FIG. 10.

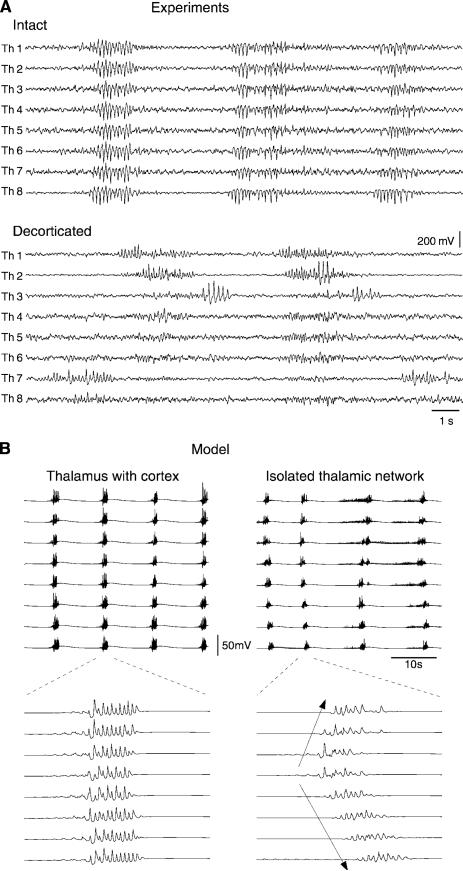

The large-scale synchrony of spindle oscillations depends on corticothalamic feedback. A: removal of the cerebral cortex affects the pattern of spindle oscillations in the thalamus. Field potentials were recorded using 8 tungsten electrodes equidistant of 1 mm (Th1–Th6) inserted in the cat thalamus under barbiturate anesthesia in the intact brain (Intact) and after removal of the cortex (Decorticated). After decortication, recordings from approximately the same thalamic location showed that spindling continued at each electrode site, but their coincidence in time was lost. The 8-electrode configuration was positioned at different depths within the thalamus (from −2 to −6) and different lateral planes (from 2 to 5); all positions gave the same result. [Modified from Contreras et al. (60).] B: computational model of large-scale coherence in the thalamocortical system. Spontaneous spindles are shown in the presence of the cortex (left panels) and in an isolated thalamic network (right panels) under the same conditions. The traces indicate local averages computed from 21 adjacent TC cells sampled from 8 equally spaced sites on the network. Bottom graphs represent averages of a representative spindle at 10 times higher temporal resolution. The near-simultaneity of oscillations in the presence of the cortex is qualitatively different from the propagating patterns of activity in the isolated thalamic network (arrows). [Modified from Destexhe et al. (100).]