Abstract

Background

Incidence rates of travellers' diarrhoea (TD) need to be updated and risk factors are insufficiently known.

Methods

Between July 2006 and January 2008 adult customers of our Centre for Travel Health travelling to a resource-limited country for the duration of 1 to 8 weeks were invited to participate in a prospective cohort study. They received one questionnaire pre-travel and a second one immediately post-travel. First two-week incidence rates were calculated for TD episodes and a risk assessment was made including demographic and travel-related variables, medical history and behavioural factors.

Results

Among the 3100 persons recruited, 2800 could be investigated, resulting in a participation rate of 89.2%. The first two-weeks incidence for classic TD was 26.2% (95%CI 24.5-27.8). The highest rates were found for Central Africa (29.6%, 95% CI 12.4-46.8), the Indian subcontinent (26.3%, 95%CI 2.3-30.2) and West Africa (21.5%, 95%CI 14.9-28.1). Median TD duration was 2 days (range 1-90). The majority treated TD with loperamide (57.6%), while a small proportion used probiotics (23.0%) and antibiotics (6.8%). Multiple logistic regression analysis on any TD to determine risk factors showed that a resolved diarrhoeal episode experienced in the 4 months pre-travel (OR 2.03, 95%CI 1.59-2.54), antidepressive comedication (OR 2.11, 95%CI 1.17-3.80), allergic asthma (OR 1.67, 95%CI 1.10-2.54), and reporting TD-independent fever (OR 6.56, 95%CI 3.06-14.04) were the most prominent risk factors of TD.

Conclusions

TD remains a frequent travel disease, but there is a decreasing trend in the incidence rate. Patients with a history of allergic asthma, pre-travel diarrhoea, or of TD-independent fever were more likely to develop TD while abroad.

Background

Travellers' diarrhoea (TD), the most common health problem in visitors to tropical and subtropical destinations, affects between 20 to over 60% of persons during a two weeks stay in a high risk country such as India or Kenya [1-3]. As many of those data have been generated some decades ago, the aim of this study is to provide updated region-based TD incidence rates, and to investigate risk factors.

Methods

Study design

Based on a protocol approved by the Ethical Commission of the Canton of Zurich, we performed a prospective questionnaire-based cohort study.

Study population

Potential participants were recruited at the Centre for Travel Health of the University of Zurich between July 2006 and January 2008. To be included, participants had to be adult, German-speaking Swiss residents who planned to travel to high-risk TD destinations [2,4] for a duration of 1 to 8 weeks. Subjects planning to take prophylactic antibiotics during their trip, those who reported a history of severe illness (anaemia, cancer, immunodeficiency or immunosuppressive disorders, severe psychiatric illness, previous gastrointestinal surgery), with functional organic gastrointestinal disorders (according to Rome II [5]/Rome III [6] criteria), or recurring diarrhoeal symptoms within a four months pre-travel period, and pregnant women were excluded.

Definitions

Classic TD was defined as three or more unformed stools per 24 h with at least one accompanying symptom (nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, tenesmus, fever, blood in stools)[7,8], while 3 or more unformed stools with or without additional symptom(s) was named TD based on the UNICEF/WHO definition [9,10]. Patients experiencing one or two loose stools per 24 h while abroad were classified as having mild diarrhoea [8,10]. TD and classic TD were used for incidence calculations in the first two weeks of stay abroad and only TD for multiple logistic regression analysis. TD patients, who reported fever or blood in their stools were rated as having dysentery. Multiple episodes of TD had to be separated by a TD-free interval of at least 72 hours. Incapacitation meant an inability to pursue planned travel activities and was rated in 3 subgroups; low incapacitation could pursue all activities, and severe was defined by being confined to bed for at least 12 hours or by consulting a doctor [4,7]. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated from participants' height and weight data at enrolment. Origin was the country in which the participant spent the first five years of life. 'Newcomers' were visiting the index travel region for the first time. Countries and subcontinents were grouped according to the United Nations World Migrant Stock [11]. Comedication and diseases were classified according to the main categories of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10 2007)[12]. Allergies formed a separate disease entity including allergic asthma, allergic rhinitis, hymenoptera and atopic dermatitis, those were self-reported by the study participant, but an MD confirmation or diagnosis was requested.

Study conduct

Participants who visited our Centre for Travel Health for standard pre-travel consultation were invited to participate in the study on a voluntary basis. Pre-travel advice regarding TD included an explanation of TD etiology, mode of pathogen transmission, preventive behaviour, treatment options and, if indicated, written instructions on how to use antibiotics. A leaflet on general medications (including such against TD) was provided as part of a travel medical kit. Upon signing an informed consent, the participants received two questionnaires. Q1 was collected immediately upon completion, while Q2 was to be returned in the first week after their return reminded either by mail or email; Q2 was similar to a diary.

Q1 included 30-structured questions to assess the itinerary, previous travel to the tropics, demographic data, body mass index, chronic diseases, confirmed allergies, and pre-travel diarrhoea characteristics. In addition, adverse life events in the preceding 12 months, self-reported stress, smoking habits and alcohol consumption, and perceived susceptibility to diarrhoea were investigated.

Q2 consisted of 17-questions to confirm the travel itinerary and to document a detailed history of TD abroad, including TD medication used. After an initial trial phase of three months we added questions about syndromes abroad (health impairments reported abroad, i.e. TD independent fever) and attitudes towards diarrhoea (catering, adherence to 'cook it, boil it, peel it or forget it', tap water consumption) [13,14]. Non-responders were reminded by mail twice; patients reporting uncured diarrhoea were followed until resolution. Those who refused to respond to Q2 were interviewed with the single question whether they had experienced diarrhoea while abroad. No stool samples were collected in this study.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using Stata statistical software, version 10.1 (Stata).

The 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the incidence rates in various subcontinents were estimated as per Newcombes' exact (not approximative) method [15]. We compared differences in proportions of demographics, attitudes and clinical variables using the chi square tests. The significance level was set at α (alpha) = 0.05. All travel- and traveller-related risk factors were evaluated as independent potential risk factors for the development of TD in a multiple logistic regression model. Odds ratios (OR) were determined by stepwise backward elimination of variables with p > 0.100. For the multiple logistic regression analysis only, the later inserted question referring to TD-independent fever was analysed by imputing with organising the missing data using the pattern of gender, destination continent and education. Single imputation by regression imputes for cases with missing values on a variable instead of mean values of this variable function values for this variable out of a regression equation with the following independent variables: education, gender and destination. For the sensitivity tests, the results of the multiple analysis of the complete dataset were compared first to a selection of half of the data and second, to the classic TD definition.

Results

Demographics

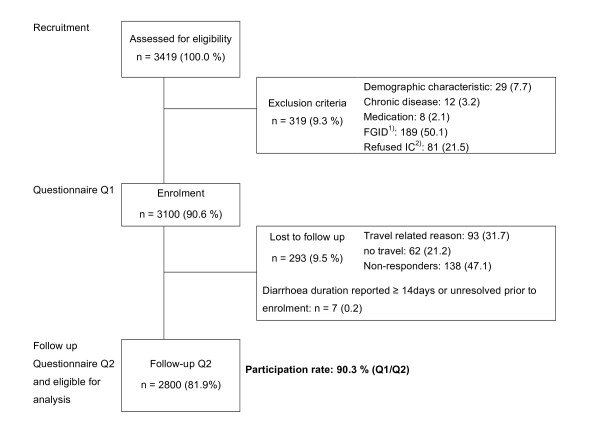

Among 3100 enrolled travellers, 2800 (90.3%) were eligible for analysis (figure 1). Gender was approximately equally distributed (Table 1). Mean age was 38.8 ± 12.6 years (median 35) and half of the population (1403, 51.1%) had a university degree, with significant higher proportions among the business travellers (p = 0.0057). Mean travel duration was 3.2 weeks with the most frequently visited destinations being Southeast (SE) Asia (636, 22.7%), followed by East Africa (522, 18.6%), the Indian subcontinent (476, 17.0%) and South America (435,15.5%). The classic TD and all TD incidence rates for various regions are shown in figure 2 with the highest rates reported in most parts of Africa and on the Indian subcontinent. The largest group of travellers were tourists (1539; 87.9%), while 121 (10.8%) went for business; 90 (5.1%) visited friends and relatives (VFR). The median travel time for business was 2 weeks, while VFR and tourists travelled for a median duration of 3 weeks. A significantly higher proportion of businessmen visited the Indian subcontinent (44; 15.3%, p < 0.0001) and was male (69; 57.0%, p = 0.0132). Africa was the preferred continent of tourists (508, 33.1%), while VFR mainly travelled to Latin America (38; 42.2%) and Asia (22; 24.4%). A minority visited the tropics or subtropics for the first time (208, 7.5%), among whom 92 (44.2%) rated themselves as intermediate to very susceptible to diarrhoea, compared to 940 (36.7%) among experienced travellers. Post-travel questionnaires were returned within a median of 10 days (interquartile range 2-30) after returning home.

Figure 1.

Overview of prospective participants recruitment. 1) functional gastrointestinal disease. 2) Informed consent

Table 1.

Demographic and selected behavioural factors of the travellers' cohort.

| Total | subgroups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD n = 962 |

mild diarrhoea n = 303 |

no diarrhoea abroad n = 1535 |

Classic TD n = 785 |

||

| Sex | n = 2800 | ||||

| Female | 1406 (50.2) | 466 (33.1) | 151 (10.7) | 789 (56.1) | 400 (28.4) |

| Male | 1394 (49.8) | 496 (35.6) | 152 (10.9) | 746 (53.5) | 385 (27.6) |

| Age group, years 1) | n = 2672 | ||||

| 18-30 | 829 (31.0) | 338 (40.8) | 93 (11.2) | 389 (46.9) | 292 (35.2) |

| 31-40 | 882 (33.0) | 283 (32.1) | 102 (11.6) | 497 (56.3) | 230 (26.1) |

| 41-60 | 734 (27.5) | 242 (33.0) | 76 (10.4) | 416 (56.7) | 186 (25.3) |

| >60 | 227 (8.5) | 55 (24.2) | 18 (7.9) | 154 (67.8) | 40 (17.6) |

| Origin (first 5 years of life) | n = 2764 | ||||

| European | 2616 (94.6) | 899 (34.4) | 287 (11.0) | 1430 (54.7) | 734 (28.0) |

| TD high risk country2) | 75 (2.7) | 25 (33.3) | 6 (8.0) | 44 (58.7) | 19 (25.3) |

| other | 73 (2.6) | 24 (32.9) | 8 (10.9) | 41 (56.2) | 19 (26.0) |

| Education | n = 2745 | ||||

| Vocational school level 1 3) | 588 (21.4) | 196 (33.3) | 71 (12.1) | 324 (55.1) | 151 (25.7) |

| Vocational school level 2 4) | 754 (27.5) | 258 (34.2) | 75 (9.9) | 421 (55.8) | 212 (28.1) |

| University | 1403 (51.1) | 504 (35.9) | 152 (10.8) | 758 (54.0) | 407 (29.0) |

| Destination5) | n = 2790 | ||||

| Africa | 903 (32.4) | 313 (34.7) | 107 (11.8) | 483 (53.5) | 246 (27.2) |

| Asia | 1266 (45.4) | 407 (32.1) | 126 (10.0) | 733 (57.9) | 335 (26.5) |

| Latin America | 617 (22.1) | 234 (37.9) | 70 (11.3) | 313 (50.7) | 202 (32.7) |

| Travel type | n = 1750 | ||||

| Tourism | 1539 (87.9) | 545 (35.4) | 173 (11.2) | 821 (53.3) | 444 (28.8) |

| Family/VFR | 90 (5.1) | 42 (46.6) | 15 (16.6) | 33 (36.7) | 36 (40.0) |

| Business | 121 (10.8) | 37 (30.6) | 10 (8.3) | 74 (61.2) | 27 (22.3) |

| Travel duration, weeks 1) | n = 2800 | ||||

| mean ± sd | 3.2 ± 1.6 | 3.6 ± 1.9 | 3.2 ± 1.6 | 3.0 ± 1.4 | 3.7 ± 1.9 |

| median (range) | 3 (1-8) | 3 (1-8) | 3 (1-8) | 3 (1-8) | 3 (1-8) |

| 1-3 weeks | 1849 (66.0) | 560 (30.3) | 206 (11.1) | 1083 (58.6) | 447 (24.2) |

| 3.5 -5 weeks | 674 (24.1) | 249 (36.9) | 74 (11.0) | 351 (52.1) | 205 (82.3) |

| 5.5-8 weeks | 277 (9.9) | 153 (55.2) | 23 (8.3) | 101 (36.5) | 133 (48.0) |

| History of travel | n = 2768 | ||||

| Experienced | 2560 (92.5) | 867 (33.9) | 275 (10.7) | 1418 (55.4) | 706 (27.6) |

| Newcomer (first such journey) | 208 (7.5) | 84 (40.4) | 24 (11.5) | 100 (48.1) | 70 (33.6) |

| Smoking habits | |||||

| n = 2788 | |||||

| previous smoker | 1041 (37.3) | 369 (35.4) | 100 (9.6) | 572 (54.9) | 299 (28.7) |

| previous non-smoker | 1747 (62.7) | 590 (33.7) | 201 (11.5) | 956 (54.7) | 483 (27.6) |

| n = 2793 | |||||

| smoker | 872 (31.2) | 314 (36.0) | 81 (9.3) | 477 (54.7) | 263 (30.2) |

| non-smoker | 1921 (68.8) | 644 (33.5) | 221 (11.5) | 477 (24.8) | 519 (27.0) |

| Daily alcohol consumption | n = 2790 | ||||

| yes | 594 (21.3) | 200 (33.7) | 70 (11.8) | 324 (54.5) | 161 (27.1) |

| >1 glass daily | 90 (15.4) | 32 (35.6) | 10 (11.1) | 48 (53.3) | 24 (26.7) |

| no | 2196 (78.7) | 757 (34.5) | 231 (10.5) | 324 (14.7) | 620 (28.2) |

NOTE. TD is travellers' diarrhoea, three or more unformed stools with or without additional symptom, classic TD with at least one accompanying symptom, mild diarrhoea one or two unformed stools per 24 hours. VFR is visiting friends and relatives.

1) Significant. Chi square test, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. TD patients were compared to those with no diarrhoea abroad. All other factors not significant.

2) Defined by Steffen et al. [2,4]

3) Swiss obligatory school to apprenticeship school

4) Swiss Matura (baccalaureat, general qualification for university access) and federal diplomas

5) Oceania was omitted as only 4 travellers had visited this region

Figure 2.

First two-week-incidences in selected areas. (N = 2794). CTD classic TD (n = 523). ATD all TD (n = 710). DYS dysentery (n = 166)

Among other diseases (596; 25.8%), common cold (277, 9.9%) and headache (106; 3.8%) were most reported. Fever independent from TD was mentioned by 45 (2.5%) study participants.

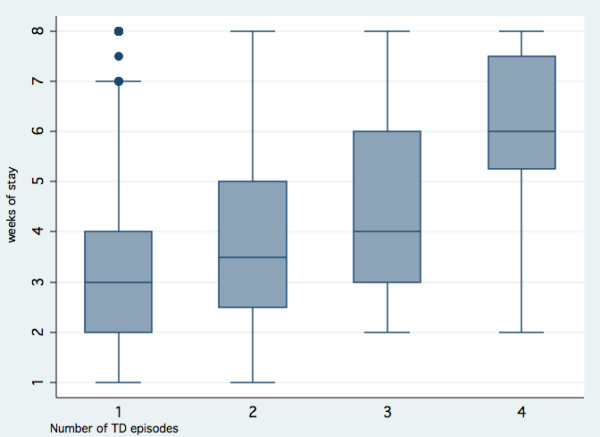

Travellers' diarrhoea

Among the 2800 exposed, 962 had TD, resulting in a TD attack rate of 34.4% (95% CI 32.6-36.1) and in a worldwide TD incidence for the first two-weeks stay of 26.2% (95% CI 24.5-27.8). A majority of 573 volunteers (69.8%) reported a single TD episode, 248 (30.2%) suffered from more than one episode while abroad. The number of TD episodes experienced increased approximately linearly with the duration of stay as illustrated in figure 3. A total of 785 suffered classic TD while abroad (28.0%; 95%CI 26.4-29.7) with a classic TD 2-weeks incidence of 19.9 (18.3-21.4 95%CI). A total of 303 (10.8%) experienced mild diarrhoea. The most frequent accompanying symptoms were tenesmus (56.0% among the TD patients) and cramps (49.2%). Fever (mean 38.4 ± 0.8°C) or vomiting was reported by approximately 15% (146 with fever, 136 vomiting), and 166 (17.3%) study subjects suffered from dysentery. The highest 2 weeks incidence rates for dysentery were recorded in Central and in Western Africa, and on the Indian subcontinent (figure 2). A total of 170 (17.7%) TD patients reported no accompanying symptom, but experienced a median of 4 stools per 24 hours (range 3-20).

Figure 3.

Number of TD episodes by weeks of stay within a high-risk region. (n = 821). High-risk TD regions as defined by Steffen et al. [2,4]. 1) 1 episode (n = 573). Median 3 (1-8), mean 3.4 ± 1.7 weeks. 2) 2 episodes (≥72 h-interval) (n = 189). Median 3.5 (1-8), mean 4.1 ± 2.0 weeks. 3) 3 episodes (≥72 h-interval) (n = 51). Median 4 (2-8), mean 4.4 ± 2.0 weeks. 4) 4 episodes (≥72 h-interval) (n = 8). Median 6 (2-8), mean 5.9 ± 2.0 weeks. Participants with missing episodes n = 141 (14.7%)

The number of TD episodes reported had no significant influence on the use of antibiotics or probiotics (p = 0.282, p = 0.532, respectively). In contrast TD patients who reported treatment with loperamide (co-medication with antibiotics excluded) had more TD episodes (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.05-2.19, p = 0.0026). TD occurred on average within 2.1 weeks after arrival (median 2 days) and patients counted on average 4 stools per day. One in every nine (111, 11.5%) experienced diarrhoea for longer than one week, with 37 (3.8%) individuals suffering from persistent (≥14 days of TD) and 11 (1.1%) from chronic diarrhoea (≥ 30 days). Roughly two thirds of patients (614, 63.8%) could pursue their planned activities, but 102 (10.8%) were confined to bed or consulted a physician, including 60 with dysentery (36.1% of all dysenteric patients).

Among treated patients, 343 (57.6%) chose an antimotility agent for self-medication of TD, 137 (23.0%) a probiotic and 51 combined both. A total of 116 (12.3%) TD patients reported intake of antibiotics, 65 of them (56.0%) for diarrhoea. The most frequently used antibiotics against TD were quinolones (e.g. ciprofloxacin), but trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were also reported (6 cases). The use of charcoal was reported by 70 persons (19.5%) and oral rehydration treatment was mentioned in 62 (6.4%) of the TD subjects and in 16 (9.6%) of dysenteric subjects. Among the dysentery cases, 35 (21.1%) were treated with an antibiotic, 79 (47.6%) used non-antibiotic medication exclusively, and this was most commonly loperamide (n = 38). Against advice, 152 (58.7%; p = 0.0191) travellers with an academic background reported consumption of tap water, and 60 (39.5%) of those developed TD. Health characteristics and some preventive attitudes are reported in table 2.

Table 2.

Health characteristics and TD-preventive attitudes abroad (N = 2800).

| Total1) | subgroups | p value2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD n = 962 |

mild diarrhoea n = 303 |

no diarrhoea abroad n = 1535 |

|||

| Body Mass Index | n = 2789 | 0.734 | |||

| <18.5 | 91 (3.3) | 32 (35.2) | 9 (9.9) | 50 (54.9) | |

| 18.5-29.9 | 2612 (93.7) | 892 (34.2) | 283 (10.8) | 1437 (55.0) | |

| ≥30.0 | 86 (3.0) | 34 (39.5) | 9 (10.5) | 43 (50.0) | |

| Allergy (MD assessed) 3) | n = 2785 | 0.721 | |||

| none | 1837 (66.0) | 627 (34.1) | 205 (11.2) | 1005 (54.7) | |

| any | 632 (34.0) | 224 (35.4) | 59 (9.3) | 349 (55.2) | |

| allergic asthma | 110 (17.5) | 50 (45.5) | 11 (10.0) | 49 (44.5) | |

| allergic asthma vs. others | 0.013 | ||||

| Comedication3) | n = 2800 | 0.741 | |||

| none | 2475 (88.4) | 853 (34.5) | 265 (10.7) | 1357 (54.8) | |

| any | 325 (11.6) | 109 (33.5) | 38 (11.7) | 178 (54.8) | |

| mental/behavioural 4) | 52 (16.8) | 25 (23.6) | 5 (9.6) | 22 (13.3) | |

| mental/behavioural vs. others | 0.031 | ||||

| History of diarrhoea | n = 1843 | n = 674 | n = 215 | n = 954 | 0.009 |

| none | 855 (46.4) | 282 (33.0) | 99 (11.6) | 474 (55.4) | |

| TD ever experienced | 955 (51.8) | 377 (39.5) | 110 (11.5) | 468 (49.0) | |

| Don't remember | 33 (1.8) | 15 (45.5) | 6 (18.2) | 12 (36.4) | |

| History of TD incapacitation | n = 1029 | n = 373 | n = 120 | n = 497 | 0.139 |

| low | 528 (51.3) | 197 (37.3) | 65 (12.3) | 266 (50.4) | |

| intermediate to severe | 501 (48.7) | 215 (42.9) | 55 (11.0) | 231 (46.1) | |

| Subjective diarrhoea susceptibility | n = 1656 | n = 584 | n = 186 | n = 886 | 0.001 |

| low | 617 (37.3) | 186 (30.1) | 54 (8.7) | 377 (61.1) | |

| intermediate | 974 (58.8) | 363 (37.3) | 125 (12.8) | 486 (49.9) | |

| high | 65 (3.9) | 35 (53.8) | 7 (10.7) | 23 (35.4) | |

| Diarrhoea episode <4 months before index travel5) | n = 2800 | <0.001 | |||

| 347 (12.4) | 172 (49.6) | 42 (13.9) | 133 (38.3) | ||

| Catering3) | n = 2323 | n = 792 | n = 252 | n = 1279 | |

| Buffet meals | 2190 (94.3) | 742 (33.9) | 234 (10.7) | 1214 (55.4) | 0.380 |

| Private/family meals | 982 (42.3) | 374 (38.1) | 91 (9.3) | 517 (52.6) | 0.001 |

| Street vendors meals | 882 (38.0) | 310 (35.1) | 98 (11.1) | 474 (53.7) | 0.389 |

| Adherence to "cook it, boil it, peel it or forget it" | n = 2318 | 0.299 | |||

| 1428 (61.6) | 477 (33.4) | 160 (11.2) | 791 (55.4) | ||

NOTE. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. NS, not significant. MD is medical doctor, TD travellers' diarrhoea.

1) Included mentioned subgroups and mild diarrhoea cases

2) chi square test. TD patients were compared to those with no diarrhoea abroad.

3) Multiple answers possible

4) Mainly antidepressive medication (n = 49)

5) Pre-existing FGID (Functional Gastrointestinal Disease) patients and subjects with diarrhoea unresolved or lasting ≥14 d within this diarrhoea episode <4 months before index travel were excluded as defined in the exclusion criteria

Factors influencing TD

Table 3 shows risk factors independently associated with TD with increasing age being the only protective one. We found no significant associations, either with other reported allergies (e.g. hay fever, atopic dermatitis), nor with other pre-travel co-medications (e.g. hormonal). Seasonality and gender were not associated to TD rates.

Table 3.

Odds ratios (OR) for the risk factors of developing TD.

| Variable | Univariate OR N = 2800 |

Multiple OR N = 2565 |

Final model OR N = 2565 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender1) | 0.90 (0.77-1.05) | 1.01 (0.80-1.28) | 0.96 (0.80-1.15) |

| Age (years)2) 3) | 0.98 (0.98-0.99) | 0.98 (0.97-1.00) | 0.98 (0.98-0.99) |

| Weeks of stay3) | 1.26 (1.20-1.33) | 1.27 (1.17-1.37) | 1.28 (1.21-1.35) |

| Visiting Friends and Relatives2) | 1.62 (1.06-2.48) | 1.41 (0.85-2.33) | |

| Smoking1) | 1.11 (0.94-1.32) | 1.06 (0.82-1.36) | |

| Daily alcohol drinking1) | 0.94 (0.79-1.17) | 1.01 (0.76-1.34) | |

| Allergic asthma1) | 1.62 (1.11-2.38) | 1.70 (0.95-3.07) | 1.67 (1.10-2.54) |

| Psychiatric co-medication1) | 1.79 (1.05-3.08) | 1.88 (0.94-3.75) | 2.11 (1.17-3.80) |

| Diarrhoea pre-travel1) | 2.07 (1.65-2.59) | 1.78 (1.31-2.43) | 2.03 (1.59-2.54) |

| TD independent fever1) 4) | 8.64 (4.01-17.85) | 5.72 (2.27-14.38) | 6.56 (3.06-14.04) |

| Malaria chemoprophylaxis1) | 1.19 (0.98-1.44) | 1.31 (1.00-1.72) | 1.38 (1.12-1.70) |

| Consuming tap water abroad1) | 1.08 (0.82-1.41) | 0.88 (0.62-1.25) | |

| Self-reported adherence to "cook it, boil it, peel it or forget it" 1) | 0.91 (0.76-1.09) | 1.00 (0.79-1.27) | |

| Body Mass Index3) | 1.01 (0.99-1.04) | 1.05 (1.01-1.09) | 1.04 (1.01-1.08) |

| Adverse life event pre-travel1) | 0.94 (0.72-1.22) | 0.98 (0.66-1.46) | |

| High stress level pre-travel1) | 1.11 (0.84-1.47) | 0.94 (0.62-1.42) |

NOTE. OR: Odds ratio

1) Reference group of variable: all others. For Gender Male. For Visiting Friends and Relatives Tourists and Business Travellers, for Smoking Non-smokers (previous smokers included), for Daily alcohol drinking No daily alcohol drinking reported, for Allergic asthma No allergic asthma reported, for Psychiatric co-medication No Psychiatric co-medication reported, for Diarrhoea pre-travel No diarrhoea pre-travel, for TD independent fever All others, for Malaria chemoprophylaxis No malaria chemoprophylaxis reported, for Consuming tap water abroad No such consuming reported, for Self-reported adherence to "cook it, boil it, peel it or forget it" Self-reported non-adherence, for Adverse life event No adverse life event reported pre-travel, for High stress level Very low to intermediate stress level pre-travel.

2) Some missing data which accounts for ~10% less of N in the Final model.

3) Continuous variables

4) Imputation of missing data for later inserted question using the pattern of gender, destination continent and education variables.

Discussion

In view of the fact that the TD incidence has been reduced in some countries such as Jamaica [16] and Thailand [17], updated worldwide regional incidence data were long overdue. Overall, we observe a substantial decrease in the two weeks incidence rate, nowhere did we find rates exceeding 50 or even 60% as documented in a large study conducted a decade ago (3, 4). Most regions which were high risk remained in high risk destination group [2,3,8,18,19]. Particularly East Asia, including China, Southeast Asia and to a lesser degree Latin America, showed a marked decrease in classic TD risk. Known high-risk TD destinations such as the Middle East, North Africa and the Caribbean have been underrepresented in our study, since visitors to those destinations generally do not consider a pre-travel consultation as indicated [20]. Some of these areas however, recently experienced a similar decrease in fecal-orally transmitted diseases[21]. For TD we confirmed younger age and longer travel duration as risk factors. In contrast, neither smoking nor consuming alcohol nor gender significantly influenced the occurrence of TD. TD patients, who had previously experienced TD, reported a significantly higher susceptibility to diarrhoea (p = 0.0127); that may be associated with genetic factors [22,23].

Allergic asthma, mental/behavioural co-medication, a high BMI, and a TD-independent fever episode to our knowledge have so far never been considered risk factors for TD. Such findings, however, may be clinically relevant and enhanced preventive measures to protect travellers vulnerable to multiple health impairments abroad should be considered. Allergic asthma as a risk factor needs further exploration [24,25], however both, atopic dermatitis and hay fever did not influence TD in our cohort. Within psychiatric co-medication antidepressants might be associated with diarrhoea as a side effect [26,27]. An elevated BMI resulted in a marginally increased risk ratio, similarly to being a predisposing factor for community-based diarrhoea [28-30]. Obese people have a higher food intake, and may thus consume a larger inoculum of pathogens. Lastly, a fever episode independent of TD was suggestive of some low-grade inflammatory and/or immunological processes [31,32]. Our questionnaire did not allow to assess the chronology of TD independent fever.

Loperamide was widely used to treat TD in our cohort, which is consistent with other reports [10,33] and some of the guidelines [34,35]. Only a minority of 6.8% of all cases relied on an antibiotic therapy for TD, which in most cases was carried in their travel medical kit. Almost 10% turned to a local pharmacy, potentially exposing themselves to the risk of fake medication abroad or receiving medication stored at inadequately temperatures [36,37].

Our study design with inherent selection bias [38] and missing chronology of TD treatment did not allow evaluation of the various treatment schedules. However, patients without antibiotic TD treatment (most using loperamide) were found to have significantly more TD episodes; targeted studies are needed to determine whether loperamide is associated with recurrent TD episodes.

Half of our study population had a university degree, travelling mostly as tourists but also for business. They might spend more money on travelling and be more likely to ask for pre-travel health advice. Hence, our results, although not ideal with respect to behaviour, may reflect a rather high socio-economic stratum. As our study participants all obtained the usual advice on hygiene measures to prevent TD, and as many were non compliant these approaches need to be improved, or other means of prophylaxis offered. For instance, an alternative approach may be to increase the public and tourism industry demand for food safety to reduce the burden of TD among travellers [39]. Previous studies often questioned travellers at the airport before or during the flight home, this one, however, some days after return. Thus, this latter study would also include TD which occurred in those first days back home, and one would expect slightly higher rates as compared to the older studies.

Conclusion

This study shows that diarrhoea remains a very frequent health problem in travellers, although there is a trend to reduced incidence rates in various parts of the world. Besides well-known risk factors like duration of stay, young adult age, etc., also a patients' history of allergic asthma, of pre-travel diarrhoea and of TD-independent fever will need further investigation.

Competing interests

RS has accepted fees or reimbursement for actively participating in education, consulting, advisory boards, research and also for attending meetings from Crucell, DrFalk Pharma, Intercell, Novartis, Salix Pharmaceuticals, and Santarus. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

Authors' contributions

MM and RS were involved in the study design and supervision. RP and MM were involved in data collection. RP, MM and RS were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data. AT provided statistical expertise. All authors drafted the article and were responsible for critical revision for intellectual content. All authors gave final approval to the manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Raffaela Pitzurra, Email: pitzurra@ifspm.uzh.ch.

Robert Steffen, Email: roste@ifspm.uzh.ch.

Alois Tschopp, Email: alois.tschopp@ifspm.uzh.ch.

Margot Mutsch, Email: muetsch@ifspm.uzh.ch.

References

- Kean BH, Waters S. The diarrhea of travelers. I. Incidence in travelers returning to the United States from Mexico. AMA Arch Ind Health. 1958;18(2):148–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen R. Epidemiology of traveler's diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(Suppl 8):S536–540. doi: 10.1086/432948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Sonnenburg F, Tornieporth N, Waiyaki P, Lowe B, Peruski LF Jr, DuPont HL, Mathewson JJ, Steffen R. Risk and aetiology of diarrhoea at various tourist destinations. Lancet. 2000;356(9224):133–134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02451-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen R, Tornieporth N, Clemens SA, Chatterjee S, Cavalcanti AM, Collard F, De Clercq N, DuPont HL, von Sonnenburg F. Epidemiology of travelers' diarrhea: details of a global survey. J Travel Med. 2004;11(4):231–237. doi: 10.2310/7060.2004.19007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WG, Irvine EJ, Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Rance L. Functional gastrointestinal disorders in Canada: first population-based survey using Rome II criteria with suggestions for improving the questionnaire. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47(1):225–235. doi: 10.1023/A:1013208713670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA. Rome III: the new criteria. Chin J Dig Dis. 2006;7(4):181–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2006.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen R, Collard F, Tornieporth N, Campbell-Forrester S, Ashley D, Thompson S, Mathewson JJ, Maes E, Stephenson B, DuPont HL. Epidemiology, etiology, and impact of traveler's diarrhea in Jamaica. Jama. 1999;281(9):811–817. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.9.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passaro DJ, Parsonnet J. Advances in the prevention and management of traveler's diarrhea. Curr Clin Top Infect Dis. 1998;18:217–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diarrhoeal disease. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs330/en/index.html

- Hill DR. Occurrence and self-treatment of diarrhea in a large cohort of Americans traveling to developing countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62(5):585–589. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Migrant Stock: The 2005 Revision Population Database. Definition of major areas and regions. http://esa.un.org/migration/index.asp?panel=3

- International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Current version ICD-10. http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/

- Kozicki M, Steffen R, Schar M. 'Boil it, cook it, peel it or forget it': does this rule prevent travellers' diarrhoea? Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14(1):169–172. doi: 10.1093/ije/14.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlim DR. Looking for evidence that personal hygiene precautions prevent traveler's diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(Suppl 8):S531–535. doi: 10.1086/432947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcombe RG, Altman DG. In: Statistics with confidence. 2. Altman DG, editor. BMJ Books; 2000. Proportions and their differences; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley DV, Walters C, Dockery-Brown C, McNab A, Ashley DE. Interventions to prevent and control food-borne diseases associated with a reduction in traveler's diarrhea in tourists to Jamaica. J Travel Med. 2004;11(6):364–367. doi: 10.2310/7060.2004.19205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chongsuvivatwong V, Chariyalertsak S, McNeil E, Aiyarak S, Hutamai S, Dupont HL, Jiang ZD, Kalambaheti T, Tonyong W, Thitiphuree S. Epidemiology of travelers' diarrhea in Thailand. J Travel Med. 2009;16(3):179–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst F, Steffen R. Update on the Epidemiology of Traveler's Diarrhea in East Africa. J Travel Med. 1997;4(3):118–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.1997.tb00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbach SL, Kean BH, Evans DG, Evans DJ Jr, Bessudo D. Travelers' diarrhea and toxigenic Escherichia coli. N Engl J Med. 1975;292(18):933–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197505012921801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leder K, Tong S, Weld L, Kain KC, Wilder-Smith A, von Sonnenburg F, Black J, Brown GV, Torresi J. Illness in travelers visiting friends and relatives: a review of the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(9):1185–1193. doi: 10.1086/507893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baaten G, Sonder JM, van der Loeff M, Coutinho R, van den Hoek A. Fecal-Orally Transmitted Diseases Among Travelers Are Decreasing Due to Better Hygienic Standards at Travel Destination. J Travel Med. 2010. in press . [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mohamed JA, DuPont HL, Jiang ZD, Belkind-Gerson J, Figueroa JF, Armitige LY, Tsai A, Nair P, Martinez-Sandoval FJ, Guo DC. A novel single-nucleotide polymorphism in the lactoferrin gene is associated with susceptibility to diarrhea in North American travelers to Mexico. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(7):945–952. doi: 10.1086/512199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang ZD, Okhuysen PC, Guo DC, He R, King TM, DuPont HL, Milewicz DM. Genetic susceptibility to enteroaggregative Escherichia coli diarrhea: polymorphism in the interleukin-8 promotor region. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(4):506–511. doi: 10.1086/377102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matricardi PM, Rosmini F, Panetta V, Ferrigno L, Bonini S. Hay fever and asthma in relation to markers of infection in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(3):381–387. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.126658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matricardi PM, Rosmini F, Riondino S, Fortini M, Ferrigno L, Rapicetta M, Bonini S. Exposure to foodborne and orofecal microbes versus airborne viruses in relation to atopy and allergic asthma: epidemiological study. BMJ. 2000;320(7232):412–417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7232.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uher R, Farmer A, Henigsberg N, Rietschel M, Mors O, Maier W, Kozel D, Hauser J, Souery D, Placentino A. Adverse reactions to antidepressants. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(3):202–210. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.061960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla P, Cipriani A, Hotopf M, Barbui C. Side-effect profile of fluoxetine in comparison with other SSRIs, tricyclic and newer antidepressants: a meta-analysis of clinical trial data. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2005;38(2):69–77. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moayyedi P. The epidemiology of obesity and gastrointestinal and other diseases: an overview. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(9):2293–2299. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0410-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley NJ, Howell S, Poulton R. Obesity and chronic gastrointestinal tract symptoms in young adults: a birth cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(9):1807–1814. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Aros S, Locke GR, Camilleri M, Talley NJ, Fett S, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Obesity is associated with increased risk of gastrointestinal symptoms: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(9):1801–1806. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller R, Garsed K. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(6):1979–1988. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell N, Huntley B, Beech T, Knight W, Knight H, Corrigan CJ. Increased prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with allergic disease. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(977):182–186. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.049585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen R, van der Linde F, Gyr K, Schar M. Epidemiology of diarrhea in travelers. Jama. 1983;249(9):1176–1180. doi: 10.1001/jama.249.9.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS). Statement on travellers' diarrhea. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2001;27:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPont HL, Ericsson CD, Farthing MJ, Gorbach S, Pickering LK, Rombo L, Steffen R, Weinke T. Expert review of the evidence base for self-therapy of travelers' diarrhea. J Travel Med. 2009;16(3):161–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolf PM, Bernstein IB. Counterfeit drugs. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(14):1384–1386. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelesidis T, Kelesidis I, Rafailidis PI, Falagas ME. Counterfeit or substandard antimicrobial drugs: a review of the scientific evidence. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60(2):214–236. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Bias and causal associations in observational research. Lancet. 2002;359(9302):248–252. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdussalam M, Kaferstein FK. Food safety in primary health care. World Health Forum. 1994;15(4):393–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]