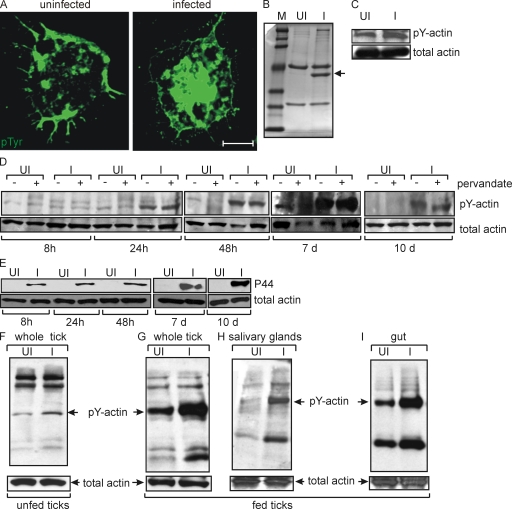

Figure 1.

A. phagocytophilum induces actin phosphorylation in tick cells and ticks. (A) Immunofluorescence images of uninfected and A. phagocytophilum–infected tick cells at 48 h after infection, stained for phosphotyrosine (pTyr). Bar, 10 µm. Representative images are shown from three independent experiments. (B) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE image of anti-pTyr immunoprecipitated proteins from uninfected (UI) and A. phagocytophilum-infected (I) lysates at 48 h after infection. The arrow denotes the dominant phosphorylated band identified as actin in A. phagocytophilum–infected cells. Phosphorylation of a protein with a higher molecular mass was also noted. (C) Lysates with (I) or without (UI) A. phagocytophilum were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against pTyr and probed with antibodies against actin. The level of actin before immunoprecipitation (total actin) served as the loading control. (D) Lysates from cells infected (I) or not (UI) with A. phagocytophilum were isolated at different time points (8, 24, and 48 h and 7 and 10 d) and assessed for actin phosphorylation in the presence (+) or absence (−) of pervanadate, a protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor. (E) The presence of A. phagocytophilum in infected tick cells was assessed by immunoblotting with antisera specific for the A. phagocytophilum P44 antigen (P44). Actin served as loading control. (F) Lysates were prepared from unfed ticks infected (I) or not (UI) with A. phagocytophilum. 20 µg of total lysates were probed with pTyr-specific antibody. pY-actin is denoted by an arrow. Total actin served as loading control. Whole tick (G), salivary gland (H), and gut tissue (I) lysates were prepared from I. scapularis fed for 48 h on uninfected or A. phagocytophilum–infected mice and were analyzed as described in F. Representative data are shown from three independent experiments in all panels.