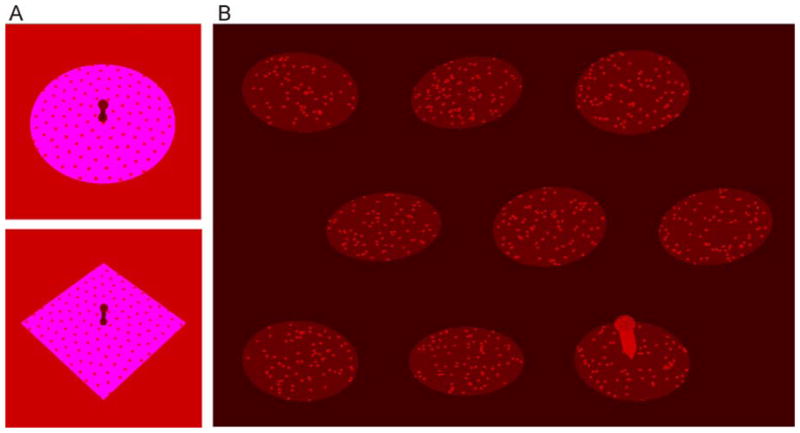

Figure 2.

Stimuli. In all experiments, subjects viewed stimuli binocularly and used the computer mouse to adjust a virtual probe to be perpendicular to a slanted virtual surface. (A) Experiment 1 used ellipse and diamond stimuli, presented at screen center. Experiments 2 and 3 used ellipse stimuli drawn in purple and pink. Of the 146 stimuli presented per experimental block, 96 were “context stimuli” that could either all have an aspect ratio of 1 or have random aspect ratios. The remaining 50 stimuli were “test stimuli” used to calculate the relative influence of the compression cue on subjects’ slant judgments. Test stimuli contained ±5° cue conflicts between the slant suggested by the compression cue under the assumption that the figure has an aspect ratio of 1 and the slant suggested by stereoscopic disparities. (B) In Experiment 4, 9 ellipses, slanted at different angles, appeared at the same time in the display. The probe appeared consecutively on all ellipses. Of the 9 ellipses, 7 were context stimuli. In half of the trials (regular context), they were slanted circles, in the other half (random context), they were slanted ellipses with random aspect ratios. The remaining 2 ellipses were test stimuli. Subjects adjusted the probe for 5 of the context stimuli first and then for the remaining 2 context stimuli and 2 test stimuli in random order. In Experiment 5, the stimuli that were on the screen at the same time in Experiment 4 appeared sequentially. (Note: As it becomes evident particularly from the image of the slanted square diamond in Figure 2A, there are other figural cues (apart from the compression cue) that can be used to infer slant. For example, the distance from the base of the probe to the top vertex of the diamond is smaller than that to the bottom vertex. Under the (constrained) prior assumption that the figure is symmetric about its two main axes and the probe base coincides with surface center, the ratio of these distances provides a perspective ratio cue to slant. Similarly, changes in random dot density provide a texture cue to slant. In our stimuli, the slant suggested by these other perspective cues is always consistent with the slant suggested by the compression cue. Thus, what we refer to as “influence of the compression cue” is really an indicator of how strongly subjects rely on all figural cues, not just the compression cue. There are two reasons to assume that the compression cue dominates the other cues. First, with the stimuli and slants used, changes in slant lead to much larger relative changes in the aspect ratios of figures than in the other cues (e.g. at the small stimulus sizes used in Experiments 4 and 5, the aspect ratio of a circle displayed at 35° slant is 5.7% larger than the aspect ratio of a circle projected at 40° slant, while the perspective ratio changes by only 0.5%. At the larger stimulus sizes in Experiments 1–3, the perspective ratio still changes by only 1.7%). Second, previous studies suggested that in the kinds of displays used here, the visual system gives much more weight to the aspect ratio cue than to these other cues. Studies of slant from texture for random dot textures showed that texture density contributes minimally to slant judgments (Knill, 1998a,b,c). In another study (Knill, 2007a) using the same elliptical stimuli as in Experiments 1–3, but in which cue conflicts were constructed such that the other perspective cues agreed with the disparity cues, subjects gave almost as much weight to the compression cue alone as found here for the combination of figural cues.)