Abstract

Background

Biased attention for emotional stimuli reflects vulnerability or resilience to emotional disorders. The current study examines whether the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism is associated with attentional biases for negative word stimuli.

Method

Unmedicated, young adults with low current depression and anxiety symptoms (N = 106) were genotyped for the 5-HTTLPR, including the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs25531 in the long allele of the 5-HTTLPR. Participants then completed a standard dot-probe task that measured attentional bias toward anxiety, dysphoric, and self-esteem words.

Results

The LALA allele group demonstrated an attentional bias away from negative word stimuli. This attentional bias was absent among the S/LG carriers.

Conclusions

These findings replicate previous work and suggest that 5-HTTLPR LA homozygotes possess a protective attentional bias that may decrease susceptibility to depression and anxiety.

Keywords: serotonin transporter gene, anxiety, depression, 5-HTTLPR polymorphism, attention

INRODUCTION

Cognitive models of depression and anxiety emphasize that biased attention for emotional stimuli can influence vulnerability or resilience to emotional disorders, such as depression and anxiety (1). Biased attention toward negative information can be detrimental to adaptive self-regulation (2) and is associated with clinical diagnosis of depression (3) and anxiety (4, 5, 6). On the other hand, the absence of a negative bias is associated with enhanced resiliency to stress and lower levels of anxiety (7). Similarly, longitudinal studies show that biased attention to negative information combines with life stress to predict increases in depressive symptoms, even when controlling for depression history (8). Indeed, biased processing of negative stimuli is a better predictor of future emotional and cortisol reactivity to laboratory and naturally occurring stressors than neuroticism, trait-anxiety, and extraversion (9). Even more compelling, experimentally inducing biased attention to negative information can cause increased vulnerability to sad and anxious affect (6, 10).

Emerging evidence suggests that genetic variation may foster a negativity bias; specifically, a variable repeat sequence in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR; see 11 for a review). The serotonin transporter (5-HTT) refreshes the synaptic cleft by removing serotonin. Consequently, the transporter is responsible for decreasing the amount of serotonin in both the synapse and extracellular space. The function of the serotonin transporter is degraded among carriers of the short 5-HTTLPR allele (12, 13). As a result, carriers of the short 5-HTTLPR allele have increased levels of extracellular serotonin and increased serotonin signaling compared with those who have two long alleles. Carriers of short 5-HTTLPR alleles have significantly reduced gray matter volume in the perigenual anterior cingulate (pACC) and the rostral anterior cingulate, both of which are involved in regulating affective information (14, 15). Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) analyses also suggested that short 5-HTTLPR allele carriers have decreased functional coupling between the pACC and the amygdala. As a result, carriers of the short allele experience heightened reactivity of the amygdala in response to negative emotional stimuli, such as negative pictures (16), fearful and angry faces (16, 17,19), and negative words (20).

To date, few behavioral studies have directly investigated the relationship between the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and biased attention. The first study to do so (21) sampled 27 psychiatric inpatients and found that carriers of the short 5-HTTLPR allele demonstrated biased attention toward anxiety-related words (e.g., scared, attack) relative to those homozygous for the long allele. More recently, studies have observed attentional bias in healthy populations (22, 23). Beevers and colleagues (22) found that carriers of the short 5-HTTLPR allele had greater difficulty disengaging from positive and negative stimuli compared to those homozygous for the long alleles. Fox and colleagues (23) further found that long 5-HTTLPR allele homozygotes were biased away from negative stimuli and toward positive stimuli. Finally, Pérez-Edgar and colleagues (24) found a linear relationship between the number of short 5-HTTLPR alleles and attentional bias for valenced faces in adolescents. Short 5-HTTLPR allele homozygotes were biased toward angry faces, while those homozygous for the long allele were biased toward happy faces.

The current study seeks to replicate and extend earlier findings by manipulating word content rather than valenced pictures or face stimuli (cf. 25). Using different word conditions allows us to determine whether attentional biases associated with the 5-HTTLPR are specific to certain word categories (e.g., anxiety, self-esteem) or whether attention is biased for negative stimuli in general. Additionally, we also examined the triallelic 5-HTTLPR variation [i.e., deletion polymorphism and rs25531] as only two previous studies in this research area (22, 24) have accounted for this variation. Genotyping the rs25531 SNP may provide a more accurate analysis of the association between the 5-HHLPR polymorphism and negativity bias than previous research because the LG variant of rs25531 and the S 5-HTTLPR allele are similar in function; thus only the LA variant is considered high expressing (26).

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Participants

One hundred and twenty-nine undergraduates from The University of Texas (84 female, 39 male, 6 unknown) volunteered in the study for partial class credit. Participant age ranged from 17 to 47 years (M = 19.5, SD = 3.10). After being introduced to a study of personality assessment, participants took part in a dot-probe task, completed questionnaire assessments of depression symptoms (27), anxiety symptoms (28), and neuroticism (29), and provided a saliva sample. Genetic information could not be extracted for 3 participants. Additionally, the nine participants who reported suspicion about the dot probe task and 11 dysphoric participants (BDI-SF > 9; 30) were excluded from the analysis. This left 106 participants in the final analysis. The internal review board at The University of Texas approved all procedures.

Materials

Dot-probe task

Word stimuli were taken from lists of affective words that were pretested and developed for use in dot probe tasks (31, 32). We matched each word pair for word length as well as frequency of use in the English language. Trials used 20 anxious-neutral (e.g., scared-salad) word pairs, 20 dysphoric-neutral (doom-palm) word pairs, 20 self-esteem-neutral (loser-ladder) word pairs, and 20 neutral-neutral word pairs.

The block of 80 word pairs was presented twice for a total of 160 trials. Each block of 80 word pairs was fully randomized for each participant. Each trial consisted of a white fixation cross on a black background in the middle of the screen for 500 ms, followed by a word pair presented for 500 ms. Word stimuli appeared in the top and bottom halves of the screen. Following the offset of the words, a small white asterisk probe on a black background appeared in the location of one of the words and remained on the screen until the participant responded with a key press on a standard keyboard. The computer recorded the latency and accuracy of each response. Each type of word stimulus (emotional or neutral) and the probe appeared in the top and bottom position with equal frequency.

Participants sat approximately 60 cm from a 15 inch computer monitor. Each stimulus word was approximately 1 cm (0.95° visual angle) high and the word pairs were spaced approximately 3.7 cm (3.5° visual angle) apart. Participants were told that their goal was to locate the position of the asterisk (“top” or “bottom”) as quickly and accurately as possible. They used their left index finger to press the “R” key when the asterisk appeared in the location of the top word and their right index finger to press the “N” key when the asterisk appeared in the location of the bottom word. Participants completed 10 practice trials using non-word pairs and repeated the practice until they responded accurately to at least 8 of the 10 practice trials.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA were isolated from buccal cells using a modification of published methods (33,34,35,36). The primer sequences are: forward, 5'-GGCGTTGCCGCTCTGAATGC-3' (fluorescently labeled), and reverse, 5'-GAGGGACTGAGCTGGACAACCAC-3'. These primer sequences yield products of 484 or 528 bp. Two investigators scored allele sizes independently and inconsistencies were reviewed and rerun when necessary. The frequency of the 5-HTTLPR genotypes (SS, n = 24 (22.7%); SL, n = 47 (44.3%); LL, n = 35 (33.0%)) did not differ from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, χ2 = 1.14, p = 0.29.

To distinguish between the S, LA, and LG fragments, the PCR fragment was digested with MspI according to the methods found in Wigg et al. (37). The resulting polymorphic fragments were separated using an ABI 3130XL DNA sequencer (S: 297, 127, 62 bp, LA: 340, 127, and 62 bp, LG: 174, 166, 127, and 62 bp). Allele frequencies were S: n = 95 (44.8%), LA: n = 101 (47.6%), LG: n = 16 (7.6%). Genotype distribution for the A/G SNP was in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, χ2 = 2.40, p = .12. Consistent with previous research, the S and LG alleles were designated S' and the LA allele was designated L'. We formed three groups: (a) S'S' (i.e., SS: n = 24 (22.6%), SLG: n = 6 (5.6%), LGLG: n = 2 (1.9%)), (b) S'L' (i.e., SLA: n = 41 (38.7%), LGLA: n = 6 (5.7%)), and (c) L'L' (i.e., LALA: n = 27 (25.5%)).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Descriptive statistics by 5-HTTLPR genotype group are described in Table 1. There were no significant differences as a function of genotype grouping for age, F(2,100) = .434, p = .65; gender, χ2(2, N = 102) = .440, p = .80; depressive symptoms, F(2,103) = 1.59, p = .21; anxiety symptoms, F(2,103) = .647, p = .53; and neuroticism, F(2,103) = .664, p = .52. Although there was a significant genotype frequency difference as a function race, χ2 (2, N = 105) = 9.11, p < .05, the 5-HTTLPR effect on attentional bias for negative stimuli was similar for Caucasians, F(2,53) = 3.19, p = .05, and non-Caucasians, F(2,38) = 3.75, p = .03, so we combined groups.

Table 1.

Demographics presented by 5-HTTLPR genotypea.

| L'L' Allele (n = 27) | S'L' Allele (n = 47) | S'S' Allele (n = 32) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | No. | M | SD | No. | M | SD | No. |

| Age (years) | 19.70 | 5.51 | 19.02 | 1.42 | 19.35 | 1.14 | |||

| Gender (men/women) | 9/18 | 16/28 | 9/22 | ||||||

| Race (Caucasian/other) | 21/5 | 22/25 | 15/17 | ||||||

| BDI-SF | 2.40 | 2.10 | 2.85 | 2.17 | 3.40 | 2.20 | |||

| BAI | 6.72 | 6.38 | 6.13 | 4.43 | 7.35 | 5.76 | |||

| Neuroticism | 2.40 | .571 | 2.57 | .652 | 2.52 | .543 | |||

Gender and race information were missing from 4 participants.

Important to note is that the short form of the BDI (BDI-SF) was used to measure depressive symptoms. The BDI-SF contains 13 items and the scores range from 0–39. The BDI-SF score for our sample was marginally significantly lower than that of the general college population (30; t (255.59) = 1.76, p = .07), and our sample scored significantly lower on the BAI than the general college population (38; t(167.40) = 3.99, p = .00). Given that we selected participants with low depression symptoms for the current study (because we did not want to confound symptoms with genetic variation), it is not surprising that our sample had lower levels of depression and anxiety than a general student population. Further, this also likely accounts for why 5-HTTLPR allele groups did not significantly differ for anxiety, depression, and neuroticism.

Data reduction

We analyzed response latencies only from correct responses. Eliminating incorrect responses resulted in a loss of less than 1% of data. In addition, to minimize the influence of outliers, we eliminated response latencies for each participant that were faster than 150 ms or slower than 1000ms. This resulted in a loss of less than 1% of the data.

Bias scores

Consistent with previous research (e.g., 39), attentional bias scores were calculated for each participant using the following equation:

| (1) |

where T = top position, B = bottom position, p = probe, and e = emotional word stimulus. Therefore, TpBe indicates the mean response latency when the probe is in the top position and the emotional word stimulus is in the bottom position, and so on. Positive bias scores indicate a bias toward the emotional stimuli while negative bias scores indicate a bias away from the emotional stimuli.

Main results

A 3 (word type: anxiety, dysphoria, self-esteem) × 3 (genotype status: S'S', S'L', L'L') repeated-measures ANOVA examined whether genetic status was differentially related to biased attention for anxious, dysphoric, and self-esteem stimuli. Results indicated a significant between-subjects effect for genetic group, F(2,95) = 3.75, p < .05, η2 = .07. None of the other main effects and interactions reached statistical significance: word type, F(2,190) = .07, p = .93, η2 = .00; and genetic group × word type, F(4,190) = 1.68, p = .16, η2 = .03. A very similar 5-HTTLPR effect was observed when using the bi-allelic classification (i.e., not accounting for the rs25531 SNP in L allele), F(2,95) = 4.12, p < .05, η2 = .08.

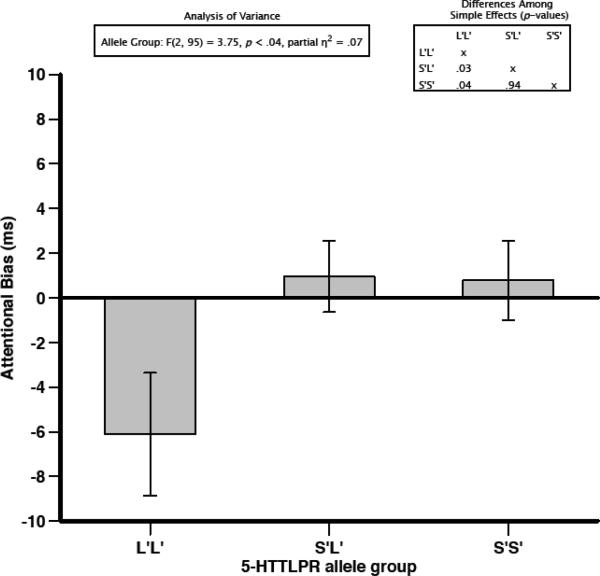

To follow-up the significant 5-HTTLPR main effect, we collapsed the dysphoria, anxiety, and self-esteem word scores into a single variable. The S'L' group (M = .96, SD = 10.40) did not significantly differ from the S'S' group (M = .78, SD= 9.52) in attentional bias toward negative words, t(69) = .07, p = .94. Neither the S'S' group nor the S'L' group evidenced an attentional bias score significantly different from zero, t(28) = .44, p = .66, and t(41) = .60, p = .55, respectively. However, the L'L' group (M = −6.11, SD = 14.28) evidenced a significantly greater bias away from negative word stimuli compared to the S'L' group, t(43.55) = −2.22, p < .05, and the S'S' group, t(44.86) = −2.11, p < .05 (see Figure 1). Furthermore, the L'L' group showed a bias away from negative word stimuli that was significantly different from zero, t(26) = −2.22, p < .05.

Figure 1.

Mean attentional bias scores (in milliseconds) across allele groups for the serotonin transporter promoter region polymorphism (5-HTTLPR). Error bars reflect standard error of the mean.

DISCUSSION

The current study examined associations between variants of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and attentional biases for negative word stimuli. While the bias toward negative words did not achieve significance for those with S/LG alleles, participants homozygous for the LA allele demonstrated a significant bias away from negative words. This bias was not specific to a particular type of negative stimuli; rather, a similar bias was observed for all three types of negative words (i.e., anxiety, dysphoric, or self-esteem words).

Findings provide an independent replication of Fox et al. (23), who also documented that long 5-HTTLPR allele homozygotes displayed biased attention away from negative images. We believe this replication is significant for several reasons. First, initial behavioral genetic findings are not often replicated (25). This has been particularly problematic in some areas, including research involving the 5-HTTLPR (40). Replication is necessary to ensure that initial findings are not due to random or Type I error (see 41). Second, it is notable that intermediate phenotypes, such as amygdala reactivity (42) and biased attention for emotion stimuli, appear to have a more consistent association with the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism than clinical outcomes, such as Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Connecting individual differences in intermediate phenotypes to the onset of complex psychiatric conditions represents an important next step for this research. Finally, this study replicates previous findings while accounting for the newly discovered rs25531 SNP in the L 5-HTTLPR allele. Accounting for the LA/LG variant may provide a cleaner and more accurate analysis of the relationship between the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and attentional biases (cf. 22,24).

If indeed the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism is partly responsible for a bias toward or away from negative stimuli, this could inform research and treatment on psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression. Insofar as preferential attention to negative stimuli can trigger and maintain anxiety and depression, the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism may protect some people against psychopathology. Future research should investigate whether the 5-HTTLPR interacts with biased attention to predict severity of depression and anxiety in samples experiencing a wider range of symptoms than in the current study. Further, inducing attentional biases toward aversive information can foster both anxiety and depressive symptoms following a stressful task (6) and training attention away from emotion stimuli leads to symptom improvement (43,44,45). Future research should examine whether the 5-HTTLPR moderates the effect of attention training on depression and anxiety symptoms. Doing so may identify which individuals are most likely to benefit from attention training interventions.

Limitations of our study include a limited genetic analysis, as other polymorphisms also likely contribute to biased attention, and unmeasured third variables (e.g., a functional genetic marker in linkage with the 5-HTTLPR promoter polymorphism) could account for our findings. We also did not include positive word stimuli, which would have helped to further document the specificity of biased attention for affective stimuli associated with the 5-HTTLPR. Nevertheless, this study contributes to the growing literature documenting that the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism is associated with biased attention for negative stimuli. By examining risk mechanisms across genetic, cognitive, and behavioral levels of analyses, we hope this study will also facilitate the development of more comprehensive explanatory models of vulnerability to psychopathology.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Preparation of this article was facilitated by a grant (R01MH076897) from the National Institute of Mental Health to Christopher Beevers and shared equipment grants from the National Center for Research Resources (1S10RR023457) and the Department of Veteran Affairs to John McGreary. The authors thank Christina Song for her assistance in data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beck AT. Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. Harper & Row; New York: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Posner MI, Rothbart MK. Developing mechanisms of self-regulation. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12:427–441. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koster EHW, Raedt RD, Goeleven E, Franck E, Crombez G. Mood-congruent attentional bias in dysphoria: Maintained attention to and impaired disengagement from negative information. Emotion. 2005;5:446–455. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.4.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and non-anxious individuals: A metaanalytic study. Psychol Bull. 2007;113:1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathews A, MacLeod C. Cognitive approaches to emotion and emotional disorders. Annu Rev Psychol. 1994;45:25–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.45.020194.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacLeod C, Rutherford E, Campbell L, et al. Selective attention and emotional vulnerability: Assessing the causal basis of their association through the experimental manipulation of attentional bias. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:107–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox E. Allocation of visual attention and anxiety. Cognition Emotion. 1993;7:207–215. doi: 10.1080/02699939308409185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beevers CG, Carver CS. Attentional bias and mood persistence as prospective predictors of dysphoria. Cognitive Ther Res. 2003;27:619–637. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox E, Cahill S, Zougkou K. Preconscious processing biases predict emotional reactivity to stress. Biol Psychiat. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.018. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacLeod C, Koster E, Fox E. Whither cognitive bias modification research? Commentary on the special section articles. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:89–99. doi: 10.1037/a0014878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canli T, Lesch KP. Long story short: The serotonin transporter in emotion regulation and social cognition. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1103–1109. doi: 10.1038/nn1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinz A, Jones DW, Mazzanti C, et al. A relationship between serotonin transporter genotype and in vivo protein expression and alcohol neurotoxicity. Biol Psychiat. 2000;47:643–649. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, et al. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science. 1996;274:1527–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drevets WC. Neuroimaging studies of mood disorders. Biol Psychiat. 2000;48:813–829. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beevers CG, Pacheco J, Clasen P, McGeary JE, Schnyer D. Lateral prefrontal cortex morphology and biased attention for emotional stimuli: Moderation by the serotonin transporter promoter region gene. Genes Brain Behav. 2010;9:224–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinz A, Braus DF, Smolka MN, et al. Amygdala-prefrontal coupling depends on a genetic variation of the serotonin transporter. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:20–21. doi: 10.1038/nn1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, et al. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala. Science. 2002;297:400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1071829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hariri AR, Drabant EM, Munoz KE, et al. A susceptibility gene for affective disorders and the response of the human amygdala. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2005;62:146–152. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pezawas L, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Drabant EM, et al. 5-HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulate-amygdala interactions: A genetic susceptibility mechanism for depression. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:828–834. doi: 10.1038/nn1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canli T, Omura K, Haas BW, et al. Beyond affect: A role for genetic variation of the serotonin transporter in neural activation during a cognitive attention task. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12224–12229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503880102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beevers CG, Gibb BE, McGreary JE, Miller IW. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and biased attention for emotional word stimuli among psychiatric inpatients. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116:208–212. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beevers CG, Wells TT, Ellis AJ, McGreary JE. Association of the serotonin transporter gene promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism with biased attention for emotional stimuli. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:670–681. doi: 10.1037/a0016198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox E, Ridgewell A, Ashwin C. Looking on the bright side: Biased attention and the human serotonin transporter gene. P R Soc B. 2009;276:1747–1751. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pérez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, McDermott JM, et al. Variations in the serotonin-transporter gene are associated with attention bias patterns to positive and negative emotion faces. Biol Psychol. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.08.009. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ioannidis JPA, Ntzani EE, Trikalinos TA, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG. Replication validity of genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2001;29:306–309. doi: 10.1038/ng749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu X, Oroszi G, Chun J, Smith TL, Goldman D, Schuckit MA. An expanded evaluation of the relationship of four alleles to the level of response to alcohol and alcoholism risk. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:8–16. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000150008.68473.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Rial WY, Rickels K. Short form of depression inventory: Cross validation. Psychol Rep. 1974;34:1184–1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psych. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.John OP, Srivastava S. The big-five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin L, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 2nd ed. Guilford; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seligman MEP, Abramson LY, Semmel A, von Baeyer C. Depressive attributional style. J Abnorm Psychol. 1979;88:242–247. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.88.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.John CH. Emotionality ratings and free-association norms of 240 emotional and non-emotional words. Cognition Emotion. 1988;2:49–70. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathews A, MacLeod C. Selective processing of threat cues in anxiety states. Behav Res Ther. 1985;23:563–569. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(85)90104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lench N, Stanier P, Williamson R. Simple non-invasive method to obtain DNA for gene analysis. Lancet. 1988;1:1356–1358. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meulenbelt I, Droog S, Trommelen GJ, et al. High-yield noninvasive human genomic DNA isolation method for genetic studies in geographically dispersed families and populations. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:1252–1254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spitz E, Moutier R, Reed T, et al. Comparative diagnoses of twin zygosity by SSLP variant analysis, questionnaire, and dermatoglyphic analysis. Behav Genet. 1996;26:55–64. doi: 10.1007/BF02361159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freeman B, Powell J, Ball D, et al. DNA by mail: An inexpensive and noninvasive method for collecting DNA samples from widely dispersed populations. Behav Genet. 1997;27:251–257. doi: 10.1023/a:1025614231190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wigg KG, Takhar A, Ickowicz A, et al. Gene for the serotonin transporter and ADHD: No association with two functional polymorphisms. Am J Med Genet B. 2006;141:566–570. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Contreres S, Fernandez S, Malcarne VL, Ingram RE, Vaccarino VR. Reliability and validity of the Beck depression and anxiety inventories in Caucasian Americans and Latinos. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2004;26:446–462. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gotlib IH, Krasnoperova E, Yue DN, Joormann J. Attentional biases for negative interpersonal stimuli in clinical depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113:127–135. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Risch N, Herrell R, Lehner T, et al. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301:2463–2471. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenthal R. Replication in behavioral research. J Soc Behav Pers. 1990;5:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munafo M, Brown S, Hariri A. Serotonin Transporter (5-HHTLPR) Genotype and Amygdala Activation: A Meta-Analysis. Biol Psychiat. 2009;63:852–857. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amir N, Beard C, Burns M, Bomyea J. Attention modification program in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:28–33. doi: 10.1037/a0012589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt NB, Richey JA, Buckner JD, Timpano KR. Attention training for generalized social anxiety disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:5–14. doi: 10.1037/a0013643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wells TT, Beevers CG. Biased attention and dysphoria: Manipulating selective attention reduces subsequent depressive symptoms. Cognition Emotion. in press. [Google Scholar]