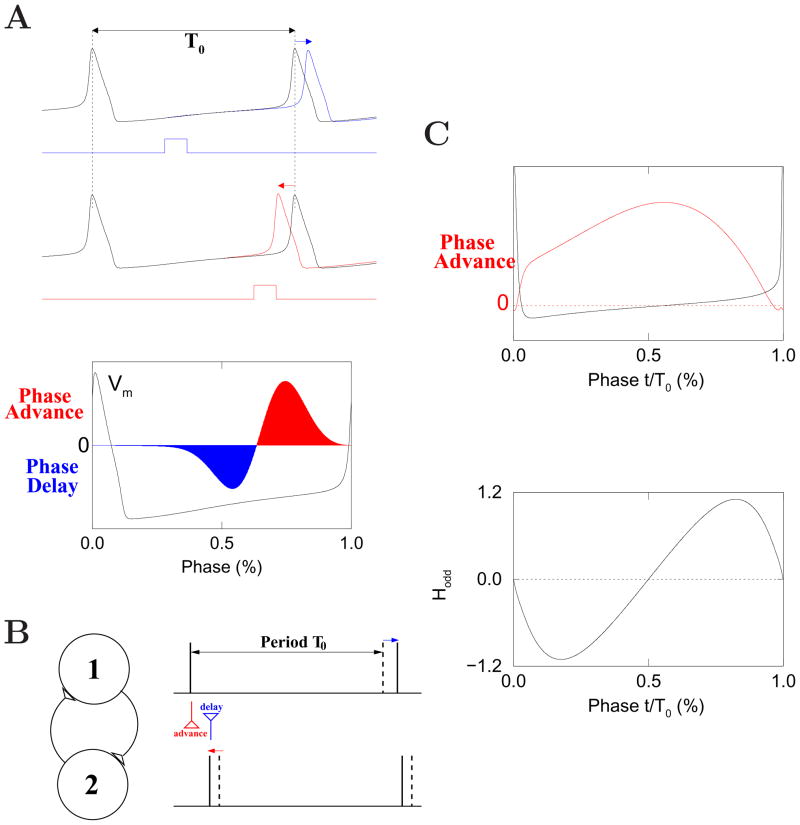

Figure 2. Theory of coupled oscillators.

(A) Phase response curve of the classical (type II) Hodgkin-Huxley model of action potential [437]. Top: a small and brief depolarizing current pulse leads to either a phase delay (blue) or phase advance (red), depending on the timing of the pulse perturbation. T0 is the oscillation period in the absence of perturbation. Bottom: induced phase change (positive for advance, negative for delay) as a function of the oscillatory phase at which the pulse perturbation is applied. Superimposed is the membrane potential for a full oscillation cycle (spike peak corresponds to zero phase). (B) Fast mutual excitation naturally gives rise to synchrony for two coupled Hodgkin-Huxley model neurons, as a cell firing slightly earlier advances the firing of the other cell, while the synaptic input back from the other cell delays its own firing, leading to reduced phase difference between the two in successive cycles. Dashed vertical lines: spike times for isolated neurons. Solid lines: actual spike times in the presence of synaptic interaction. (C) Perfect synchronization by mutual inhibition. Top: phase response curve of a modified (type I) Hodgkin-Huxley model [1035], which does not exhibit significant phase delay (the negative lobe). Bottom: the phase reduction theory predicts the behavior of coupled neurons by the function Hodd(Φ), where Φ is the phase difference between the two neurons (Eq. 4). Hodd was computed using a synapse model with a reversal potential of −75 mV and a decay time constant of 10 ms. Steady state behaviors correspond to Φ values such that Hodd(Φ) = 0. In this example, zero-phase synchrony (Φ = 0) is stable (where Hodd has a negative slope); 180 degree antiphase is unstable (where Hodd has a positive slope).