaired acidification in early endosomes of ClC-5 deficient proximal tubule. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;329:941–946. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hryciw DH, Ekberg J, Ferguson C, Lee A, Wang D, Parton RG, Pollock CA, Yun CC, Poronnik P. Regulation of albumin endocytosis by PSD95/Dlg/ZO-1 (PDZ) scaffolds. Interaction of Na+–H+ exchange regulatory factor-2 with ClC-5. J Biol Chem. 2006a;281:16068–16077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hryciw DH, Ekberg J, Pollock CA, Poronnik P. ClC-5: a chloride channel with multiple roles in renal tubular albumin uptake. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006b;38:1036–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch TJ. Chloride and the endosomal–lysosomal pathway: emerging roles of CLC chloride transporters. J Physiol. 2007;578:633–640. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch TJ, Neagoe I, Scheel O. CLC chloride channels and transporters. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouret F, Bernard A, Hermans C, Dom G, Terryn S, Leal T, Lebecque P, Cassiman JJ, Scholte BJ, de Jonge HR, Courtoy PJ, Devuyst O. Cystic fibrosis is associated with a defect in apical receptor-mediated endocytosis in mouse and human kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:707–718. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankouri J, Taneja TK, Smith AJ, Ponnambalam S, Sivaprasadarao A. Kir6.2 mutations causing neonatal diabetes prevent endocytosis of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. EMBO J. 2006;25:4142–4151. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshansky V, Ausiello DA, Brown D. Physiological importance of endosomal acidification: potential role in proximal tubulopathies. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2002;11:527–537. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda JJ, Filali MS, Volk KA, Collins MM, Moreland JG, Lamb FS. Overexpression of CLC-3 in HEK293T cells yields novel currents that are pH dependent. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C251–C262. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00338.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesenböck G, De Angelis DA, Rothman JE. Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent proteins. Nature. 1998;394:192–195. doi: 10.1038/28190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller FJ, Jr, Filali M, Huss GJ, Stanic B, Chamseddine A, Barna TJ, Lamb FS. Cytokine activation of nuclear factor κB in vascular smooth muscle cells requires signaling endosomes containing Nox1 and CLC-3. Circ Res. 2007;101:663–671. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.151076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulin P, Igarashi T, Van Der Smissen P, Cosyns JP, Verroust P, Thakker RV, Scheinman SJ, Courtoy PJ, Devuyst O. Altered polarity and expression of H+-ATPase without ultrastructural changes in kidneys of Dent's disease patients. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1285–1295. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picollo A, Pusch M. Chloride/proton antiporter activity of mammalian CLC proteins ClC-4 and ClC-5. Nature. 2005;436:420–423. doi: 10.1038/nature03720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwon N, Günther W, Schwake M, Bosl MR, Jentsch TJ. ClC-5 Cl− channel disruption impairs endocytosis in a mouse model for Dent's disease. Nature. 2000;408:369–373. doi: 10.1038/35042597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusch M, Jordt SE, Stein V, Jentsch TJ. Chloride dependence of hyperpolarization-activated chloride channel gates. J Physiol. 1999;515:341–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.341ac.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusch M, Ludewig U, Rehfeldt A, Jentsch TJ. Gating of the voltage-dependent chloride channel CIC-0 by the permeant anion. Nature. 1995;373:527–531. doi: 10.1038/373527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rychkov GY, Pusch M, Astill DS, Roberts ML, Jentsch TJ, Bretag AH. Concentration and pH dependence of skeletal muscle chloride channel ClC-1. J Physiol. 1996;497:423–435. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabolic I, Burckhardt G. Characteristics of the proton pump in rat renal cortical endocytotic vesicles. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1986;250:F817–F826. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1986.250.5.F817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Hanson PI, Schlesinger P. Luminal chloride-dependent activation of endosome calcium channels: patch clamp study of enlarged endosomes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27327–27333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheel O, Zdebik AA, Lourdel S, Jentsch TJ. Voltage-dependent electrogenic chloride/proton exchange by endosomal CLC proteins. Nature. 2005;436:424–427. doi: 10.1038/nature03860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid A, Burckhardt G, Gögelein H. Single chloride channels in endosomal vesicle preparations from rat kidney cortex. J Membr Biol. 1989;111:265–275. doi: 10.1007/BF01871011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AJ, Lippiat JD. Voltage-dependent charge movement associated with activation of the CLC-5 2Cl−/1H+ exchanger. FASEB J. 2010 doi: 10.1096/fj.09-150649. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AJ, Reed AA, Loh NY, Thakker RV, Lippiat JD. Characterization of Dent's disease mutations of CLC-5 reveals a correlation between functional and cell biological consequences and protein structure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F390–F397. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90526.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonawane ND, Thiagarajah JR, Verkman AS. Chloride concentration in endosomes measured using a ratioable fluorescent Cl− indicator: evidence for chloride accumulation during acidification. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5506–5513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110818200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonawane ND, Verkman AS. Determinants of [Cl−] in recycling and late endosomes and Golgi complex measured using fluorescent ligands. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:1129–1138. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanfield PR, Davies NW, Shelton PA, Khan IA, Brammar WJ, Standen NB, Conley EC. The intrinsic gating of inward rectifier K+ channels expressed from the murine IRK1 gene depends on voltage, K+ and Mg2+ J Physiol. 1994;475:1–7. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov B, Bruno J, Woost PG, Edwards JC. Tissue and subcellular distribution of CLIC1. BMC Cell Biol. 2007;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke RW. Proton pump-generated electrochemical gradients in rat liver multivesicular bodies. Quantitation and effects of chloride. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:2603–2611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SS, Devuyst O, Courtoy PJ, Wang XT, Wang H, Wang Y, Thakker RV, Guggino S, Guggino WB. Mice lacking renal chloride channel, CLC-5, are a model for Dent's disease, a nephrolithiasis disorder associated with defective receptor-mediated endocytosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2937–2945. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.20.2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdebik AA, Zifarelli G, Bergsdorf EY, Soliani P, Scheel O, Jentsch TJ, Pusch M. Determinants of anion–proton coupling in mammalian endosomal CLC proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4219–4227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708368200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zifarelli G, Pusch M. Conversion of the 2 Cl−/1 H+ antiporter ClC-5 in a NO3−/H+ antiporter by a single point mutation. EMBO J. 2009;10:1111–1116. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.