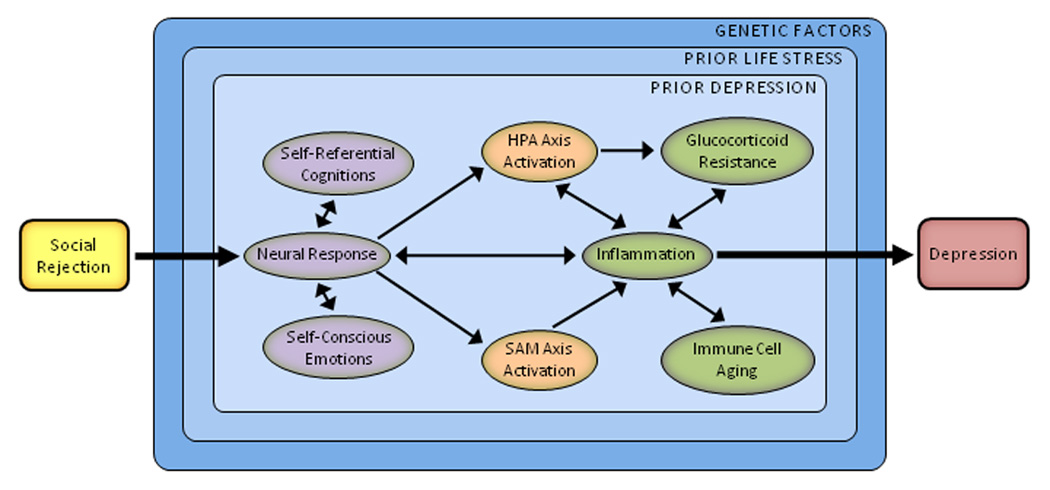

Fig. 1.

A psychobiological model of social rejection and depression. Stressors involving social rejection include elements of social-evaluative threat, social demotion, and social exclusion. Because of these attributes, rejection-related stressors elicit a distinct and integrated set of cognitive, emotional, and biological changes that promote behavioral disengagement and withdrawal. The process begins with the perception of threat. Social rejection events activate brain regions involved in processing negative affect and rejection-related distress (e.g., anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex). They also elicit negative self-referential cognitions (e.g., “I’m undesirable,” “I’m unlovable,” and “Other people don’t like me”) and related self-conscious emotions (e.g., shame, humiliation). Downstream biological consequences include upregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) axis, and inflammatory response. Resulting increases in inflammation may be indexed by the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α. These cytokines are important because they induce a constellation of depressotypic behaviors called sickness behaviors. Although these changes can be short-lived, sustained inflammation may occur via several pathways, including glucocorticoid resistance, catecholamines, sympathetic innervation of immune organs, and immune cell aging. This response also may be moderated by several factors, including prior life stress, prior depression, and genes implicated in stress reactivity.