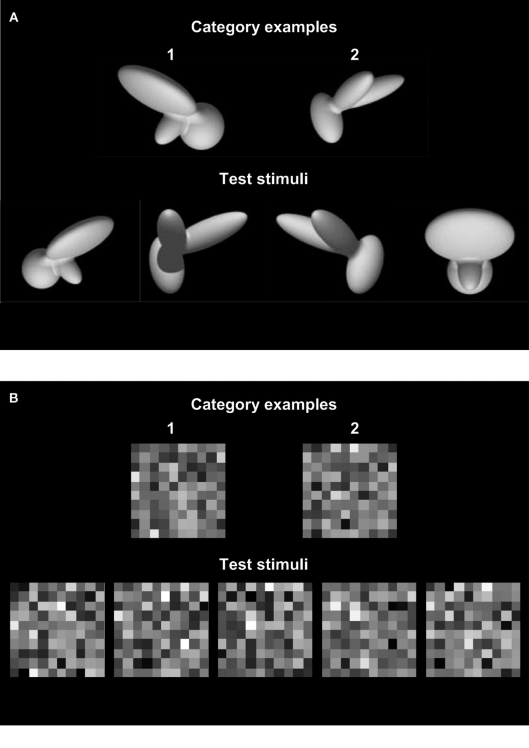

Figure 1.

Examples of invariant and non-invariant object recognition. (A) Single exemplars of two categories (‘1’ and ‘2’; stimuli taken from Zoccolan et al., 2009) are shown in the upper row. When asked to classify unknown instances of these new visual objects (bottom row), human observers solve this problem effortlessly and “see” that the right answer is ‘1, 2, 2, 1’. This is remarkable, given that an ideal observer having access to all available image information, but lacking knowledge of image formation and geometrical transformations, cannot perform this task correctly. Such an ideal observer bases classification on a pixel-by-pixel comparison (Green and Swets, 1966) and judges the test stimuli depicted in the bottom row to belong to category ‘2, 2, 1, 1’, respectively. (B) The tolerance for irrelevant variations in object appearance that is achieved by the human visual system is limited to “natural” irrelevant dimensions such as position, light and context. Although the task portrayed here is much simpler from a computational perspective and trivially easy for the ideal observer, most readers will find it very hard to ignore the irrelevant variations, i.e., weak random perturbations of the exact luminance levels of the category exemplars, and see that the patterns in the lower row belong to category ‘1, 1, 2, 1, 2’, respectively.