Abstract

Objective

To assess if the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict MODE Instrument predicts residents’ performance.

Study Design

Nineteen residents were assessed on the Thomas-Kilmann conflict modes of competing, collaborating, compromising, accommodating, and avoiding. Residents were classified as contributors (n = 6) if they had administrative duties or as concerning (n = 6) if they were on remediation for academic performance and/or professionalism. Data were compared to faculty evaluations on the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competencies. P value of < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Contributors had significantly higher competing scores (58% versus 17%; P = .01), with lower accommodating (50% versus 81%; P 5 .01) and avoiding (32% versus 84%; P = .01) scores; while concerning residents had significantly lower collaborating scores (10% versus 31%; P = .01), with higher avoiding (90% versus 57%; P = .006) and accommodating (86% versus 65%; P = .03) scores.

There were significant positive correlations between residents’ collaborating scores with faculty ACGME competency evaluations of medical knowledge, communication skills, problem-based learning, system-based practice, and professionalism. There were also positive significant correlations between compromising scores and faculty evaluations of problem-based learning and professionalism with negative significant correlations between avoiding scores and faculty evaluations of problem-based learning, communication skills and professionalism.

Conclusions

Residents who successfully execute administrative duties are likely to have a Thomas-Kilmann profile high in collaborating and competing but low in avoiding and accommodating. Residents who have problems adjusting are likely to have the opposite profile. The profile seems to predict faculty evaluation on the ACGME competencies.

Introduction

Conflict is described as a social situation where 2 parties struggle with one another due to incompatibilities in perspectives, beliefs, goals, or values; this struggle impedes the achievement of predetermined goals or objectives.1 It has been debated whether conflicts are detrimental or necessary for social functioning. Some researchers have argued that the few positive effects of conflict are outweighed by the negative effects, while others have suggested that conflict can result in better understanding and adoption of effective teamwork. It is generally agreed that conflicts are inevitable and need to be managed to avoid negative impacts on the individual or organization.2 When characterized by a process of cooperation and joint resolution, conflict can create a diverse environment that fosters growth and improves relationships.

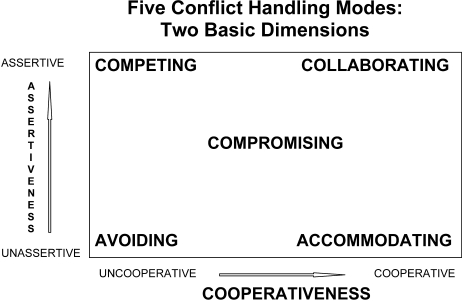

Blake and Mouton3 developed the Managerial Grid, a framework of 5 conflict responses graded on 2 dimensions: concern for people and concern for production. Building on Blake and Mouton's work, Kilmann and Thomas4 in 1974 described conflict behaviors using the 2 dimensions of assertiveness and cooperativeness (figure 1). Assertiveness is the extent to which an individual tries to satisfy his own concerns. Cooperativeness is the extent to which an individual tries to satisfy others' concerns. Within these dimensions, 5 conflict-handling modes were described, which paralleled those of Blake and Mouton: competing, accommodating, avoiding, collaborating, and compromising (table 1). These 5 behaviors form the foundation of the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict MODE Instrument (TKI), used to assess conflict styles.5

Figure 1.

The 5 Conflict Styles Graded on 2 Dimensions: Assertiveness and Cooperativeness. (Source: Figure adapted from Thomas [1976]).5

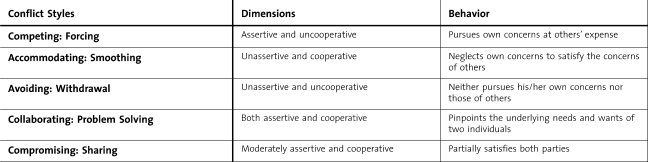

Table 1.

The 5 Conflict Styles Developed by Thomas and Kilmann and the Prospective Behaviors

Conflict management is based on the principle that conflicts, while unavoidable, can be managed to generate positive outcomes. Effective management requires the ability to evaluate the potential consequences of action, as well as understanding the motivations of one's self and the other parties. Effective management includes choosing the most appropriate conflict strategy given the situation (table 1). For example, the strategy of competing is best used when quick, decisive action is vital; when an unpopular course of action needs implementing; or to protect against being taken advantage of by another entity. Compromising works best when opponents of equal power must enter into negotiations that require making concessions to achieve a common goal. Collaborating, which takes significant time and energy, is beneficial in dealing with important issues or relationships that cannot be compromised. Accommodation is best utilized in situations in which it is important to satisfy others, show reasonableness, build up social credits, or preserve harmony. Avoidance is effective in situations where tension needs to be reduced, when an individual is lower on the power hierarchy, or when others can resolve the conflict more effectively. Although individuals are capable of utilizing all 5 strategies, for most, 1 or 2 strategies usually remain the “preferred” methods.

Several studies6–8 have suggested a positive correlation between emotional intelligence (EI) and conflict resolution. Emotional intelligence has been consistently shown to correlate with successful leadership skills.9–13 Unlike intelligence quotient, which remains stable over time, EI is flexible and changeable with training and counseling.11 There are 2 main components of EI: The first is self-competence, which includes self-awareness, self-regulation, and motivation. The second is social competence, which includes social awareness, empathy, and relationship management. The skills required to effectively manage conflict parallel the components of EI. In conflict situations, self-competence allows an individual to have knowledge of their weaknesses and preferences, to be able to control their emotions, and to maintain the drive to reach goals independent of rewards. Effective conflict resolution then requires that the individual be aware of the conflict styles of the opponent, as well as empathize with the perspective and needs of the adversary, in order to facilitate desirable behavior and outcomes.

The US health care system creates potential for conflicts given the multidisciplinary approach to patient care, stressful environment, multiple roles, hierarchies, extended work hours, and emotional demands. Recognizing that conflict management is crucial to maintaining productivity, patient safety, and job satisfaction for health care professionals, The Joint Commission issued a Sentinel Event Alert14 in 2008, which outlined recommendations on skills-based training and coaching, relationship building, collaborative practice, feedback on unprofessional behavior, and conflict resolution.

Residency training is a conflict-prone period because of demands related to patient care, extended work hours, learning demands, evaluations, and hierarchies in the workplace, as well as personal and family matters.15 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competencies16 of interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and system-based practice address the development of skills that allow residents to successfully negotiate conflict. Surveys have shown that residents have conflicts with individuals in 3 main categories: superiors, peers, and patients.15,17 The reported ethical conflicts fall into 5 categories: honesty, respect of patient autonomy, doing no harm, understanding the limits of one's competence, and critically evaluating peers.

It is crucial that residents are adequately taught skills to adapt to their positions and be effective team members in order to optimize patient safety and quality of care. Few studies exist that examine conflict styles of residents or modes of practicing that could facilitate the development of an appropriate training program. In contrast, there are several studies18–21 using the TKI to understand conflict management styles in nurses and articles22–27 providing models of conflict management and resolution for practicing physicians and academic leaders. In the PubMed database, we searched the literature using “conflict styles” (222 hits), “Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI)” (2 hits), and “conflict resolution in resident physicians” (3 hits). We found only 1 study27 on principles of conflict resolution in surgeons, and none involving residents.

From the perspective of individual development and optimizing team building during residency training, it is important to investigate conflict styles and resident performance. This is a pilot study to assess the TKI in predicting residents' performance during training. Our hypothesis was that the TKI would show significant associations with residents' performance during training and faculty evaluations using the ACGME competencies.

Materials and Methods

The Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles has a 4-year, ACGME-accredited residency program with 5 residents per year. The department consists of 20 full-time faculty members and a larger cadre of private clinicians who admit their patients to the medical center.

The TKI is an ipsative or forced-choice measurement tool made up of 30 statement pairs, each illustrating 1 of the 5 conflict modes. Respondents must choose 1 statement from each pair that best describes how they respond to conflict situations. Each conflict mode is represented a total of 12 times in the TKI; hence a maximum of score of 12 can be achieved for each mode. Norms for the TKI were developed from a group of managers at middle and upper levels of business and government organizations.4 Scores are compared against the norm frequency to develop percentiles and are categorized as high or low for each conflict mode if they were in the upper or lowest 25th percentile, respectively. The test-retest reliability of the TKI ranges from 0.61 to 0.68, and convergent validity has been determined.4

The residency program embarked on a development program to improve team building, communication skills, and teaching abilities of the residents. As part of this program, conflict styles of the residents were assessed. Residents were asked to complete the TKI as they would respond at work and not at home. Our study is based on a convenience sample of 19 residents in the academic year 2007–2008 who took the TKI and who had their conflict mode percentiles calculated. Exempt status was granted by the Institutional Review Board since only de-identified information of educational assessments was used for this study. Residents were asked if their evaluations and scores could be used for this study.

Faculty evaluate residents twice yearly using a standardized evaluation form based on the 6 ACGME competencies of patient care, medical knowledge, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, practice-based learning and improvement, and systems- based practice. This evaluation is done electronically utilizing an online program called New Innovations. The evaluations completed by 25 faculty members for the academic year 2007–2008 were compiled for this study. Likewise the standardized, postgraduate year-adjusted Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology (CREOG) examination scores for each resident was obtained for the academic year 2007–2008.

For the purpose of this study, residents were classified as contributors (n = 6) if they provided major administrative service to the program. Contributors were residents who were democratically elected as the administrative chief residents and residents who voluntarily implemented the residency journal club and the medical students' clerkship. Concerning (n = 6) residents were those placed on remediation because of academic and professionalism matters. In 2 cases, residents exhibited abandonment by leaving their clinical duties without obtaining approval. In both cases, the individuals felt very “stressed” because of other issues and just could not “handle it.”

A Student t test, χ2 test, and Spearman rank correlation were used to compare and assess the association between conflict style scores with faculty evaluations, CREOG scores, and residents' categorization as indicated. A P value of less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 19 residents in the program during the academic year 2007–2008 formed the basis of the study. Fifteen of the residents (79%) were women and 4 (21%) were men. Female residents had a significantly higher accommodating mode with no other differences noted on the other modes. Eight residents (42%) each were Asian American or non-Hispanic white, and there was 1 African American, 1 Native American, and 1 Latino resident. Non-Hispanic whites had significantly higher competing percentiles but lower accommodating and avoiding percentiles (table 2).

Table 2.

Significant Demographic Differences in Conflict Styles Among the Cohort of Residents (n = 19)

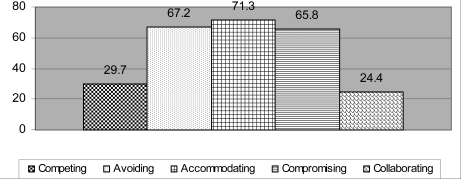

The mean percentile scores of all residents for conflict styles are illustrated in figure 2. The preferred conflict style for residents as a group was accommodating, followed by avoiding. The least preferred conflict style was collaborating, followed by competing. The most common quartiles were high accommodating with 15 residents (79%), high avoiding with 10 residents (53%), low collaborating with 10 residents (53%), high compromising with 6 residents (32%), and low competing with 6 residents (32%).

Figure 2.

Mean Percentiles of Residents on Conflict Styles (n = 19)

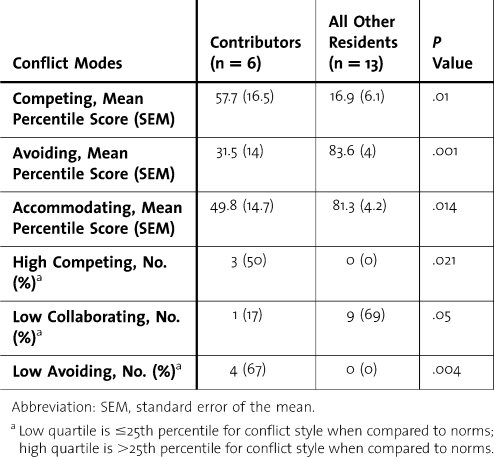

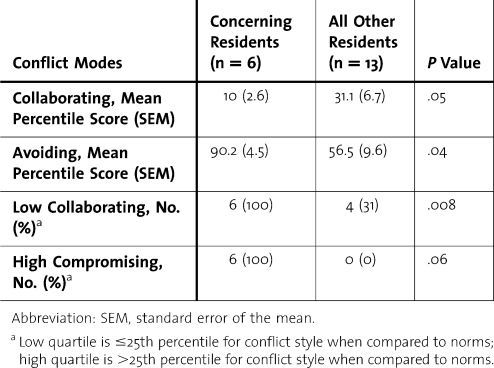

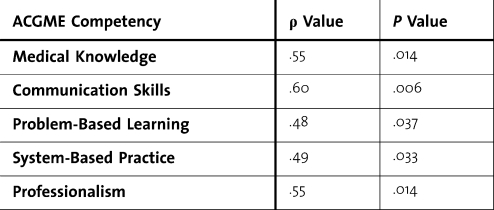

Contributors, compared to all other residents, had significantly higher competing scores, with lower accommodating and avoiding scores (table 3). Concerning residents, compared to all other residents, had lower collaborating with higher avoiding scores (table 4). Contributing residents compared only to concerning residents had significantly higher collaborating and lower avoiding and accommodating percentiles (table 5).

Table 3.

Comparison of Conflict Modes Scores of Contributing Residents Versus All Other Residents

Table 4.

Comparison of Conflict Modes Scores of Concerning Residents Versus All Other Residents

Table 5.

Comparison of Conflict Modes of Contributors Versus Concerning Residents Only

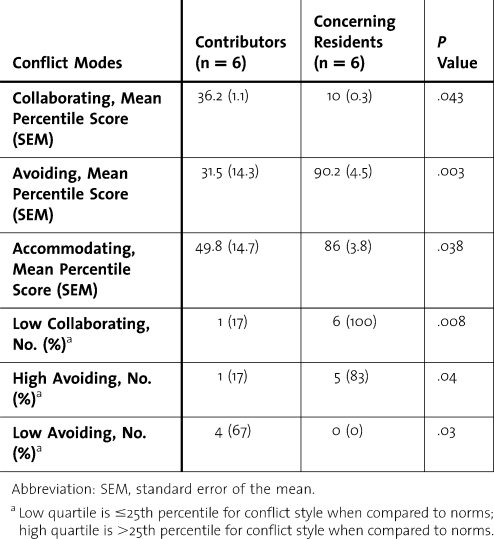

Table 6 shows that there were significant positive correlations between collaborating scores and faculty evaluations of 5 ACGME competencies. Compromising scores also had significant positive correlations with faculty evaluations on problem-based learning (r = 0.59, P = .01) and professionalism (r = 0.50, P = .03). There were also significant negative correlations between avoiding percentiles and faculty evaluations on problem-based learning (r = −0.51, P = .03), communication skills (r = −0.53, P = .02), and professionalism (r = −0.54, P = .02).

Table 6.

Correlation Between Faculty Evaluations of Residents Using Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Competencies and Residents' Collaborating Style Scores: Spearman Correlations

Discussion

In this study, conflict styles seemed predictive of residents' behavior during residency. Contributors had significantly higher competing scores with lower avoiding and accommodating scores, while concerning residents had significantly lower collaborating scores. The goal of using the competing conflict style is to win without concern for others' goals. It is appropriately used when a tough decision must be made in a timely fashion. A study by Watson and Hoffman28 found that low-level managers often adopt competitive stances in negotiation compared to the collaborative stances seen in high-level managers. This is comparable to the dynamics of a residency program in which residents may take the role of low-level managers and the faculty that of high-level managers. Dyadic effectiveness or constructiveness is defined as the extent to which conflict behavior produces better outcomes for the organizational dyad by resolving the conflict and improving the relationship between the parties. Van De Vliert et al29 showed through field studies that the combination of competing followed by collaborating style leads to the most effective negotiations or dyadic effectiveness. This is compatible with our findings of higher competing scores in contributors and lower collaborating scores in concerning residents.

Faculty evaluations of residents were also predicted by conflict mode style. The collaborating conflict style showed positive correlations with faculty scores on 5 ACGME competencies. Collaboration is characterized by high assertion and cooperation (figure 1), which enables a win-win solution via open dialogue. Residents with high compromising scores were also rated higher on professionalism and problem-based practice by faculty. The compromising style involves moderate assertiveness and cooperativeness. Conversely, the avoiding conflict style correlated with lower evaluations on professionalism and problem-based learning. Avoidance is characterized by both low assertiveness and cooperation (figure 1), which leads to neither party's needs being met. In such circumstances, communication is not attempted and resolution of the conflict is delayed. Our findings suggest that faculty give residents higher evaluations if the residents are assertive and cooperative. This parallels findings by Lee et al,30 which demonstrated a positive association between higher clerkship grades and medical students who were more assertive and less reticent.

Another factor in conflict style preference is culture. In our study, non-Hispanic white residents were found to have higher collaborative and lower accommodative scores compared to their Asian American colleagues. This is comparable to a study30 showing that non-Hispanic white medical students, when compared to underrepresented minority and Asian American medical students, reported higher levels of assertiveness and lower levels of reticence. These findings may be attributed to culturally influenced communication skills. It has been shown31 that non-Hispanic white American culture places importance on the act of talking, associating it with high cognitive function, while quietness is considered mental passivity. However, Asian cultures tend to use “internal speech,” with meditation and silence perceived as pathways to higher thinking.31

Sex is an important factor in conflict resolution. In our study, female residents were more likely to exhibit the accommodating conflict style, characterized by low assertiveness and high cooperativeness (figure 1). This finding is compatible with other health care studies. In female medical students, an association was found between high reticence scores and low assertiveness scores.30 A study of internal medicine residents32 showed that female residents reported more gender issues and chose less-assertive behaviors in clinical scenarios. Despite remarkable social changes in the last 25 years, there has been relatively little change in stereotypical gender behavior; men are still expected to be “assertive,” and women are expected to be “compassionate” and “yielding.”33 Although female residents may be in positions of authority and may direct their patients' care, they may avoid using assertive styles that lead to potential “social penalties” for nonconformation to stereotypical female roles.32

As a group, residents most commonly utilized accommodating styles, followed by avoiding styles. The least preferred conflict style was collaborating, followed by competing. Previous studies have demonstrated the influence of organizational status level on conflict-style selection.33,34 Although studies differ in which conflict style is associated with higher organizational status, a positive correlation does exist between higher organization level and an increase in aggressiveness. Those in lower status levels more often use avoiding and accommodating styles.33,34 Similarly, nurses in older studies19,20 had a preferred conflict style of compromise, while more-recent studies18,21 show nurses using primarily accommodating followed by avoiding conflict styles. In this circumstance, lower-level status increases the likelihood that less-aggressive styles will be chosen to resolve conflict. Considering the high number of nurse-resident interactions required to carry out effective patient care, conflict resolution between these team members is crucial. Since organizational status affects conflict style, a study examining the conflict styles used in nurse-resident interactions is important.

Unique stressors felt by residents as a group may modify their conflict style. A force perceived as a threat can decrease problem-solving effectiveness, leading to a phenomenon known as “group think,”35 characterized by group members trying to decrease conflict by reaching consensus without critically analyzing or discussing the situation. This leads to lower problem-solving efficacy and creativity. As the free flow of ideas is blocked, all group members begin to take on similar beliefs and attitudes. Supervisors should be aware of the possible role of group dynamics and characteristics on residents' behavior.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. First, there are concerns about the alpha reliability of the TKI, though many believe that it provides useful clinical data.4 Second, the sample size is small and represents only residents from 1 institution in southern California; therefore, the results may not be generalizable. Results of similar studies from other areas may be influenced by regional culture, residency type, and gender and ethnic mix, among other factors. A review of the literature shows that all previous studies using the TKI in health care providers8,18–21 have referenced norms developed from a group of middle- and upper-level managers in business organizations; it is possible that this is an assumption and may not be applicable to health care providers. Future studies should develop a health care provider-specific normogram with a larger sample. Finally, there may be an inherent bias in this study since the program directors collected all the information and supervised all the residents. Blinding of the original data was only possible after deidentification of the data for analysis. Although we had criteria for the definitions of contributing or concerning residents, this categorization is still subjective and not standardized. Despite these limitations, this study is important because it is the first reported study to assess conflict styles in residents and link it to performance during residency.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that larger and more inclusive studies on conflict styles in residents and members of the health care team could be beneficial. The results suggest that criteria used for residents' evaluation by faculty may reflect cultural influences apart from academic competence. A longitudinal study will be informative in assessing the influences of experience, training, and coaching on conflict styles and the impact on teamwork and patient safety. Our data suggest that residents who are successful in executing significant administrative duties in addition to training are more likely to have a Thomas-Kilmann profile that is relatively high in collaborating and competing but low in avoiding and accommodating. Residents who are having problems adjusting to the residency program are likely to have the opposite profile. The conflict modes also seem to be able to predict residents' evaluations by faculty on the ACGME competencies. Supervisors should be aware of the possible role of group dynamics and characteristics on residents' behavior, sex, race, organizational level, or cultural background that may predispose them to less aggressive conflict styles. In our residency program, all residents are taught self-awareness with instructions on emotional intelligence, including role play. Residents with concerning behavior receive individualized training, counseling, and guidance from the program director, mentors, and the organizational coach.

References

- 1.Stevahn L., King J. A. Managing conflict constructively in program evaluation. Evaluation. 2005;11(4):415. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spector P. E. Introduction: conflict in organizations. J Organ Behav. 2008;29:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blake R. R., Mouton J. S. Solving Costly Organization Conflict. San Francisco, CA:: Jossey-Bass; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kilmann R. H., Thomas K. W. Developing a forced-choice measure of conflict-handling behavior: the “Mode” instrument. Educ Psychol Meas. 1977;37(2):309–325. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas K. W. Conflict and conflict management. In: Dunnette M. D., editor. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Chicago, IL:: Rand-McNally; 1976. pp. 889–935. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jordan P. J., Troth A. C. Managing emotions during team problem solving: emotional intelligence and conflict resolution. Human Performance Publication. 2004;17(2):195–218. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordan P., Troth A. Emotional intelligence and conflict resolution: implications for human resource development. Adv Developing Human Resources. 2002;4(1):62–79. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahim M. A., Psenicka C., Polychroniou P., et al. A model of emotional intelligence and conflict management strategies: a study in seven countries. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. 2002;10(4):302–326. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor C. A., Taylor J. C., Stoller J. K. Exploring leadership competencies in established and aspiring physician leaders: an interview-based study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):748–754. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0565-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naylor C. D. Leadership in academic medicine: reflections from administrative exile. Clin Med. 2006;6(5):488–492. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.6-5-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stichler J. F. Emotional intelligence. A critical leadership quality for the nurse executive. AWHONN Lifelines. 2006;10(5):422–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6356.2006.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gewertz B. L. Emotional intelligence: impact on leadership capabilities. Arch Surg. 2006;141(8):812–814. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.8.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goleman D. What makes a leader? Harvard Business Review. 1998;76(6):93–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Joint Commission. Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/SentinelEventAlert/sea_40.htm. Accessed January 14, 2010.

- 15.Daugherty S. R., Baldwin D. C., Rowley B. D. Learning, satisfaction, and mistreatment during medical internship: a national survey of working conditions. JAMA. 1998;279(15):1194–1199. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/dutyHours/dh_dutyhoursCommonPR07012007.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2010.

- 17.Rosenbaum J. R., Bradley E. H., Holmboe E. S., Farrell M. H., Krumholz H. A. Sources of ethical conflict in medical housestaff training: a qualitative study. Am J Med. 2004;116(6):402–407. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitworth B. S. Is there a relationship between personality type and preferred conflict-handling styles? An exploratory study of registered nurses in southern Mississippi. J Nurs Manag. 2009;16(8):921–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sportsman S., Hamilton P. Conflict management styles in the health professions. J Prof Nurs. 2007;23(3):157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hendel T., Fish M., Berger O. Nurse/physician conflict management mode choices: implications for improved collaborative practice. Nurs Adm Q. 2007;31(3):244–253. doi: 10.1097/01.NAQ.0000278938.57115.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison J. The relationship between emotional intelligence competencies and preferred conflict-handling styles. J Nurs Manag. 2008;16(8):974–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harolds J., Wood B. P. Conflict management and resolution. J Am Coll Radiol. 2006;3(3):200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porter-O'Grady T. Embracing conflict: building a healthy community. Health Care Manage Rev. 2004;29(3):181–187. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200407000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaudry J., Jain A., McKenzie S., Schwartz R. W. Physician leadership: the competencies of change. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(3):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chervenak F. A., McCullough L. B. The identification, management, and prevention of conflict with faculty and fellows: A practical ethical guide for department chairs and division chiefs. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;197(6):572. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chervenak F. A., McCullough L. B. An ethical framework for identifying, preventing, and managing conflicts confronting leaders of academic health centers. Acad Med. 2004;79(11):1056–1061. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200411000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee L., Berger D. H., Awad S. S., Brandt M. L. Conflict resolution: practical principles for surgeons. World J Surg. 2008;32(11):2331–2335. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9702-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watson C., Hoffman R. L. Managers as negotiators: a test of power versus gender as predictors of feelings, behavior, and outcomes. Leadership Quarterly. 1996;7(1):63–85. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van De Vliert E., Nauta A., Giebels E., Janssen O. Constructive conflict at work. J Organ Behav. 1999;20(4):475–491. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee K. B., Vaishnavi S. N., Lau S. K. M., Andriole D. A., Jeffe D. B. “Making the grade”: noncognitive predictors of medical students' clinical clerkship grades. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(10):1138–1150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim H. S. We talk, therefore we think? A cultural analysis of the effect of talking on thinking. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;83(4):828–842. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.4.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartels C., Goetz S., Ward E., Carnes M. Internal medicine residents' perceived ability to direct patient care: impact of gender and experience. J Womens Health. 2008;17(10):1615–1621. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brewer N., Mitchell P., Weber N. Gender role, organizational status, and conflict management styles. International Journal of Conflict Management. 2002;13(1):78–94. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chusmir L. H., Mills J. Gender differences in conflict resolution styles of managers: at work and at home. Sex Roles. 1989;20(3/4):149–163. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rempel M. W., Fisher R. J. Perceived threat, cohesion, and group problem solving in intergroup conflict. International Journal of Conflict Management. 1997;8(3):216–234. [Google Scholar]