There is a smoking room in Zhang Pei Pei’s office in Beijing, China.

At any time of the day, men crowd the small space, lighting up and puffing away until they’re enveloped in a thick, cloudy haze.

But when Zhang has a craving for one of 10 cigarettes she’ll smoke each day, she doesn’t join her male colleagues. “There’s not one woman in there,” she says. “If I went in there, the men might not be too happy.”

Instead, she treks outside to light up, and if she looks left or right, will typically see other women doing the same.

It is becoming an increasingly common sight in China.

In a country of 350 million smokers, more than 60% of men, and 4% of women, are smokers.

But the latter percentage is set to rise, say experts at the World Health Organization. They estimate that 20% of women worldwide will be smokers by 2025, as compared with the 12% who smoke today.

Chinese health experts say the trend is exacerbated in China because of the country’s new affluence, which has brought about rapid economic, social and cultural change, particularly in cities and booming coastal regions.

But there’s been a simultaneous public health toll in terms of soaring incidence in obesity, diabetes, hypertension, lung and breast cancer, and cardiovascular disease rates. The Chinese are consuming more fat, more sugar and more salt.

And more tobacco.

China is already the world’s biggest consumer and producer of cigarettes, manufacturing 2.2 trillion smokes every year.

But women have traditionally shied away from smoking, largely because of cultural taboos.

No more.

“Women are becoming more independent. They’ve got more money. They listen less to their parents and teachers,” says Dr. Judith Mackay, a senior WHO policy advisor who has led antismoking campaigns across Asia. “It’s the right culture for the introduction of thinking wrongly, thinking that smoking is associated with emancipation. We have to make them realize it’s addictive. It is a [form of] bondage.”

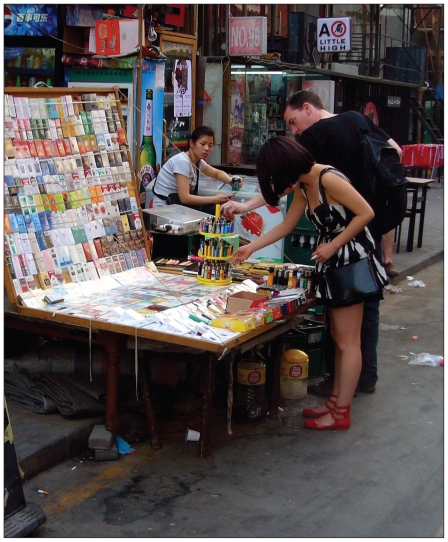

A female smoker browses a wide array of cigarettes and lighters on sale on a Beijing street.

In a bid to tap the female market, tobacco companies have started using colourful packaging, while marketing long, slender and flavoured cigarettes labelled “low-tar” or “light.”

To the chagrin of her parents, Zhang began smoking five years ago because she was curious and indulging in a quasi-taboo activity seemed fun and exciting.

Menthol-flavoured cigarettes helped clear her mind and smoking quickly grew into a daily habit as a result of stresses at her job in the information technology industry.

“I started pulling a lot of overtime,” she says. “Smoking is a way for me to vent. It’s like all the pressure comes out of me, along with the smoke. It’s a great feeling of freedom to know I can do this.”

According to the tobacco control office of China’s Centre for Disease Control, that feeling of freedom is costly: more than one million Chinese people die annually from tobacco-related illnesses, about one-quarter of all smoking-related deaths worldwide. By 2020, the WHO estimates that toll could climb to three million.

“You can look at swine flu or SARS, but it’s clear nothing kills like tobacco does,” Mackay says. “It’s not like a mine collapse or a road accident where people are killed immediately and there’s a national response to it. This is a long-term disease and there should be a national response to this, too.”

The Chinese government is taking tentative steps. It has banned tobacco advertising on television and radio (but not billboards), while adding health warnings to cigarette packaging. Smoking was prohibited at the 2008 Summer Olympics and at the World Expo in Shanghai. More than 200 million reminbi (roughly $30 million) worth of Expo-related donations from tobacco companies were returned after the nongovernmental Chinese Association on Tobacco Control pressed for the organizing committee to honour its promise of hosting a “smoke-free” event.

China was a signatory to the 2003 UN Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, which obliges it to ban all tobacco advertising and smoking in all public places, while raising tobacco taxes, before January 2011.

But few believe those goals will be realized, including government officials.

“There’s a very long road ahead of us,” says Jiang Yuan, vice-director of the Centre for Disease Control’s tobacco control office. He adds that regulations banning smoking in indoor public spaces have only been adopted in seven provincial capitals.

There’s no way a prohibition will be achieved by 2011, adds Xu Guihua, vice-president of the Chinese Association on Tobacco Control. “This goal needs related national laws and regulations. The result of China’s tobacco control and its progress highly depends on the Chinese government’s attitude and determination.”

That attitude may be predicated on a conflict-of-interest: China’s largest tobacco company is state-owned. Critics say that has prevented the government from raising prices. A 2009 tax increase was modest and absorbed entirely by the industry. A package of cigarettes now retails for as little as $1.50 in Beijing and Shanghai.

Nonsmoking campaigns appear the government’s preferred option, including a special appeal to women made during the release of the China Center for Disease Control’s annual tobacco report, which warned of the increased danger of developing tobacco-related illnesses and appealed to a woman’s cosmetic sense by asserting that smoking will bring on early signs of aging and damage the skin and teeth.

The report also cited data linking smoking to low fertility rates, miscarriages and infant deformities, noting that a survey of 1300 families indicated that 47.9% of pregnant women are exposed to second-hand smoke.

Those kinds of nonsmoking pitches may eventually sway 30-year-old Zhang, who hopes to one day have a child. “But that time hasn’t come yet,” she says. “I want a healthy baby. So when it’s time, I will quit smoking for the child. It might not be easy, but it’s an important enough reason to try.”