Abstract

For the last three decades significant parts of national science budgets, and international and private funding worldwide, have been dedicated to cancer research. This has resulted in a number of important scientific findings. Studies in tissue culture have multiplied our knowledge of cancer cell pathophysiology, mechanisms of transformation and strategies of survival of cancer cells, revealing therapeutically exploitable differences to normal cells. Rodent animal models have provided important insights on the developmental biology of cancer cells and on host responses to the transformed cells. However, the rate of death from some malignancies is still high, and the incidence of cancer is increasing in the western hemisphere. Alternative animal models are needed, where cancer cell biology, developmental biology and treatment can be studied in an integrated way. The zebrafish offers a number of features, such as its rapid development, tractable genetics, suitability for in vivo imaging and chemical screening, that make it an attractive model to cancer researchers. This Primer will provide a synopsis of the different cancer models generated by the zebrafish community to date. It will discuss the use of these models to further our understanding of the mechanisms of cancer development, and to promote drug discovery. The article was inspired by a workshop on the topic held in July 2009 in Spoleto, Italy, where a number of new zebrafish cancer models were presented. The overarching goal of the article is aimed at raising the awareness of basic researchers, as well as clinicians, to the versatility of this emerging alternative animal model of cancer.

Zebrafish cancer models

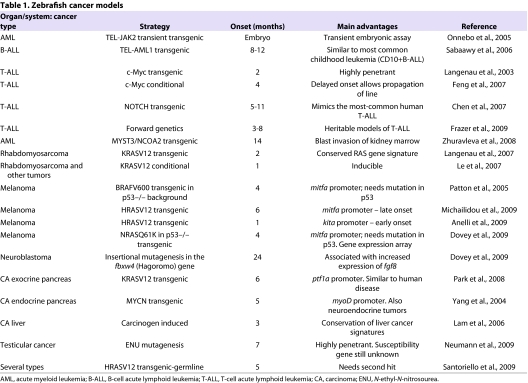

Several models of cancer have been generated in zebrafish. Owing to space constraints, we will focus exclusively on heritable tumor models in the zebrafish. These are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Table 1 lists all models according to cancer type and organ affected. The vast majority are transgenic lines expressing oncogenes driven by tissue-specific or ubiquitous promoters. Table 2 summarizes the genetic mutants that have provided evidence for the function of genes as tumor suppressors, and that were identified as TILLING (targeting induced local lesions in genomes) mutants or through forward genetic screens, and further investigated to show their mode of action. Excellent recent reviews describe all of these models in detail and list alternative approaches, such as the use of the zebrafish as a recipient for xenotransplantation of cancer cells, and the use of the zebrafish embryo to dissect the role of oncogenes and the biochemical signals that are activated in different cancer types (Amatruda and Patton, 2008; Feitsma and Cuppen, 2008; Stoletov and Klemke, 2008; Marques et al., 2009; Payne and Look, 2009; Taylor and Zon, 2009; Weiss et al., 2009). The bias in the choice of tissue-specific promoters used to generate the transgenic lines reflects the interest of the zebrafish labs that were engaged in the first generation of cancer models. The use of human oncogenes, often in conjunction with fluorescent reporters to aid the monitoring of tumor initiation and progression, and the isolation and in vivo imaging of cancer cells, demonstrated the cross-species ability of oncogenes to transform zebrafish cells.

Table 1.

Zebrafish cancer models

Table 2.

Cancer predisposition mutants

What is the utility of zebrafish cancer models?

To illustrate the advantages of the zebrafish cancer models, we provide examples of two groups of tumor models where the zebrafish has and will continue to provide important insights: melanoma and leukemia. Elegant studies on pancreatic adenocarcinoma (Park et al., 2008), sarcomas (Ju et al., 2009), intestinal hyperplasia (Haramis et al., 2006; Phelps et al., 2009) and other solid tumors have also been described in zebrafish; however, the space constraints of this article do not allow for a detailed discussion of these models here, but they are covered by some excellent recent reviews (Amatruda and Patton, 2008; Feitsma and Cuppen, 2008). The first fish melanoma model was reported in the 1920s in a closely related teleost, Xiphophorus maculatus. Hybrids between Xiphophorus maculatus and Xiphophorus hellerii developed melanoma when back-crossed. These hybrids carry the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor Xmrk and have lost a genetic modifier (known as R locus) that represses oncogenic Xmrk functions, leading to a high incidence of melanoma. These fish allowed for the investigation of anti-apoptotic and pro-proliferative pathways that are regulated by the oncogenic Xmrk (Meierjohann and Schartl, 2006), which is responsible for the disease manifestations. Recently, transgenesis was used to generate a strain of medaka carrying the Xmrk oncogene under the microphtalmia A (mitfa) promoter (Schartl et al., 2009).

Transgenic zebrafish melanoma models that use regulatory sequences of the mitfa gene to drive the expression of different oncogenes have been generated. In the Zon laboratory, the human oncogenes used were the frequently mutated BRAFV600E (Patton et al., 2005) and, more recently, mutant NRASQ61K (Dovey et al., 2009). Both mutations are found with a high frequency in human melanoma, suggesting that they may play a causative role. However, to develop melanoma, both strains also need to carry inactivating mutations in p53 (Berghmans et al., 2005).

Using the mitfa promoter, the Hurlstone lab generated a transgenic line expressing mutant HRAS in melanocytes (Michailidou et al., 2009). Development of melanoma in these zebrafish is rare, but can be accelerated easily by activating mutations in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway, thus confirming the role of this pathway in malignant transformation downstream of HRAS. The same oncogene was used by Santoriello (Anelli et al., 2009) to generate a double transgenic line that, subsequent to the expression of enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)-HRASV12 driven by the kita promoter in melanocyte precursors, develops melanoma in only 3–4 weeks and without the need for additional mutations in tumor suppressors. In addition, this line has a strong larval hyperpigmentation phenotype, thus representing an ideal background for large-scale chemical screens (see below). The mitfa promoter-driven mutant NRASQ61K melanoma model on the p53–/– background has also been used to derive a gene expression profile of melanoma cells in zebrafish (Dovey et al., 2009).

What aspects of these models could provide important information for the clinic?

First, the ability of oncogenes to induce melanoma seems to be correlated with the cells targeted by the different promoters (mitfa versus Xmrk or kita) rather than the oncogene itself. Second, the need for coinciding mutations in tumor suppressors that are already known in humans, but with a different range (p16 ARF rather than p53), suggests that tumor suppressors are interchangeable. Third, zebrafish models offer the possibility to harvest very well-defined stages of the disease. Fourth, the presence of a larval phenotype could provide a very valuable platform for high-throughput chemical screens. Finally, the use of ‘enhancer’ and ‘suppressor’ screens to detect new tumor suppressors or genetic modifiers that are important in melanoma development is also feasible.

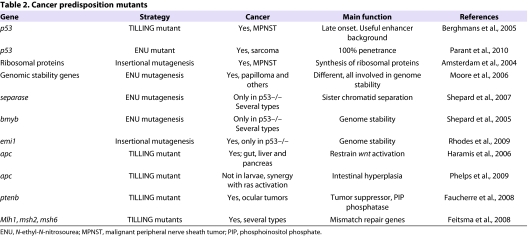

Most importantly, the transparent zebrafish provides a unique angle to evaluate host responses, not only to transplanted human tumor cells (Nicoli et al., 2007; Stoletov et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2009), but also to endogenous, oncogene-transformed cells; this provides unique opportunities to follow tumor angiogenesis and immune responses. An example of the power of the zebrafish for in vivo studies of immune responses to cancer cells arising at larval stages is shown in Fig. 1, where a group of GFP-labeled, oncogene-transformed cells is attacked by red fluorescent protein (RFP)-positive macrophages.

Fig. 1.

The use of a zebrafish melanoma model to detect immune responses. (A) A juvenile kita:GFP-HRASV12 zebrafish developing a melanocytic lesion on the tail fin. (B) The fish is also transgenic for LysC:RFP (Hall et al., 2007), which marks a subpopulation of macrophages. (C,D) Red macrophages attack and destroy a GFP-HRASV12 transformed cell. Bar, 100 μm (A); 40 μm (B); 10 μm (C,D).

Transplantation is a way of assessing the presence and number of melanoma-initiating cells, and the host responses (recruitment of vasculature, metastatic potential and immune responses). To this end, the generation of the completely transparent Casper mutant (White et al., 2008) has been particularly instrumental for the ease of visualizing transplanted melanoma cells in adult fish.

With the aim of exploiting the advantages that zebrafish offer, several groups have undertaken efforts to establish zebrafish models of leukemia (Kalev-Zylinska et al., 2002; Langenau et al., 2003; Sabaawy et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2007; Yeh et al., 2008; Frazer et al., 2009). The majority of these efforts have tagged malignant cells with GFP, making the detection and monitoring of disease straightforward. Pathologically, these leukemia models resemble their human counterparts very closely. Leukemic blasts infiltrate the bone marrow and all body tissues, are clonal, and have an altered DNA index (Langenau et al., 2003; Langenau et al., 2005; Sabaawy et al., 2006; Frazer et al., 2009).

In addition, blasts can be serially transplanted into zebrafish recipients, allowing for the analysis of leukemia-initiating cell number and high-risk genetic features (Frazer et al., 2009). The ease with which these transplantation experiments can be carried out and monitored by fluorescence microscopy is among the distinct advantages of these models.

The majority of zebrafish leukemia models rely on overexpression of proto-oncogenes that are misregulated in human leukemias; examples are c-Myc (Langenau et al., 2003), MOZ/TIF2 (Zhuravleva et al., 2008) and NOTCH1 (Chen et al., 2007), which all result in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL). In keeping with the ‘two-hit’ model in human leukemias (Gilliland, 2001), lymphoid malignancies in zebrafish also require additional hits for transformation. For example, in addition to the increased proliferative drive provided by c-Myc overexpression, the developing T-ALLs display deregulated tal1 and lmo2, adding differentiation arrest (Langenau et al., 2005). One downside of c-Myc overexpression is the rapid onset of disease that precludes the conduct of additional genetic studies. The Look lab has devised two strategies to circumvent this problem by creating heat shock- and Cre/lox-inducible c-Myc transgenic lines (Langenau et al., 2005; Feng et al., 2007).

Mutated genes in familial cancers can reveal molecular pathways that are deregulated in sporadic cases. Heritable leukemias in humans are rare, making it difficult to identify the underlying mutations. To address this problem genetically, Frazer et al. conducted a forward genetic strategy to establish heritable models of T-ALL (Frazer et al., 2009). Here, mutagenized F1 and gynogenetic F2 offspring from the T-cell-specific lck::EGFP transgenic line (Langenau et al., 2004) were screened for dominant and recessive disease manifestations. Offspring were screened after they had reached sexual maturity to ensure the propagation of the identified mutants with leukemic phenotypes. The confirmed dominant and recessive leukemias had similar penetrance to human cases and otherwise mimicked oncogene-driven zebrafish models of T-ALL. Using gene expression analysis, all five subtypes of T-ALL (Ferrando et al., 2002) were identified in individuals with heritable zebrafish leukemia (N.S.T. and J. Frazer, unpublished). Cloning of the underlying mutations promises to advance our understanding of leukemogenesis.

Efforts are also underway to identify cooperating proto-oncogenes and interacting tumor suppressors through enhancer and suppressor screens. The ease of inducing chemical mutations, and the large number of offspring that zebrafish can produce every week, make this model uniquely suited for such secondary screens.

Can we use zebrafish models to predict novel cancer markers?

Given the striking similarities between human and zebrafish tumors that have been reported in the literature (Amatruda et al., 2002), the zebrafish cancer models are particularly well suited to predict novel cancer markers, identify molecular prognostic signatures and to establish their role in disease progression. Most importantly, monitoring these markers in zebrafish models subjected to drug treatments, and then comparing the changes with the response of human tumor cells in isolation, will provide an important contribution to the development of targeted therapies. Prognostic markers associated with different tumor types were found to correlate with disease progression, and therefore to represent useful readouts not only for a correct stratification of patients, but also in the context of therapeutic choices. Most of the markers are causally involved in aspects of the disease, whereas others have unknown functions. The zebrafish with its basic biology toolbox will be instrumental in discovering the role of these markers in disease progression, in closely monitoring changes during different disease phases, and in developing charts that can be used in cross-species comparisons of tumor progression and response to drugs. Moreover, the overlap signature between humans and zebrafish promises to hit on conserved and important cancer pathways. The first comparisons between human and zebrafish cancer transcriptomes (Shepard et al., 2005; Lam et al., 2006; Langenau et al., 2007; Dovey et al., 2009; Ung et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2010) have proved very useful to establish the degree of conservation, and to discover new players in the zebrafish tumors that are now in the process of being validated in human samples. Clear signatures comprising a small number of genes whose changes identify, precisely, the type and grade of a cancer sample could help to standardize diagnosis and prognosis of tumors, and therefore be extremely useful in the clinics. A few examples of clear signatures have been derived for the most frequent and highly studied cancers (i.e. breast cancer); however, for less frequent and less homogenous cancer types, the signatures (when available) are composed of hundreds of genes, obscuring important markers and limiting their clinical usefulness (Bianchi et al., 2007). Genetic models that are defined precisely in terms of molecular landscape, stage and genetic background can reduce ‘genetic noise’. One advantage of zebrafish models is that large numbers of tumors – particularly for rare cancers – can be analyzed in relatively homogeneous populations. We think that it is now possible, and highly desirable, to use both mouse and zebrafish cancer models to generate reference transcriptomes associated with specific cancer models. Finding identical cancer signatures across species as different as the human, mouse and zebrafish will help us to understand the complexity of genetic cancer programs, and will be instrumental in defining biologically relevant signatures.

Another possible avenue to the identification of markers of tumor aggressiveness was suggested recently by serial transplantation assays of zebrafish T-ALL (Frazer et al., 2009; Ignatius and Langenau, 2009; Taylor and Zon, 2009; Smith et al., 2010) Here, iterative transplantations of EGFP-positive blasts into irradiated recipients led to a more rapid time to death. This finding can be explained either by a change in gene expression profile or by an increase in the proportion of leukemia initiating cells (LICs) with successive rounds of transplantation. Comparing patterns of gene expression, promoter methylation, and DNA amplifications or deletions, at the beginning and the end of iterative rounds of transplantation may reveal signatures that confer aggressive behavior of T-ALL. As a single operator can easily carry out dozens of transplantations in one day, large numbers of datasets will be available for comparison, allowing particularly important ‘aggressive’ signatures to emerge.

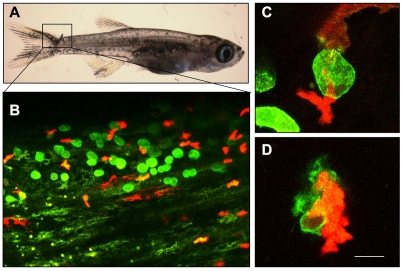

The construction of a ‘reference map’ of the transcriptome, proteome, and epigenome of specific tumors at different developmental stages, or in response to treatment, would be extremely valuable. In the clinical setting, information on gene expression in a given tumor is restricted to only one time point (following excision) or, at the most, to two time points (after relapse or following excision of the metastasis). The use of genetic models of cancer facilitates the assay of the cancer transcriptome at different stages and allows the construction of a reference map for precise stratification of cancer/patient status and therapeutic monitoring. The process is illustrated in Fig. 2, which summarizes the flow of information and can be applied to multiple samples and different data.

Fig. 2.

The generation of reference transcriptomes associated with specific cancer models. (A) Cross comparison between cancer transcriptomes of different stages within the same genetic model, further compared with different genetic models of the same tumor, will produce stage- and cancer-specific signatures. The transcriptome of each genetic model can be studied at precise stages (rectangles) and subjected to cross comparisons (Venn diagrams) to generate stage-specific signatures (the non-overlapping parts of the colored circles). This process can be repeated for any number of cancer models, even from different species. (B) These signatures will help to assign transcriptomes from unknown-stage human cancers to a specific class. In the left panels, the different shades of colored shapes identify stage-specific transcriptomes derived from animal models that, thanks to the large number examined, allow a single grade-specific signature (intensely-colored rectangles) to be derived. In the right panels, different transcriptomes from human cancer samples are assessed and assigned to a specific group. (C) A smaller number of ‘predictor genes’ can be derived from these cross-species comparisons, which can help to stratify patients to the correct cohort for prognosis and therapy follow-up.

Can we use zebrafish cancer models to identify new therapies?

As efforts intensify to develop targeted therapies for specific oncogene/signaling pathways, the zebrafish may provide a platform for testing and refining these therapies in the preclinical phase of drug development. Conventionally, cell culture or biochemical assays have been employed to assess the biologic effect of chemical compounds. Although, at times, highly successful in identifying new treatments (Druker et al., 2001), the vast efforts by pharmaceutical companies using this approach have not been met with commensurate success. Among the reasons for this is the frequent difficulty to translate test tube success into an in vivo system, where a drug has to be absorbed through epithelial barriers, is exposed to metabolizing enzymes, and then has to find its target. One option to obviate many of these caveats is to assess the effect of a drug on the organismal level at the screening stage. Here, the small size of zebrafish and their suitability for the direct readout of biologic processes offer new opportunities.

For example, assessing the response to treatment of leukemic blasts in adult zebrafish with EGFP-positive T-ALL is straightforward by fluorescence microscopy. Adding dexamethasone to fish water potently induces tumor lysis and the complete remission of affected individuals within several days of treatment (J. Frazer, N. Meeker and N.S.T., unpublished). This opens the door for preclinical testing of anti-T-ALL drugs in an entire vertebrate organism. Although adult fish are not suitable for high-throughput in vivo drug screening, zebrafish embryos are uniquely suited for this purpose (Kaufman et al., 2009). Of the currently available zebrafish tumor models, only two manifest in the embryonic to larval stage so that high-throughput screening in 96-well plates is feasible. The first is a heat shock-inducible AML1-ETO transgenic line that develops an acute myeloid leukemia (AML)-like phenotype at 2 days post-fertilization (Yeh et al., 2008). By screening the 2000 known bioactive compounds from the Spectrum library (Microsource Discovery Systems), unexpected roles for cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2)- and β-catenin-dependent pathways were uncovered that impinge on AML1-ETO function (Yeh et al., 2009). The second model is Ras-induced melanoma that manifests in the larval stages as melanotic expansion of pigment cells, making this model amenable to small molecule screens (Anelli et al., 2009).

Conclusions

The zebrafish is uniquely suited to contribute novel insights in cancer biology and provide a ‘whole-organism test tube’ for the rapid identification of cancer markers, the assessment of their functions, the study of host responses, and the development of anti-cancer drugs.

Advantages of the zebrafish as a model for cancer.

Zebrafish are amenable to genetic manipulation. Forward genetics shows their utility in predicting novel cancer markers. Cancer models have been created by both spontaneous mutation and transgenetics that recapitulate mutations found in human cancers

The transparent body of the zebrafish is conducive to long-term evaluation of cancer cells and the environmental response to them, including angiogenesis and inflammation. Cancer cells can be marked and transplanted into the zebrafish

Zebrafish are small and easy to house, and embryos are useful for pharmacological screening

Zebrafish models of leukemia were created through overexpression of proto-oncogenes that are misregulated in human disease

Acknowledgments

Work in the laboratories of the authors is supported by AIRC (Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro) and Cariplo Foundation (grant no. 2007–5500) for M.C.M., and by R21AI079784-01, NICHD and the Huntsman Cancer Institute/Foundation, and the Department of Oncological Sciences for N.S.T. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Amatruda JF, Patton EE. (2008). Genetic models of cancer in zebrafish. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 271, 1–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amatruda JF, Shepard JL, Stern HM, Zon LI. (2002). Zebrafish as a cancer model system. Cancer Cell 1, 229–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsterdam A, Sadler KC, Lai K, Farrington S, Bronson RT, Lees JA, Hopkins N. (2004). Many ribosomal protein genes are cancer genes in zebrafish. PLoS Biol. 2, E139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anelli V, Santoriello C, Distel M, Ciccarelli F, Koster R, Mione M. (2009). Global repression of cancer gene expression in a zebrafish model of melanoma is linked to epigenetic regulation. Zebrafish 6, 417–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghmans S, Murphey RD, Wienholds E, Neuberg D, Kutok JL, Fletcher CD, Morris JP, Liu TX, Schulte-Merker S, Kanki JP, et al. (2005). tp53 mutant zebrafish develop malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 407–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi F, Nuciforo P, Vecchi M, Bernard L, Tizzoni L, Marchetti A, Buttitta F, Felicioni L, Nicassio F, Di Fiore PP. (2007). Survival prediction of stage I lung adenocarcinomas by expression of 10 genes. J Clin Invest. 117, 3436–3444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Jette C, Kanki JP, Aster JC, Look AT, Griffin JD. (2007). NOTCH1-induced T-cell leukemia in transgenic zebrafish. Leukemia 21, 462–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovey M, White RM, Zon LI. (2009). Oncogenic NRAS cooperates with p53 loss to generate melanoma in zebrafish. Zebrafish 6, 397–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, Peng B, Buchdunger E, Ford JM, Lydon NB, Kantarjian H, Capdeville R, Ohno-Jones S, et al. (2001). Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. New Engl J Med. 344, 1031–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faucherre A, Taylor GS, Overvoorde J, Dixon JE, Hertog J. (2008). Zebrafish pten genes have overlapping and non-redundant functions in tumorigenesis and embryonic development. Oncogene 27, 1079–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feitsma H, Cuppen E. (2008). Zebrafish as a cancer model. Mol Cancer Res. 6, 685–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feitsma H, Kuiper RV, Korving J, Nijman IJ, Cuppen E. (2008). Zebrafish with mutations in mismatch repair genes develop neurofibromas and other tumors. Cancer Res. 68, 5059–5066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H, Langenau DM, Madge JA, Quinkertz A, Gutierrez A, Neuberg DS, Kanki JP, Look AT. (2007). Heat-shock induction of T-cell lymphoma/leukaemia in conditional Cre/lox-regulated transgenic zebrafish. Br J Haematol. 138, 169–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando AA, Neuberg DS, Staunton J, Loh ML, Huard C, Raimondi SC, Behm FG, Pui CH, Downing JR, Gilliland DG, et al. (2002). Gene expression signatures define novel oncogenic pathways in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell 1, 75–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer JK, Meeker ND, Rudner L, Bradley DF, Smith AC, Demarest B, Joshi D, Locke EE, Hutchinson SA, Tripp S, et al. (2009). Heritable T-cell malignancy models established in a zebrafish phenotypic screen. Leukemia 23, 1825–1835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliland DG. (2001). Hematologic malignancies. Curr Opin Hematol. 8, 189–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C, Flores MV, Storm T, Crosier K, Crosier P. (2007). The zebrafish lysozyme C promoter drives myeloid-specific expression in transgenic fish. BMC Dev Biol. 4, 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haramis AP, Hurlstone A, van der Velden Y, Begthel H, van den Born M, Offerhaus GJ, Clevers HC. (2006). Adenomatous polyposis coli-deficient zebrafish are susceptible to digestive tract neoplasia. EMBO Rep. 7, 444–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatius MS, Langenau DM. (2009). Zebrafish as a model for cancer self-renewal. Zebrafish 6, 377–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju B, Spitsbergen J, Eden CJ, Taylor MR, Chen W. (2009). Co-activation of hedgehog and AKT pathways promote tumorigenesis in zebrafish. Mol Cancer 8, 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalev-Zylinska ML, Horsfield JA, Flores MV, Postlethwait JH, Vitas MR, Baas AM, Crosier PS, Crosier KE. (2002). Runx1 is required for zebrafish blood and vessel development and expression of a human RUNX1-CBF2T1 transgene advances a model for studies of leukemogenesis. Development 129, 2015–2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman CK, White RM, Zon L. (2009). Chemical genetic screening in the zebrafish embryo. Nat Protoc. 4, 1422–1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam SH, Wu YL, Vega VB, Miller LD, Spitsbergen J, Tong Y, Zhan H, Govindarajan KR, Lee S, Mathavan S, et al. (2006). Conservation of gene expression signatures between zebrafish and human liver tumors and tumor progression. Nat Biotechnol. 24, 73–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenau DM, Traver D, Ferrando AA, Kutok JL, Aster JC, Kanki JP, Lin S, Prochownik E, Trede NS, Zon LI, et al. (2003). Myc-induced T cell leukemia in transgenic zebrafish. Science 299, 887–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenau DM, Ferrando AA, Traver D, Kutok JL, Hezel JP, Kanki JP, Zon LI, Look AT, Trede NS. (2004). In vivo tracking of T cell development, ablation, and engraftment in transgenic zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 7369–7374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenau DM, Feng H, Berghmans S, Kanki JP, Kutok JL, Look AT. (2005). Cre/lox-regulated transgenic zebrafish model with conditional myc-induced T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 6068–6073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenau DM, Keefe MD, Storer NY, Guyon JR, Kutok JL, Le X, Goessling W, Neuberg DS, Kunkel LM, Zon LI. (2007). Effects of RAS on the genesis of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Genes Dev. 21, 1382–1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le X, Langenau DM, Keefe MD, Kutok JL, Neuberg DS, Zon LI. (2007). Heat shock-inducible Cre/Lox approaches to induce diverse types of tumors and hyperplasia in transgenic zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 9410–9415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SL, Rouhi P, Dahl Jensen L, Zhang D, Ji H, Hauptmann G, Ingham P, Cao Y. (2009). Hypoxia-induced pathological angiogenesis mediates tumor cell dissemination, invasion, and metastasis in a zebrafish tumor model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 19485–19490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques IJ, Weiss FU, Vlecken DH, Nitsche C, Bakkers J, Lagendijk AK, Partecke LI, Heidecke CD, Lerch MM, Bagowski CP. (2009). Metastatic behaviour of primary human tumours in a zebrafish xenotransplantation model. BMC Cancer 9, 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meierjohann S, Schartl M. (2006). From Mendelian to molecular genetics: the Xiphophorus melanoma model. Trends Genet. 22, 654–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michailidou C, Jones M, Walker P, Kamarashev J, Kelly A, Hurlstone AF. (2009). Dissecting the roles of Raf- and PI3K-signalling pathways in melanoma formation and progression in a zebrafish model. Dis Model Mech. 2, 399–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JL, Rush LM, Breneman C, Mohideen MA, Cheng KC. (2006). Zebrafish genomic instability mutants and cancer susceptibility. Genetics 174, 585–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann JC, Dovey JS, Chandler GL, Carbajal L, Amatruda JF. (2009). Identification of a heritable model of testicular germ cell tumor in the zebrafish. Zebrafish 6, 319–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoli S, Ribatti D, Cotelli F, Presta M. (2007). Mammalian tumor xenografts induce neovascularization in zebrafish embryos. Cancer Res. 67, 2927–2931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onnebo SM, Condron MM, McPhee DO, Lieschke GJ, Ward AC. (2005). Hematopoietic perturbation in zebrafish expressing a tel-jak2a fusion. Exp Hematol. 33, 182–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parant JM, George SA, Holden JA, Yost HJ. (2010). Genetic modeling of Li-Fraumeni syndrome in zebrafish. Dis Model Mech. 3, 45–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SW, Davison JM, Rhee J, Hruban RH, Maitra A, Leach SD. (2008). Oncogenic KRAS induces progenitor cell expansion and malignant transformation in zebrafish exocrine pancreas. Gastroenterology 134, 2080–2090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton EE, Widlund HR, Kutok JL, Kopani KR, Amatruda JF, Murphey RD, Berghmans S, Mayhall EA, Traver D, Fletcher CD, et al. (2005). BRAF mutations are sufficient to promote nevi formation and cooperate with p53 in the genesis of melanoma. Curr Biol. 15, 249–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne E, Look T. (2009). Zebrafish modelling of leukaemias. Br J Haematol. 146, 247–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps RA, Chidester S, Dehghanizadeh S, Phelps J, Sandoval IT, Rai K, Broadbent T, Sarkar S, Burt RW, Jones DA. (2009). A two-step model for colon adenoma initiation and progression caused by APC loss. Cell 137, 623–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes J, Amsterdam A, Sanda T, Moreau LA, McKenna K, Heinrichs S, Ganem NJ, Ho KW, Neuberg DS, Johnston A, et al. (2009). Emi1 maintains genomic integrity during zebrafish embryogenesis and cooperates with p53 in tumor suppression. Mol Cell Biol. 29, 5911–5922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabaawy HE, Azuma M, Embree LJ, Tsai HJ, Starost MF, Hickstein DD. (2006). TEL-AML1 transgenic zebrafish model of precursor B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 15166–15171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoriello C, Deflorian G, Pezzimenti F, Kawakami K, Lanfrancone L, d’Adda di Fagagna F, Mione M. (2009). Expression of H-RASV12 in a zebrafish model of Costello syndrome causes cellular senescence in adult proliferating cells. Dis Model Mech. 2, 56–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schartl M, Wilde B, Laisney JA, Taniguchi Y, Takeda S, Meierjohann S. (2009). A mutated EGFR is sufficient to induce malignant melanoma with genetic background-dependent histopathologies. J Invest Dermatol. 130, 249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard JL, Amatruda JF, Stern HM, Subramanian A, Finkelstein D, Ziai J, Finley KR, Pfaff KL, Hersey C, Zhou Y, et al. (2005). A zebrafish bmyb mutation causes genome instability and increased cancer susceptibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 13194–13199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard JL, Amatruda JF, Finkelstein D, Ziai J, Finley KR, Stern HM, Chiang K, Hersey C, Barut B, Freeman JL, et al. (2007). A mutation in separase causes genome instability and increased susceptibility to epithelial cancer. Genes Dev. 21, 55–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AC, Raimondi AR, Salthouse CD, Ignatius MS, Blackburn JS, Mizgirev IV, Storer NY, de Jong JL, Chen AT, Zhou Y, et al. (2010). High-throughput cell transplantation establishes that tumor-initiating cells are abundant in zebrafish T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. Jan 7 [Epub ahead of print] [doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-246488]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stoletov K, Klemke R. (2008). Catch of the day: zebrafish as a human cancer model. Oncogene 27, 4509–4520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoletov K, Montel V, Lester RD, Gonias SL, Klemke R. (2007). High-resolution imaging of the dynamic tumor cell vascular interface in transparent zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 17406–17411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AM, Zon LI. (2009). Zebrafish tumor assays: the state of transplantation. Zebrafish 6, 339–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ung CY, Lam SH, Gong Z. (2009). Comparative transcriptome analyses revealed conserved biological and transcription factor target modules between the zebrafish and human tumors. Zebrafish 6, 425–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss FU, Marques IJ, Woltering JM, Vlecken DH, Aghdassi A, Partecke LI, Heidecke CD, Lerch MM, Bagowski CP. (2009). Retinoic acid receptor antagonists inhibit miR-10a expression and block metastatic behavior of pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology 137, 2136–2145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RM, Sessa A, Burke C, Bowman T, LeBlanc J, Ceol C, Bourque C, Dovey M, Goessling W, Burns CE, et al. (2008). Transparent adult zebrafish as a tool for in vivo transplantation analysis. Cell Stem Cell 2, 183–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HW, Kutok JL, Lee NH, Piao HY, Fletcher CD, Kanki JP, Look AT. (2004). Targeted expression of human MYCN selectively causes pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in transgenic zebrafish. Cancer Res. 64, 7256–7262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh JR, Munson KM, Chao YL, Peterson QP, Macrae CA, Peterson RT. (2008). AML1-ETO reprograms hematopoietic cell fate by downregulating scl expression. Development 135, 401–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh JR, Munson KM, Elagib KE, Goldfarb AN, Sweetser DA, Peterson RT. (2009). Discovering chemical modifiers of oncogene-regulated hematopoietic differentiation. Nat Chem Biol. 5, 236–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuravleva J, Paggetti J, Martin L, Hammann A, Solary E, Bastie JN, Delva L. (2008). MOZ/TIF2-induced acute myeloid leukaemia in transgenic fish. Br J Haematol. 143, 378–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]