Abstract

Prior research indicates that reinforcement of an appropriate response (e.g., compliance) can produce concomitant reductions in problem behavior reinforced by escape when problem behavior continues to produce negative reinforcement (e.g., Lalli et al., 1999). These effects may be due to a preference for positive over negative reinforcement or to positive reinforcement acting as an abolishing operation, rendering demands less aversive and escape from demands less effective as negative reinforcement. In the current investigation, we delivered a preferred food item and praise on a variable-time 15-s schedule while providing escape for problem behavior on a fixed-ratio 1 schedule in a demand condition for 3 participants with problem behavior maintained by negative reinforcement. Results for all 3 participants showed that variable-time delivery of preferred edible items reduced problem behavior even though escape continued to be available for these responses. These findings are discussed in the context of motivating operations.

Keywords: Asperger syndrome, autism, functional analysis, motivating operations, negative reinforcement, noncontingent reinforcement, response-independent reinforcement, time-based schedules

Current methods of treating problem behavior typically begin with a functional analysis that is used to identify the reinforcers for the target response (e.g., Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, & Richman, 1982/1994), and the identified reinforcer is manipulated in ways that reduce the probability of the problem behavior (e.g., Hanley, Piazza, Fisher, & Maglieri, 2005; Iwata, Pace, Cowdery, & Miltenberger, 1994; Piazza et al., 1998). For example, when the results of a functional analysis indicate that problem behavior is reinforced by escape (i.e., negative reinforcement), a potentially effective intervention is to eliminate the escape contingency and continue to present demands independent of problem behavior, a treatment referred to as escape extinction (Iwata, Pace, Kalsher, Cowdery, & Cataldo, 1990). Although escape extinction has typically been found to be an effective treatment for problem behavior maintained by escape, it sometimes produces untoward effects (e.g., extinction bursts; Goh & Iwata, 1994; Lerman & Iwata, 1996; Piazza, Patel, Gulotta, Sevin, & Layer, 2003).

Several treatments have been developed as adjuncts to extinction in order to mitigate its negative side effects, such as (a) differential negative reinforcement of alternative behavior (DNRA; Marcus & Vollmer, 1995), (b) differential positive reinforcement of alternative behavior (DPRA; Patel, Piazza, Martinez, Volkert, & Santana, 2002), (c) time-based delivery of preferred stimuli (Fisher, DeLeon, Rodriguez-Catter, & Keeney, 2004) or escape (Vollmer, Marcus, & Ringdahl, 1995), and (d) stimulus (or demand) fading (Pace, Ivancic, & Jefferson, 1994). However, even when these adjunct procedures are combined with extinction, extinction bursts may still occur (cf. Lerman & Iwata, 1996). In addition, escape extinction often involves physically guiding the individual to complete the nonpreferred task, which can be difficult or even impossible if the client is stronger than the therapist or parent or if the response cannot be physically guided (e.g., spoken answers to academic problems). In such cases, alternative interventions are needed that do not involve escape extinction.

One recently evaluated approach for treating problem behavior maintained by escape that has been implemented without escape extinction involves differential positive reinforcement of alternative behavior (DPRA can be implemented with or without escape extinction) such that potent positive reinforcers are in direct competition with the escape contingency for problem behavior (Adelinis, Piazza, & Goh, 2001; DeLeon, Neidert, Anders, & Rodriguez-Catter, 2001; Fisher et al., 2005; Lalli, Casey, & Kates, 1995; Lalli et al., 1999; Piazza et al., 1997). For example, Lalli et al. (1999) treated five individuals who displayed escape-reinforced problem behavior using DPRA. The treatment consisted of the delivery of preferred food items contingent on compliance on a fixed-ratio (FR) 1 schedule while problem behavior continued to produce escape from demands on a concurrent FR 1 schedule. In each of the five cases, problem behavior decreased to low levels even though it continued to produce escape.

Lalli et al. (1999) explained the beneficial effects of this intervention in terms of differences in reinforcer quality in which problem behavior and compliance were concurrent operants with qualitatively different reinforcers. According to this interpretation, the participants generally preferred food to escape and displayed the operant response (compliance) that produced food much more often than the operant response that produced escape (problem behavior). Lalli et al. also acknowledged the possibility that the delivery of a preferred food item in the demand context via DPRA may have acted as a motivating operation (more specifically, an abolishing operation; Laraway, Snycerski, Michael, & Poling, 2003), rendering demands less aversive and escape from demands less effective as negative reinforcement. The results of two recent reports suggest that this latter explanation is a reasonable one (Gardner, Wacker, & Boelter, 2009; Ingvarsson, Kahng, & Hausman, 2008).

The purpose of the current study was to provide a more direct test of whether the delivery of positive reinforcers during demands acts as an abolishing operation and lowers the effectiveness of escape as negative reinforcement for problem behavior. Specifically, we assessed the extent to which the delivery of praise and preferred food items on a variable-time (VT) schedule would reduce three children's problem behavior maintained by escape.

METHOD

Participants and Setting

Participants were three boys who had been admitted to an intensive day-treatment program for the assessment and treatment of problem behavior. Sam was 8 years old and had been diagnosed with Asperger syndrome and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. He had been admitted for the assessment and treatment of aggression and destructive behaviors. He displayed mild developmental delays and had been mainstreamed in a regular education classroom prior to his admission. Aaron was 8 years old and had been diagnosed with autism. He had been admitted for the assessment and treatment of aggression, destructive behavior, and yelling. Mark was 9 years old and had been diagnosed with autism. He had been admitted for the assessment and treatment of aggression, destructive behavior, and self-injurious behaviors (SIB).

All sessions were conducted in a padded room that contained chairs, tables, and other materials relevant to the condition in effect (see session description below). Each room was equipped with a one-way observation window that allowed unobtrusive observation of the sessions. All sessions were either 10 min (Sam) or 5 min (Aaron and Mark) in length. A therapist was present in the room during all conditions.

Response Measurement and Interobserver Agreement

During all sessions, trained observers used laptop computers to record each target response (problem behavior, rate of demands, compliance). Problem behavior included aggression and destructive behavior for all participants, with the addition of yelling for Aaron and SIB for Mark. Operational definitions were identical for all participants for aggression (defined as hitting, punching, slapping, pinching, scratching, pulling hair, biting, throwing objects at the therapist) and destructive behavior (defined as throwing objects at people; knocking over furniture, materials, or objects; and tearing materials). For Aaron, yelling was defined as any word or nonword vocalization above conversational level that lasted less than 3 s. For Mark, SIB was defined as self-biting, self-pinching, and self-scratching. Free-operant target responses (aggression, property destruction, SIB) were converted to rate measures by dividing the number of responses in a session by the number of minutes in the session. Compliance was converted to a percentage measure after dividing the frequency of compliance by the frequency of demands presented in a session.

To measure procedural integrity, observers recorded the delivery of each demand during both the baseline and VT phases for all children. For Sam, they also recorded each delivery of food and praise during the VT phases.

For the purpose of determining interobserver agreement, a second observer simultaneously but independently observed 26% of functional analysis sessions and 42% of treatment assessment sessions. These sessions were partitioned into successive 10-s intervals for the purpose of calculating agreement coefficients. An exact agreement was scored in an interval if both observers recorded the same number of target responses. Coefficients were calculated by dividing the number of exact agreements by the total number of intervals in a session and then converting the quotient to a percentage. Mean interobserver agreement for problem behavior in the functional analysis was 98% (range, 95% to 99%). Mean interobserver agreement coefficients for problem behavior, rate of demands, and compliance were 96% (range, 95% to 98%), 74% (range, 56% to 84%), and 87% (range, 80% to 92%), respectively. The agreement coefficients for demand issuance were low because the observers had to monitor the session clock, signal the therapist when the VT schedule elapsed, and record both participant and therapist behavior simultaneously.

Experimental Design

A multielement design was used for the functional analysis, and a reversal design (ABAB) was used during the treatment analysis (A was baseline and B was treatment, which consisted of delivery of a preferred item on a VT 15-s schedule).

Procedure

Functional analysis

Each child was exposed to a functional analysis based on the procedures described by Iwata et al. (1982/1994) with modifications similar to those made by Fisher, Piazza, and Chiang (1996), except that reinforcement intervals lasted 20 s (rather than 30 s) and a tangible condition was included. Prior to the functional analysis, preferred items were identified for Sam and Aaron via a preference assessment, as described by Fisher et al. (1992). For Sam, a CD player was identified as the most preferred item, and a small toy car was identified for Aaron. For Mark, different tangible items were identified prior to each session using the procedures described by DeLeon and Iwata (1996); no food items were included in his assessments. Prior to the tangible condition sessions, the most highly preferred item identified during the preference assessment was available freely for approximately 2 min. When the tangible session began, the item was withdrawn and returned to the participant for 20 s contingent on each occurrence of problem behavior. An abbreviated functional analysis was conducted with Mark in which only the tangible and demand conditions were conducted; this decision was based in part on descriptive data that suggested that his problem behavior was reinforced by escape. The tangible condition was used as the control condition (rather than toy play) because it established positive reinforcement (deprivation of tangible items and attention) and abolished negative reinforcement through the absence of demands. Consistently low levels of problem behavior in this condition combined with consistently higher rates in the demand condition suggested that escape was the primary (if not sole) reinforcer for problem behavior for Mark.

Treatment analysis

Baseline sessions were identical to the demand condition of the functional analysis. During the demand condition, the therapist presented sequential verbal, gestural, and physical prompts every 10 s within each trial until the participant completed the task or problem behavior occurred. The therapist initiated each trial once the participant completed the previous task, unless problem behavior occurred. Contingent on the occurrence of problem behavior, all prompting ceased for 20 s. During treatment, sessions were identical to baseline sessions, with the following exception. The therapist delivered a small, highly preferred edible item and praise in the form of comments not related to the demand (e.g., “You're a cool kid”) on a VT 15-s schedule. The food item was identified prior to each session using procedures similar to those described by DeLeon and Iwata (1996), except that only a single trial was completed before each session to identify the highly preferred food. It should be noted that the preferred stimulus delivered during the VT schedule was different from the preferred nonfood item that the therapist delivered contingent on problem behavior in the tangible condition of the functional analysis.

The VT 15-s schedule included any number between 10 s and 20 s, with the mean equal to 15 s. Each interval length was equally probable (random selection with replacement). An observer monitored the session clock and the VT clock and signaled to the therapist when the VT schedule elapsed by tapping the observation window; the therapist then immediately delivered the food and praise. A VT schedule was used rather than an FT schedule to decrease the chances of adventitious reinforcement in which compliance with demands was followed closely by delivery of the food item and attention. We chose a dense schedule (i.e., reinforcement about every 15 s) because prior research has shown that dense schedules of noncontingent reinforcement tend to produce greater reductions in problem behavior than lean schedules (e.g., Hagopian, Fisher, & Legacy, 1994).

RESULTS

Functional Analysis

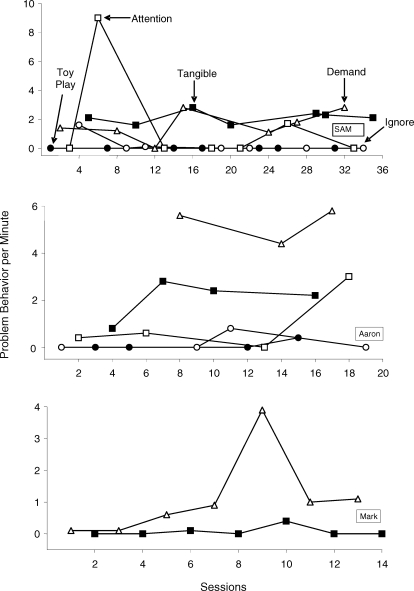

Sam engaged in consistently elevated rates of problem behavior only in the demand (M = 1.6 responses per minute) and tangible (M = 2.1) conditions relative to the play condition (M = 0; Figure 1). These results indicated that Sam's problem behavior was maintained by both access to tangible items and escape from demands. Similar results were observed with Aaron.

Figure 1.

Rates of problem behavior during the test and control conditions of the functional analyses.

For Mark, a pairwise analysis (Iwata, Duncan, Zarcone, Lerman, & Shore, 1994) showed elevated rates of problem behavior in the demand condition (M = 1.1 responses per minute) and low levels of problem behavior in the tangible condition (M = 0.1). These results suggested that Mark's problem behavior was reinforced by escape.

Treatment Analysis

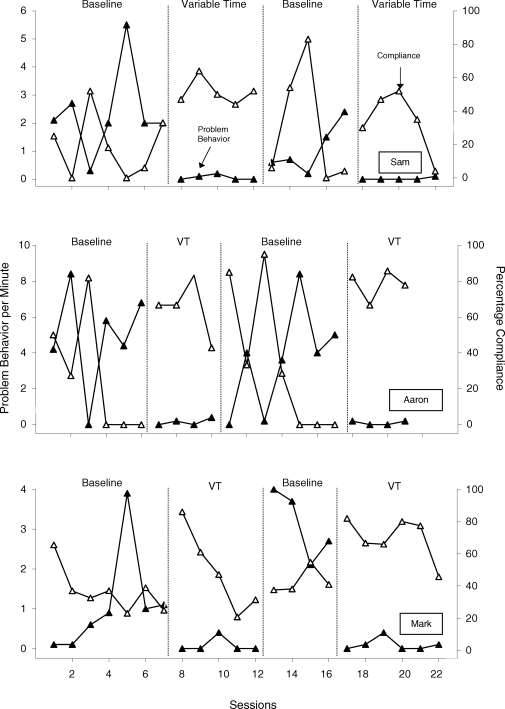

For Sam (Figure 2), problem behavior occurred at high levels (M = 2.4 responses per minute) during the first baseline phase. Problem behavior decreased to near-zero levels (M = 0.1) in the initial phase of the VT schedule, despite the availability of escape contingent on problem behavior. During the second baseline phase, levels of problem behavior were low initially but increased towards the end of the phase (M = 1.1). The effects of the VT schedule were replicated in the final phase. Similar reductive effects of VT food and praise were observed with Aaron and Mark (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Rates of problem behavior and percentages of compliance during the baseline and VT food and praise conditions of the treatment analysis.

We also evaluated the effects of VT food and praise on compliance (Figure 2). Levels of compliance were only slightly higher during treatment with VT food and praise for Sam (Ms for baseline and treatment = 23% and 39%, respectively) and Mark (Ms for baseline and treatment = 39% and 60%, respectively). However, Aaron's compliance was maintained at higher and more stable levels during VT food and praise (Ms for baseline and treatment = 31% and 71%, respectively).

We also monitored the rate at which demands were delivered during the baseline and treatment phases to ensure that reductions in problem behavior were not attributable to a change in the rate of demands (i.e., the delivery of food on a VT schedule could have lowered the rate of demands inadvertently). The rate of demand delivery was slightly higher during treatment with VT food and praise than during baseline for all three participants (Ms = 2.1 and 2.5 for Sam, 2.4 and 2.6 for Aaron, and 3.0 and 3.9 for Mark during baseline and treatment, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The three participants displayed problem behavior that was maintained at least in part by escape from demands. Variable-time delivery of food and praise superimposed on a demand baseline (in which problem behavior continued to produce escape) greatly reduced problem behavior for all three children and increased compliance for one child. These results support the findings of both Piazza et al. (1997) and Lalli et al. (1999) that delivery of positive reinforcers in a demand context can be an effective treatment for individuals whose problem behavior is maintained by negative reinforcement.

Our study also extends prior research in this area by identifying one operant mechanism responsible for reductions in escape-reinforced problem behavior that results from the delivery of highly preferred items in the demand context. Lalli et al. (1999) hypothesized that compliance and destructive behavior were concurrent operants, and differences in the quality of the reinforcers associated with the two responses biased responding toward compliance. In this investigation, we tested an alternative hypothesis, namely that the delivery of food contingent on compliance may lessen the aversiveness of demands and lower motivation for escape (i.e., food may act as an abolishing operation and lower the effectiveness of escape as negative reinforcement for problem behavior). The current study provides strong support for this alternative hypothesis because the therapist delivered food on a time-based schedule, and escape was available throughout all phases of the treatment evaluation. That is, escape was available for problem behavior both during baseline and during treatment, yet children rarely accessed escape when the therapist delivered food on a VT schedule during treatment. These results show that the delivery of a highly preferred food probably acted as a motivating operation (Laraway et al., 2003) and more specifically as an abolishing operation that lowered the participant's motivation to emit problem behavior reinforced by escape.

Smith, Iwata, Goh, and Shore (1995) proposed a method for evaluating the establishing (or abolishing) effects of antecedent stimuli in which the relevant antecedent is introduced and withdrawn while the consequences for the target response are held constant. That is, if a reinforcement contingency remains constant while the introduction and withdrawal of an antecedent intervention are correlated with predictable increases or decreases in responding, then the antecedent is acting as a motivating operation and is altering the reinforcing effectiveness of the consequence. This conclusion is reasonable because the antecedent is not correlated with the availability or unavailability of reinforcement when the reinforcement contingency remains constant. In the current investigation, the delivery of food and praise on a VT schedule decreased escape-reinforced problem behavior, and the withdrawal of food and praise resulted in increases in problem behavior. Thus, the delivery of food (an antecedent manipulation) probably reduced problem behavior by altering the effectiveness of escape as negative reinforcement for problem behavior.

One alternative explanation of the current results is that problem behavior decreased and compliance increased (for Aaron) due to (a) adventitious reinforcement of behavior other than destructive behavior by coincidental delivery of food and praise (i.e., adventitious differential reinforcement of other behavior; DRO) or (b) adventitious reinforcement of compliance by coincidental delivery of food and praise (i.e., adventitious differential reinforcement of alternative behavior; DRA). One limitation of the current investigation is that we cannot definitively rule out such adventitious pairings because we collected data on the timing of reinforcement deliveries relative to the timing of compliance and problem behavior with only one participant (Sam). However, the fact that problem behavior decreased to zero in the first VT treatment session for all participants clearly precludes the possibility that the reductions in problem behavior were due to adventitious DRO, because the participants never displayed the behavior in that session and never contacted an adventitious delay in the VT schedule. Future investigations on this topic should collect data on the timing of reinforcer deliveries relative to the timing of compliance and problem behavior with all participants, which would permit complete contingency analyses similar to those conducted by Galbicka and Platt (1989) and Vollmer, Borrero, Van Camp, and Lalli (2001).

A second alternative interpretation of the current results is that each of the participants may have had a history of compliance being reinforced with food or praise such that one of these stimuli (or both in combination) functioned as a discriminative stimulus for increased compliance, which in turn, decreased problem behavior. This alternative explanation seems unlikely because problem behavior remained at near-zero levels throughout all VT phases for all three participants. By contrast, during the VT sessions, compliance was highly variable across participants and across sessions conducted with Sam and Mark. Therefore, it is highly unlikely that a response with a supposed history of reinforcement with food or praise (i.e., compliance) would show a lesser response to its supposed discriminative stimulus than another response (i.e., problem behavior).

One drawback of the current treatment was that clinically significant increases in compliance occurred with only one participant (Aaron). By contrast, Lalli et al. (1999) showed both increases in compliance and decreases in problem behavior when the therapist delivered food contingent on compliance. Thus, delivering food contingent on compliance, as opposed to noncontingently as in the current study, probably has the added clinical benefit of both reducing problem behavior and increasing compliance. Future investigators may wish to evaluate the potential effects of combining time-based delivery of food with differential positive reinforcement of compliance in a manner similar to how Marcus and Vollmer (1996) combined time-based schedules with functional communication training. The time-based schedule should help to ensure that the highly preferred stimulus is presented on a sufficiently dense schedule to produce immediate reductions in problem behavior. This may be particularly important if compliance is at zero or near-zero levels, because a differential reinforcement contingency that is never or rarely contacted would likely be ineffective at reducing problem behavior. In addition, progressively thinning the time-based schedule should increase the likelihood that the participant will display increases in compliance (to maintain high amounts of access to the high-preference stimulus).

One limitation of the current investigation is that praise was delivered concurrent with the delivery of food on the time-based schedule. Thus, it is not possible to determine whether food, praise, or the two in combination acted as an abolishing operation and lowered the participants' motivation for escape. However, it should be noted that behaviorally descriptive praise also was delivered contingent on compliance (e.g., “good job”) during both the baseline and treatment sessions. If praise was an effective reinforcer for these participants, then high levels of compliance and low levels of problem behavior should have been observed during baseline; this did not occur. Even if the delivery of praise in addition to the delivery of the food item added to the abolishing effects of food, the overall conclusions of the investigation in terms of the operant mechanism responsible for the treatment effects would not be altered much (either time-based delivery of food or time-based delivery of food plus attention acted as an abolishing operation). Nevertheless, future investigations should isolate the effects of time-based delivery of high-preference foods (separate from praise) as treatment for problem behavior reinforced by escape.

A second limitation of the study is that we did not test whether the specific food items used during the VT treatment functioned as reinforcement for destructive behavior. We typically include a tangible condition with food as the reinforcer during the functional analysis only when there is a clear history of parents or other caregivers delivering food items following problem behavior (e.g., as a means of calming the individual). Delivery of a highly preferred food item contingent on problem behavior during the functional analysis in the absence of such a history runs the risk of developing a function for problem behavior that did not exist previously (Shirley, Iwata, & Kahng, 1999). However, even if one or more of the current participants had an undetected tangible function for their problem behavior involving food or praise as the reinforcer, it would not alter the conclusions drawn from the current results substantially.

Finally, the current results suggest potential avenues for future research on the treatment of compliance and problem behavior with contingent and time-based schedules. Similar to the Lalli et al. (1999) study, Parrish, Cataldo, Kolko, Neef, and Egel (1986) investigated response covariance and found that a contingency applied to compliance that resulted in an increase in this response also decreased problem behavior, and conversely, a contingency applied to problem behavior decreased that behavior and also increased compliance. The current results suggest that the operant mechanisms responsible for the inverse effects on these two responses may be different. Parrish et al. suggested that compliance and problem behavior may be members of inverse response classes because (a) compliance is less likely to produce reinforcement when it is accompanied by problem behavior, and (b) compliance may be evoked after a period of deprivation resulting from caregivers withholding reinforcement following problem behavior.

The current results suggest that the operant mechanisms responsible for covariation between compliance and problem behavior may be somewhat independent of one another in some cases. In other words, the current results suggest that the presence of a positive reinforcer may lessen problem behavior reinforced by escape independent of whether it is delivered contingent on compliance and independent of whether compliance increases. To examine possible independent effects on problem behavior and compliance more directly, future research might compare the effects of time-based schedules on problem behavior with schedules that involve contingent reinforcement of compliance. Another possibility would be to compare the effects of reinforcement schedules that promote high rates of compliance (DRA) on negatively reinforced problem behavior with ones that promote low rates of compliance (differential reinforcement of low rates of behavior) and then vary the relative rates of reinforcement for the two schedules from one phase to the next. Such an arrangement would help to separate the effects of a competing response or inverse response class (compliance) from the rate of reinforcement delivery. Based on the current findings, one might hypothesize that denser rates of reinforcement will produce greater reductions in escape-maintained problem behavior relatively independent of the level of compliance, whereas the contingency between compliance and the positive reinforcer will determine the level of compliance.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported in part by Grant 5 R01 MH69739-02 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

REFERENCES

- Adelinis J.D, Piazza C.C, Goh H. Treatment of multiply controlled destructive behavior with food reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:97–100. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon I.G, Iwata B.A. Evaluation of a multiple-stimulus presentation format for assessing reinforcer preferences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:519–532. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon I.G, Neidert P.L, Anders B.M, Rodriguez-Catter V. Choices between positive and negative reinforcement during treatment for escape-maintained behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:521–525. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W.W, Adelinis J.D, Volkert V.M, Keeney K.M, Neidert P.L, Hovanetz A. Assessing preferences for positive and negative reinforcement during treatment of destructive behavior with functional communication training. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2005;26:153–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W.W, DeLeon I.G, Rodriguez-Catter V, Keeney K.M. Enhancing the effects of extinction on attention-maintained behavior through noncontingent delivery of attention or stimuli identified via a competing stimulus assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:239–242. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W.W, Piazza C.C, Bowman L.G, Hagopian L.P, Owens J.C, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W.W, Piazza C.C, Chiang C.L. Effects of equal and unequal reinforcer duration during functional analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:117–120. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbicka G, Platt J.R. Response-reinforcer contingency and spatially defined operants: Testing an invariance property of phi. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1989;51:145–162. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1989.51-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner A.W, Wacker D.P, Boelter E.B. An evaluation of the interaction between quality of attention and negative reinforcement with children who display escape-maintained problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:343–348. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh H.L, Iwata B.A. Behavioral persistence and variability during extinction of self-injury maintained by escape. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:173–174. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian L.P, Fisher W.W, Legacy S.M. Schedule effects of noncontingent reinforcement on attention-maintained destructive behavior in identical quadruplets. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:317–325. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley G.P, Piazza C.C, Fisher W.W, Maglieri K.A. On the effectiveness of preference of punishment and extinction components on function-based interventions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:51–65. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.6-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingvarsson E.T, Kahng S.W, Hausman N.L. Some effects of noncontingent positive reinforcement on multiply controlled problem behavior and compliance in a demand context. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41:435–440. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Dorsey M.F, Slifer K.J, Bauman K.E, Richman G.S. Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:197–209. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197. (Reprinted from Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 2, 3–20, 1982) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Duncan B.A, Zarcone J.R, Lerman D.C, Shore B.A. A sequential, test control methodology for conductional functional analysis for self- injurious behavior. Behavior Modification. 1994;18:289–306. doi: 10.1177/01454455940183003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Pace G.M, Cowdery G.E, Miltenberger R.G. What makes extinction work: An analysis of procedural form and function. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:215–240. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Pace G.M, Kalsher M.J, Cowdery G.E, Cataldo M.F. Experimental analysis and extinction of self-injurious escape behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1990;23:11–27. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1990.23-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalli J.S, Casey S, Kates K. Reducing escape behavior and increasing task completion with functional communication training, extinction, and response chaining. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:261–268. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalli J.S, Vollmer T.R, Progar P.R, Wright C, Borrero J, Daniel D, et al. Competition between positive and negative reinforcement in the treatment of escape behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:285–296. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laraway S, Snycerski S, Michael J, Poling A. Motivating operations and terms to describe them: Some further refinements. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:407–414. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman D.C, Iwata B.A. Developing a technology for the use of operant extinction in clinical settings: An examination of basic and applied research. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:345–382. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus B.A, Vollmer T.R. Effects of differential negative reinforcement on disruption and compliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:229–230. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus B.A, Vollmer T.R. Combining noncontingent reinforcement and differential reinforcement schedules as treatment for aberrant behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:43–51. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace G.M, Ivancic M.T, Jefferson G. Stimulus fading as treatment for obscenity in a brain-injured adult. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:301–305. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish J.M, Cataldo M.F, Kolko D.J, Neef N.A, Egel A.L. Experimental analysis of response covariation among compliant and inappropriate behaviors. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1986;19:241–254. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1986.19-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M.R, Piazza C.C, Martinez C.J, Volkert V.M, Santana C.M. An evaluation of two differential reinforcement procedures with escape extinction to treat food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:363–374. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C.C, Fisher W.W, Hanley G.P, LeBlanc L.A, Worsdell A.S, Lindauer S.E, Keeney K.M. Treatment of pica through multiple analyses of its reinforcing functions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:165–189. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C.C, Fisher W.W, Hanley G.P, Remick M.L, Contrucci S.A, Aitken T. The use of positive and negative reinforcement in the treatment of escape-maintained problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:279–298. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C.C, Patel M.R, Gulotta C.S, Sevin B.M, Layer S.A. On the relative contributions of positive reinforcement and escape extinction in the treatment of food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:309–324. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley M.J, Iwata B.A, Kahng S. False-positive maintenance of self-injurious behavior by access to tangible reinforcers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:201–204. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.G, Iwata B.A, Goh H, Shore B.A. Analysis of establishing operations for self-injury maintained by escape. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:515–535. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer T.R, Borrero J.C, Van Camp C, Lalli J.S. Identifying possible contingencies during descriptive analyses of severe behavior disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:269–287. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer T.R, Marcus B.A, Ringdahl J.E. Noncontingent escape as treatment for self-injurious behavior maintained by negative reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:15–26. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]