Abstract

Influenza A virus particles assemble and bud from plasma membrane domains enriched with the viral glycoproteins but only a small fraction of the total M2 protein is incorporated into virus particles when compared to the other viral glycoproteins. A membrane proximal cholesterol recognition/interaction amino acid consensus (CRAC) motif was previously identified in M2 and suggested to play a role in protein function. We investigated the importance of the CRAC motif on virus replication by generating recombinant proteins and viruses containing amino acid substitutions in this motif. Alteration or completion of the M2 CRAC motif in two different virus strains caused no changes in virus replication in vitro. Viruses lacking an M2 CRAC motif had decreased morbidity and mortality in the mouse model of infection, suggesting that this motif is a virulence determinant which may facilitate virus replication in vivo but is not required for basic virus replication in tissue culture.

Keywords: Influenza, M2 protein, virus assembly, Cholesterol binding, CRAC, Pathogenesis

Introduction

Influenza A virus remains a major public health burden and potential pandemic threat even with widespread annual vaccination and the availability of antivirals. The M2 protein is required for several steps in the viral life cycle (reviewed in (Pinto and Lamb, 2007)). Following hemagglutinin (HA)-mediated virus-cell membrane fusion, the ion-channel activity of M2 is activated in acidified endosomes. M2 translocates protons into the core of the virus particle which mediates the release of viral ribonucleoprotein (vRNP) complexes from their association with matrix (M1) protein and viral membranes. The vRNP are tranported to the nucleus where viral transcription and genome replication occurs. The ion-channel activity of M2 also raises the pH of the Golgi compartment, thereby preventing the low pH induced conformational changes in HA proteins which are processed to their fusion-competent forms by intracellular proteases. Virus particle assembly occurs at the plasma membrane and the cytoplasmic tail of M2 is required for efficient incorporation of vRNP into infectious virus particles (McCown and Pekosz, 2005; McCown and Pekosz, 2006).

Influenza A virus particles assemble and bud from plasma membrane domains enriched with the viral glycoproteins, HA and neuraminidase (NA). These domains may also reflect lipid rafts (Leser and Lamb, 2005; Scheiffele et al., 1999; Zhang, Pekosz, and Lamb, 2000). The cytoplasmic tails of HA and NA bind and recruit M1 to membranes (Ali et al., 2000). Even though M2 is not found at these sites of glycoprotein enrichment, a small amount of M2 is incorporated into virus particles (Leser and Lamb, 2005; Zhang, Pekosz, and Lamb, 2000). Additionally, the amount of M2 incorporation can be increased if the glycoproteins are targeted away from lipid microdomains by the deletion of their cytoplasmic tails (Chen, Takeda, and Lamb, 2005).

Several mechanisms have been hypothesized to contribute to M2 virion incorporation, including random incorporation and incorporation via interaction with cholesterol (Schroeder et al., 2005). A membrane proximal cholesterol recognition/interaction amino acid consensus (CRAC) motif has been identified in the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor and other proteins known to bind cholesterol (Li and Papadopoulos, 1998), including caveolin-1 (Epand, Sayer, and Epand, 2005) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) gp41 (Greenwood et al., 2008; Vincent, Genin, and Malvoisin, 2002; Vishwanathan et al., 2008). The CRAC motif in gp41 is adjacent to a transmembrane helix and has been shown to bind cholesteryl-hemisuccinate agarose (Vincent, Genin, and Malvoisin, 2002). Mutation of the motif decreased cholesterol binding but also altered fusogenic activity when introduced into HIV (Epand et al., 2006; Vishwanathan et al., 2008). Schroeder et al. identified a putative CRAC motif in M2 and determined that M2 protein purified from a baculovirus expression system binds cholesterol (Schroeder et al., 2005). A second CRAC motif immediately downstream of the first one is present in a limited number of influenza virus strains. They suggest that cholesterol-bound M2 protein may be able to either rim or unite lipid microdomains, thereby facilitating M2 incorporation into virions. Because M2 is required during several distinct steps in the virus life cycle, we investigated the importance of the CRAC motif on virus replication by generating recombinant proteins and viruses containing alterations in this motif.

Results

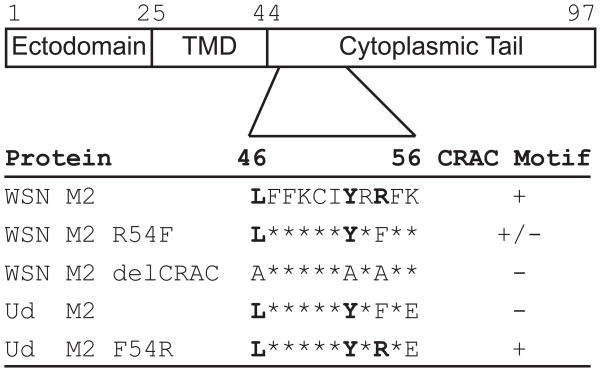

Oligomerization and expression of mutant M2 proteins in stable cell lines

Influenza A/WSN/33 (rWSN) encodes an M2 protein with a consensus (L/V-X(1–5)-Y-X(1–5)-R/K ) CRAC motif ((Jamin et al., 2005; Lacapere and Papadopoulos, 2003; Li and Papadopoulos, 1998; Li et al., 2001), reviewed in (Epand, 2006)) while A/Udorn/72 (rUd) encodes a protein with an R at position 54 which disrupts the consensus (Figure 1). These influenza virus strains do not possess a second putative CRAC domain (Schroeder et al., 2005). Mutations were made in rWSN M2 to alter the CRAC motif by either mutating residue 54 from arginine to phenylalanine (rWSN M2 R54F), the amino acid found in the rUd M2 protein, or changing all of the critical CRAC motif residues to alanine (rWSN M2 delCRAC) in order to eliminate the consensus sequence. Additionally, the CRAC motif in rUd M2 was completed by mutating residue 54 from phenylalanine to arginine (rUd M2 F54R). The WSN M2 proteins also contain an asparagine to serine mutation at residue 31 which conveys amantadine sensitivity (Hay et al., 1985; Takeda et al., 2002) so that the potentially toxic effects of ion channel activity could be inhibited during routine cell culture.

Figure 1. Sequence alignment of M2 residues 46–56.

The amino acids that define the CRAC motif are in bold and substitutions that disrupt or complete the consensus are indicated. An asterisk indicates no change in sequence. The rWSN M2 R54F mutant still contains a potential CRAC consensus sequence due to the presence of another basic amino acid at position 56.

Stably transfected MDCK cell lines were generated which constitutively express the wildtype or mutant M2 proteins. Mutation of the CRAC motif does not affect M2 protein oligomerization as determined by non-reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (Fig 2A and D). To determine if the mutant M2 proteins were expressed at the cell surface, flow cytometry was performed on live cells using an antibody which recognizes the extracellular domain of M2. Greater than 90% of the cells express M2 at the cell surface (Fig 2B and E). The total amount of mutant M2 expressed in the stable cell lines was comparable to a control cell line expressing wildtype M2 protein (Fig 1A and D) as was the amount of M2 expressed at the cell surface (data not shown).

Figure 2. Expression and function of M2 proteins with modified CRAC motifs.

(A and D) MDCK cells expressing the indicated M2 proteins were analyzed by Western blotting to detect disulfide linked oligomeric forms of the M2 protein. Monomers, dimers and trimers are indicated and some higher order oligomers can be detected. (B and E) The number of cells expressing M2 at the cell surface was quantified by flow cytometry from the indicated stably transfected MDCK cell lines. (C and F) The ability of the indicated stably transfected MDCK cells to complement infection with a recombinant influenza virus that does not encode the full length M2 protein was assessed by infecting the cells with the indicated recombinant virus and quantifying infectious virus production at various hours post infection (hpi). The average and standard error of the mean are graphed. The standard error bars are smaller than the size of the individual points. The limit of detection is marked by a dotted line. Proteins or recombinant viruses based on the rWSN (A–C) and rUd virus strains (D–F) were used.

M2 proteins with altered CRAC motifs are able to complement M2 deficient viruses

The M2 protein plays several roles in the virus life cycle and altering any of these functions can drastically reduce virus replication and fitness (Iwatsuki-Horimoto et al., 2006; McCown and Pekosz, 2005; McCown and Pekosz, 2006; Takeda et al., 2002). The ability of stably expressed M2 to complement M2 deficient viruses has been previously used to study mutations in M2 which may prevent the rescue of recombinant viruses (Chen et al., 2008; McCown and Pekosz, 2005; McCown and Pekosz, 2006; Thomas et al., 1998). To determine if M2 proteins with mutations in the CRAC motif are able to complement M2 deficient viruses, stable cell lines expressing M2 were infected with viruses which contain a stop codon in their M2 gene (M2Stop viruses). Neither alteration of the CRAC motif (Fig 2C) nor completion of the CRAC motif (Fig 2F) resulted in a statistically significant change in the production of infectious virus when compared to wt M2, indicating all the mutated M2 proteins are fully functional in this assay.

Alteration of M2 CRAC motif does not affect the replication of recombinant influenza A viruses in tissue culture

In order to confirm that mutation of the CRAC motif in the M2 protein does not affect virus replication, recombinant viruses were generated which encode M2 proteins with mutations in the CRAC motif (Figure 1). Infection of MDCK cells with these viruses results in a similar level of cell surface M2 as determined by flow cytometry (Fig 3A and D). Multistep growth curves in MDCK (Fig 3B and E) and the human lung adenocarcinoma, CaLu-3 cells (Fig 3C and F) results in no statistically significant changes in either replication kinetics or peak infectious virus titers, indicating the recombinant viruses with altered M2 CRAC motifs maintain the ability to replicate in these cell lines.

Fig. 3.

The effects of altering the CRAC motif on replication in tissue culture. (A and D) MDCK cells were infected with the indicated viruses at an MOI of ~3 and the cell surface expression of M2 protein was measured by flow cytometry at 15 hours post infection (hpi). The relative expression of M2 represents the mean channel fluorescence of the indicated infected cells divided by the mean channel fluorescence of the wildtype infected cells. MDCK (B and E) or CaLu-3 (C and F) cells were infected at an MOI of ~0.001 with the indicated recombinant viruses. At the indicated hpi, infected cell supernatants were harvested and the number of infectious virus particles determined by TCID50 assay. Data points represent the average and standard error of the mean. The horizontal dotted line is the limit of detection.

Many primary and some laboratory-adapted influenza A virus strains produce filamentous particles, including rUd, while most laboratory-adapted influenza A virus strains, such as rWSN, produce spherical particles (Mosley and Wyckoff, 1946; Roberts and Compans, 1998; Roberts, Lamb, and Compans, 1998). In order to determine if completion of the CRAC motif in Ud M2 affects the ability of recombinant virus to produce filamentous particles, confocal microscopy was performed to compare the number of infected cells which produce filaments. Filaments formed by both rUd M2 F54R and wildtype were similar in appearance (Fig 4A and B) and the number of infected cells showing filaments was not significantly different (Fig 4C). Additionally, like wildtype rWSN, rWSN M2 R54F and rWSN M2 delCRAC failed to formed filaments on the surface of infected cells (data not shown). In order to determine if the filamentous virus particles were similar in size and structure, transmission electron micrographs were taken of infected MDCK cells. The rUd virus encoding M2 F54R was able to produce filamentous particles like wildtype virus (Fig 4D and E). Together, this data indicates that completion of the CRAC motif does not alter the ability of influenza virus to produce filamentous virus particles.

Fig. 4.

The effects of completing the CRAC motif on formation of filamentous virus particles. MDCK7 cells were infected with 500,000 TCID50 (~0.9 MOI). At 15hpi, immunofluorescence staining was performed for HA and visualized by confocal microscopy. Confocal Z-sections (taken with a 100x objective) of rUd (A) or rUd M2 F54R (B) infected cells were flattened and show viral filaments for both viruses. The percentage of infected cells showing filaments was determined from 10–20 images taken with a 20x objective on an epifluorescence microscope (C). One representative experiment is shown. For TEM, MDCK cells were infected at an MOI of ~5. Samples were processed for transmission electron microscopy at 10 hpi. Cells were infected with rUd (D) or rUd M2 F54R (E). Arrows indicate microvilli, solid arrowheads indicate filamentous virus particles, and empty arrowheads mark either spherical virus particles or cross-sections of filamentous virus particles.

Virion protein composition of recombinant viruses encoding M2 CRAC mutants

In order to investigate the requirement of the CRAC motif for incorporation of viral proteins into virions, virus particles were collected and concentrated through a 20% sucrose cushion by ultracentrifugation. Virus pellets were resuspended and the amount of incorporated viral proteins was determined by Western blot (Fig 5A and B). Relative amounts of full length M2 and total M2 were quantified from replicate experiments. Total M2 incorporated into either CRAC altered or CRAC completed recombinant viruses was not statistically different from wildtype (Fig 5C and D). There was a statistically significant decrease in the amount of truncated M2 protein incorporated into rWSN M2 R54F virions. The truncated form of M2 is thought to be generated via cleavage by caspases at the C-terminus of M2 but this cleavage does not appear to affect viral replication (Zhirnov et al., 2002; Zhirnov and Syrtzev, 2009). Additionally, HA, NP, and M1 were incorporated into virus particles at levels indistinguishable from wildtype M2when the M2 CRAC motif was altered or completed (Fig 5A and B; data not shown).

Fig. 5.

The effects of altering the CRAC motif on incorporation of structural proteins. MDCK cells were infected with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 5. At 15hpi, virus particles were collected and concentrated through a 20% sucrose cushion at 118,000 g for 1hr. Virus pellets were resuspended and incorporation of viral proteins was determined by Western blot with antibodies which detect the structural proteins HA, NP, M1, and M2. (A and B) Representative Western blots showing incorporation of viral proteins into virions. (C and D) Quantification of full length M2 and total M2 from Western blot analysis of replicate virion incorporation assays. A large amount of pelleted virions was loaded onto the SDS-PAGE gel in order to detect the relatively low amounts of incorporated M2 protein. Relative expression was determined by the negative log of M1 normalized data. Recombinant viruses based on the rWSN (A and C) or rUd virus strains (B and D) were used. * = p<0.05.

Decreased morbidity and mortality in mice infected with recombinant viruses expressing M2 CRAC mutants

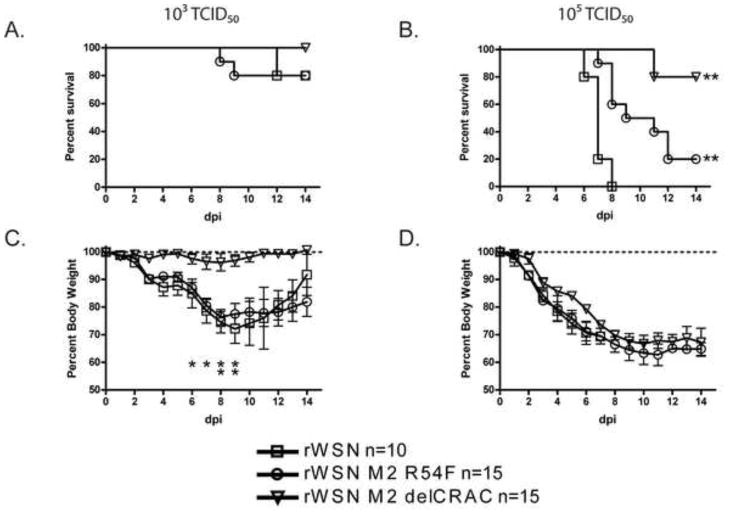

Some M2 mutations have been shown to have no effect in vitro but display decreased in vivo pathogenesis (Grantham et al., 2009; Watanabe et al., 2008; Wu and Pekosz, 2008). In order to determine if mutation of the M2 CRAC motif affects in vivo pathogenesis, mice were infected with rWSN viruses expressing the wildtype M2, M2 R54F, or M2 delCRAC. When intranasally inoculated with 103 TCID50, mice infected with all viruses displayed similar survival (Fig 6A). When mice were infected with 105 TCID50 of virus, rWSN caused significantly more mortality compared to rWSN M2 R54F and rWSN M2 delCRAC (Fig 6B). The median time of death for rWSN (7 days) and rWSN M2 R54F (11 days) differed as well. Change in body mass induced by infection with 103 TCID50 of either rWSN or rWSN M2 R54F was more significant than that induced by rWSN M2 delCRAC (Fig 6C). Mice infected 105 TCID50 of the viruses did not display significant differences in loss of body mass over the first 6 days of infection, despite the decreased mortality of mice infected with the CRAC altered recombinant viruses (Fig 6D). Infection of mice with 105 TCID50 of rUd M2F54R did not result in a significant increase in virus replication or morbidity when compared to rUd, suggesting that restoration of the complete CRAC domain did not enhance in vivo replication of rUd (data not shown). This data indicates that elimination of the M2 CRAC motif leads to a modest attenuation of virus virulence in the mouse model of infection despite no obvious defects in in vitro virus replication.

Fig. 6.

Mortality and morbidity of mice infected with recombinant influenza A/WSN/33 viruses encoding M2 proteins with altered CRAC motifs. Mice were administered an intranasal dose of 103 (A and C) or 105 (B and D) TCID50 of the indicated viruses and monitored for 14 days post infection (dpi). (A and B) Mortality and (C and D) morbidity associated with infection, as judged by loss of starting weight. Data points indicate the average and standard deviation. Significant differences in (B) are between the CRAC altered viruses and rWSN while in (C) the differences are between rWSN M2 delCRAC and the other two viruses. * = p<0.05 and ** = P<0.01.

Alteration of the M2 CRAC motif does not affect replication of recombinant influenza A viruses in mTEC cultures

Given the discrepancy between the ability of the recombinant viruses to replicate in tissue culture cells and their attenuation in the mouse model of infection, we investigated whether virus infection of mTEC cultures would better reflect the in vivo virus phenotypes. These primary cell cultures are differentiated into cell types normally found in the mouse trachea and therefore represent a faithful tissue culture surrogate for virus infection of the airways (Ibricevic et al., 2006b; Newby, Sabin, and Pekosz, 2007; Pekosz et al., 2009). There was no statistically significant difference in the replication of the mutant viruses in mTEC cultures as compared to the corresponding wildtype virus (Fig 7), suggesting that replication in mTEC cultures was not compromised by altering the CRAC motif.

Fig. 7.

The effects of altering the CRAC motif on replication in mouse tracheal epithelial cell (mTEC) cultures. mTEC cultures were infected with 3300 TCID50 (~0.01 MOI) of the indicated recombinant viruses in the rWSN (A) or rUdorn (B) genetic backgrounds. At the indicated hpi, infected cell supernatants were harvested and the number of infectious virus particles determined by TCID50 assay in MDCK cells. Data points represent the average and standard error of the mean. The horizontal dotted line is the limit of detection.

Discussion

This study sought to investigate the role of the CRAC motif found in the M2 protein of two influenza A virus strains. The R54F mutation in the WSN M2 protein was made to mimic the amino acid found at that residue in Ud M2. The rWSN M2 R54F mutant virus still contains a putative consensus CRAC sequence because it has another basic amino acid at residue 56. This could explain why this virus has an intermediate change in virulence when compared to rWSN and rWSN delCRAC. Mutation of WSN M2 to either R54F or delCRAC leads to no changes in virus replication in vitro. Likewise, completion of the CRAC motif in the Ud M2 protein also has no effect on virus replication in MDCK cells, CaLu-3 cells, or in mTEC cultures. Together, this suggests that the CRAC motif is not required for in vitro replication of influenza A virus.

Even though the CRAC motif is not essential for in vitro virus replication, mutation of the motif resulted in decreased morbidity and mortality when mice were infected with a virus lacking the CRAC motif. The decreased pathogenesis of mutants may suggest that the CRAC motif of the M2 protein may be a virulence determinant in that it is not required for in vitro virus replication but is critical for efficient virus infection in animal models. It is also possible that presence of a complete CRAC motif in M2 protein contributes to virus infection of other cell types such as alveolar epithelial cells or macrophages. Rossman et al. recently demonstrated that amino acids outside of the CRAC domain contribute to the cholesterol binding of M2 and mutation of these amino acid sequences leads to decreased in vitro replication (Rossman et al., 2010). The M2 protein only showed cholesterol binding activity in the context of a virus infection and changes at multiple amino acids that line the hydrophobic face of a membrane proximal alpha helix of the protein were demonstrated to be critical for in vitro virus replication. This suggests that the CRAC motif in and of itself, is not required for influenza virus replication in vitro, a fact supported by our data.

The cytoplasmic tail of M2 has been implicated in the stabilization of the open state of the M2 ion channel (Schnell and Chou, 2008; Tobler et al., 1999), virion incorporation of M1 and vRNP (Iwatsuki-Horimoto et al., 2006; McCown and Pekosz, 2005; McCown and Pekosz, 2006), virus morphology (Iwatsuki-Horimoto et al., 2006), and virus infectivity (Chen et al., 2008; Iwatsuki-Horimoto et al., 2006; McCown and Pekosz, 2005; McCown and Pekosz, 2006; Takeda et al., 2002). Although the transmembrane domain of M2 has been studied by NMR and crystallography, the structure of the cytoplasmic domain is less well understood (Schnell and Chou, 2008; Stouffer et al., 2008). The structure of residues 45–60 of the M2 cytoplasmic tail has been determined by NMR in concert with the transmembrane domain (Schnell and Chou, 2008), but the structure of the entire cytoplasmic tail has yet to be determined. Residues 47–50 form a short, flexible loop linking the transmembrane domain to a C-terminal amphipathic helix (residues 51–59) that forms a stable “base” important for holding the tetramers together during the conformational changes associated with ion channel activation. The CRAC domain and a site for palmitoylation (Ser 50) fall into these regions and it has been speculated that these modifications may stabilize the interaction of the M2 cytoplasmic tail with lipid membranes (Schnell and Chou, 2008). Elimination of the CRAC motif or the M2 palmitoylation site (Grantham et al., 2009) does not alter virus replication in vitro, but does yield viruses that are attenuated in the mouse model of infection. This data argues against a critical role for these two sequences in virus replication, though both sequences are essential for maintaining virus virulence in vivo. While these sequences may be dispensable for virus replication, this does not imply that this region of the M2 protein is not important for M2 function either as a structural motif, or through properties as yet undefined.

The CRAC motif in the M2 protein is not required for incorporation of M2 into virions, nor does it affect the incorporation of other viral proteins. Alternate methods mediating the incorporation of M2 into virions must therefore exist. One study suggests that the ectodomain of M2 can drive a foreign protein to be incorporated into influenza A virus particles (Park et al., 1998) but there are no known interactions between the M2 ectodomain and the ectodomains of the other viral glycoproteins. The mechanism by which a limited amount of M2 is incorporated into virus particles despite the high amounts of M2 located in the plasma membrane but not in the same membrane microdomains as the glycoproteins remains to be determined.

Materials & Methods

Plasmids

The plasmid pCAGGS (Niwa, Yamamura, and Miyazaki, 1991) was used for M2 expression in mammalian cells. A plasmid expressing the M2 cDNA from influenza A/Udorn/72 (Ud M2) has been described previously (McCown and Pekosz, 2005). The M2 coding region from influenza A/WSN/33 (Genebank Accession number ABF21317) was amplified by RT-PCR and cloned as described previously for M2 Ud (McCown, Diamond, and Pekosz, 2003). A WSN M2 cDNA encoding a protein sensitive to the antiviral drug amantadine was constructed by changing the amino acid at position 31 from arginine to serine (N31S) (Takeda et al., 2002). All M2 mutations were introduced into the expression plasmids by overlap extension PCR and the sequences of the mutated plasmids were confirmed. Primer sequences are available upon request.

The pBABE plasmid, which expresses puromycin N-acetyltransferase, was used to generate stable cell lines expressing mutant M2 proteins as previously described (Morgenstern and Land, 1990).

In order to generate recombinant influenza viruses expressing M2 proteins with altered CRAC motifs, mutations were introduced into the pHH21 M segment plasmids via site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene). The sequence of the entire M segment of the resulting plasmid was confirmed.

Cells

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, human lung adenocarcinoma (CaLu-3) cells (ATCC HTB-55), and human embryonic kidney (293T) cells (Takeda et al., 2002) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals), 100U/mL penicillin (Invitrogen), 100μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen), 1mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma), and 2mM GlutaMAX (Invitrogen). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 environment.

Generation of stable cell lines

MDCK cells stably expressing M2 proteins were generated as described previously (McCown and Pekosz, 2005). Briefly, MDCK cells were cotransfected in suspension with 1μg pCAGGS M2 expression plasmid and 0.5μg pBABE puromycin expression plasmid using 9μL of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were plated into 6 well plates, selected using 7.5μg/mL puromycin dihydrochloride (Sigma), and single colonies were isolated and expanded. Expression of M2 was confirmed by indirect immunofluorescence staining of surface M2 using monoclonal antibody (MAb) 14C2. M2 expressing cells were maintained with 5μM amantadine hydrochloride (Sigma).

Viruses

The viruses used in this study were rWSN and rUd (recombinant versions of A/WSN/33 and A/Udorn/72, respectively). Viruses were generated using a 12-plasmid rescue system described previously (McCown and Pekosz, 2005; McCown and Pekosz, 2006; Neumann et al., 1999; Takeda et al., 2002). The entire coding region of the M segment sequence of all rescued viruses was confirmed. There were no discernable differences in plaque size or morphology between any of the recombinant viruses (data not shown).

Virus growth curves were performed at a multiplicity-of-infection (MOI) of ~0.001. For complementation assays, MDCK cells expressing mutant M2 proteins were infected with recombinant viruses that were functionally deleted for the expression of M2 (M2stop viruses) as described previously (McCown and Pekosz, 2006). For recombinant viruses, mutant M2-expressing viruses were used to infect MDCK or CaLu-3 cells. Cells were infected by twice washing confluent 6 well plates of MDCKs with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Invitrogen) then infecting with the indicated viruses in 500μL infectious media (DMEM supplemented with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Calbiochem), 100U/mL penicillin, 100μg/mL streptomycin, 2mM GlutaMAX, and 4μg/mL N-acetyl trypsin (NAT, Sigma)) at room temperature with rocking for 1hr. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and incubated with 500μL infectious media. Media was removed and replaced with fresh media at the indicated timepoints. Infectious virus titers were quantified by determining the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) on MDCK cells (for M2-expressing viruses) or MDCK cells expressing WSN M2 N31S (for M2Stop viruses). Media lacking trypsin was used for infection of CaLu-3 cells. Standard error of the mean is graphed from infections done in duplicate or triplicate. The experiments were repeated at least twice and one representative example is graphed.

For microscopy, MDCK cells were grown to confluency on tissue culture treated glass coverslips and media changed every 2 days. Four days after confluence, cells were washed twice with PBS, infected with 500,000 TCID50 (~0.9 MOI) of the indicated virus in 500μL medium for 1 hr at room temperature. Cells were then washed, the media was replaced and the cells incubated at 37C for 15 hours.

Virus purification

Virus particles were isolated from the supernatants of MDCK cells infected at an MOI of 5 for 15hr. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 1,900 g for 10min at 4°C. Virus particles were then concentrated through a 20% sucrose cushion with centrifugation at 118,000 g in a TH641 rotor (Sorval) for 1hr at 4°C. Virus pellets were resuspended in 100μL PBS and mixed 1:1 in 2x SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

MDCK cells were lysed in 1% SDS (Fisher Scientific) in PBS and mixed 1:1 in 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Polypeptides were resolved on 17.5% polyacrylamide gel with 4M urea and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (PVDF, Millipore). Membranes were blocked with PBS containing 0.3% Tween-20 (Sigma) and 5% dry milk, incubated 1hr RT with primary antibody, washed three times with PBS with 0.3% Tween-20, incubated 1hr RT with secondary antibody, and washed four times with PBS containing 0.3% Tween-20. The primary antibodies used were mouse α-M2 14C2 MAb (1:1,000 dilution) (Zebedee and Lamb, 1988), mouse α-M1 HB-64 MAb (1:100 dilution) (McCown and Pekosz, 2005; Yewdell, Frank, and Gerhard, 1981), mouse α-NP HB-65 MAb (1:100 dilution) (McCown and Pekosz, 2005; Yewdell, Frank, and Gerhard, 1981), goat α-A/Udorn/72 serum (1:500 dilution) (Zhang, Pekosz, and Lamb, 2000), or goat α-HA0 A/PR/8/34 (1:500 dilution, V-314-511-157; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases). Secondary antibodies were goat α-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated to AlexaFluor 647 (4μg/mL, Invitrogen), donkey α-mouse IgG conjugated to AlexaFluor 647 (4μg/mL, Invitrogen), donkey α-goat IgG conjugated to AlexaFluor 647 (4μg/mL, Invitrogen). Membranes where then scanned using an FLA-5000 (FujiFilm), samples were normalized to total M1 and M2 expression relative to wild type protein was determined. Structural proteins and oligomeric forms of M2 are indicated.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were removed from the tissue culture plates with trypsin treatment. The trypsin was inactivated with serum containing media and cells were washed once with PBS and incubated on ice for 30min, in the presence of blocking buffer (PBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA and 3% normal goat serum (NGS, Sigma)). Cells were then incubated for 1hr on ice with an antibody that recognizes the M2 ectodomain (14C2 MAb, 1:1000 dilution), washed three times with PBS, incubated with goat α-mouse IgG conjugated to AlexaFluor 488 (4μg/mL, Invitrogen) for 1hr on ice, and washed three times with PBS. Cells were then fixed with 1% formaldehyde (Fisher Scientific) in PBS for 15min at room temperature. The cells were analyzed on a FACSCalibur (Beckton Dickinson) and quantified using FlowJo software (Tree Star). All antibody dilutions were made in blocking buffer.

Microscopy

The cells were treated as for flow cytometry except antibodies were goat α-H3 sera raised against A/Aichi/2/68 (1:500 dilution, V-314-591-157; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases) and donkey α-goat IgG conjugated to AlexaFluor 555 (4μg/mL, Invitrogen). After incubation with antibodies, the cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) in PBS for 15min at room temperature, washed twice with PBS, then mounted on slides using ProLong Gold anti-fade (Invitrogen).

Samples were imaged on a Nikon Eclipse 90i microscope. For quantification, 10 or 20 images of random fields of view were taken with a 20x objective in two separate experiments. For each image, the number of infected cells and cells with filaments were counted and used to determine the percentage of infected cells expressing filaments. Data from one representative experiment is shown. For high magnification images, Z-sections were taken at 0.3μm intervals on a Leica 510 Meta LSM confocal microscope using a 100x oil-immersion lens. Volocity 3D imaging software (Improvision) was used to analyze and flatten Z-sections.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

MDCK cells were grown to confluency in 3.5cm dishes and infected at an MOI of ~5 with either rUd or rUd M2 F54R. At 10hpi, cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 2mL of fresh fixative (2% glutaraldehyde, 0.1M cacodylate, 3% sucrose, and 3mM CaCl2 in PBS pH7.4) overnight at 4°C. Cells were post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide reduced in potassium ferrocyanide for 1 hr at 4°C. After fixation, cells were stained en bloc with a 2% aqueous solution of uranyl acetate and dehydrated in graded ethanol. Embedding was done in Eponate 12 Resin (Ted Pella). Thin sections (70–90nm) were cut on a Reichert-Jung Ultracut E and placed on 200 mesh copper grids. The sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and viewed on a Hitachi 7600 TEM with an AMT digital camera.

Infection of BALB/c mice

Six to 8-week old female BALB/c mice (Charles River) were used as described previously (Newby, Sabin, and Pekosz, 2007; Wu and Pekosz, 2008). Mice were anesthetized and administered an intranasal inoculation of 103 or 105 TCID50 of rWSN, rWSN M2 R54F, or rWSN M2 delCRAC virus diluted in 20μL DMEM supplemented with 100U/mL penicillin, 100μg/mL streptomycin, and 4μg/mL NAT. Animals were monitored for 14 dpi for morbidity and mortality (Wu and Pekosz, 2008). Changes in body mass are graphed as percent of starting mass.

Infection of mTEC cultures

Mouse tracheal epithelial cells (mTECs) were harvested, isolated, and differentiated as described previously (Ibricevic et al., 2006a; Newby, Sabin, and Pekosz, 2007). Cultures were infected via the apical chamber with 3,300 TCID50 in 100μL of media, ~0.01 MOI assuming all cells are susceptible to infection. After 1hr, apical supernatants were removed and replaced with fresh media. At the indicated hpi, apical and basolateral supernatants were removed and replaced with fresh media. Throughout the infection, infectious media without NAT was used. Infectious virus titers were quantified at indicated times as above. Standard error of the mean is graphed from infections done in duplicate.

Statistical Analysis

Infectious virus production and body mass changes were analyzed using mixed ANOVAs with time and virus as the independent variables. Protein concentrations and differences in the percentage of cells with filaments were calculated using t-tests. Mean day of death was determined by logrank test. Significant interactions were further evaluated using the Tukey method for pairwise multiple comparisons. Statistically significant differences of p<0.05 (*) or p<0.01 (**) are indicated and all analyses were done with Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Becton Dickinson Immune Function Laboratory for flow cytometry assistance, Carol Cooke from the Dept. of Cell Biology Microscope Facility at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine for assistance with TEM, and the members of the Pekosz laboratory for insightful comments and discussions.

This study was supported by T32 GM007067 (SMS), AI053629 (AP), the Eliasberg Foundation (AP), and the Marjorie Gilbert Foundation (AP).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Shaun M Stewart, Email: shstewar@jhsph.edu.

Wai-Hong Wu, Email: wwu@jhsph.edu.

Erin N Lalime, Email: elalime@jhsph.edu.

Andrew Pekosz, Email: apekosz@jhsph.edu.

References

- Ali A, Avalos RT, Ponimaskin E, Nayak DP. Influenza virus assembly: effect of influenza virus glycoproteins on the membrane association of M1 protein. J Virol. 2000;74(18):8709–19. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8709-8719.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BJ, Leser GP, Jackson D, Lamb RA. The Influenza Virus M2 Protein Cytoplasmic Tail Interacts with the M1 Protein and Influences Virus Assembly at the Site of Virus Budding. J Virol. 2008;82(20):10059–10070. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01184-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BJ, Takeda M, Lamb RA. Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin (H3 Subtype) Requires Palmitoylation of Its Cytoplasmic Tail for Assembly: M1 Proteins of Two Subtypes Differ in Their Ability To Support Assembly. J Virol. 2005;79(21):13673–13684. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13673-13684.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand RF, Thomas A, Brasseur R, Vishwanathan SA, Hunter E, Epand RM. Juxtamembrane Protein Segments that Contribute to Recruitment of Cholesterol into Domains. Biochemistry. 2006;45(19):6105–6114. doi: 10.1021/bi060245+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand RM. Cholesterol and the interaction of proteins with membrane domains. Progress in Lipid Research. 2006;45(4):279–294. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand RM, Sayer BG, Epand RF. Caveolin Scaffolding Region and Cholesterol-rich Domains in Membranes. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2005;345(2):339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham ML, Wu W-H, Lalime EN, Lorenzo ME, Klein SL, Pekosz A. Palmitoylation of the influenza A virus M2 protein is not required for virus replication in vitro but contributes to virus virulence. J Virol. 2009:JVI.01129–09. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01129-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood AI, Pan J, Mills TT, Nagle JF, Epand RM, Tristram-Nagle S. CRAC motif peptide of the HIV-1 gp41 protein thins SOPC membranes and interacts with cholesterol. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2008;1778(4):1120–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay AJ, Wolstenholme AJ, Skehel JJ, Smith MH. The molecular basis of the specific anti-influenza action of amantadine. Embo J. 1985;4(11):3021–4. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibricevic A, Pekosz A, Walter MJ, Newby C, Battaile JT, Brown EG, Holtzman MJ, Brody SL. Influenza Virus Receptor Specificity and Cell Tropism in Mouse and Human Airway Epithelial Cells. J Virol. 2006a;80(15):7469–7480. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02677-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibricevic A, Pekosz A, Walter MJ, Newby C, Battaile JT, Brown EG, Holtzman MJ, Brody SL. Influenza virus receptor specificity and cell tropism in mouse and human airway epithelial cells. J Virol. 2006b;80(15):7469–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02677-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Horimoto T, Noda T, Kiso M, Maeda J, Watanabe S, Muramoto Y, Fujii K, Kawaoka Y. The Cytoplasmic Tail of the Influenza A Virus M2 Protein Plays a Role in Viral Assembly. J Virol. 2006;80(11):5233–5240. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00049-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamin N, Neumann JM, Ostuni MA, Vu TKN, Yao ZX, Murail S, Robert JC, Giatzakis C, Papadopoulos V, Lacapere JJ. Characterization of the Cholesterol Recognition Amino Acid Consensus Sequence of the Peripheral-Type Benzodiazepine Receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(3):588–594. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacapere JJ, Papadopoulos V. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor: structure and function of a cholesterol-binding protein in steroid and bile acid biosynthesis. Steroids. 2003;68(7–8):569–585. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(03)00101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leser GP, Lamb RA. Influenza virus assembly and budding in raft-derived microdomains: A quantitative analysis of the surface distribution of HA, NA and M2 proteins. Virology. 2005;342(2):215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Papadopoulos V. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor function in cholesterol transport. Identification of a putative cholesterol recognition/interaction amino acid sequence and consensus pattern. Endocrinology. 1998;139(12):4991–7. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.12.6390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Yao Z-x, Degenhardt B, Teper G, Papadopoulos V. Cholesterol binding at the cholesterol recognition/interaction amino acid consensus (CRAC) of the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor and inhibition of steroidogenesis by an HIV TAT-CRAC peptide. PNAS. 2001;98(3):1267–1272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031461598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCown M, Diamond MS, Pekosz A. The utility of siRNA transcripts produced by RNA polymerase i in down regulating viral gene expression and replication of negative- and positive-strand RNA viruses. Virology. 2003;313(2):514–524. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCown MF, Pekosz A. The Influenza A Virus M2 Cytoplasmic Tail Is Required for Infectious Virus Production and Efficient Genome Packaging. J Virol. 2005;79(6):3595–3605. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3595-3605.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCown MF, Pekosz A. Distinct Domains of the Influenza A Virus M2 Protein Cytoplasmic Tail Mediate Binding to the M1 Protein and Facilitate Infectious Virus Production. J Virol. 2006;80(16):8178–8189. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00627-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern JP, Land H. Advanced mammalian gene transfer: high titre retroviral vectors with multiple drug selection markers and a complementary helper-free packaging cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18(12):3587–96. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosley VM, Wyckoff RWG. Electron micrography of the virus of influenza. Nature. 1946;157:263. doi: 10.1038/157263a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann G, Watanabe T, Ito H, Watanabe S, Goto H, Gao P, Hughes M, Perez DR, Donis R, Hoffmann E, Hobom G, Kawaoka Y. Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(16):9345–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby CM, Sabin L, Pekosz A. The RNA Binding Domain of Influenza A Virus NS1 Protein Affects Secretion of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha, Interleukin-6, and Interferon in Primary Murine Tracheal Epithelial Cells. J Virol. 2007;81(17):9469–9480. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00989-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108(2):193–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EK, Castrucci MR, Portner A, Kawaoka Y. The M2 Ectodomain Is Important for Its Incorporation into Influenza A Virions. J Virol. 1998;72(3):2449–2455. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2449-2455.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekosz A, Newby C, Bose PS, Lutz A. Sialic acid recognition is a key determinant of influenza A virus tropism in murine trachea epithelial cell cultures. Virology. 2009;386(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto LH, Lamb RA. Controlling influenza virus replication by inhibiting its proton channel. Molecular BioSystems. 2007;3(1):18–23. doi: 10.1039/b611613m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts PC, Compans RW. Host cell dependence of viral morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(10):5746–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts PC, Lamb RA, Compans RW. The M1 and M2 proteins of influenza A virus are important determinants in filamentous particle formation. Virology. 1998;240(1):127–37. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossman JS, Jing X, Leser GP, Balannik V, Pinto LH, Lamb RA. Influenza Virus M2 Ion Channel Protein Is Necessary for Filamentous Virion Formation. J Virol. 2010;84(10):5078–5088. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00119-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiffele P, Rietveld A, Wilk T, Simons K. Influenza viruses select ordered lipid domains during budding from the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(4):2038–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell JR, Chou JJ. Structure and mechanism of the M2 proton channel of influenza A virus. Nature. 2008;451(7178):591–595. doi: 10.1038/nature06531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder C, Heider H, Moncke-Buchner E, Lin TI. The influenza virus ion channel and maturation cofactor M2 is a cholesterol-binding protein. Eur Biophys J. 2005;34 (1):52–66. doi: 10.1007/s00249-004-0424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouffer AL, Acharya R, Salom D, Levine AS, Di Costanzo L, Soto CS, Tereshko V, Nanda V, Stayrook S, DeGrado WF. Structural basis for the function and inhibition of an influenza virus proton channel. Nature. 2008;451(7178):596–599. doi: 10.1038/nature06528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda M, Pekosz A, Shuck K, Pinto LH, Lamb RA. Influenza A virus M2 ion channel activity is essential for efficient replication in tissue culture. J Virol. 2002;76 (3):1391–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1391-1399.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JM, Stevens MP, Percy N, Barclay WS. Phosphorylation of the M2 protein of influenza A virus is not essential for virus viability. Virology. 1998;252(1):54–64. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler K, Kelly ML, Pinto LH, Lamb RA. Effect of Cytoplasmic Tail Truncations on the Activity of the M2 Ion Channel of Influenza A Virus. J Virol. 1999;73(12):9695–9701. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9695-9701.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent N, Genin C, Malvoisin E. Identification of a conserved domain of the HIV-1 transmembrane protein gp41 which interacts with cholesteryl groups. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2002;1567:157–164. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00611-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishwanathan SA, Thomas A, Brasseur R, Epand RF, Hunter E, Epand RM. Hydrophobic Substitutions in the First Residue of the CRAC Segment of the gp41 Protein of HIV. Biochemistry. 2008;47(1):124–130. doi: 10.1021/bi7018892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Watanabe S, Kim JH, Hatta M, Kawaoka Y. Novel Approach to the Development of Effective H5N1 Influenza A Virus Vaccines: Use of M2 Cytoplasmic Tail Mutants. J Virol. 2008;82(5):2486–2492. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01899-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W-H, Pekosz A. Extending the Cytoplasmic Tail of the Influenza A Virus M2 Protein Leads to Reduced Virus Replication In Vivo but Not In Vitro. J Virol. 2008;82(2):1059–1063. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01499-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yewdell JW, Frank E, Gerhard W. Expression of influenza A virus internal antigens on the surface of infected P815 cells. J Immunol. 1981;126(5):1814–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebedee SL, Lamb RA. Influenza A virus M2 protein: monoclonal antibody restriction of virus growth and detection of M2 in virions. J Virol. 1988;62(8):2762–72. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2762-2772.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Pekosz A, Lamb RA. Influenza virus assembly and lipid raft microdomains: a role for the cytoplasmic tails of the spike glycoproteins. J Virol. 2000;74 (10):4634–44. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4634-4644.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhirnov OP, Konakova TE, Wolff T, Klenk HD. NS1 Protein of Influenza A Virus Down-Regulates Apoptosis. J Virol. 2002;76(4):1617–25. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1617-1625.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhirnov OP, Syrtzev VV. Influenza virus pathogenicity is determined by caspase cleavage motifs located in the viral proteins. J Mol Genet Med. 2009;3(1):124–32. doi: 10.4172/1747-0862.1000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]