Abstract

We previously demonstrated that elevation of astrocytic monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) levels in a doxycycline (dox)-inducible transgenic mouse model following 14 days of dox induction results in several neuropathologic features similar to those observed in the Parkinsonian midbrain (Mallajosyula et al., 2008). These include a specific, selective and progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra (SN), selective decreases in mitochondrial complex I (CI) activity and increased oxidative stress. Here, we report that the temporal sequence of events following MAO-B elevation initially involves increased oxidative stress followed by CI inhibition and finally neurodegeneration. Furthermore, dox removal (DR) at days 3 and 5 of MAO-B induction was sufficient to arrest further increases in oxidative stress as well as subsequent neurodegenerative events. In order to assess the contribution of MAO-B-induced oxidative stress to later events, we compared the impact of DR which reverses the MAO-B increase with treatment of animals with the lipophilic antioxidant compound EUK-189. EUK-189 was found to be as effective as DR in halting downstream CI inhibition and also significantly attenuated SN DA cell loss as a result of astrocytic MAO-B induction. This suggests that MAO-B-mediated ROS contributes to neuropathology associated with this model and that antioxidant treatment can arrest further progression of dopaminergic cell death. This has implications for early intervention therapies.

Keywords: Monoamine oxidase B, Parkinson's disease, Substantia nigra, Mitochondrial complex I, Tyrosine hydroxylase, Reactive oxygen species

Introduction

Monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) is found in the brain primarily in non-neuronal cells such as astrocytes and radial glia [20,40,41]. Age-related increases in its levels have been suggested to play a role in neurodegeneration associated with PD [9,10,20,31,33]. This is believed to be as a consequence of increased oxidative stress; substrate oxidation by the enzyme is accompanied stoichiometrically by the reduction of oxygen to H2O2 [5,39]. We previously demonstrated that elevations in astrocytic MAO-B levels in an inducible transgenic mouse model results in a selective loss of dopaminergic SN neurons and that severity of this loss was age-dependent [22]. Cell loss was accompanied by increased oxidative stress and selective inhibition of mitochondrial CI activity, all key features of human Parkinson's disease (PD). Reversing MAO-B induction after 14 days was not sufficient to reverse any of the observed effects when examined 2 weeks later. However, what is not clear from our earlier studies is whether reversing the MAO-B increase at earlier time points would be sufficient to prevent subsequent events or the mechanisms involved. We set out in this current set of studies to investigate the exact timing of events and whether reversal of MAO-B induction at earlier time points was capable of halting or delaying the observed neuropathological progression.

Materials and methods

Induction of astrocytic MAO-B levels via dox feeding and impact of dox removal

Dox-inducible astrocytic MAO-B expressing transgenics were generated in the C57Bl/6 background as previously described [22]. Mice were housed according to standard animal care protocols, fed ad libitum, kept on a 12-h light/dark cycle, and maintained in a pathogen-free environment in the Buck Institute Vivarium. Astroglial-specific transgene expression was induced by feeding adult (3–4months old) males doxycycline at 0.5 g/kg/day provided in pre-mixed Purina chow (Research Diets) for the designated time periods (1, 3, 5, 7, 10, or 14 days) prior to sacrifice for various analyses n = 6 animals per time point; a subset of 6 animals at time points 3and 5were taken for dox removal studies and sacrificed at day 14 following dox removal at these earlier time points. EUK-189 was given at a dosage of 30 mg/kg/day subcutaneously (n = 6 per group) daily starting at either days 0 or 3 of initiation of dox treatment through day 14.

Analyses of ROS levels in immuno-isolated striatal dopaminergic synaptosomes

Three hours prior to sacrifice, mice were injected in the tail vein with ~200 µg DCFDA (Calbiochem) diluted in PBS [1]. Dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic synaptosomes were subsequently isolated from striatal tissues using a modified immuno-magnetic protocol as previously described [3,22]. DCF fluorescence was measured in the synaptosomal samples in the absence or presence of 1 mg/ml catalase as previously described [22]. Relative fluorescence was normalized to synaptosomal protein quantified using Bio-Rad reagent.

Analyses of CI activity levels in immuno-isolated striatal dopaminergic synaptosomes

Complex I activities were assayed in isolated dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic synaptosomal fractions as rotenone-sensitive NADH dehydrogenase activity by measuring DCPIP (2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol) reduction in synaptosomal extracts following addition of 200 µM NADH, 200 µM decylubiquinone, 2 mM KCN, and 0.002% DCPIP in the presence and absence of 2 µM rotenone [38]. Values were normalized/protein using BioRad reagent.

Neurodegeneration as assessed by silver staining

Neurodegeneration in dopaminergic SN cells was visualized by silver staining (FD Neurotechnologies, Ellicott City, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions using proprietary compounds after immunostaining the sections with antibody against tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, Chemicon, 1:500) visualized with Vector Blue alkaline phosphatase (Vector Laboratories). Quantitation was performed via double-blind analyses of TH+ SN neurons containing punctate silver staining and reported via a relative scale.

SN TH+ cell counts

Stereological cell counts were performed on immunostained brain sections from brains harvested 2 weeks after induction using antibody against TH (Chemicon, 1:500) followed by biotin-labeled secondary antibody and development using DAB (Vector Laboratories). TH+ cells were counted stereologically throughout the SNpc [17]. Sections were cut at a 40 µm thickness, and every 4th section was counted using a grid of 100×100 µm. Dissector size used was 35×35×12 µm. Neuronal numbers were verified following NeuN+ (Chemicon, 1:100) immunostaining.

MAO-B activity

MAO-B enzyme activity was measured at days 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 14 of dox feeding in cortical homogenates via a radiometric method using 14C-β-phenylethylamine as substrate as previously described [18].

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SD for the number (n) of mice per group. Differences among the means for all experiments described were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with time or treatment as the independent factor. Newman–Keuls post hoc test was employed when differences were observed by analysis of variance testing (p<0.05).

Results

Astrocytic MAO-B increase results in subsequent increases in ROS, CI inhibition, and neurodegeneration which could be reversed via dox removal (DR) at days 3–5

Approximately 10–15% of nerve terminals in the striatum (ST) originate from SN dopaminergic neurons [25,26,29]. Enrichment of striatal dopaminergic nerve terminal (synaptosomal) populations therefore allows us to measure the impact of astrocytic MAO-B induction directly within dopaminergic nigrostriatal neurons at various time points on both ROS levels and CI activity [22]. ROS levels were measured in isolated ST dopaminergic versus nondopaminergic synaptosomes 3 h following injection of DCF into the tail vein of MAO-B transgenics following dox induction for 1, 3, 5, 7, 10 or 14 days. ROS levels was found to be elevated approximately 50% in isolated ST dopaminergic synaptosomes by day 1 following MAO-B induction and continued to rise in the first week to a final level of 7-fold control but leveled out on days 7–14 (Fig. 1) in dopaminergic synaptosomes. No increase in ROS was observed in non-dopaminergic synaptosomes. DR at days 3 and 5 was able to halt or delay any further increases in ROS levels beyond what is observed at these time points when measured at day 14.

Fig. 1.

Elevation in MAO-B results in increased ROS within dopaminergic ST synaptosomes by day 1; increase is halted by dox removal and EUK treatment. ROS levels were estimated in striatal dopaminergic (DA) and non-dopaminergic (NDA) synaptosomes 3 h following tail vein injection of DCFDA at days 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10 and 14 of dox induction and following dox removal at days 3 and 5; animals were sacrificed for analysis on day 14. EUK189 (30 mg/kg) was administered to animals on days 0 and 3. DCF fluorescence was examined at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and emission of 512 nm. Data reported are normalized to µg synaptosomal protein. N = 6 animals per group; F value = 2263, df value = 65 (Prism software). p values: *p<0.05, **p<0.001, versus day 0 dox, 0.05≥#p versus same day no dox removal (3DR vs. 3 and 5DR vs. 5) where no significant difference was observed, ++p<0.001 vs. 14 day dox.

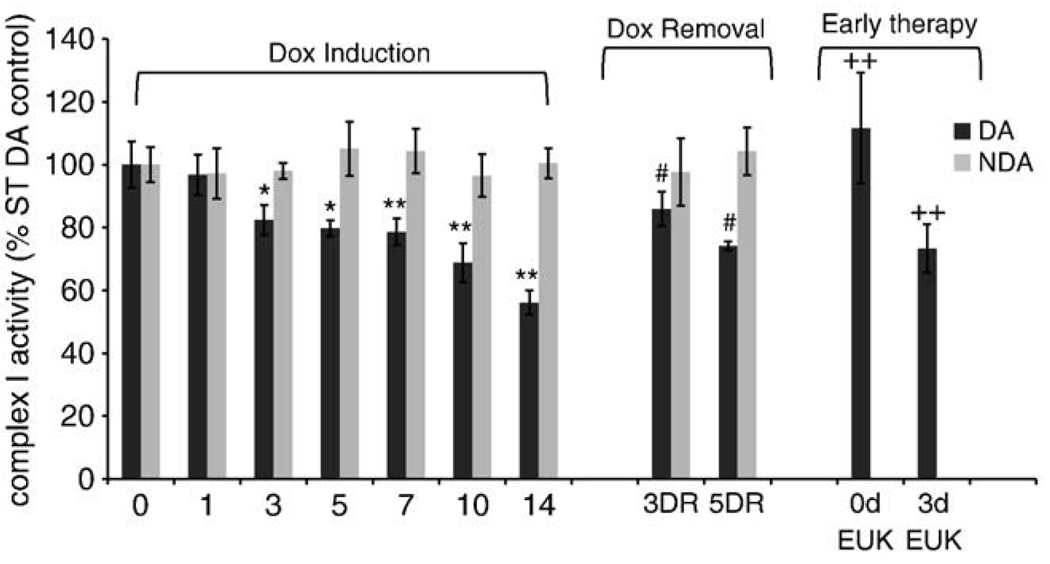

We next assessed the time course of rotenone-inhibitable CI activity in ST dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic synaptosomes following MAO-B induction (Fig. 2); our previous study demonstrated selective inhibition of enzyme activity following 2 weeks of MAO-B induction [22]. Here we observed loss of CI activity by day 3 of MAO-B induction (~18% decrease); this activity was found to be further reduced on days 5, 7, 10, and 14 respectively following dox induction (to 44% by day 14). No significant change was noted in CI activity in the non-dopaminergic samples. We found that reversal of MAOB induction by DR at 3rd and 5th days prevented further loss of enzyme inhibition beyond what occurred at these time points when examined at day 14.

Fig. 2.

Elevation in MAO-B results in CI inhibition by day 3 which is halted or slowed by either dox removal or EUK treatment. Animals were sacrificed at days 0–14 following dox induction and complex I activity measured in isolated striatal DA versus non-DA synaptosomes. Values are expressed as mean ± SD; *p<0.01; **p<0.001 compared to day 0 dox. For DR studies, dox was removed from the feed at days 3 and 5 followed by sacrifice at day 14. #p>0.05 compare with dox-induced (3DR vs. 3, 5DR vs. 5) no significant difference was observed among these groups. EUK189 treatment was initiated at days 0 and 3 and continued to day 14 followed by sacrifice; F value = 26.92, df value = 65 (Prism software). p values: ++p<0.001 compared to 14 day dox induction. N = 6 animals per group, data represents pooled striata from 2 animals.

Stereological SN TH cell counts were performed at days 3, 5, 7, 10 and 14 following dox induction in the absence or presence of dox removal at days 3 and 5 (Fig. 3). Dox removal at these time points attenuated any further loss of SN TH+ cell numbers beyond what was normally observed at these time points when examined at day 14. These results were verified by silver staining in TH+-immunostained cells; a significant increase in black punctae was noted by day 5 following MAO-B induction and to increase through day 14 (data not shown). DR at days 3 and 5 was found to halt further appearance of signs of neurodegeneration.

Fig. 3.

Elevation in MAO-B results in neurodegeneration by days 5–7 which is delayed by dox removal and early EUK treatment. Total numbers of TH+ SN neurons as assessed by sterological cell counts. Data are expressed as total SN TH+ cell numbers per animal; as calculated by prism software F value is 20.17 and df value is 39 followed p values **p<0.01, ***p< .001 compared to day 0 dox, #p>0.05 compared to same day no dox removal (3DR vs. 3 and 5DR vs. 5) no change was observed in total dopaminergic cell counts between these groups, ++p<0.001 vs. 14 day dox.

EUK treatment halts progressive losses in CI activity and nigrostriatal neurodegeneration even when administered up to day 3 following MAO-B induction

The fact that dox removal at day 3 was able to halt further MAO-B increases in ROS levels as well as subsequent neuropathological events including loss of CI activity and nigrostriatal neurodegeneration suggests that oxidative stress may contribute to these later events. In order to assess this possibility, we compared our previous DR results with administration of the lipophilic antioxidant compound EUK-189 at this same time point. Based on earlier published data [22], EUK treatment has been shown to attenuate MAO-B-mediated ROS production and subsequent neurodegeneration. In this current study, at the time points during the first week when ROS levels are found increased, EUK treatment was found to attenuate both CI inhibition and neurodegeneration suggesting that ROS is involved in both of these processes. Administration of EUK-189 throughout the course of dox-induced MAO-B elevation was found completely attenuate CI activity decrease and to attenuate SN DA cell loss (Figs. 2 and 3). Administration of the drug at day 3 was also found to attenuate further losses in CI activity almost (but not quite) as completely as DR. It was in addition nearly as affective in attenuating SN DA cell loss as treatment at day 0.

MAO-B activity time course

In order to confirm the impact of dox-induction of MAO-B expression on enzyme activity, we performed an activity time course from days 0 to 14 (Fig. 4). While as expected there was an initial increase in MAO-B activity at day 1 coinciding with the noted increase in ROS at this time point, surprisingly we noted a transient decrease in enzyme activity on days 3–7 although by day 14 levels had reached 2-fold that of controls as we have previously reported in these mice [22].

Fig. 4.

MAO-B activity at various time points of dox induction. MAOB activity was estimated on days 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10 and 14 of dox induction and reported as cpm/µg protein. N = 3 animals per group; F value = 293.3, df value = 20. ***p<0.001, day 0 vs. days 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 14.

Discussion

Increased brain MAO-B levels have been hypothesized to play a role in neuropathies associated with PD [4,5,15,23,27,42]. It was recently reported that rasagaline (Azilect), a selective irreversible inhibitor of MAO-B, resulted in a delay in disease development in patients who initiated drug treatment at the earlier stages which is consistent with a neuroprotective effect (although this is confounded by the mild improvements and questions about differences with drug dosage). It is not clear from these studies however whether “neuroprotection” occurs as a consequence of MAO-B inhibition alone or due to other actions of the drug. In order to directly address the possible role of age- and disease-related elevations in MAO-B in disease initiation and/or progression and to test whether pre-symptomatic MAO-B inhibition is protective, we created an transgenic mouse model in which MAO-B can be inducibly elevated in astrocytes in adult animals. We reported that elevations in astrocytic MAO-B levels in this model resulted in selective age-related loss of dopaminergic SN neurons [16,22]. Observed cell loss was accompanied by increased oxidative stress and selective decreases in mitochondrial complex I activity in these cells, key pathological hallmarks of the human PD. These events were prevented by co-treatment with the MAO-B inhibitor deprenyl. These data suggest that astrocytic MAO-B elevation can result in selective inhibition of CI activity and accompanying dopaminergic SN neurodegeneration but not the mechanism(s) involved. It also does not address whether the affects of MAO-B can be slowed or halted or at what time point. In this current study, we report that the temporal sequence of events following MAO-B elevation involves increased oxidative stress followed by CI inhibition and finally neurodegeneration. Furthermore, dox removal by days 3–5 halt or slow down the generation of ROS, CI inhibition and nigrostriatal neurodegeneration beyond what occurs normally at these time points. This is likely in part due to MAO-B-generated oxidative stress at day 1 as the antioxidant EUK-189 has able to attenuate further CI activity or SN DA cell losses even when given at day 3 following MAO-B induction until day 14. While EUK-mediated neuroprotection was not complete, this is likely due to other affects associated with MAO-B elevation beyond ROS-mediated CI inhibition including local microglial activation following initial dopaminergic SN cell loss which has secondary neurodegenerative affects [22]. This may explain why MAO-B inhibition alone is more protective than EUK treatment. These data suggest that reversal of the MAO-B increase and/or subsequent ROS production can halt or slow subsequent neuropathology even when upstream events including oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction are already in evidence. MAOB inhibitors and antioxidant drug therapies may therefore be beneficial in preventing disease progression if given early.

We were surprised to note a transient decrease in MAO-B activity following its initial increase on day 1. The cause for this transient decrease in activity is not clear however MAO-B mediated increases in ROS could result in elevated levels of endogenous oxidized indoles such as isatin which are known inhibitors of MAO-B activity [7]. This is currently under investigation. However by day 14, continued expression of the MAO-B transgene resulted in a 2 fold increase by day 14. These data suggest that the initial transient increase in MAO-B activity at day 1 is sufficient to result in the subsequent observed events and contribute to neurodegeneration. It may also be that the later MAO-B increases in enzyme activity at days 10–14 may also contribute to cell loss in a manner independent of ROS-mediated CI inhibition such as via increased microglial activation [22].

In clinical trials which have been performed to date using MAO-B inhibitors, both deprenyl (also known as selegiline) and rasagaline were administered after symptoms were present that coincide with an already extensive loss (~60%) of nigrostriatal dopamine content. [8,12,21,28,34,36]. Administration of these agents at this advanced stage of the disease is likely to have relatively modest protective capabilities but does not address whether MAO-B inhibitors or bioavailable antioxidants given at an earlier stage might not be more effective at preventing disease progression. Our data suggest that treatment at earlier time points could perhaps halt or delay neuropathology associated with the disorder in at-risk individuals. The ability to identify individuals with increased susceptibility for the sporadic disorder based on MAO-B allele polymorphisms or platelet MAO-B activity [6,11,13,14,19,32,35,37,43] and to detect PD at early or preclinical stages using methodologies such as fluorodopa PET scanning [2,24,30] or olfactory discrimination testing may allowed this possibility to be explored.

Although neurodegeneration is more rapid than in the human condition and our model does not appear to recapitulate non-dopaminergic features of the disease, we believe these mice are a valuable tool for exploring the impact of MAO-B and subsequent oxidative stress on dopaminergic events that largely account for the cardinal motor symptoms associated with PD. Furthermore, the ability to assess the impact of reversal of MAO-B mediated events at various stages will allow us to assess reversible versus irreversible events and whether and at what stage(s) reversal of the MAO-B increase can slow or halt disease progression. These mice provide a novel model for exploring pathways involved in initiation or progression of key features associated with PD neuropathology including oxidative stress-mediated effects which may contribute to subsequent neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgments

These studies were funded by R01 NS045615 (JKA) and a grant from the National Parkinson's Foundation (JKM).

Abbreviations

- MAO-B

monoamine oxidase B

- dox

doxycycline

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- SN

substantia nigra

- CI

mitochondrial complex I

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- ST

striatum

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- DR

dox removal

- DA

dopaminergic

- NDA

non dopaminergic

References

- Andrews ZB, Horvath B, Barnstable CJ, Elsworth J, Yang L, Beal MF, Roth RH, Matthews RT, Horvath TL. Uncoupling protein-2 is critical for nigral dopamine cell survival in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:184–191. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4269-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruck A, Aalto S, Nurmi E, Vahlberg T, Bergman J, Rinne JO. Striatal subregional 6-[18F]fluoro-l-dopa uptake in early Parkinson's disease: a two-year follow-up study. Mov. Disord. 2006;21:958–963. doi: 10.1002/mds.20855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinta SJ, Kumar MJ, Hsu M, Rajagopalan S, Kaur D, Rane A, Nicholls DG, Choi J, Andersen JK. Inducible alterations of glutathione levels in adult dopaminergic midbrain neurons result in nigrostriatal degeneration. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:13997–14006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3885-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G. The pathobiology of Parkinson's disease: biochemical aspects of dopamine neuron senescence. J. Neural Transm. 1983;19 Suppl:89–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G, Farooqui R, Kesler N. Parkinson disease: a new link between monoamine oxidase and mitochondrial electron flow. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:4890–4894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa P, Checkoway H, Levy D, Smith-Weller T, Franklin GM, Swanson PD, Costa LG. Association of a polymorphism in intron 13 of the monoamine oxidase B gene with Parkinson disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1997;74:154–156. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19970418)74:2<154::aid-ajmg7>3.3.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumeyrolle-Arias M, Medvedev A, Cardona A, Tournaire MC, Glover V. Endogenous oxidized indoles share inhibitory potency against [3H]isatin binding in rat brain. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 2007;72:29–34. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-73574-9_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson's disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 5):2283–2301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CJ, Wiberg A, Oreland L, Marcusson J, Winblad B. The effect of age on the activity and molecular properties of human brain monoamine oxidase. J. Neural Transm. 1980;49:1–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01249185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach M, Youdim MB, Riederer P. Pharmacology of selegiline. Neurology. 1996;47:S137–S145. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.6_suppl_3.137s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudreau JL, Maraganore DM, Farrer MJ, Lesnick TG, Singleton AB, Bower JH, Hardy JA, Rocca WA. Case-control study of dopamine transporter-1, monoamine oxidase-B, and catechol-O-methyl transferase polymorphisms in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2002;17:1305–1311. doi: 10.1002/mds.10268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser RA, Olanow CW. Orobuccal dyskinesia associated with trihexyphenidyl therapy in a patient with Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 1993;8:512–514. doi: 10.1002/mds.870080417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernan MA, Checkoway H, O'Brien R, Costa-Mallen P, De Vivo I, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Kelsey KT, Ascherio A. MAOB intron 13 and COMT codon 158 polymorphisms, cigarette smoking, and the risk of PD. Neurology. 2002;58:1381–1387. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.9.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho SL, Kapadi AL, Ramsden DB, Williams AC. An allelic association study of monoamine oxidase B in Parkinson's disease. Ann. Neurol. 1995;37:403–405. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin I, Finnegan KT, DeLanney LE, Di Monte D, Langston JW. The relationships between aging, monoamine oxidase, striatal dopamine and the effects of MPTP in C57BL/6 mice: a critical reassessment. Brain Res. 1992;572:224–231. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90473-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalfon L, Youdim MB, Mandel SA. Green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate promotes the rapid protein kinase C- and proteasome-mediated degradation of Bad: implications for neuroprotection. J. Neurochem. 2007;100:992–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur D, Yantiri F, Rajagopalan S, Kumar J, Mo JQ, Boonplueang R, Viswanath V, Jacobs R, Yang L, Beal MF, DiMonte D, Volitaskis I, Ellerby L, Cherny RA, Bush AI, Andersen JK. Genetic or pharmacological iron chelation prevents MPTP-induced neurotoxicity in vivo: a novel therapy for Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2003;37:899–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar MJ, Nicholls DG, Andersen JK. Oxidative alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase inhibition via subtle elevations in monoamine oxidase B levels results in loss of spare respiratory capacity: implications for Parkinson's disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:46432–46439. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth JH, Kurth MC, Poduslo SE, Schwankhaus JD. Association of a monoamine oxidase B allele with Parkinson's disease. Ann. Neurol. 1993;33:368–372. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt P, Pintar JE, Breakefield XO. Immunocytochemical demonstration of monoamine oxidase B in brain astrocytes and serotonergic neurons. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1982;79:6385–6389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.20.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeWitt PA. Clinical trials of neuroprotection in Parkinson's disease: long-term selegiline and alpha-tocopherol treatment. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 1994;43:171–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallajosyula JK, Kaur D, Chinta SJ, Rajagopalan S, Rane A, Nicholls DG, Di Monte DA, Macarthur H, Andersen JK. MAO-B elevation in mouse brain astrocytes results in Parkinson's pathology. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1616. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel S, Amit T, Reznichenko L, Weinreb O, Youdim MB. Green tea catechins as brain-permeable, natural iron chelators-antioxidants for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2006;50:229–234. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanni C, Fanti S, Rubello D. 18F-DOPA PET and PET/CT. J. Nucl. Med. 2007;48:1577–1579. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.041947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirenberg MJ, Chan J, Liu Y, Edwards RH, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural localization of the vesicular monoamine transporter-2 in midbrain dopaminergic neurons: potential sites for somatodendritic storage and release of dopamine. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:4135–4145. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04135.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirenberg MJ, Vaughan RA, Uhl GR, Kuhar MJ, Pickel VM. The dopamine transporter is localized to dendritic and axonal plasma membranes of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:436–447. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00436.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olanow CW. A rationale for monoamine oxidase inhibition as neuroprotective therapy for Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 1993;8 Suppl 1:S1–S7. doi: 10.1002/mds.870080503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson's Study group. Mortality in DATATOP: a multicenter trial in early Parkinson's disease. Parkinson Study Group. Ann. Neurol. 1998;43:318–325. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickel VM, Nirenberg MJ, Milner TA. Ultrastructural view of central catecholaminergic transmission: immunocytochemical localization of synthesizing enzymes, transporters and receptors. J. Neurocytol. 1996;25:843–856. doi: 10.1007/BF02284846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racette BA, Good L, Antenor JA, McGee-Minnich L, Moerlein SM, Videen TO, Perlmutter JS. [18F]FDOPA PET as an endophenotype for Parkinson's disease linkage studies. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2006;141B:245–249. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riederer P, Konradi C, Schay V, Kienzl E, Birkmayer G, Danielczyk W, Sofic E, Youdim MB. Localization of MAO-A and MAO-B in human brain: a step in understanding the therapeutic action of L-deprenyl. Adv. Neurol. 1987;45:111–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders-Pullman R. Estrogens and Parkinson disease: neuroprotective, symptomatic, neither, or both? Endocr. 2003;21:81–87. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:21:1:81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saura J, Richards JG, Mahy N. Age-related changes on MAO in Bl/C57 mouse tissues: a quantitative radioautographic study. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 1994;41:89–94. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9324-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider E. DATATOP-study: significance of its results in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 1995;46:391–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao M, Liu Z, Tao E, Chen B. Polymorphism of MAO-B gene and NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase gene in Parkinson's disease. Zhonghua Yi. Xue.Yi. Chuan Xue. Za Zhi. 2001;18:122–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoulson I. An interim report of the effect of selegiline (l-deprenyl) on the progression of disability in early Parkinson's disease. The Parkinson Study Group. Eur. Neurol. 1992;32 Suppl 1:46–53. doi: 10.1159/000116869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan EK, Khajavi M, Thornby JI, Nagamitsu S, Jankovic J, Ashizawa T. Variability and validity of polymorphism association studies in Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 2000;55:533–538. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trounce IA, Kim YL, Jun AS, Wallace DC. Assessment of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in patient muscle biopsies, lymphoblasts, and transmitochondrial cell lines. Methods Enzymol. 1996;264:484–509. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)64044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindis C, Seguelas MH, Lanier S, Parini A, Cambon C. Dopamine induces ERK activation in renal epithelial cells through H2O2 produced by monoamine oxidase. Kidney Int. 2001;59:76–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westlund KN, Denney RM, Kochersperger LM, Rose RM, Abell CW. Distinct monoamine oxidase A and B populations in primate brain. Science. 1985;230:181–183. doi: 10.1126/science.3875898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westlund KN, Denney RM, Rose RM, Abell CW. Localization of distinct monoamine oxidase A and monoamine oxidase B cell populations in human brainstem. Neuroscience. 1988;25:439–456. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youdim MB, Bakhle YS. Monoamine oxidase: isoforms and inhibitors in Parkinson's disease and depressive illness. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006;147 Suppl 1:S287–S296. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Miura Y, Shoji H, Yamada S, Matsuishi T. Platelet monoamine oxidase B and plasma beta-phenylethylamine in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2001;70:229–231. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]