Abstract

Objective

This study investigated a multi-component cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) for hoarding based on a model proposed by Frost and colleagues and manualized in Steketee and Frost (2007).

Method

Participants with clinically significant hoarding were recruited from the community and a university-based anxiety clinic. Of 46 patients randomly assigned to CBT or WL, 40 completed the 12-week assessment and 36 completed 26 sessions. Treatment included education and case formulation, motivational interviewing, skills training for organizing and problem solving, direct exposure to non-acquiring and discarding, and cognitive therapy. Measures included the Saving Inventory-Revised (self-report), Hoarding Rating Scale-Interview, and measures of clinical global improvement. Between group repeated measures analyses using general linear modeling (GLM) examined the effect of CBT versus WL on hoarding symptoms and moodstate after 12 weeks. Within group analyses examined pre-post effects for all CBT participants combined after 26 sessions.

Results

After 12 weeks, CBT participants benefitted significantly more than WL patients on hoarding severity and mood with moderate effect sizes. After 26 sessions of CBT, participants showed significant reductions in hoarding symptoms with large effect sizes for most measures. At session 26, 68% of patients were considered improved on therapist clinical global improvement ratings, and 76% of patients rated themselves as improved; 41% of completers were clinically significantly improved.

Conclusions

Multi-component CBT was effective in treating hoarding. However, treatment refusal and compliance remain a concern and further research with independent assessors is needed to establish treatment benefits and durability of gains.

Introduction

Features of hoarding include difficulty parting with personal possessions, even those of apparently useless or limited value, resulting in the accumulation of large amounts of clutter in the living areas of the home and often other personal and/or work environments (1). Excessive acquiring through buying or collecting free items is also evident in most cases (2). These symptoms impair functioning and/or pose significant health and safety risks, as well as distress to those who hoard and/or those living with or near them (3–6).

Although hoarding has traditionally been considered a subtype of OCD, increasing evidence points to substantial differences in clinical and biological features (7–10). Hoarding is also included in DSM-IV-TR as a symptom of obsessive compulsive personality disorder, but does not appear strongly associated with other features of this condition (see review by Pertusa and colleagues, 11). Epidemiological findings indicate that clinically significant hoarding occurs in 2–5% of the population, making it a strikingly common problem (12–14).

Retrospective treatment studies have recruited OCD patients with hoarding symptoms rather than people with hoarding as a primary problem. Most large scale pharmacological studies have found that hoarding symptoms predict poor outcomes following SRI treatment (15), and another study reported non-significant trends for hoarding to predict worse outcome (e.g., 16). A prospective study by Saxena et al. (17) reported no difference in response to paroxetine among hoarding and non-hoarding OCD patients; however, both groups showed only modest improvement (approximately 25%) on standard measures of OCD symptoms.

Findings from retrospective studies of behavioral treatments for OCD patients with hoarding symptoms have followed the trend of hoarding predicting worse outcomes. This was evident for a computer-based behavioral therapy (18) and for therapist administered exposure and response prevention (ERP), a CBT method developed for OCD that utilizes prolonged exposure to increasingly feared obsessive situations and gradual blocking of rituals associated with these obsessions to achieve habituation of fear and reduction or elimination of rituals. Abramowitz and colleagues (19) reported that only 31% of hoarders exhibited a clinically significant response compared to 46–76% of patients with non-hoarding OCD, a relatively poor response for hoarding to this typically effective ERP method. Unfortunately, these studies suffer from sampling and measurement problems, with most recruiting hoarding patients from OCD clinics and utilizing the 2-item Symptom Checklist of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale to identify hoarders. Retrospective studies that have combined serotonergic medication with behavior therapy for OCD also reported disappointing outcomes for hoarding compared to non-hoarding OCD patients (20–22). Descriptive case reports of hoarding patients receiving behavior therapy have reported generally negative treatment outcomes accompanied by poor insight, treatment refusal, and lack of cooperation (23–28).

Over the past decade, a cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding has emerged (1, 7, 29) that posits that the excessive acquisition, difficulty discarding, and clutter that comprise hoarding stem from information processing deficits, problematic beliefs and behaviors, and emotional distress and avoidance. Research findings support many aspects of the model, including problems with focusing and sustaining attention (30, 31), categorizing possessions (32), and decision making (33), as well as problematic beliefs about possessions (34–36). The model proposes that strong negative emotional reactions to possessions (e.g., anxiety, grief, guilt) lead to avoidance of discarding and organizing, while strong positive emotions (pleasure, joy) reinforce acquiring and saving possessions (Steketee & Frost, (7)).

In a recent open trial, Tolin, Frost and Steketee (37) tested a multi-component cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) intervention for hoarding based on this model. Treatment included office and home visits with motivational interviewing to address low insight and limited motivation, decision-making training to improve cognitive processing, exposure to reduce negative emotions associated with discarding and resisting acquiring, and cognitive restructuring to alter beliefs. This treatment resulted in reductions of the major manifestations of hoarding (clutter, difficulty discarding, acquiring) in 14 adults, of whom 10 completed 26 sessions of treatment over 7 to12 months. Significant decreases from pre- to post-treatment were evident on standardized measures of hoarding symptoms, and at post-treatment, half of the sample (n = 5) were rated much or very much improved on clinical global improvement ratings.

Following upon this pilot work and minor modifications to the treatment protocol, the present study tested these CBT methods in a waitlist controlled trial conducted at two sites. CBT was hypothesized to lead to greater improvement in hoarding symptoms than a wait period of 12 weeks for patients seeking treatment for hoarding. In addition, 26 sessions of this treatment was expected to produce significant and substantial benefits on hoarding symptoms.

Methods

Design and Participants

Participants were recruited from anxiety clinics at Boston University and The Institute of Living, from community service providers and from local and national media presentations. No formal advertising was employed and participants were not recruited through OCD specialty clinics. Inclusion criteria were adults ≥18 whose most severe problem was hoarding; symptoms of clutter and difficulty discarding were at least moderately severe (≥ 4 on 0–8 ratings of the Hoarding Rating Scale (see below). Patients were excluded if they reported current psychotic symptoms, bipolar disorder, serious cognitive impairment that would interfere with accurate reporting, substance use disorder within the past 6 months, were receiving concurrent psychotherapy, or had received psychiatric medications within the past month. We also excluded participants who hoarded animals as treatment was not designed to address this problem. The need for monthly home visits required that we include participants who lived within 45 minutes of the clinic.

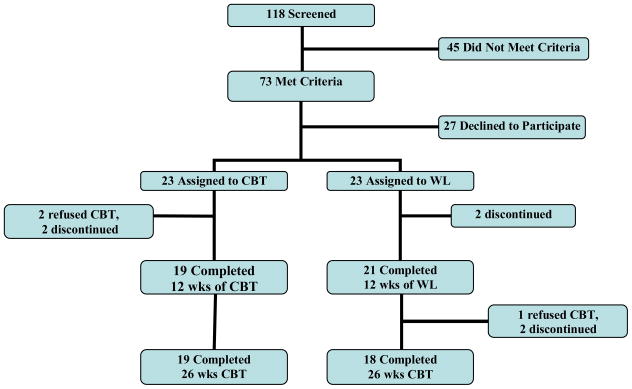

Figure 1 illustrates participant flow through the study. After a detailed description of the study to 46 patients who met criteria and provided written informed consent, 23 were randomly assigned to immediate CBT (26 sessions) and 23 to a 12-week waitlist (WL) before receiving 26 sessions of CBT. Two participants assigned to CBT refused treatment and another two discontinued before session 10, leaving 19 completers in the immediate CBT group. Of those assigned to WL, two discontinued (animal hoarding was discovered at one home visit and one did not complete assessments), leaving 21 waitlist completers who were invited to continue into CBT. One refused CBT and two discontinued before week 10. Taken together, of 44 patients offered CBT immediately (23) or following WL (21), 3 declined and 4 discontinued (<10 sessions), representing 16% of the sample; the reasons given were scheduling conflicts, long travel times to therapy sessions, and feeling too overwhelmed to engage in therapy.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for hoarding treatment study enrollment

The sample included 75% women and was 87% Caucasian (minority representation included 1 Latino, 5 Black, 1 Asian); mean age was 54. Thirty-six percent had never married, 40% were married/living with partner and 24% were divorced/separated or widowed. Most (66%) worked full- or part-time or were students and 32% were unemployed. In this generally well educated sample, 40% reported having graduate education, 19% completed college, 26% had some college education and 11% completed high school.

Measures

The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS-IV; 38) was used to determine diagnosis for anxiety, mood, somatoform, and substance use disorders and to screen for the presence of other conditions (e.g., psychosis). The ADIS-IV-L has produced good to excellent reliability estimates for the majority of anxiety and mood disorders, including κ = .85 for principal OCD diagnoses (39). Cross-site and rater reliability was accomplished via extensive ongoing training by ADIS developers and by research team consensus regarding principal and secondary diagnoses for all participants.

The Saving Inventory-Revised (SI-R; 40) is a 23-item self-report questionnaire scored from 0 (no problem) to 4 (very severe, extreme); 3 factor analytically defined subscales are difficulty discarding, excessive clutter and compulsive acquisition. The SI-R showed good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, known groups validity and concurrent and divergent validity in clinical and non-clinical samples. Cronbach’s alpha for baseline SI-R in this sample was .88. Mean scores of 50 and above are typical of hoarding samples with clinically significant symptoms, whereas means for non-hoarding clinical samples and community samples score are in the 22–24 range (40).

Hoarding Rating Scale-Interview (HRS-I; 41) is a brief 5-item semi-structured interview completed by the assessor to rate clutter, difficulty discarding, acquisition, distress, and impairment on scales from 0 to 8. All 5 items were summed to yield a total score ranging from 0 to 40. The HRS-I has shown high internal consistency and reliability across time, context, and raters, as well as know groups and construct validity. Internal consistency for the sample was .79. A total cutoff score of 14 and above distinguished hoarding from OCD patients; mean scores of 20 and above are typical for clinical hoarding samples, and mean scores in the 3 to 4 range were typical of non-hoarding clinical and non-clinical samples (41).

The NIMH Clinician Global Impression - Improvement ratings (CGI; 42) were made by therapists at the end of the wait list period, session 12, and session 26 and ranged from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse). Patient CGI-I ratings were collected at CBT sessions 12 and 26 (self-ratings were not collected at post-waitlist).

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; 43) is a 21-item self-report inventory of depression shows good internal consistency and reasonable construct validity (Beck et al., 1996;). Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was .94.

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; 44) is a 21-item self-reported rating of anxiety with high internal consistency and satisfactory test-retest reliability. Internal consistency was .95 in this sample.

Procedure

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Boston University, Smith College, and Hartford Hospital. After initial telephone screening, potential participants met with a trained assessor who provided detailed information about the study, obtained informed consent and reviewed inclusion and exclusion criteria and severity of hoarding and other psychiatric conditions. Consenting participants with hoarding as their primary problem who met other criteria were randomly assigned to begin CBT immediately or after a 12-week wait period. Assessments were completed before treatment, after the wait period, after session 12, and after 26 sessions of CBT by patients and by clinicians who provided treatment and were not blind to the waitlist versus CBT condition.

Treatment

Therapists were advanced psychology graduate students and masters-level social workers who received extensive training in CBT for hoarding (29), watched motivational interviewing training videotapes (45), received weekly supervision from RF or GS who listened to audio recordings sessions and provided ongoing feedback. Formal fidelity ratings were not computed, but two pairs of graduate psychology students who assisted in developing adherence ratings reported good adherence for 6 patients treated by 3 different therapists. Treatment included 26 individual sessions scheduled approximately weekly in office (1 hour each) with every fourth session (2 hours) conducted in the home or at a local acquiring location. The average therapy duration was 44.8 weeks (range 28 to 77) due mainly to patient scheduling and motivational problems.

Treatment began with assessment and case formulation, developing an idiographic CBT model, and treatment planning. Motivational interviewing strategies were applied whenever therapists detected ambivalence (e.g., homework compliance, attendance problems). Therapists applied interventions skills training for organizing, decision-making, and problem solving; exposure to non-acquiring and discarding; and cognitive therapy for problematic hoarding-relevant beliefs. Techniques were applied flexibly based on the initial treatment plan and progress in various areas. Homework tasks decided at each session required patients to practice therapy methods several times per week. The last two sessions on relapse prevention addressed future progress and managing stressors without reverting to hoarding behaviors. In addition, 8 participants (4 at each site) with very severe clutter or physical limitations received 1 or 2 “marathon” sessions of 3–6 hours each in which the therapist and up to 4 other research team members traveled to the patient’s home to help with sorting, organizing, and discarding. All such intensive sessions occurred late in therapy after patients had learned skills and could provide direction to team members in what to discard. All decisions were made according to the patients’ rules.

This hoarding-focused CBT intervention differs from standard ERP for OCD by including specialized aspects of the hoarding problem in the patient case formulation (e.g., familial and biological vulnerability factors, cognitive processing problems, positive and negative emotions that reinforce saving and acquiring behaviors), as well as non-standard treatment components such as motivational interviewing and cognitive skills training in decision-making and problem solving. Other therapy elements – gradual exposure to discarding and non-acquiring situations (exposure), encouraging voluntary restriction of acquiring (response prevention), and Beckian cognitive therapy methods – are similar to those used in ERP and more recent cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for OCD.

Data Analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS v. 15 with SPSS Missing Value Analysis v. 7.5 (SPSS, 1997). Whenever possible, missing values were first replaced with actual data collected from an assessment close in time to the missing value. Accordingly, scores from the first home visit replaced missing baseline data for 3 participants (4 measures), session 16 data were substituted for missing session 12 data for 3 participants (5 measures), and session 8 data substituted for session 12 for 1 participant (1 measure). Remaining missing values were imputed using the expectation-maximization (EM) method which uses a conditional expectation of the missing data given the observed values and current estimates of the parameters, then computes maximum likelihood estimates of the parameters. The extent and effect of missing data are noted below where appropriate. In reporting treatment outcomes, we have included effect sizes calculated via partial eta squared (η2p) as well as the conversion to Cohen’s d as per Cohen (45).

Chi square and t-test (two-tailed) analyses first examined comparability of groups on baseline demographic and moodstate measures for WL and CBT participants and for CBT completers versus discontinuers. Repeated measures general linear modeling (GLM) analyses tested the hypothesis that 12 sessions of CBT would outperform waitlist using a 2 (site: Boston, Hartford) X 2 (group: WL, CBT) X 2 (time: baseline, 12 weeks) repeated measures mixed-factor GLM. Similar 2 (site) X 3 (time: pre, mid, post) repeated measures mixed GLM analyses tested the hypothesis that CBT participants would show significant improvement in hoarding symptoms from pre-treatment to mid (12 sessions) and post-treatment (26 sessions) for the 41 patients who began CBT. Outcome analyses were performed on both the intention-to-treat and completer samples, but because findings were very similar, only the former are reported here.

Results

Baseline Comparisons

Baseline comparisons of CBT versus WL participants (see Table 1) indicated no significant differences for gender, age, ethnicity/race, marital status, employment, anxiety (BAI), or depression (BDI, all ps >.05). Comparisons of treatment completers (n=36) to non-completers (n=11) at baseline on demographic variables and hoarding severity also indicated no significant differences (all ps>.05) in age, gender, race, marital status or employment, or mood state (BDI, BAI).

Table 1.

Demographic information and baseline symptom severity (frequency/mean, p value) for hoarding participants (intention-to-treat) assigned to waitlist (WL) versus cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) conditions.

| Variable | WL participants | CBT participants | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=23 | N=23 | ||

| Age | 53.3 (8.0) | 54.5 (8.2) | .60 |

| % female | 69.6 | 82.6 | .30 |

| % Caucasian | 91.3 | 82.6 | .38 |

| % married or cohabiting | 69.6 | 47.8 | .13 |

| % employed+ | 56.5 | 73.9 | .20 |

| % with BA or more | 54.5 | 65.2 | .47 |

| % with MDD | 47.8 | 39.1 | .55 |

| % with GAD | 34.8 | 34.8 | 1.0 |

| % with social phobia | 21.7 | 26.1 | .73 |

| SI-R total | 62.4 (10.6) | 63.5 (15.6) | .78 |

| HRS | 29.5 (5.5) | 29.9 (4.5) | .79 |

| BDI | 19.7 (11.6) | 13.5 (11.4) | .08 |

| BAI | 11.0 (10.8) | 11.3 (12.1) | .93 |

+ Employed full-time or part-time or student

BA = Bachelors of Arts degree, BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory, BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, GAD = generalized anxiety disorder, HRS = Hoarding Rating Scale, MDD = major depressive disorder, SI-R = Saving Inventory-Revised

CBT versus WL at Week 12

Intent-to-treat analyses included 46 patients (23 WL and 23 CBT)1. Mean scores for outcome variables are given in Table 2. SI-R subscale scores (Clutter, Difficulty Discarding, Acquisition)2 were examined first. As expected, a significant main effect of time (F1,44=15.603, p=.001, η2p=0.271 [Cohen’s d = 1.219]) was modified by a significant group X time interaction (F1,44=10.749, p=.002, η2p=0.204 [Cohen’s d = 1.012]). Because none of the interaction effects involving time and subscale were significant (all ps>.05), follow-up tests were conducted using the SI-R total score. Again, a significant main effect of time emerged (F1,44=15.007, p=.001, η2p=0.263 [Cohen’s d = 1.195]) as well as the predicted group x time interaction (F1,44=10.719, p=.002, η2p=0.203 [Cohen’s d = 1.009]). No site by time interactions were significant (ps>.05). As Table 2 indicates, the WL group showed minimal reduction in SI-R scores, t(22)=0.50, p>.05, whereas the CBT group showed a nearly 10-point (15%) average reduction in total SI-R scores, t(22)=4.54, p<.001.

Table 2.

Means (standard deviations) and effect sizes from general linear modeling (GLM) analyses comparing treated versus waitlisted hoarding participants after 12 weeks.

| Measure | N | Baseline | SD | Wk 12 | SD | Partial eta squared | Cohen’s d conversion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI-R Total | CBT | 23 | 63.42 | 14.95 | 53.73 | 18.47 | .223 | 1.071 |

| WL | 23 | 62.39 | 10.60 | 61.21 | 13.05 | |||

| Clutter | CBT | 23 | 27.37 | 7.09 | 24.16 | 9.42 | .135 | .790 |

| WL | 23 | 27.17 | 4.07 | 27.17 | 4.89 | |||

| Discarding | CBT | 23 | 20.03 | 4.40 | 16.93 | 5.57 | .090 | .629 |

| WL | 23 | 20.22 | 3.38 | 19.67 | 4.03 | |||

| Acquiring | CBT | 23 | 16.10 | 6.45 | 12.67 | 6.96 | .120 | .739 |

| WL | 23 | 15.55 | 6.43 | 14.37 | 6.73 | |||

| HRS | CBT | 23 | 29.88 | 4.47 | 21.68 | 6.97 | .111 | .707 |

| WL | 23 | 29.48 | 5.48 | 25.83 | 4.40 | |||

| BDI-II | CBT | 14 | 11.25 | 10.53 | 11.59 | 11.69 | .017 | .263 |

| WL | 18 | 19.18 | 10.51 | 17.84 | 10.71 | |||

| BAI | CBT | 14 | 10.49 | 11.89 | 9.66 | 7.51 | .001 | .063 |

| WL | 20 | 9.38 | 6.72 | 9.00 | 7.92 | |||

| CGI therapist | CBT | 23 | - | - | 2.72 | .74 | .403 | 1.643 |

| WL | 23 | - | - | 3.84 | .62 |

CGI = Clinical Global Improvement; HRS = Hoarding Rating Scale; SI-R = Saving Inventory Revised

Results from analyses of HRS-I scores showed a significant main effect of time (F1,42=60.037, p<0.001, η2p=0.588 [Cohen’s d = 2.389]), modified by a significant group X time interaction (F1,42=8.446, p=0.006, η2p=0.167 [Cohen’s d = .896]). While both the CBT and WL groups improved (ts[22]= 6.0 and 4.5, respectively, ps<.05), CBT led to more improvement than did WL (see Table 2). However, site interactions were significant for this variable, including time X site (F1,42=5.829, p=0.020, η2p=0.122 [Cohen’s d = .764]) and time X site X group (F1,42=5.612, p=.023, η2p=0.118 [Cohen’s d = .732]). Post hoc analyses indicated that Boston patients treated with CBT showed substantial reduction in hoarding symptoms, whereas Hartford CBT patients and WL participants from both sites improved only modestly.

Analyses of session 12 outcomes for depressed (BDI-II) and anxious (BAI) mood indicated no significant effect of time or group X time interaction (all ps > .479). As evident on Table 2, the samples for these analyses were small (Ns = 14 for CBT and 18-20 for WL), standard deviations were large, and severity levels were low to moderate. Univariate ANOVAs used to examine therapist CGI-I ratings at session 12 showed a main effect of group (F1,42=28.341, p=.001, η2p=.403) in which CBT participants were rated as showing more average improvement than WL participants (see Table 2). No site effect or site x group interaction emerged (ps>.05). When therapist CGI-I scores at 12 weeks were recoded into “very much” or “much improved” (scores of 1 or 2) versus “not improved” (score of 3–7)3, none (0%) of the WL patients and 10 (43.5%) of the CBT patients were rated improved, a significant difference according to Fisher’s Exact Test (p=.001).

Pre-Mid-Post Changes in the Combined CBT Sample

Intent-to-treat analyses examined all participants assigned to immediate and delayed CBT (N=41). Mean scores for pretest, session 12, and session 26 and effect sizes (partial eta squared (η2p) from GLM analyses are reported in Table 3. Missing data were addressed as described earlier.4 SI-R scores were analyzed using a 3 (time: pre-treatment, session 12, session 26) X 3 (scale: Clutter, Difficulty Discarding, Acquisition) X 2 (site: Boston, Hartford) repeated-measures GLM with time and scale as repeated measures. Results showed a significant main effects of time (F2,38=33.265, p<.001, η2p=0.460) and of subscale (F2,78=86.506, p<.001, η2p = 0.689). The time by site interactions were not significant (time x site, F2,38=1.682, p=.20; time x site x subscale F4,36=1.940, p=.125), indicating that outcomes were comparable across the two sites. The time by subscale interaction was significant, F4,36= 3.895, p<0.01; we therefore followed up with analyses for SI-R subscales as well as the total score. Significant time effects emerged for all scales: total score F2,80=32.648, p<.001, clutter F2,80=27.666, p<.001, difficulty discarding F2,80=23.668, p<.001, acquiring F2,80=14.894, p<.001; all η2ps≥.271 (see Table 3). Pairwise comparisons indicated significant declines in SI-R total scores from pre-treatment to session 12, and again from session 12 to session 26 (ps<.05).

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations (SD) at pretreatment, 12 and 26 sessions and effect sizes (partial eta squared) for time for 41 hoarding participants who received cognitive behavior therapy.

| Measure | Pretest | SD | Session 12 | SD | Session 26 | SD | η2p | Cohen’s d conversion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI-R Total | 61.69 | 15.49 | 54.17 | 15.98 | 44.77 | 18.59 | .449 | 1.805 |

| Clutter | 26.94 | 6.80 | 24.63 | 7.91 | 19.61 | 8.47 | .409 | 1.664 |

| Discarding | 19.78 | 4.77 | 16.63 | 5.34 | 14.43 | 6.20 | .372 | 1.539 |

| Acquiring | 14.98 | 6.74 | 12.91 | 6.70 | 10.73 | 6.30 | .271 | 1.219 |

| HRS | 28.18 | 4.95 | 22.23 | 6.13 | 17.18 | 8.09 | .568 | 2.293 |

| BDI-II | 12.57 | 9.56 | 14.47 | 11.50 | 11.43 | 8.63 | .065 | .527 |

| BAI | 9.32 | 10.05 | 9.28 | 7.86 | 7.98 | 9.71 | .030 | .352 |

| CGI therapist | - | - | 2.64 | .69 | 2.06 | .73 | .381 | 1.569 |

| CGI patient | - | - | 2.44 | .66 | 2.06 | .78 | .286 | 1.266 |

N=41 includes 21 patients who received immediate CBT and 20 who began CBT after waitlist. CGI = Clinical Global Improvement; HRS = Hoarding Rating Scale; SI-R = Saving Inventory Revised

HRS-I scores were analyzed using a repeated-measures GLM examining site X time (pre-treatment, session 12, session 26). Results showed a significant main effect of time (F2,78=51.342, p<.001, η2p=0.568 [Cohen’s d = 2.293]) and no time X site interaction (p>.08), indicating comparable effects across sites. Follow-up pairwise comparisons showed that HRS-I scores decreased significantly from pre-treatment to session 12, and again from session 12 to session 26 (ps<.05). As for session 12, analyses of outcomes on the BDI-II and BAI showed no significant changes over time (all ps > .20); again sample sizes were smaller (ns=25–26) than for other analyses and mean scores showed moderate severity and high variability.

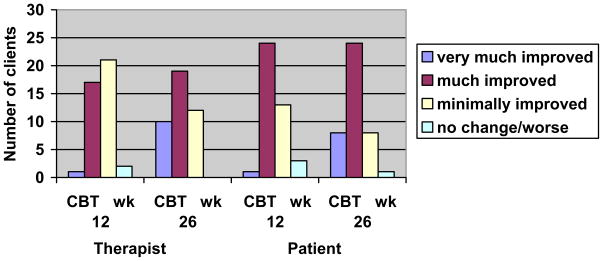

Table 3 contains mean scores and effect sizes for therapist and self-reported CGI-I ratings for 41 patients who entered CBT. GLM analyses examined time (session 12, session 26) as a repeated measure and site effects. Therapist ratings showed a main effect of time (F1,39=24.003, p<.001) and no site interaction (p>.20). Self-rated CGI also showed a main effect of time (F1,39=15.659, p<.001), again with no site effect (p > .47). Effect sizes (partial eta squared) were large for time effects on both measures (see Table 3). Figure 2 provides the number of patients who received specific scores on these measures. When participants were classified as “improved” (score of 1 “very much” or 2 “much improved”) versus “not improved” (score of 3–7) at 12 sessions, 18 (43.9%) received therapist ratings of improved, and 25 (61.0%) rated themselves as improved. After session 26, 29 (70.7%) received therapist ratings of improved, and 33 (80.5%) rated themselves as improved. Fifteen of the 37 clients (41%) who completed treatment were classified as clinically significantly improved on both the SIR and HRS using Jacobson and Truax (46) criteria.

Figure 2.

Therapist and patient ratings of Clinical Global Improvement (CGI) after 12 and 26 sessions of cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT).

Discussion

Findings from this waitlist controlled trial indicated that after 12 sessions, a multi-component CBT intervention based on a model of hoarding psychopathology led to significantly more improvement in hoarding symptoms than did a comparable waiting period. Large between-group differences in effect sizes (partial eta squared) were observed, particularly for self-reported overall hoarding (SI-R total) and therapist rated clinical global improvement. Patients reported improvement in specific symptoms of clutter, difficulty discarding and acquiring, consistent with previous treatment studies (37, 48). Given the consistency with which reports in the literature describe hoarding patients as difficult to treat, the extent of improvement after a relatively limited amount of treatment (12 sessions) seems promising.

The baseline to mid-treatment and post-treatment comparisons for the 41 patients who began CBT indicated significant improvement from baseline on all measures of hoarding symptoms. Effect sizes were large and means suggest substantial improvement on average across all patients. As expected, gains were evident for each of the three hoarding symptoms, with acquiring showing somewhat more modest average improvement. Measures of depressed and anxious mood showed little reduction during treatment. Although treatment included cognitive therapy methods likely to improve depression and exposures designed to habituate anxiety associated with hoarding, the greater than usual missing data and moderate baseline scores, as well as high variability (some standard deviations were greater than the means) likely played a role in these findings.

According to therapist ratings, clinical global improvement occurred in about 70% of patients who were rated improved compared to 50% in the Tolin et al. (37) pilot trial. Despite these relatively high improvement rates, only 24% (10/41) were rated in the highest category of “very much improved,” indicating that the large majority continued to have clinically significant difficulty. In addition, only 41% met criteria for clinically significant change. Although this is considerably higher than previous findings for hoarding (19), it is still below what has been found for the treatment of OCD (19). In our experience, even patients who benefit greatly from 26 sessions of this specialized CBT require further aid to fully clear their homes and maintain clutter-free living spaces.

It is noteworthy that of 73 patients with hoarding problems who qualified initially for the study, 27 (37%) declined to participate and another 5 (total of 44%) discontinued before entering CBT. Reasons for this high refusal rate are unclear and require further study. Although some participants gave reasons such as distance to the clinic, we suspect many treatment seekers with hoarding were still ambivalent about resolving their problem, consistent with the limited insight and low motivation reported by many other investigators (18, 49). In contrast, the dropout rate for those who began CBT (4 of 41, 10%) for this study was quite modest and substantially better than the 29% discontinuation rate in our small pilot trial (37). This came at some cost, however, as therapists permitted patients to continue in treatment despite repeated late arrivals and missed appointments that indicated ambivalence. In fact, the 26-session therapy required an average of 49 weeks to complete despite the intended weekly sessions. Therapists also reported that hoarding patients often had difficulty completing homework assignments and required frequent motivational enhancement strategies during sessions, especially early in treatment.

This initial test of CBT for hoarding has several limitations. The sample included mainly women whereas at least two epidemiological studies indicate that hoarding may be more common among men (12, 14). Further, it is not clear that findings for this largely white highly educated adult sample will generalize to other more diverse populations. Other concerns include the lack of an independent assessor blind to treatment condition, the lack of reliability data for the ADIS and HRS clinician assessments, and the amount of missing data at week 12, especially for CBT participants, which may have affected the findings despite findings of randomness of the missing data. Further, we did find unexpected site differences for the HRS interview measure which might have been due to the higher dropout rate for the Hartford versus Boston site (3 vs 0) in the WL condition. However, this was the only site difference obtained. In addition, because treatment fidelity ratings were completed only for a small portion of patients (n=6) whose sessions were also used to help develop and test adherence rating forms, we cannot state with certainty that all therapists adhered to the manual. However, all were supervised closely by the senior authors (GS, RF) who listened to clinic session audiotapes and provided feedback on all patients’ treatment. In addition, RF listened to taped sessions from both Boston and Hartford therapists to verify that treatment was being delivered comparably across sites.

Overall, the CBT methods employed in this study appear to benefit patients with hoarding symptoms and to improve upon standard exposure and response prevention (ERP) applied in previous studies. However, in the absence of a control group that received ERP, we cannot draw this conclusion. Thus, it remains important to determine whether the multi-component CBT methods employed here are superior to ERP for patients with primary hoarding and whether these effects are lasting. Additionally, it is not clear what the various components of this CBT treatment contribute to the overall benefits. Finally, potential benefits from adding medications to these CBT methods remain to be studied.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant R21 MH68539 awarded to Dr. Steketee.

This study was funded by NIMH grant R21 MH068539 to the first author.

The authors thank study coordinators Robert Brady, Patrick Worhunsky and Cristina Sorrentino; research assistants/therapists Ancy Cherian and Amanda Gibson from the Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders at Boston University; research assistants Stefanie Renaud and Laura Fabricant from Smith College; and Johanna Crocetto and Robert Brady from The Institute of Living. Additional study therapists from Boston University included Shawnee Basden, Terry Lewis, and Dr. Christiana Bratiotis. Study therapists from The Institute of Living included Dr. Scott Hannan, Dr. Nicholas Maltby, Dr. Suzanne Meunier, David Klemanski, Krista Gray, Matthew Monteiro, and Danielle Koby.

Footnotes

Previous presentation: Portions of this study were presented at the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy, Philadelphia, PA, November 16–18, 2007.

Examination of missing data on the main outcome variables at 12 weeks showed that 7 (15.2%) participants were missing SI-R and HRS-I data, and 11 (23.9%) were missing CGI data. Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test was not significant [χ2 (5) = 2.607, p = .760], suggesting randomness in the missing data.

In these analyses, SI-R subscale scores were summed and divided by the number of items per scale to yield average subscale scores. However, Table 2 provides the summed score for each subscale to facilitate comparison with previous published findings.

When missing CGI-I values were imputed, scores less than or equal to 2.500 were considered improved, and scores of 2.501 or greater were considered not improved.

In addition to the specific data substitutions noted for earlier analyses, session 16 measures were substituted for missing data at post-treatment for one participant who stopped CBT after 19 sessions due to lack of motivation and failure to complete therapy activities. Further, 5 (12.2%) patients were missing SI-R data at 12 weeks and 4 (9.8%) at 26 weeks; 5 (12.2%) were missing HRS-I data at 12 weeks and 4 (9.8%) at 26 weeks; 7 (17.1%) were missing therapist-rated CGI ratings at 12 weeks and 4 (9.8%) at 26 weeks; 8 (19.5%) were missing self-rated CGI at 12 weeks and 5 (12.2%) at 26 weeks. Little’s MCAR test was not significant [χ2 (83) = 0.000, p = 1.000], suggesting randomness in the missing data.

Disclosures: Drs. Steketee, Frost, and Tolin receive royalties from Oxford University Press (OUP) for publication of a self-help version of the therapy methods (Tolin, Frost & Steketee, Buried in Treasures). Drs. Steketee and Frost also receive royalties from the therapist guide and client workbook describing the methods used in this study (Steketee & Frost, Compulsive Hoarding and Acquiring), and are under contract with Harcourt Press to publish Stuff: Hoarding and the Meaning of Things for a public audience. Dr. Tolin received funding from the following sources: Schering-Plough, Indevus Pharmaceuticals, and Eli Lilly.

References

- 1.Frost RO, Hartl TL. A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:341–50. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frost RO, Tolin DF, Steketee G, Fitch KE, Selbo-Bruns A. Excessive acquisition in hoarding. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:632–9. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steketee G, Frost RO, Kim HJ. Hoarding by elderly people. Health Soc Work. 2001;26:176–84. doi: 10.1093/hsw/26.3.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frost RO, Steketee G, Williams LF, Warren R. Mood, personality disorder symptoms and disability in obsessive compulsive hoarders: a comparison with clinical and nonclinical controls. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:1071–81. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G, Gray KD, Fitch KE. The economic and social burden of compulsive hoarding. Psychiat Res. 2008;160:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G, Fitch KE. Family burden of compulsive hoarding: results of an internet survey. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:334–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steketee G, Frost RO. Compulsive hoarding: Current status of the research. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:905–927. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tolin DF, Kiehl KA, Worhunsky P, Book GA, Maltby N. An exploratory study of the neural mechanisms of decision making in compulsive hoarding. Psychol Med. 2009;39:325–36. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mataix-Cols D, Wooderson S, Lawrence N, Brammer MJ, Speckens A, Phillips ML. Distinct neural correlates of washing, checking, and hoarding symptom dimensions in obsessive- compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:564–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saxena S, Brody AL, Maidment KM, Smith EC, Zohrabi N, Katz E, et al. Cerebral glucose metabolism in obsessive-compulsive hoarding. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1038–48. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pertusa A, Frost RO, Fullana MA, Samuels J, Steketee G, Tolin DF, et al. Refining the diagnostic boundaries of compulsive hoarding: A critical review. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.007. Submitted for publication 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iervolino AC, Perroud N, Fullana MA, Guipponi M, Cherkas L, Collier DA, et al. Prevalence and heritability of compulsive hoarding: A twin study. American Journal of Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121789. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller A, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Glaesmer H, de Zwaan M. The prevalence of compulsive hoarding and its association with compulsive buying in a German population-based sample. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:705–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ, Grados MA, Cullen B, Riddle MA, Liang KY, et al. Prevalence and correlates of hoarding behavior in a community-based sample. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:836–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mataix-Cols D, Rauch SL, Manzo PA, Jenike MA, Baer L. Use of factor-analyzed symptom dimensions to predict outcome with serotonin reuptake inhibitors and placebo in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1409–16. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erzegovesi S, Cavallini MC, Cavedini P, Diaferia G, Locatelli M, Bellodi L. Clinical predictors of drug response in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:488–92. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saxena S, Brody AL, Maidment KM, Baxter LR., Jr Paroxetine treatment of compulsive hoarding. J Psychiatr Res. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mataix-Cols D, Marks IM, Greist JH, Kobak KA, Baer L. Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions as predictors of compliance with and response to behaviour therapy: results from a controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2002;71:255–62. doi: 10.1159/000064812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abramowitz JS, Franklin ME, Schwartz SA, Furr JM. Symptom presentation and outcome of cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:1049–57. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Black DW, Monahan P, Gable J, Blum N, Clancy G, Baker P. Hoarding and treatment response in 38 nondepressed subjects with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:420–5. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saxena S, Maidment KM, Vapnik T, Golden G, Rishwain T, Rosen RM, et al. Obsessive-compulsive hoarding: symptom severity and response to multimodal treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:21–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winsberg ME, Cassic KS, Koran LM. Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a report of 20 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:591–7. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenberg D. Compulsive hoarding. Am J Psychother. 1987;41:409–16. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1987.41.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenberg D, Witztum E, Levy A. Hoarding as a psychiatric symptom. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1990;51:417–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christensen DD, Greist JH. The challenge of obsessive-compulsive disorder hoarding. Primary Psychiatry. 2001;8:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damecour CL, Charron M. Hoarding: a symptom, not a syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:267–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fitzgerald PB. The ‘bowerbird symptom’: A case of severe hoarding of possessions. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;31:597–600. doi: 10.3109/00048679709065083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shafran R, Tallis F. Obsessive-compulsive hoarding: A cognitive-behavioral approach. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1996;24:209–221. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steketee G, Frost RO. Compulsive hoarding and acquiring: Therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hartl TL, Duffany SR, Allen GJ, Steketee G, Frost RO. Relationships among compulsive hoarding, trauma, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:269–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grisham JR, Brown TA, Savage CR, Steketee G, Barlow DH. Neuropsychological impairment associated with compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1471–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wincze JP, Steketee G, Frost RO. Categorization in compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2006;45:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maltby N, Kiehl KA, Worhunsky P, Tolin DF. An fMRI examination of the cognitive behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Submitted for publication 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hartl TL, Frost RO, Allen GJ, Deckersbach T, Steketee G, Duffany SR, et al. Actual and perceived memory deficits in individuals with compulsive hoarding. Depress Anxiety. 2004;20:59–69. doi: 10.1002/da.20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frost RO, Hartl T, Christian R, Williams N. The value of possessions in compulsive hoarding: Patterns of use and attachment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33:897–902. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00043-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steketee G, Frost RO, Kyrios M. Beliefs about possessions among compulsive hoarders. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:467–479. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. An open trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1461–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown TA, DiNardo PA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM- IV. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: implications for the classification of emotional disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frost RO, Steketee G, Grisham J. Measurement of compulsive hoarding: Saving Inventory-Revised. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:1163–82. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. A brief interview for assessing compulsive hoarding: The Hoarding Rating Scale-Interview. Psychiatry Research. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.05.001. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guy W. Assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. 2. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, Harcourt, Brace; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the hehavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steketee G, Frost RO, Wincze J, Greene K, Douglass H. Group and individual treatment of compulsive hoarding: A pilot study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2000;28:259–268. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tolin DF, Fitch KE, Frost RO, Steketee G. Family informants’ perceptions of insight in compulsive hoarding. Cognitive Therapy and Research. in press. [Google Scholar]