Abstract

This study assessed the acceptability and preference for sexual barrier and lubricant products among men in Zambia following trial and long-term use. It also examined the role of men's preferences as facilitators or impediments to product use for HIV transmission reduction within the Zambian context. HIV-seropositive and - serodiscordant couples were recruited from HIV voluntary counseling and testing centers in Lusaka between 2003 and 2006; 66% of those approached agreed to participate. HIV seropositive male participants participated in a product exposure group intervention (n = 155). Participants were provided with male and female condoms and vaginal lubricants (Astroglide® [BioFilm, Inc., Vista, CA] & KY® gels [Johnson & Johnson, Langhorne, PA], Lubrin® suppositories [Kendwood Therapuetics, Fairfield, NJ]) over three sessions; assessments were conducted at baseline, monthly over 6 months and at 12 months. At baseline, the majority of men reported no previous exposure to lubricant products or female condoms and high (79%) levels of consistent male condom use in the last 7 days. Female condom use increased during the intervention, and male condom use increased at 6 months and was maintained over 12 months. The basis for decisions regarding lubricant use following product exposure was most influenced by a preference for communicating with partners; participant preference for lubricant products was distributed between all three products. Results illustrate the importance of development of a variety of products for prevention of HIV transmission and of inclusion of male partners in interventions to increase sexual barrier product use to facilitate barrier acceptability and use in Zambia.

Introduction

Globally the total number of persons living with HIV was estimated to be 33.2 million in November 2007, of whom over 22.5 million reside in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Zambia, a sub-Saharan country of 10.2 million persons, has urban prevalence rates of 23% (1.1 million estimated infections nationwide).2

Slowing rates of new infections suggest that HIV prevention may be most achievable through a combination of behavioral and biomedical interventions3 that integrate antiretroviral therapy (ART)4, 5 and prevention programs. Prevention programs such as voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) that target the sexual relationships most frequently associated with HIV transmission, marital and cohabiting couples,6, 7 have proven successful in reducing transmission among serodiscordant couples8, 9 but improved counseling protocols are still needed.10 A seropositive diagnosis and HIV counseling may increase condom use only temporarily11, 12 and couple members may not protect the uninfected partner13, 14 or restrict transmission of potentially resistant virus between infected partners13, 14 or even disclose their serostatus16 because of fear of violence in response.

Although male condoms have high efficacy (93%–95%)17 in the reduction of transmission of HIV and other STDs, their impact on disease prevention has been reduced by low acceptability and inconsistent use.18–20 Within sexual relationships, men are the primary sexual decision-makers20 and are in a position of dominance over their female counterparts who may not be able to use strategies for protection consistently.19 In fact, condom use appears to occur primarily outside marital relationships in the context of extramarital relationships.21 Women are limited in their ability to negotiate use of male condoms21,22 and the level of female condom use23,24 and acceptability is even lower than that of male condoms.

Limited male and female condom use emphasizes the need for alternative methods, such as vaginal chemical barriers, e.g., microbicides,3 for protection from disease transmission. However, acceptability-related limitations may reduce the uptake of microbicides as a result of product characteristics, e.g., viscosity, delivery system, timing.15, 18,25–30 Current microbicide vehicles offered in a vaginal lubricant format may also have limited acceptability due to the specific features of lubricants, e.g., wetness, odor, taste, appearance. Thus, assessment of the acceptability of vaginal lubricants may provide information regarding the eventual acceptability of microbicides in similar formats.

Influencing sexual product use requires both sexual partners to make significant changes in their sexual practices.31 Our previous research in the US and Zambia found group interventions to enhance acceptability and use of sexual barrier products among HIV-seropositive and -negative women18–20, 30 and men.22 This study assessed the acceptability and preference for sexual barrier and lubricant products among men in Zambia following a group intervention utilizing trial and long-term use. It also examined the role of men's preferences as facilitators or impediments to product use for HIV transmission reduction within the Zambian context.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The Partner Project recruited 440 HIV-positive seroconcordant and discordant Zambian couples 18 years of age or older between January 2003 and June 2006. The following analyses were conducted utilizing data from the sample of seropositive male participants randomized to the intervention condition (n = 155). Because of the ethical concerns related to the transmission of HIV by participants, no control group or “usual care” arm was included in this study. Data from our previous studies indicate that even enhanced “usual care” VCT clients significantly decreased their use of sexual barrier products over time.22

Participant intervention and examination protocol

Prior to participant recruitment, Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee approvals were obtained in accordance with the provisions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the University of Zambia regarding the conduct of research.

Study candidates currently in heterosexual couple relationships were recruited from VCT clinics in the University Teaching Hospital, community health centers and nongovernmental organizations. Couples were enrolled following HIV counseling and testing and provided verification of seropositive status of one or both members of the couple. Couples were screened for eligibility, i.e., currently sexually active, 18 years or more, couple relationship, one member HIV seropositive; the primary reason for participant ineligibility was lack of current sexual activity. Participants then completed an informed consent to enroll, were tested for other sexually transmitted infections (STDs; syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea) and penile/vaginal infections, completed a baseline assessment and were then randomized to condition (Fig. 1). Participants were notified of their STD or screening results and provided with appropriate treatment prior to receiving study products.

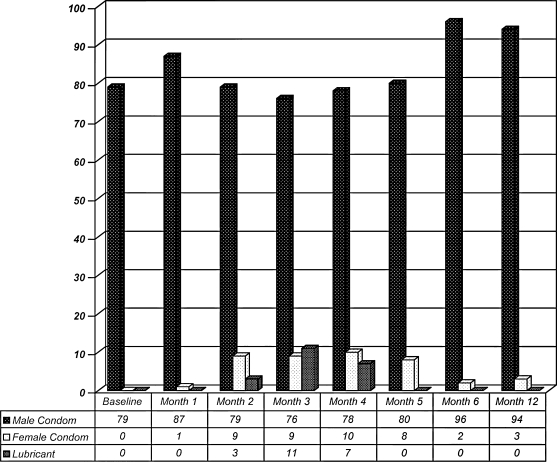

FIG. 1.

Percentage of sex acts with product by session.

Recruiters, assessors, and interventionists were multilingual and communicated in participant's dialect/language (e.g., Bemba, Nyanja, English). Assessments were conducted in the preferred language of the participant; the majority was conducted in English. Intervention sessions were conducted using a combination of Bemba, Nyanja and English, due to the mixture of audience language (73 local and 3 primary regional languages in Zambia). All participants received monetary compensation for their travel expenses. For those participants who were lost to follow-up, recruiters conducted home visits in the community to establish the reason for attrition. In the event of permanent loss of one member of a couple (e.g., illness, death, estrangement), individual participants were encouraged to continue to participate. The primary causes for attrition were employment, moving to another location, illness, and death.

Men and women randomized to the intervention participated in a product exposure group intervention (n = 155) and were provided with male and female condoms and vaginal lubricants (Astroglide® [BioFilm, Inc., Vista, CA] and KY® gels [Johnson & Johnson, Langhorne, PA], Lubrin® suppositories [Kenwood Therapuetics, Fairfield, NJ]) over 3 sessions.

Intervention

The intervention (n = 10 participants per group) was developed from feedback from pilot studies with men in the United States and Zambia, and has been described in earlier literature.20 The 2-hour sessions emphasized participation and experimentation with sexual barrier products and provided an opportunity for practice, feedback, and reinforcement of sexual risk reduction strategies. Participants engaged in skill building in a supportive environment utilizing communication techniques, negotiation skills, and experiential/interactive skill training to expand and reframe perceptions of barrier use and to increase self-efficacy and skill mastery. Material was presented utilizing the conceptual model of the theory of reasoned action and planned behavior,26 which suggests that perceived behavioral control influences intentions and behavior as predictors of sexual barrier use, and that personal intentions influence attitudes and subjective norms, which in turn influence beliefs about behavior. Facilitators were multilingual gender-matched male and female registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and health care staff trained in the administration of each condition. The intervention and accompanying videos were developed in English and translated into Zambian local languages (Nyanja and Bemba).

Session 1

The first session provided all participants with information on HIV/STD transmission, hierarchical counseling, and skill training to facilitate male and female condom use. Sessions included videos and written materials on instructions for use. The correct method of male and female condom use and commonly asked questions were presented and discussed. After each session, participants were provided with a 1-month supply of male and female condoms (9 male condoms and 3 female condoms each for man and woman, totaling 24 potential sex acts in 30 days), based on average sex act reporting of 3 times per week in previous samples in this context. Male condoms are available at no cost in community clinics; female condoms cost approximately $0.75 each. A lubricant pack was included with each female condom with in-session instructions provided for lubricant use with the female condom.

Session 2

The second session provided exposure and experiential training with vaginal lubricants (high- [Astroglide®] and low-viscosity [KY®] gels and suppositories [Lubrin®]) and supplies of male and female condoms and vaginal lubricants. Participants were strongly encouraged to use provided condoms with the vaginal lubricants during each act of sexual intercourse.

Session 3

The third session provided an opportunity for feedback and discussion regarding experiences with lubricants and condoms. Participants were provided additional condoms and lubricants of their choice.

Assessments

Demographic questionnaire

This questionnaire included data collection on age, religion, nationality, ethnicity, educational level, employment status, residential status, HIV serostatus (date of HIV infection [if known], mode of infection with HIV), marital status/current partner status, living situation, number of children and serostatus.

Sexual diary

This scale assessed the number of sex acts and the use of each sexual product during the reported sex act over the last 7 days in a “yes” or “no” format. The sexual diary was administered at baseline, 6 and 12 months, and monthly months 1 to 6.

Acceptability measures

These 25-item scales were developed using feedback from participants during pilot testing in the United States and Zambia and assessed most preferred product, perceived ease of use, comfort, fun, sexual pleasure, control, communication, confidence, and secrecy. The scales include rating and comparison between products using Likert-like scales of 1–7, personal and partner acceptability, personal and partner reactions to products, and ranking of attributes as most to least important. Analyses used Likert scale items associated with liking, ease of use, pleasure, in which higher scores were positive attitudes (higher scores on a scale of 1–7), and male perceptions of their own and their female partners' attitudes to products, in which lower scores indicate positive attitudes (scale 1–7). The acceptability measures were administered monthly, months 2 to 4.

Lubricant dosage

Vaginal lubricants were provided in two formats, full dose and chosen dose. Participants were asked to use the products at their full dosage (5 mL) initially, and to select their most preferred product and the amount of their most preferred dose at follow-up (2.5–5 mL). Reports were made using a Likert scale of 1–7 and data was collected at months 2 and 3.

Statistical analyses

This study reports correlations as Pearson's r statistics; all analyses used an α (2-tailed) of 0.05. Repeated measures between conditions were not conducted due to differences in sexual product use at baseline. Multiple regressions were used to assess the predictive power of acceptability variables and assess the relative contribution of each variable; analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used in significance testing for regressions. Data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Participants (n = 155) were HIV seropositive, sexually active, and living in urban Lusaka. Ages ranged from 21–62, the mean age of our participants was 37; 50% were unemployed, 27% worked part time. Ethnic groups included Bemba (27%), Nsenga, Ngoni, Tumbuka (26%), Tonga (14%), Lozi (15%), Mambwe, Namwanga (8%), and other ethnic groups (10%). The average level of educational attainment was completion of the sixth grade, ranging from primary school education (32%) to secondary education (65%). Most were married (99%) with children (93%; mean number of children = 3). Thirty-four percent of participants planned to have more children.

Baseline sexual behavior

At baseline, the reported percentage of consistent male condom use was high (79%), although 13% reported they had never used condoms. The majority of men had been sexually active in the last month (66%). Men with seronegative partners (15%) were not significantly more likely to use sexual barrier products (t = −0.33, p = 0.46); 1% were unaware of their partners' status. Contrary to expectations of higher levels of the practice, only 3% of participants reported being aware of their partners' use of products to make sex drier, less than 1% reported oral or anal sex. One percent of men thought their partners had additional sexual partners outside their primary relationship. No one reported previous exposure to lubricants or use of female condoms.

At 6 months postbaseline, sexually active participants reported 96% male condom use and 2% female condom use during sex acts in the last 7 days. No participants reported awareness of the use of dry sex practices. At 12 months, sexually active participants reported 94% male condom use and 3% female condom use during sex acts in the last 7 days. All product use from months 2–5, the months during which products were supplied, is presented in Figure 1.

Acceptabilty of male and female condoms and use—2 months

“Liking” female condoms (r = 0.406, p < 0.001) was associated with their use. Higher levels of female condom use were negatively associated with perceived “comfort” (r = −0.46, p < 0.001) and “ease” (r = −0.21, p = 0.04) in the use of male condoms. Comparatively, male condom use was associated with a preference for “being in control” (r = 0.20, p = 0.04), and sex with female condoms was negatively associated with male condom use (r = −0.36, p < 0.001). Male condoms were preferred over female condoms (male condom, mean 1.2; female condom, mean 3.3, on a 7-point Likert scale in which a score of 1 was most acceptable).

Hierarchical multiple regression was used to assess the ability of acceptability of comfort and ease of use to predict female condom use. Comfort of use was entered first, explaining 21% of the variance in use. After entry of ease of use, which did not contribute a significant portion of the variance (F change = 0.99, p = 0.32), the total variance explained by the model as a whole was 22%, F (2, 96) = 13.43, p < 0.001.

Acceptability of lubricants and use—3 and 4 months

After trial use, product ratings were based on the percentage of participants ranking a product as most preferred. The percentage of participants preferring products were evenly distributed after 2 and 3 months of use, respectively, as 37% and 32%, Lubrin® suppositories, 37% and 33%, KY® low-viscosity gel, and 26% and 24%, Astroglide® high-viscosity gel as most preferred delivery systems. Reported perceptions of lubricant products as “slippery,” “wet,” “messy,” or “runny” during the initial lubricant intervention session (2) prior to use was consistently associated with low levels of lubricant use (r = −0.28, p = 0.004). “Liking” using lubricants (r = −0.21, p = 0.027), describing them as “fun to use” (r = −0.20, p = 0.029) and a perception of “being in control” (r = 0.23, p = 0.01) and their use to “help to talk about sex” (r = 0.25, p = 0.008) and “not be kept secret” (r = 0.27, p = 0.004) were associated with lubricant use.

Hierarchical multiple regression was used to assess the ability of liking lubricants, fun, being in control, talking about sex and lubricants not being secret to predict lubricant use. Talking about sex was entered first, explaining 10% of the variance in use. After entry of lubricants not being kept secret, the total variance explained was 14%, F (2, 111) = 8.82, p < 0.001, and after entry of liking lubricants, the total variance explained by the model as a whole was 17%, F (3, 110) = 7.69, p < 0.001. Being in control and fun did not account for a significant proportion of the variance.

Product preference

After 2 months of trial use, product ratings based on product selection and stated preference indicated that participants preferences remained fairly evenly distributed between Lubrin® suppositories (32%), KY® low-viscosity gel (33%), and Astroglide® high-viscosity gel (24%) as the most preferred delivery systems.

Product characteristic importance

After 2 months of trial use, participants identified “ease of use,” “comfort,” and “increasing sexual pleasure” as being the most important factors in product preference; being “fun” to use and “being in control” were considered “least important” factors. Two thirds of those sampled reported that both they and their partners “liked” the lubricants.

Lubricant dosage

Vaginal lubricant chosen dose ranged from partial dose (2–3 mL) to full dose (5 mL). Participants were asked to use the products at their full dosage (5 mL) initially and to report their preferred dose at follow-up (2–3 to 5 mL). The modal distribution of responses indicated a preference for no greater than 0.5 of 5 mL.

Discussion

This intervention was designed to increase sexual barrier and lubricant product acceptability and use, and was found to be associated with increased male condom use over 12 months. While adding lubrication to sex is not a preferred practice among men in sub-Saharan Africa, this study suggests that men find lubricating products acceptable, and base their use on the perceived use of lubricants as an avenue to communicate about sex with their partners and preferences for not keeping product use secret. Results also suggest that men have specific preferences for delivery systems, emphasizing the importance of a variety of delivery systems and product characteristics to enhance acceptability in the Zambian context.

Overall response to the sexual barrier products and lubricants intervention was favorable. Our previous pilot research with HIV seropositive men and women in Zambia found that interventions increased barrier use26 and this finding appears to have been sustained. At baseline, men reported no previous exposure to vaginal lubricants and high levels of condom use. In contrast with previous studies assessing sexual behavior over shorter time periods, participants reported sustained increases in use of condoms up to 12 months postbaseline with no additional sexual behavior outside the primary relationship.35 Condom use was based on the perceived comfort of condoms.

Female condom use increased modestly during the course of the intervention, while they were distributed. Those reporting female condoms more acceptable were more likely to find male condoms less acceptable, implying that female condoms remain a potential adjunct to male condoms and may increase overall condom use, as noted in previous studies.35 Results suggest that typically low levels of female condom acceptability may be in part the result of their limited availability in Zambia, though male condoms remained more popular overall.

At baseline, participants' perceptions of lubricants as wet, runny, and messy were associated with consistent low levels of lubricant use, and at follow-up, preference for lower doses (e.g., 2–3 mL) of all lubricant products were preferred. There was no product that was most preferred among the gels or suppository; all product types were preferred by similar numbers of participants. Use of lubricants was most predicted by the perceived need for communication about sex that occurred as a result of its use, which suggests that interventions that encourage sexual communication may be useful in encouraging uptake of novel sexual barrier products.

In contrast with previous studies assessing sexual behavior over shorter time periods, participants reported sustained increases in use of sexual barrier products up to 12 months post-baseline. Anecdotal reports obtained during focus groups were strikingly different from those obtained during intervention groups during the study. Men displayed a remarkable shift in attitudes regarding preferences for dry sex over the use of lubricants. Initial focus group responses were primarily negative, but men given the opportunity to participate in the sexual barrier decision making process were responsive to the use of lubricants for protection from disease transmission.

Limitations of the study relate primary to the fact that lubricants have no actual value in the Zambian context; their use is in direct opposition to cultural preferences for drier sex. Thus, the use of lubricants during the study was limited and their use was not sustained as lubricants are also not available on the local economy. In addition, use of lubricants cannot be compared with the potential use of microbicides, which would have active HIV transmission prevention properties. Similarly, female condoms are no longer socially marketed in Zambia, and their use could not be sustained beyond the period during which they were supplied through the project visits. Finally, because of the differences between groups at baseline, no analysis over time between groups was possible. In addition, there was no control group in the intervention, and comparison of the level of male condom use among those in a control condition was not possible.

The role of Zambian men as the culturally defined decision-makers must be considered in programs to increase sexual barrier product acceptability and use. Sexual behavior occurs within a couple and as new strategies for HIV prevention are developed, research on acceptability and sexual barrier product use must address the preferences and behavior of both men and women within the context of both their sexual and cultural relationships.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the members of our research teams at the University Of Zambia School Of Medicine, the University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka, community sites providing referrals in Zambia and most importantly, our study participants.

This research was made possible by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, R24HD43613.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.UNAIDS (2007) UNAIDS/WHO AIDS Epidemic Update. 2007. http://data.unaids.org/pub/EPISlides/2007/2007_epiupdate_en.pdf. [Jan 28;2008 ]. http://data.unaids.org/pub/EPISlides/2007/2007_epiupdate_en.pdf

- 2.Central Statistical Office. ANC Sentinel Surveillance of HIV/Syphilis Trends in Zambia 1994–2002. Zambia: Central Statistical Office; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramjee G. Microbicides and other prevention technologies [Plenary presentation TUPL02}. Program and abstracts of the XVI International AIDS Conference; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Aug 13–18;2006 .2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bunnell R. Ekwaru JP. Solberg P, et al. Changes in sexual behavior and risk of HIV transmission after antiretroviral therapy and prevention interventions in rural Uganda [Abstract MOAC0204]. Program and abstracts of the XVI International AIDS Conference; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Aug 13–18;2006 ; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rapatski BL. Suppe F. Yorke JA. Reconciling different infectivity estimates for HIV-1. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:253–256. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243095.19405.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beyrer C. HIV epidemiology update and transmission factors: Risks and risk contexts [Plenary presentation MOPL02]. Program and abstracts of the XVI International AIDS Conference; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Aug 13–18;2006 . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hira SK. Feldblum PJ. Kamanga J. Mukelabai G. Weir SS. Thomas JC. Condom and nonoxynol-9 use and the incidence of HIV infection in serodiscordant couples in Zambia. Int J STD AIDS. 1997;8:243–250. doi: 10.1258/0956462971919994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth DL. Stewart KE. Clay OJ. van Der Straten A. Karita E. Allen S. Sexual practices of HIV discordant couples in Rwanda: Effects of a testing and counseling programme for men. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:181–188. doi: 10.1258/0956462011916992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKenna SL. Muyinda GK. Roth D. Rapid HIV testing and counseling for voluntary testing centers in Africa. AIDS. 1997;11:S103–S110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bunnell RE. Nassozi J. Marum E, et al. Living with discordance: Knowledge, challenges and prevention strategies of HIV-discordant couples in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2005;17:999–1012. doi: 10.1080/09540120500100718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen SA. Karita E. N'Gandu N. Tichacek A. The evolution of voluntary testing and counseling as an HIV prevention strategy. In: Gibney L, editor; DiClemente RJ, editor; Vermundet SH, editor. Preventing HIV iIn Developing Countries: Biomedical and Behavioral Approaches. New York: Plenum Press; 1999. pp. 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenberg J. Hennessy M. MacGowan R, et al. Modeling intervention efficacy for high-risk women. The WINGS Project. Eval Health Prof. 2002;23:123–148. doi: 10.1177/016327870002300201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rugpao S. Koonlertkit S. Pinjaroen S. Patterns of male condom use and risky sexual behaviors in Thai couples receiving ongoing HIV risk reduction counseling [Aabstract no. ThPeC7408]. Bangkok. XV International AIDS Conference 2004; Jul 11–16;2004 . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalichman S. The synergies of HIV treatment, adherence and prevention. Future HIV Ther. 2007;1:145–148. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitehead SJ. Chaikummao S. Uthaiworavit W, et al. HIV-discordant couples identified through screening for a clinical trial of microbicide safety: A chance to prevent HIV transmission [abstract no. ThPeC7400]. Bangkok. XV International AIDS Conference; Jul 11–16;2004 . [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karamagi C A. Tumwine JK. Tylleskar T. Heggenhougen K. Intimate partner violence against women in eastern Uganda: Implications for HIV prevention. BMC Public Health. 2006;20:284. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamb ML. Fishbein M. Douglas JM, et al. Efficacy of risk reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: A randomized controlled trial. Project RESPECT study group. JAMA. 1998;280:1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones DL. Weiss SM. Bhat GJ. Feldman DA. Bwalya V. Budash DA. A sexual barrier intervention for HIV+/− Zambian women: Acceptability and use of vaginal chemical barriers. J Multicult Nurs Health. 2004;10:27–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones DL. Weiss SM. Chitalu N. Bwalya V. Villar O. Acceptability of Microbicidal Surrogates among Zambian Women. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:147–53. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181574dbf. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones DL. Ross D. Weiss SM. Bhat G. Chitalu N. (2005). Influence of partner participation on sexual risk behavior reduction among HIV-positive Zambian women. J Urban Health. 2005;82:92–100. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schatz E. ‘Take your mat and go!’: Rural Malawian women's strategies in the HIV/AIDS era. Cult Health Sex. 2005;7:479–492. doi: 10.1080/13691050500151255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lagarede E. Auvert B. Chege J, et al. Condom use and its association with HIV/sexually transmitted diseases in tour urban communities of sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2001;15:1399–1408. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macaluso M. Demand M. Artz L. Fleenor M. Robey L. Kelaghan J. Female condom use among women at high risk of sexually transmitted disease. Family Plann Perspect. 2000;32:138–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francis-Chizororo M. Natshalaga NR. The female condom: Acceptability and perception among rural women in Zimbabwe. Afr J Reprod Health. 2003;7:101–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mantell JE. Myer L. Carballo-Dieguez A. Microbicide acceptability research: Current approaches and future directions. Social Science Medicine. 2005;60:319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holt BY. Morwitz VG. Ngo L, et al. Microbicide preference among young women in California. Women's Health. 2006;15:281–294. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammett TM. Mason TH. Joanis CL. Foster SE. Harmon P. Robles RR. Acceptability of formulations and application methods for vaginal microbicides among drug-involved women: Results of product trials in three cities. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27:119–126. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200002000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elias C. Coggins C. Acceptability research on female-controlled barrier methods to prevent heterosexual transmission of HIV: Where have we been? Where are we going? J Women's Health Gender Based Med. 2001;10:163–73. doi: 10.1089/152460901300039502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tolley EE. Eng E. Kohli R, et al. Examining the context of microbicide acceptability among married women and men in India. Cult Health Sex. 2006;8:351–369. doi: 10.1080/13691050600793071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones DL. Bhat GJ. Weiss SM. Bwalya V. Influencing sexual practices among HIV positive Zambian women. AIDS Care. 2006;18:629–634. doi: 10.1080/09540120500415371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalichman SC. Cain D. Zweben A. Swain G. Sensation seeking, alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors among men receiving services at a clinic for sexually transmitted infections. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:564–569. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyer-Bahlberg HFL. Ehrhardt AA. Exner TM, et al. Sexual Risk Behavior Assessment Schedule: Adult (SERBAS-A-DF-4) Manual. New York: Psychological Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chimbiri AM. The condom is an ‘intruder’ in marriage: Evidence from rural Malawi. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1102–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albarracin D. Johnson BT. Fishbein M. Muellerleile P. Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:142–161. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomsen SC. Ombidi W. Toroitich-Ruto C. A prospective study assessing the effects of introducing the female condom in a sexworker population in Mombasa Kenya. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82:397–402. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.019992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Satterwhite CL. Kamb ML. Metcalf C. Changes in sexual behavior, STD prevalence among heterosexual STD clinic attendees: 1993–1995 versus 1999–2000. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:815–819. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31805c751d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]