Abstract

Background

Concerns over patient safety have made adequacy of clinical supervision an important component of care in teaching settings. Yet, few studies have examined residents' perceptions about the quality and adequacy of their supervision. We reanalyzed data from a survey conducted in 1999 to explore residents' perspectives on their supervision.

Methods

A national, multispecialty survey was distributed in 1999 to a 14.5% random sample of postgraduate year 2 (PGY-2) and PGY-3 residents. The response rate was 64.4%. Residents (n = 3604) were queried about how often they had cared for patients “without adequate supervision” during their preceding year of training.

Results

Of responding residents, 21% (n = 737) reported having seen patients without adequate supervision at least once a week, with 4.5% saying this occurred almost daily. Differences were found across specialties, with 45% of residents in ophthalmology, 46% in neurology, and 44% in neurosurgery stating that they had experienced inadequate supervision at least once a week throughout the year, compared with 1.5% of residents in pathology and 3% in dermatology. Inadequate supervision was found to be inversely correlated with residents' positive ratings of their learning, time with attendings, and overall residency experience (P < .001 for all), and positively correlated with negative features of training, including medical errors, sleep deprivation, stress, conflict with other medical personnel, falsifying patient records, and working while impaired (P < .001).

Conclusions

In residents' self-report, inadequate clinical supervision correlates with other reported negative aspects of training. Collectively, this may detrimentally affect resident learning and patient safety.

Introduction

Supervision by an experienced medical practitioner has long been considered the sine qua non of resident training and professional development. This careful professional guidance enables students and residents to step gradually into the role of professional decision maker under the tutelage of a more seasoned, experienced mentor. In this system, highly technical learning occurs, and the habits of day-to-day medical practice can be rehearsed. Learning the mechanics of patient care under supervision enhances patient safety, helps prevent unnecessary medical errors, and lays the foundations for the public trust in physician competence.

Background and Literature Review

In spite of the general consensus on the importance of quality clinical supervision, as recently as 2000, Kilminster and Jolly1 stated that “current supervisory practice in medicine has very little empirical or theoretical basis.” Indeed, in their extensive review of supervision, they found they had to draw heavily on the literature from nursing, allied health, education, psychology, counseling, and social work, where they found much more discussion of models and theoretical approaches than in medicine.

Although medical journals now offer a number of articles on the topic, most are anecdotal or descriptive in nature and are often limited to a single site or specialty. Few comprehensive, multispecialty reviews on supervisory practices exist, and virtually no studies have queried residents themselves about the nature and adequacy of their own clinical supervision. Few authors have offered empirical evidence of the effectiveness of supervision, and still fewer have attempted to define or elaborate theoretical models. An important exception to this is the thoughtful effort of Kennedy et al2 to develop a conceptual model and typology of clinical supervision aimed at informing and guiding both policy and research, especially as it relates to the relationship between supervision and safety.

Busari et al3 have offered a glimpse of residents' views regarding supervision. Their survey of 38 pediatric residents found that most residents in their study rated the supervision they received favorably. The same residents were able to differentiate what they considered to be poor supervisory practice from that of high-quality supervision. Residents noted defining characteristics of good supervisory practice, including attending physicians who established a good learning environment (approachable, nonthreatening, enthusiastic), who allowed autonomy appropriate for the level of the resident's experience and competence, who stimulated residents to learn independently, and who gave clear explanations and reasons for their opinions. Characteristics of inadequate supervision included: deficiencies in coaching for clinical skills and procedures, ineffective communication skills, poor clinical decision making, and failing to use principles of cost-appropriate care.

The role of inadequate supervision in medical errors and adverse patient outcomes gained national attention after the public furor over the death of Libby Zion in a New York teaching hospital in 1994. As a result, the New York State Board of Health established new regulations governing supervision and resident work hours.4 Subsequently, the publication of To Err is Human by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) revealed startling figures for medical error in the practice of medicine, alarming the public and galvanizing both the nation and the profession to more closely examine the causes and consequences of medical error.5

In early 2009, the IOM's report on Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety6 reviewed the literature on the effects and consequences of the 80-hour limit on duty hours established in 2003 by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).7 In general, the IOM report was critical of residency training oversight and suggested tighter control and supervision of the review process, along with a number of other recommendations.

In June 2009, ACGME hosted an Invitational Congress on Duty Hours, at which an ACGME Task Force on Duty Hours heard position papers on this issue from more than 100 medical organizations. Common themes in presentations from a wide variety of specialties included the complexities of implementing the 2003 ACGME duty hour standards, and the unproven nature and high projected cost of many of the IOM Consensus Committee's recommendations. The presenters called on the task force to introduce flexibility into the process. Representatives from a number of specialties also highlighted the importance of supervision in promoting patient safety and voiced support for the IOM recommendations for enhanced supervision. A final set of recommendations by the ACGME task force is expected in 2010.

As the ferment over the effect of resident work hours and sleep deprivation on clinical performance and medical errors continues, the ACGME Task Force on Duty Hours is currently seeking evidence-based data on the role of supervision in patient safety to set future policy.8 To respond to this need, we report here on the self-expressed views of residents in training concerning the adequacy of their own supervision. For this report, we make use of previously unpublished but recently reanalyzed data from our 1999 national multispecialty study of residency training in the United States.

Methods

Sample

In April 1999, the authors conducted a large-scale national multispecialty survey of postgraduate year 1 (PGY-1) and PGY-2 residents in the United States regarding their learning and work environments during their current residency year (1998–1999). A 14.5% random sample of all first- and second-year residents (N = 6106) was selected using the Graduate Medical Education Database, secured as part of the annual survey of Graduate Medical Education programs by the American Medical Association.9 Residents from Puerto Rico and some smaller specialties were not included. Deaths, residents in the wrong training year, nondeliverable surveys, and early departures from the residency programs accounted for deletions from the sample, leaving 5616 potential respondents.

A 5-page questionnaire asking about a variety of learning and work-related experiences was mailed to the identified residents with a return envelope and a postcard indicating the return of the questionnaire, which was mailed back separately. This allowed residents to remain anonymous. Residents in the sample who did not return the postcard were sent 3 follow-up mailings, and program directors were mailed a letter asking them to encourage their residents to respond.

Supervision Questions

Included in the survey was the question, “During this year, how often, if ever, did you care for patients WITHOUT what you consider adequate supervision from an attending physician?” Respondents were asked to rate their supervision along a 6-point scale, where 1 = “Never”; 2 = “Less than once a month”; 3 = “At least once a month”; 4 = “At least once a week”; 5 = “More than once a week”; and 6 = “Almost daily.” A separate but related question asked residents how many hours per week they spent with an attending physician. Finally, residents were asked to rate their year of residency in terms of “contact with attending physicians” and “quality of time with attendings” on a scale of 1, “poor,” to 7, “excellent.” Means, medians, and standard deviations were calculated for a number of relevant variables, including sex, level of training, and medical specialty. Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS)-PC (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) by means of graphs and using Kendall τ-b or Spearman correlations as appropriate.

Results

Of the 5616 residents surveyed, 3604 (64.2%) responded. Demographic and specialty distributions approximated national figures.9

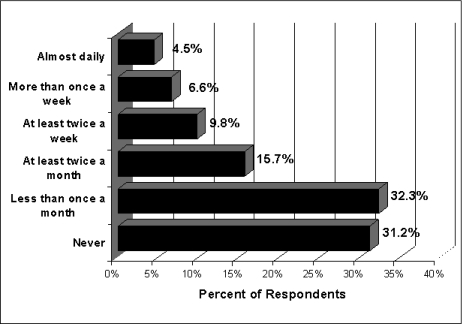

figure 1 displays residents' responses to the question regarding how often they had worked without adequate supervision. Nearly one-third (31%) of the residents stated that they had never felt that they were without adequate supervision, whereas another third (32%) said that they had experienced inadequate supervision less than once a month. Of the remaining respondents, 16% said they had experienced inadequate supervision more than twice a month, 10% at least once a week, 6.6% more than once a week, and 4.5% almost daily. For the analyses that follow, responses were scaled from 1 (never) to 6 (almost daily).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Residents' Responses to the Question: “During this Year, How Often, If ever, Did You Care for Patients WITHOUT What You Considered to Be Adequate Supervision From an Attending Physician?”

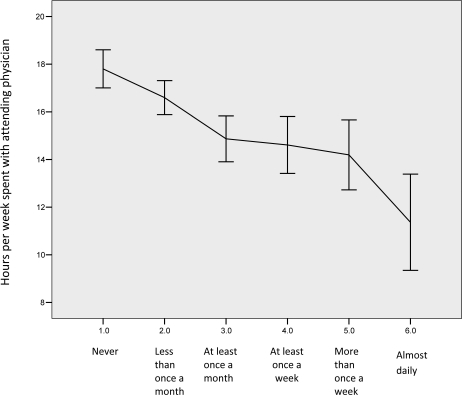

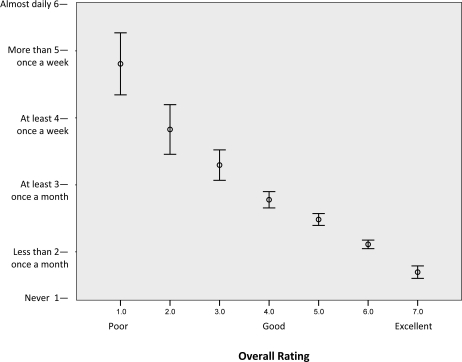

figure 2 shows the relationship between reports of working without adequate supervision and residents' reports of the average time they spent each week with attending physicians. Residents reporting more time each week with an attending physician were less likely to say that they had worked without adequate supervision than were residents who reported fewer weekly hours with an attending physician (P < .001). figure 3 shows that reports of working without adequate supervision were also strongly related to residents' ratings of satisfaction with their overall residency experience. Those reporting more time working without adequate supervision gave noticeably lower ratings to the overall residency experience (r = −0.37; P < .001).

Figure 2.

Residents' Ratings of How Often They Worked “Without Adequate Supervision” Compared with Their Reports of Weekly Hours with Attending Physician (95% Confidence Intervals Shown)

Figure 3.

Residents' Ratings of How Often They Worked “Without Adequate Supervision” Compared with Ratings of Quality of Time with Attending Physicians (95% Confidence Intervals Shown)

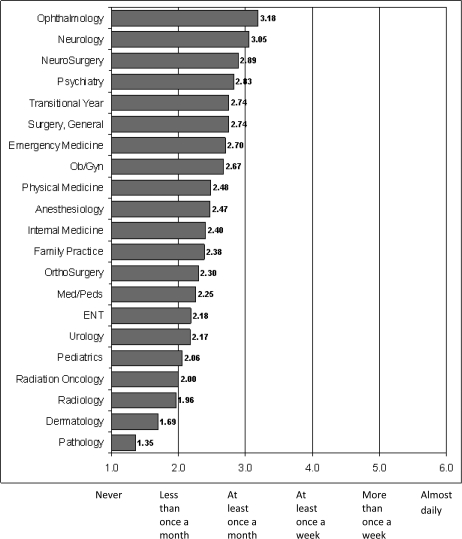

Residents in the specialties of ophthalmology, neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry were most likely to report having cared for patients without adequate supervision, whereas residents in pathology, dermatology, and radiology were least likely to report having had this experience (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Residents' Average Ratings of How Often They Worked “Without Adequate Supervision” By Specialty

Variables Associated With Reports of Working Without Adequate Supervision

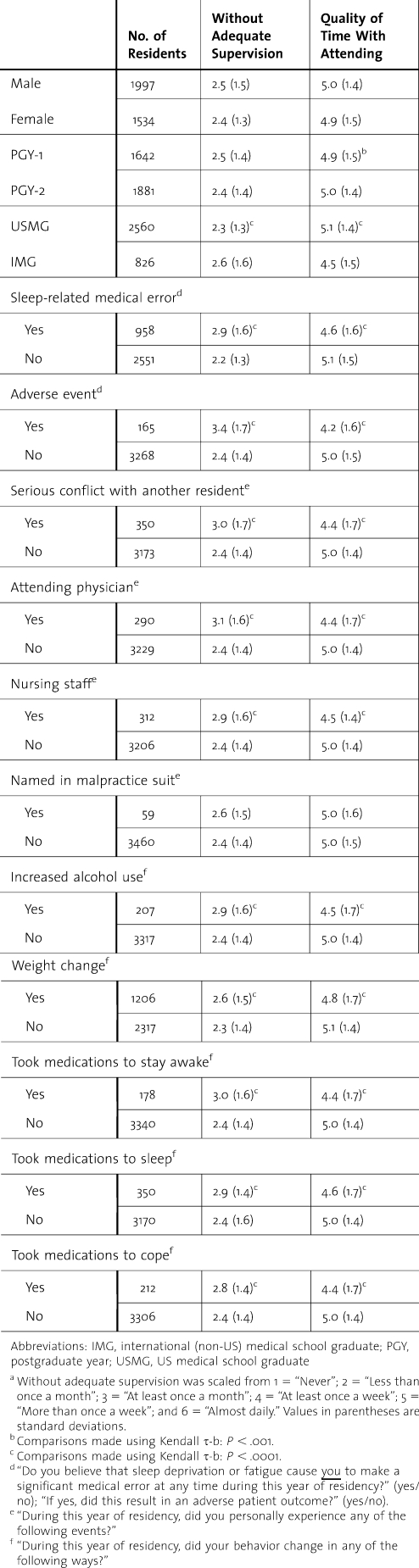

table 1 presents comparisons of reports of working without adequate supervision and ratings of quality of time spent with an attending physician, compared with other variables included in the survey. Residents' ratings of working without adequate supervision and quality of time with attendings did not differ by sex, and it showed only a marginal relationship to year of postgraduate training. On the other hand, US medical school graduates reported less time without adequate supervision and rated the quality of the time they spent with an attending physician higher than residents who graduated from medical schools outside the United States (P < .001).

Table 1.

Associations Between Residents' Report of Residency Experience and Means and Standard Deviations of Their Ratings of How Often They Worked “Without Adequate Supervision” and “Quality of Time With Attending Physician”a

Residents who reported having made a significant sleep-related medical error were substantially more likely to report having worked without adequate supervision (P < .001) and to rate the quality of their time with an attending physician lower than residents who did not report a sleep-related error (P < .001). These differences are even more pronounced for residents who said their error resulted in an adverse patient event (P < .001). No correlation with self-reported supervision was found for the small subset of residents who reported being named in a malpractice.

Residents who reported having had a serious conflict with an attending physician, another resident, or a member of the nursing staff were significantly more likely to report seeing patients without adequate supervision and to provide lower ratings of quality of time with an attending physician (P < .001). In addition, residents who reported increased use of alcohol, significant weight change, or use of medications either to stay awake, to help them sleep, or to help them cope with the residency were all more likely to report working without adequate supervision and give lower ratings of the quality of the time they spent with attending physicians (P < .001).

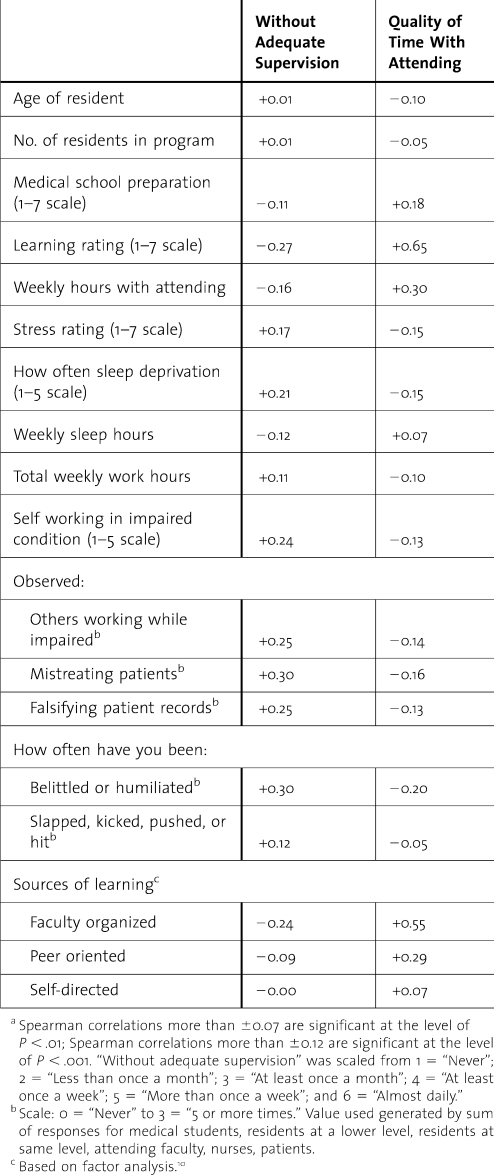

Spearman Correlations

table 2 displays Spearman correlations between reports of having worked without adequate supervision, ratings of quality of time with attending physicians, and other variables included in the survey. Relationships between these variables and either the age of the resident or the size of the residency program were small to nonexistent. Residents who gave higher ratings of the adequacy of their medical school preparation (1–7 scale) were less likely to report working without adequate supervision and more likely to give a higher rating of the quality of the time they spent with attending physicians (1–7 scale). Respondents who reported working without adequate supervision gave lower ratings to their learning experience during residency and reported fewer contact hours with attending physicians overall (P < .01). A high rating of “quality of time with attendings” showed strong positive relationships with both ratings of learning and actual time spent with attending physicians (P < .001).

Table 2.

Spearman Correlations Showing Associations Between Residents' Reports of Residency Experience and Their Ratings of How Often They Worked “Without Adequate Supervision” and “Quality of Time With Attending Physician” (n = 3533)a

Working without adequate supervision was positively associated with higher ratings of self-assessed stress, sleep deprivation, total weekly work hours, and reports of having worked while in an impaired condition (P < .001). These same variables were negatively related with ratings of quality of time with an attending physician (P < .001). Those reporting having worked without adequate supervision were also more likely to report having observed others working in an impaired condition, mistreating patients, and falsifying patient records, and were more likely to report that they personally had been belittled and humiliated, or physically assaulted while working (P < .001). As above, ratings of “quality of time with attendings” were inversely related to reports of these negative residency experiences (P < .001).

Finally, in a previous paper we identified 3 sources of learning during residency training: “faculty organized,” “peer oriented,” and “self-directed.”10 Residents who reported working without adequate supervision reported less learning from faculty and peers (P < .001), whereas quality of time with attending physicians showed a strong positive relationship with these 2 sources of learning (P < .001).

Discussion

Although most residents reported that they usually had worked under adequate supervision while seeing patients, just more than 35% reported that they had worked without what they thought was adequate supervision more than once a month, with more than 11% stating that this occurred more than once a week. Reports of working without adequate supervision varied widely across specialties and were shown to be positively related to reports of medical errors, sleep deprivation, working while impaired, conflicts with medical staff, observations of others engaging in unethical conduct, and increased use of alcohol, as well as medications to sleep, stay awake, and cope during residency. Working without adequate supervision was negatively related to ratings of learning, time spent with attending physicians, quality of time with attending physicians, and overall satisfaction with the residency experience.

The good news is that for most residents, working without adequate supervision is a relatively rare occurrence, suggesting the system works most of time. These findings are further supported by the higher ratings for time with attendings and quality of their time with attendings given by these same residents. The bad news is that when residents perceive they are receiving inadequate supervision, it appears to be concurrent with a wide variety of additional negative experiences in the training. It also appears to be associated with residents expressing dissatisfaction with their overall residency experience.

In 1998, Daugherty and Baldwin11 created a regression model for resident satisfaction with their learning experience during the PGY-1 year (R2 = 0.36), in which residents placed contact with their attending physicians highest among the factors contributing to their satisfaction (+0.318; P < .001). In spite of other evidence suggesting that residents actually learn more from their peers, they seem to value contact with attending physicians the most.11

Our study asked residents to provide self-ratings of the adequacy of their supervision. At the same time, the question of what constitutes “adequate” supervision is not an easy one. We suspect that residents' sense that supervision is inadequate stems from a combination of (1) the actual oversight provided by the attending physicians and (2) residents' perceived need for that oversight. Providing adequate supervision is not as simple as just the amount of time that attending physicians spend with residents. We think it likely that residents want more supervision for clinical tasks that are technically difficult, or where the perceived dangers due to error are high. Simple tasks require less supervision. Thus, inferences in reports regarding inadequate supervision across specialties could result from differences in procedural difficulty and perceived danger. Further, we suspect that any new task is likely to require more supervision than one that has been performed before, and that residents' felt need for supervision decreases as their sense of their own competence increases. The kind of supervision residents want early in their training and the supervision they wish for later in their training are likely quite different in how much direction they seek and how much control over their actions they are allowed.

In 1977, after conducting in-depth interviews with 2 groups of residents throughout an entire year, Bucher and Stelling12 noted that residents not only need but actively seek autonomy and independence in their development and in their work. At the beginning, when new and unsure, they eagerly seek and appreciate nearly everything they can learn from their more experienced colleagues and superiors. This period is reminiscent of the seminal work of Lev Vygotsky,13 who posited that learning functions best in a “zone of proximal development.” The teacher's job is to make available the necessary tools and the proper conditions that will enable the learner to make his or her own discoveries. Proper supervision requires changing these tools and conditions as the learner's capacity changes, a process Farnan et al14 refer to as “a 2-way street.”

According to Bucher and Stelling,12 over time, residents seek to strike out on their own and want more control over their own work and learning experiences. In this process, trainees rely predominantly on their evaluation of their own and others' performance and behavior, and they begin to actively discount criticism and control from others. Often this takes the form of simply preselecting the cases to be discussed and choosing the attending most likely to corroborate the resident's decisions. The process thus becomes self-validating. As residents perceive themselves as more and more competent, they feel more and more confident of judging their own performance. Once this point is reached, supervision that seemed essential earlier may come to be regarded as an annoying interference.

Limitations

Our study shared the limitations for all survey research. Surveys do not permit inferences of causality, and the findings of this study must be limited to those of association and correlation. In addition, the results are based on a reanalysis of 10-year-old data from a large, cross-sectional survey and are dependent on the self-report of residents and on ratings of a single item, without a specific definition of supervision. There always is concern over the validity of self-report data, especially when it is retrospective, although the psychological validity of perceptions has been well established. The response rate (64%), although quite high for this population, still allows for the possibility that residents who responded are different from those who did not, although in this sample and for this study, we specifically found that residents who responded early in the survey period provided data that did not differ significantly from those who responded toward the end. We believe the limitations are mitigated by our experience with survey methodology; our large, random, demographically representative, national sample; and the consistency of our findings and the prior reports of others.

Because the current study uses self-reported data collected from residents at a single point in time, it is not possible to determine whether lack of supervision led to the other reported negative experiences, whether these negative behaviors resulted from the inadequacy of supervision, or whether the relationship is more complex than a simple linear, causal one. We suspect, but cannot prove, that working without adequate supervision may be a sign of a breakdown in the education and services experience in residency. Lack of supervision, then, may not be so much a cause as a possible sign that something in the residency is not working well. We have addressed this issue in another paper,15 comparing this situation with the signs of social disorganization found in fragmented communities, as described in the well-known “Broken Windows” theory.16 Although this kind of disorganization is certainly not the norm in residency training, it appears prevalent enough to be cause for concern. Thus, we do not think inadequate supervision can or should be addressed in isolation, but should be viewed in the context of the residency program as a whole. It is clear that we need additional research on this complex issue.

Conclusion

When residency programs are not working well, both patients and residents are placed at risk. Patients are put at risk because residents may not be receiving the guidance they need to provide optimum patient care and to avoid making errors. Residents are at risk because they may not be learning what they should be learning to become independent practitioners. The goal of residency training should not be only to develop their competence to care for patients in the hospital today, but to develop the capability to care for their patients of tomorrow.

References

- 1.Kilminster S. M., Jolly B. C. Effective supervision in clinical practice settings: a literature review. Med Educ. 2000;34(10):827–840. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy T. J., Lingard L., Baker G. R., Kitchen L., Regehr G. Clinical oversight: conceptualizing the relationship between supervision and safety. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(8):1080–1085. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0179-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busari J. O., Weggelaar N. M., Knottnerus A. C., Greidanus P. M., Scherpbier A. J. How medical residents perceive the quality of supervision provided by attending doctors in the clinical setting. Med Educ. 2005;39(7):696–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Limited Resident Working Hours and Standards for Resident Supervision. NY Stat §405.4(b)(6).

- 5.Kohn L. T., Corrigan J. M., Donaldson M. S., editors. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC:: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ulmer C., Wolman D. M., Johns M. M. E., editors. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Washington, DC:: National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Board of Directors approved resident duty hour standards at February meeting. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/newsReleases/newsRel_02_17_03.pdf 2003 Accessed February 9, 2010.

- 8.Nasca T. J. Request for proposal for comprehensive literature review and analysis of residency training and duty hours experience. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/home/acgme_nascaletter_RFP.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2010.

- 9.Miller R. S., Dunn M. R., Richter T. Graduate medical education. JAMA. 1999;282(9):855–860. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daugherty S. R., Baldwin D. C., Jr How residents say they learn: a national, multi-specialty survey of first and second year residents. ACGME Bulletin. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/bulletin/bulletin11_07.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Daugherty S. R., Baldwin D. C., Jr, Rowley B. D. Learning, satisfaction, and mistreatment during medical internship: a national survey of working conditions. JAMA. 1998;279(15):1194–1199. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bucher R., Stelling J. G. Becoming Professional. London, UK:: Sage Publications; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vygotsky L. Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky. New York, NY:: Plenum; 1998. pp. 187–205. Vol 5. Hall MJ, trans. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farnan J. M., Humphrey H. J., Arora V. Supervision: a 2-way street. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(10):1117. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.10.1117-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baldwin D. C., Jr, Daugherty S. R. Interprofessional conflict and medical errors: results of a national multi-specialty survey of hospital residents in the US. J Interprof Care. 2008;22(6):573–586. doi: 10.1080/13561820802364740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson J. Q., Kelling G. L. Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety. New York, NY:: Atlantic Monthly; 1982. [Google Scholar]