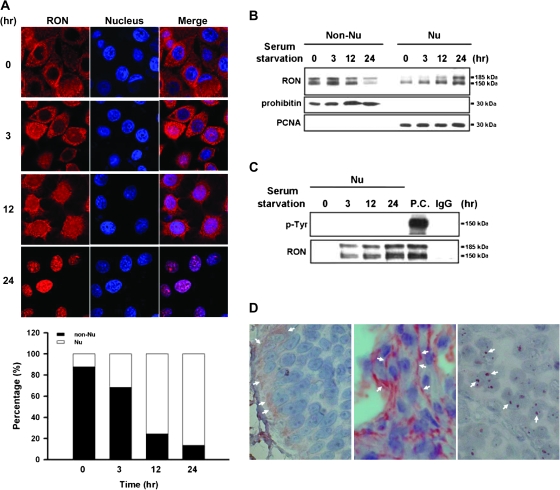

Fig. 1.

Kinetic analysis of nuclear localization of RON. TSGH8301 cells were serum starved for different time periods from 0, 3, 12 to 24 h. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis was conducted to monitor the time-dependent nuclear localization of RON. Treated cells were incubated with anti-RON (red) and then a Rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody (upper panel). Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). The purple signals (merged) highlight the localization of RON in the nucleus. The results were quantified and expressed as a histogram (bottom panel). (B) Western blotting with anti-RON antibody on subcellular fractions of treated cells was exhibited to determine time-dependent nuclear import of RON. The prohibitin and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) were chosen as markers for non-nucleus and nucleus fractions, respectively. (C) Nuclear fractions from treated cells were subjected to co-immunoprecipitation analysis with anti-RON antibody and then probed with anti-tyrosine (p-Tyr) antibody. Total cell lysate with MSP treatment was used as positive control (P.C.) for phospho-RON staining, and IgG was used as negative control of immunoprecipitation assay. (D) Immunohistochemical analysis was performed to detect RON expression on human bladder tissues from bladder cancer patients (n = 73). In this representative example, white arrows indicate positive staining areas of RON. Both ‘right’ and ‘middle panels’ are malignant bladder tissues; the ‘left panel’ is normal bladder tissue.